Every so often I’ll indulge in what I call a “mythos delve”. This is where I’ll just dive wholeheartedly into whatever transmedia empire has transfixed my attention. A few years ago it was Star Wars. Before that Heavy Gear, The Matrix (this one was easier), Star Trek, and so forth. (This exploration of multi-faceted fictional milieus is undoubtedly part of what I find appealing about RPGs.)

Every so often I’ll indulge in what I call a “mythos delve”. This is where I’ll just dive wholeheartedly into whatever transmedia empire has transfixed my attention. A few years ago it was Star Wars. Before that Heavy Gear, The Matrix (this one was easier), Star Trek, and so forth. (This exploration of multi-faceted fictional milieus is undoubtedly part of what I find appealing about RPGs.)

Most recently, the Halo franchise has captured my attention. A little less than a decade ago, I played both Halo: Combat Evolved and Halo 2, but then the franchise jumped to the Xbox 360 and I didn’t. That recently changed, however, and I started playing my way through the older games as prep for the newer ones. In the interim, I had also acquired the first three Halo novels from the $1 racks at Half-Price Books, which brings us here.

HALO: COMBAT EVOLVED (Bungie Studios): I’m not going to attempt anything even remotely resembling a full review of the Halo video games. (Largely because that would be redundant and pointless.) But what I will say is this: The original video game was basically Ringworld + Starship Troopers + zombies. That’s a pretty awesome premise.

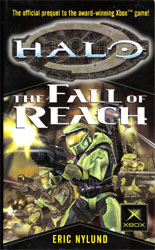

HALO – THE FALL OF REACH (Eric Nylund): I bring that up primarily because the premise for The Fall of Reach can basically be summed up as Ender’s Game + Starship Troopers.

HALO – THE FALL OF REACH (Eric Nylund): I bring that up primarily because the premise for The Fall of Reach can basically be summed up as Ender’s Game + Starship Troopers.

This proves to be an effective and entertaining variation on the themes of the original game. By shifting the underlying tropes of the story, Nylund manages to weave a tale which is true to the original without merely rehashing its content. (This can be a very fine line for tie-in fiction to tread: If you simply retread the original the result is repetitive and dull — like looking at something that’s been xeroxed too many times. If you chart your own course, on the other hand, you can end up violating the reader’s sense of how the fictional universe should work.)

Unfortunately, the training sequences lack the cleverness and unique insight which make Ender’s Game or The Hunger Games into effective young adult literature by bringing the reader along on the protagonist’s journey of discovery.The military ops are handled with more cleverness and detail, but end up being just a trifle too disjointed: They’re effective vignettes, but don’t feel like a cohesive narrative building towards some greater climax.

With that being said, if you’re a fan of Halo — or just a fan of military SF — this is a book worth checking out. It’s a fun read that kept me turning the pages.

(As a tangential note, I was amused when this book made me aware — for the very first time — that the SPARTANs are supposed to be super-fast. One of the things I had always kind of liked about Halo was the more slow / more-realistic pace it had compared to other shooters of the time. Discovering that it was actually supposed to be representing superhuman speed only served to drive home how completely inferior console controls are for first-person shooters.)

HALO – THE FLOOD (William C. Dietz): The back cover pitch for The Flood is that it will depict the events from the first video game from alternative points of view. That actually sounded really interesting to me: One of the things I really enjoyed about Halo: Combat Evolved was the implication that there was a wider, guerrilla-style war being fought across the surface of Halo as both the UNSC and Covenant forces explored this strange and alien world. Between the armed conflict, the mega-relics of the Forerunners, and the emerging threat of the Flood itself, there’s a ton of potential for developing original material while capitalizing on the video game narrative itself by showing the Master Chief’s journey (and its impact) through the eyes of others.

HALO – THE FLOOD (William C. Dietz): The back cover pitch for The Flood is that it will depict the events from the first video game from alternative points of view. That actually sounded really interesting to me: One of the things I really enjoyed about Halo: Combat Evolved was the implication that there was a wider, guerrilla-style war being fought across the surface of Halo as both the UNSC and Covenant forces explored this strange and alien world. Between the armed conflict, the mega-relics of the Forerunners, and the emerging threat of the Flood itself, there’s a ton of potential for developing original material while capitalizing on the video game narrative itself by showing the Master Chief’s journey (and its impact) through the eyes of others.

Unfortunately, the back cover pitch was lying to me. 80% of the book is just a novelization of the game (which is precisely as interesting as you would imagine a faithful novelization of a first-person shooter would be). The rest is just bland cliche starring a rotating cast of dimwitted stereotypes who have been hit over the head a few too many times with the Stupid Protagonist Hammer.

This is a book you should definitely skip.

HALO – FIRST STRIKE (Eric Nylund): One of the most fantastic and fascinating aspects of media consumption is the act of closure. In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud refers to this phenomenon as “blood in the gutters”, demonstrating how the space between one panel and the next forces the reader to perform a creative act: “Here, in the limbo of the gutter, the human imagination takes two separate images and transforms them into a single idea.” He uses the example of showing a serial killer raising an axe in one panel and then “hearing” the victim scream off-panel in the next. “I may have drawn a raised axe in this example, but I’m not the one who let it drop or decided how hard the blow, or who screamed, or why. That, dear reader, was your special crime, each of you committing it in your own style.” (The parallel to a horror film in which a victim is killed off-screen is obvious.)

HALO – FIRST STRIKE (Eric Nylund): One of the most fantastic and fascinating aspects of media consumption is the act of closure. In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud refers to this phenomenon as “blood in the gutters”, demonstrating how the space between one panel and the next forces the reader to perform a creative act: “Here, in the limbo of the gutter, the human imagination takes two separate images and transforms them into a single idea.” He uses the example of showing a serial killer raising an axe in one panel and then “hearing” the victim scream off-panel in the next. “I may have drawn a raised axe in this example, but I’m not the one who let it drop or decided how hard the blow, or who screamed, or why. That, dear reader, was your special crime, each of you committing it in your own style.” (The parallel to a horror film in which a victim is killed off-screen is obvious.)

But this phenomenon, in my opinion, is not limited to small events. And one of the dangers of tie-in fiction which attempts to “fill in the gaps” between one story and the next is that it can very easily start screwing with the closure which the viewer has already provided. This creates a natural friction and resistance from the reader as the foreign, incompatible material tries to “wipe out” their own creative response.

This is a problem which First Strike — which seeks to fill in the gap between Halo and Halo 2 — runs into headlong. And it’s severely exacerbated by some significantly inaccurate handling of continuity from Halo 2 (which may be at least partially the result of Nylund writing the book before the game was finished).

With that being said, Nylund succeeds once again at giving us an entertaining pulp romp through the Halo universe. The military ops are once again clever and varied, and Nylund also succeeds at bringing to life a cast of supporting characters that give the book depth and significance.

GRADES:

HALO – THE FALL OF REACH: C+

HALO – THE FLOOD: F

HALO – FIRST STRIKE: C-

Eric Nylund / William C. Dietz / Eric Nylund

Published: 2001 / 2003 / 2003

Publisher: Del Rey

Cover Price: $6.99 / $6.99 / $6.99

ISBN: 0345451325 / 0345459210 / 0345467817

Buy Now!