Symbols by Gail Frazer (Design) and Seth Bacon (Digital Finish)

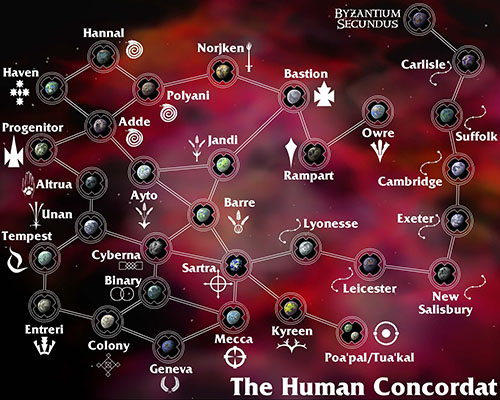

Jumpweb Map by Keith Johnson

This article was originally published in Pyramid Magazine on January 6th, 2001.

THE FALL

It was a golden age, humanity’s finest hour, and it was coming to an end. During the time of the Second Republic all of humanity had been joined into a whole across the vastness of interstellar space, but now, under the petty manipulations and power mongering of the noble families, humanity’s cohesion and greatness was pushed to its limits and then broken. The Second Republic fell.

And as the Chaos of the Fall began to spread, as darkness enveloped world after world, as the people became frightened and afraid, neighbor began to war on neighbor once more and all of human society teetered upon the edge of barbarity and obscurity. World after world sealed themselves away from neighbors who, once friendly, could now only be considered potential invaders.

These worlds were lost from Known Space – that region around Holy Terra, the birthplace of humanity, where treacherous noble families who had engineered the Fall consolidated their power. As the universe was plunged into a new Dark Age, the wonders of the Second Republic were forgotten and lost.

Over the years some of these lost worlds have regained contact with Known Space as sealed gates reopened and forgotten jumpkeys were rediscovered. There they found a power struggle between feudal lords, merchant guilds, and an orthodoxical church all struggling to impose their will upon the shattered remnants of human society. Some of these worlds have rejoined the worlds of Known Space (whether through their own will or through compulsion), while others have maintained their barbarian ways and seek to conquer the Known Worlds and seize their secrets and remaining civilization. Without exception, however, it is believed by the citizens of the Empire that the worlds of Known Space are the only significant civilization of interstellar proportion to have survived the Fall.

They are wrong.

During the aftermath of the Fall a second group of worlds found themselves isolated. As the universe fractured and the shadows spread over humanity, ten worlds found themselves alone among the stars. These ten worlds – Alhera, Cyberna, Kyreen, Unan, Mecca, Poa’pal, Tua’kal, Barre, Jandi, and Ayto – squabbled and traded and warred among each other as the memory of the Second Republic began to fade. As Known Space was sliding into a Dark Age, so, too, were these worlds. As it was for what would become the Empire, so it was for what would become known as the Human Concordat.

THE SARTRAN DOCTRINES

In the year 4110, a mere hundred years after the catastrophe of the Fall and the New Dark Age began, a new voice was heard among this small enclave of humanity. The voice belonged to a man who was known only as Sartra, and he taught a lesson of unity. He refused to recognize Alheran as different from Cybernan, or Cybernan from Jandite, or Jandite from Aytan. He called to them all as citizens of what he termed the Ten Worlds, and he reminded them that all were human. He called them brother, and in seeing him as such so they saw each other as kin. His teachings rekindled the memories of the Second Republic and a time when all humanity was composed of a single, glorious whole. He gave the people of the Ten Worlds a new identity, a common identity. He brought them together and bound them to a common purpose.

His words inspired many, both high and low, but the most important of his converts was Duke Daneel, the eldest member of House Britannia. House Britannia was of minor importance before the Fall, but had managed to secure sole sovereignty over the planet of Alhera. By the time of Sartra, Alhera had risen to be the brightest star of the Ten Worlds and House Britannia’s power had grown great indeed. But Daneel was a wise and compassionate man, and when he heard the words of Sartra he sought out this man and gained his friendship.

His words inspired many, both high and low, but the most important of his converts was Duke Daneel, the eldest member of House Britannia. House Britannia was of minor importance before the Fall, but had managed to secure sole sovereignty over the planet of Alhera. By the time of Sartra, Alhera had risen to be the brightest star of the Ten Worlds and House Britannia’s power had grown great indeed. But Daneel was a wise and compassionate man, and when he heard the words of Sartra he sought out this man and gained his friendship.

Of perhaps only slightly less importance than Duke Daneel was General Anton Baghera, the feudal warlord who had seized control of the world of Cyberna twenty years earlier and now ruled it with an iron grip. He, too, became Sartra’s friend, and these three unlikely allies joined upon an even more unlikely mission – the establishment of an interstellar government which was, in many ways, even more liberal than that which had ruled over the Second Republic. In the year 4125 General Baghera and the nobles of House Britannia both relinquished their power, and the worlds of Alhera and Cyberna both became the first members of the newly formed Human Concordat, with Sartra elected as its first president.

Over the next decade the remaining eight members of Sartra’s Ten Worlds joined the Concordat, one by one, with Mecca – ruled over by the suspicious Orthodox Church – joining last in 4135. Although the Concordat, under the careful guidance of President Sartra, never attempted any military or economic coercion of the other worlds, still blood was shed. Freedom fighters on many worlds threw down what they saw as oppressive governments, while freedom fighters on other worlds attempted to prevent their world from “surrendering” to the Concordat (of particular note is the Order for Aytan Freedom which nearly succeeded in sealing Ayto’s jumpgate in order to prevent their world from joining the new government).

Shortly after Mecca joined the Concordat Sartra’s second term of office as President came to an end and he retired from public life. He lived a life of seclusion for another ten years before disappearing entirely in the year 4145. Shortly following his disappearance, and assumed death, a collected book of his teachings – entitled the Sartran Doctrines – appeared. This book, still considered the greatest philosophical and political teachings ever constructed, has proved to be one of the most important historical documents to the Human Concordat, second only to the Constitution which also bears Sartra’s hand.

THE HUMAN CONCORDAT

It has been over 850 years since Sartra’s death. During that time the Concordat has slowly grown to be the society which Sartra imagined not only as an ideal, but as a reality. They have become a liberal and peace-loving people, worked hard to regain the technological knowledge lost during the Fall, and dedicated themselves to the principles of liberty and equality which Sartra set down in the Doctrines. To a large degree they have succeeded.

Perhaps one of the highest things that the Concordat values is the preservation of knowledge. Through the Doctrines the memories of the Fall are still kept fresh, and all of Concordat society dreads such a repetition. Knowledge, they know, is the most precious of all commodities – and all too easily lost. They have worked hard to regain what was lost during one hundred years of barbarity, and have largely succeeded – propelling their understanding of the universe back to a place which is, in some ways, stronger than the Second Republic, while still being deficient in others.

The Concordat has also taken steps to recompense the alien species which have been trodden under humanity’s foot over the millenia – even going so far as to restore homeworlds where that has been possible. These initiatives meant that when the Concordat again made contact with the Vau, their relationship with them was much easier than it had been in the past. Although it is perhaps not peace, it is an understanding.

But the Concordat has not contented itself with civil rights merely for the disenfranchised within its borders, it has pushed for a society which is in all ways possessed of more liberty and greater hope. These advances, naturally, have had their price for some: The nobles were disenfranchised under the rule of Sartra, and now they are nothing but fading memories. The Church, unable to politically force one view of itself upon the populace, has found itself splintered time and again by divisive sects of belief. Although it is still technically true that nearly 75% of the population believes in the Pancreator, many of these are those whose place in the church has lapsed along with their conviction.

In truth, though, perhaps the greatest accomplishment of the Concordat is not tangible at all – but rather the essence of the society they have unconsciously constructed. Where Sartra found a set of fractured and disparate worlds there is now one society, which has as its identity not separate cultures, but all humanity. Where once humanity was divided, it has been made whole. As, over the years, other lost worlds have made contact with the Concordat and joined this society, it has become apparent that the greatest gifts which have been offered are these: Unity, Peace, and Hope.

CONCORDAT AND EMPIRE

The year is now 5000 A.D. In Known Space five years have passed since the coronation of Emperor Alexius, whose brave new reforms and attempts to rekindle an exploratory spirit in his people have just begun to have some long-term effect. In the midst of this growing renaissance in the Empire, a jumpgate between one of the outer worlds of the Concordat and Byzantium Secundus reopens.

The first tentative contact between these two societies has been mutually positive. Emperor Alexius is overjoyed to have regained contact with so large a segment of lost humanity, while the Concordat is overjoyed in the discovery that they have not been alone in maintaining interstellar civilization. But these two societies are polar opposites of each other – diametrically positioned on the political, social, and religious spectrums. Although for now goodwill prevails, can it not be said that conflict is inevitable? And if so… what then?

Given the deep connections between the two plays, it would be logical to assume that either

Given the deep connections between the two plays, it would be logical to assume that either

1. Species that simply prefer living underground (either because they fear the sun like the drow or because they love the dark like the dwarves).

1. Species that simply prefer living underground (either because they fear the sun like the drow or because they love the dark like the dwarves).