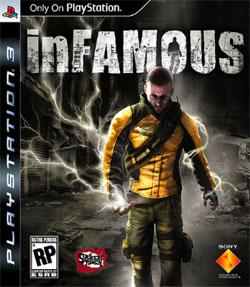

Most of the problems in Infamous are the result of its sandbox, but there are a couple of key problems with the main storyline as well, so let’s talk about those.

Most of the problems in Infamous are the result of its sandbox, but there are a couple of key problems with the main storyline as well, so let’s talk about those.

First, by its very nature, Infamous wants to give you meaningful choice: Do you want to be a supervillain or a superhero? But it runs into a problem because it also has a story to tell, goddamit.

The difficulty here is pretty easy to sum up: Content is expensive. If the game actually diverged every time it gave you a choice, the amount of content required would increase exponentially (and so would the production budget). So, instead, the game gives you the illusion of choice: No matter what you do, the ultimate result on a macro-level is the same and the next stop on the plot’s railroad remains unaltered.

Which is fine.

What you can do, though, is specifically color the events of the plot to suit the type of character the player is choosing to play. This is tricky, but it can be done. Infamous even takes a stab at it: Every so often the gameplay is shunted into a short semi-animated sequence that moves the plot forward. Some of these semi-animated sequences are swapped out depending on whether you’re a superhero or a supervillain.

The problem with Infamous is that the writers just don’t seem to have had their hearts behind the supervillain plot: No matter how villainous the character becomes, the game just can’t seem to shake the underlying themes of savior and redemption.

Fix #1: Develop a meaningful theme and arc for the supervillain side of the story. Most of the necessary pieces are tantalizingly within reach: They just need to be realized.

For example, here’s the end of the game:

Notice the complete disconnect between the end of the semi-animated sequence and the “evil epilogue”? How can you go from “when the time comes, I’ll be ready” to saying “only an idiot thinks I’m going to bother doing that”?

The fix here is simple: The narrative needs to explicitly embrace at every level the irony that Kessler’s efforts to indoctrinate Cole have had exactly the opposite result; that the unspeakable and almost incomprehensible sacrifices he made were all for naught.

More radically, it would be nice if not all of our choices were completely meaningless. (It would certainly improve the replay value of the game: After discovering how completely illusionary the choices in the game were, I didn’t bother going back to finish a replay.)

For example, you can watch the death of Trish in both the good version and the evil version. The different outcomes in this case depend on your morality rating within the game and suffers from the same incoherence as the end of the game: The fact that Trish, in her dying moments, chose to scorn you or to love you should have some sort of lasting impact on how Cole thinks of her. But it doesn’t.

In addition, the death of Trish is couched in a false decision: You can try to save her (evil choice) or you can try to save several innocent hostages (good choice). But, ultimately, the decision is meaningless: Trish is killed either way and the “decision”, like so many others in the game, is ultimately trivial and meaningless. (The game doesn’t even do a good job of giving a distinct framing to each choice.)

Supporting these variations in the death of Trish would be significant because this is a key moment in the game and its impact would be felt in many other places. But precisely because it’s a key moment in the game, a little extra depth here would go a long way towards enriching the entire experience. (And the differences, although pervasive, are cheap: A little extra time recording dialogue and a couple extra yes-no switches in the code.)

Similar changes at other moments in the game would be more isolated than the Trish divergence, and thus easier to implement.

(Tangentially: If you ever have the opportunity to write a video game, please avoid the temptation to include “you have succeeded at goal X in the gameplay, but now we’ll go to a cut-scene and reveal it was all a failure after all”. The discordant gut-punch is not effective. It is merely annoying. Particularly if you follow the example of Infamous and do it over and over and over again.)

ARCHIVED HALOSCAN COMMENTS

Justin Alexander

Keith, I think you’re looking for “Xandering the Dungeon”, which starts here: https://thealexandrian.net/wordpress/13085/roleplaying-games/xandering-the-dungeon

Hasn’t been converted to the new site yet, but I’m steadily working my way towards 2010 as time allows.

Wednesday, April 20, 2011, 3:41:37 AM

Keith Davies

Ah, excellent. That is in fact the article I was looking for. Thanks!

Friday, April 22, 2011, 12:09:04 AM

Keith Davies

ISTR seeing an article similar to this where you deconstructed a dungeon level to show that the map didn’t really offer the number or kind of choices it appeared to. IIRC you reduced it to a set of nodes, then transformed the node set to make it interesting and changed it back to a map.

Or something like that, I remember I didn’t have an opportunity to read it at the time… I think it was a few months ago, but I’m just not finding the article now.

Tuesday, April 19, 2011, 9:50:41 AM

Gravity

Great stuff – not at all that complicated but nice to see it structured in this way.

Just read Glory, the GM-screen pack scenario for Eclipse Phase, and the research phase of that scenario reminded me of this. Donät have it in front of me so cannot say for sure if it strictly followes the 3 clues rule, but it has three nodes, all pointing at each other.

Tuesday, June 01, 2010, 3:06:35 AM

Noumenon

Dry and technical my ass, that was amazingly clearly explained and the visual aid worked great.

Monday, May 31, 2010, 8:42:14 PM