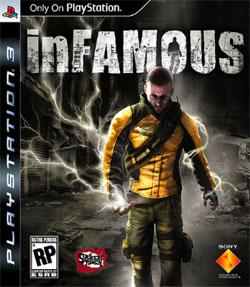

After a procrastination of nearly epic proportions, I finally subscribed to GameFly last week. The GameFly queue system is not nearly as elegant as Netflix (since it seems to basically amount to a crap-shoot no matter what priority you actually give the games in your queue), but the result was that Infamous materialized in my mailbox a couple of days ago.

After a procrastination of nearly epic proportions, I finally subscribed to GameFly last week. The GameFly queue system is not nearly as elegant as Netflix (since it seems to basically amount to a crap-shoot no matter what priority you actually give the games in your queue), but the result was that Infamous materialized in my mailbox a couple of days ago.

Infamous is a sandbox game of superpowers in which you have the choice to either be a superhero or a supervillain. My initial impression could be summed up as something along the lines of Grand Theft Auto + Knights of the Old Republic + Star Wars: The Force Unleashed. (The inclusion of two Star Wars games might seem excessive: But The Force Unleashed didn’t have KOTOR’s elegant light-vs-dark story arcs, while KOTOR didn’t have The Force Unleashed’s Force lightning powers.)

Where Infamous succeeds is the basic gameplay: Parkour-inspired climbing and leaping combined with an effective and interesting mix of electrical superpowers. Where it fails is the writing, which eventually turns the interesting gameplay into a mind-numbingly endless repetition of “been there, done that”. (In a fit of dark irony, the game even has an achievement trophy called “Oh, So You’ve Done This Before”.)

What I find particularly notable about these failures is the ultimately trivial amount of effort it would have taken to vastly improve the quality of the game: Hundreds of thousands of hours and millions of dollars were spent to make this game a reality, but it would have taken only a few hours from a dedicated writer and a fraction of a percentage of that budget to take a disposable trifle and raise it to the level of the sublime.

Which is what prompted this Rewrite essay. It’s obviously not going to do all the work, but it is going to sketch out the handful of simple fixes that Infamous practically cries out for. (Be warned: There will be SPOILERS.)

FAULT 1: THE SANDBOX

The primary shortcoming in Infamous lies in the design of its sandbox. Like most modern sandboxing games, Infamous draws its basic structure from the tradition of Grand Theft Auto 3. And like most modern sandboxing games, Infamous fails to learn some important lessons from Grand Theft Auto 3 (while also failing to capitalize on the opportunity to improve the format in key ways).

To simplify things, there are four types of content in Grand Theft Auto 3:

(1) The main storyline. (A sequential series of missions designed to be completed one after the other while telling the story of the game.)

(2) Designed side-quests. (Specifically designed mini-missions or mini-quest lines that the player could choose to either play or ignore.)

(3) Procedurally generated missions. (Missions created on-demand by the game engine and, thus, creating a bottom-less supply of semi-variable gameplay. Examples include the taxi- and ambulance-driving missions.)

(4) Self-guided play. (Because the game world responded dynamically to player activity, the player could engage in rewarding self-guided play by, basically, seeing “what happens when I do this”. Grand Theft Auto 3 didn’t have much in the way of dynamic world response, but even something as simple as “police chase you if your wanted rating is high enough” resulted in an endless variety of entertaining car chases.)

The first flaw in the Infamous sandbox is the limited nature of the self-guided play: In general, this play is limited to “there are bad guys roaming the streets, fight them” — basically the random encounters of an old school Final Fantasy game. (Surprisingly, despite the parkour-style climbing, there is little or no attention given to providing massive climbing vistas like those to be found in Assassin’s Creed.) Even worse, the primary sub-quests are designed to make city neighborhoods “safe” so that enemies no longer appear — which means that you’re literally removing content from the game as you play the game.

The second flaw is the complete lack of procedurally-generated missions. This significantly impacts the long-term value of the game. I remember playing Grand Theft Auto 3 for years after “finishing” the game because there was always something interesting to do in Liberty City. By the time I finished Infamous, on the other hand, there was literally nothing left to do.

The most significant flaw, however, is that the designed side-quests are written as if they were procedurally-generated: They are repetitive, forgettable fluff.

Grand Theft Auto 3, on the other hand, used its side-quests to develop either plot or landmarks. The former is self-explanatory: The side-quests were interesting little one act plays standing in contrast or support to the full-length drama of the main storyline. The latter is about providing context for the city: You came to recognize Vinnie’s pizza because that’s where you delivered Leo’s drugs (or whatever, it’s been awhile since I actually played Grand Theft Auto 3). The side-quests helped to bring Liberty City to life. They filled the empty, gray building polygons with life and meaning and identity.

The side-quests of Infamous, on the other hand, have no story or life to them: An anonymous guy asks you to kill 10 bad guys. Or blow up a bus. Or kill 10 bad guys. Or kill 10 bad guys. Or kill 10 bad guys. (Did I mention they’re repetitive?)

If these were actually procedurally-generated content (as they so easily could have been), it wouldn’t be a problem. I understand the limitations of procedural content: You take a half-dozen elements, mix ’em up randomly, and that’s what you’ve got. It’s not going to fool you into thinking that an intelligent mind was authoring it.

But this isn’t procedural content: Every one of these missions has been hand-crafted and hand-placed to fill a specific and non-substitutable place in the game. But if you’re designing this content individually, why not take the effort (and the opportunity) to make it individual? And meaningful?

THE REWRITES

In Switch: How to Change Things When Change is Hard, Chip Heath encourages people to copy success instead of trying to solve problems.

In the case of Infamous, what they got right were the Dead Drop missions.

To summarize: In these missions, you hunt down satellite dishes hidden around the city. These satellite dishes were used to make dead drops by an intelligence agent, and by accessing the dishes you’re able to recover the audio logs from his investigations into the strange events plaguing Empire City. These logs, of course, reveal a prequel-like storyline over time. (Although the game allows for a non-linear collection of the satellite dishes, the information is recovered linearly. Of course, one could also take advantage of the mechanic to do truly non-linear storytelling.)

If the Dead Drop missions had been constructed like the other side-quests in the game, the complexity of their programming would not have been noticeably affected: The player would still hunt down the satellite dishes and then push a button to access them. But rather than getting a snippet of story information, the player would just receive a tally of the number of dishes they had found.

The storytelling content that makes the Dead Drop missions work, on the other hand, is almost trivial: Less than a half dozen pages of script and probably a half hour of recording time with a voice actor.

So let’s take a moment and consider how the other mission types might have been made to succeed like the Dead Drop missions.

HIDDEN PACKAGES: Using his electrical powers, Cole is able to “hack” the brain of the recently deceased to see their last memories. At various points in the game, he’s able to use this ability on his enemies, revealing the location of hidden packages they’ve secreted around the city.

In the actual game, these packages are nothing — meaningless fluff to be checked off a quest list. But how much more evocative would it have been if there was actually something worth hiding? Perhaps something that had been split up between the various packages?

The possibilites are almost endless: The schematics for the ray sphere. Records from Kessler’s surveillance of Cole. Evidence pointing to a rebel faction within the First Sons.

TRACKING THE DEAD: Similarly, Cole is able to track the ghost-like ethereal “imprints” of a person’s recent movements. (Intriguingly, this ability is always used on murderers — suggesting perhaps that the violence of their action is responsible for leaving a stronger imprint on the world around them.) This is an evocative and interesting mechanic, but it would have been nice to see some of these end with revelations more interesting than, “That’s the guy who killed Senor Red Shirt! Vengeance!”

If nothing else, having the trails lead somewhere other than “a nondescript alley with a bunch of bad guys in it” would have helped. But it wouldn’t take much effort to explain why some of these people were being particularly targeted by the bad guys.

SURVEILLANCE DEVICES: The bad guys have covered various buildings in town with dozens of surveillance devices. It’s your job to climb the building and blow up the surveillance devices.

Oddly, the game never explains why the bad guys are interested in so heavily surveilling these particular buildings. Change “blowing up” to “hacking” and you (a) effortlessly add a new power for Cole and (b) provide an easy mechanism for revealing the reason for the surveillance.

PRISONER ESCORTS: The police periodically ask us to apprehend various bad guys for “questioning”. In other cases, the bad guys have already been caught and it’s our job to escort them to the nearest police station.

Spicing this one up is pretty easy: Have the cops actually report back what they find out from this questioning. This could foreshadow various developments, point us towards new surveillance missions, and so forth.

PROCEDURAL CONTENT: This suggestion moves somewhat beyond the intended scope of this essay (since they require more than a simple rewrite within the existing strictures of the game), but it would be nice if Infamous contained some legitimate procedural content.

For example, the picture-taking missions would be perfect for procedural generation. Triage missions using our healing abilities at medical centers seems like a no-brainer. A stalker fan that pops up to ask our hero for photographs or kisses or the like (or, for the evil-siders, a would-be assassin who periodically sends robotic drones after us). “Walk me home” protection missions (or muggings for the evil-siders). Bad guys blocking roads or railroad tracks. Bomb threats that need to be defused.

THE CORE CONCEPT

The mistake made in games like Infamous and Assassin’s Creed is thinking that storytelling only needs to happen in the main storyline. I would argue that the design principle behind these GTA-like sandboxes needs to be different: Any time you’re hand-designing content (instead of procedurally generating it), that’s an opportunity to tell part of your story. And you should take it.

In general, side-quests offer you the opportunity to create storylines in addition to your primary storyline. (The successful Dead Drop missions in Infamous do this to great effect.) Some of these storylines may be short (a single quest); others may be long (dozens of missions); others will fall somewhere inbetween (three or four linked sub-quests). But the ways in which these storylines will weave together is an exercise left to the player and your game will be the richer for enabling that level of intrinsic collaboration in the creation of its narrative. The result is a unique gameplay arising out of a complex system, but the actual execution of that system is very, very simple.

Continued Tomorrow…

Most of the problems in Infamous are the result of its sandbox, but there are a couple of key problems with the main storyline as well, so let’s talk about those.

Most of the problems in Infamous are the result of its sandbox, but there are a couple of key problems with the main storyline as well, so let’s talk about those.