If I had a nickel for every time I’ve reviewed a D&D 5th Edition Starter Set, I’d have four nickels. Which isn’t a lot, but it’s a weird that it’s happened four times.

This particular starter set is Heroes of the Borderlands, and it’s designed to introduce new players to the D&D 2024 version of the game. I’ve previously reviewed:

If you’ve read those reviews, then you know that what I’m looking for in a starter set is a complete game. I feel strongly that no one should buy a game, take it home, and then discover that it’s just a disposable advertisement for the game they should have bought in the first place.

I also feel strongly that an effective starter set desperately needs to do a superb job of introducing new Dungeon Masters to the game. When new players buy a D&D starter set, they’re expecting it to show them how to play their first roleplaying game, and the entire experience is lynchpinned on the DM. You can’t just cross your fingers and hope they’ll figure it out on their own.

Last, but not least, the introductory adventure should (a) ideally be multiple adventures and (b) show off the unique strengths of tabletop roleplaying games. If your premiere gateway product is a railroaded nightmare or makes D&D look indistinguishable from Gloomhaven, then something has gone wrong.

(You also get bonus points if you include some sort of solo play option, so that someone opening the box on Christmas morning can immediately dive in, get a little taste of what RPGs can be like, and get excited enough to gather their friends ASAP for a proper session.)

With these principles as our guiding light, I concluded that Lost Mine of Phandelver, in the 2014 Starter Set, was quite possibly the best introductory adventure ever published for D&D (in no small part because it was actually a full-blown campaign). The rulebook in that set was also notable because it included enough source material (monsters, magic items, and so forth) that it felt like a DM could continue designing and running their own adventures even after completing the included adventure. It was hampered only by the lack of character creation rules.

The Essentials Kit, in 2019, significantly improved the rulebook by including character creation, but lacked the same robust selection of monsters and magic items. The Dragon of Icespire Peak adventure was a solid entry, but also a bit of a downgrade from Lost Mine of Phandelver. Combining the Starter Set and the Essentials Kit, on the other hand, would give you a near perfect introductory set.

In 2022, Dragons of Stormwreck Isle tried to supplant both its predecessors… and failed. Character creation was gone, the rulebook was gutted, and the adventure was mediocre at best. This was a disposable and disappointing set.

In the end, Frank Menzter’s 1983 D&D Basic Set remained the reigning champion of D&D introductory sets.

Can Heroes of the Borderlands dethrone it?

OPENING THE BOX

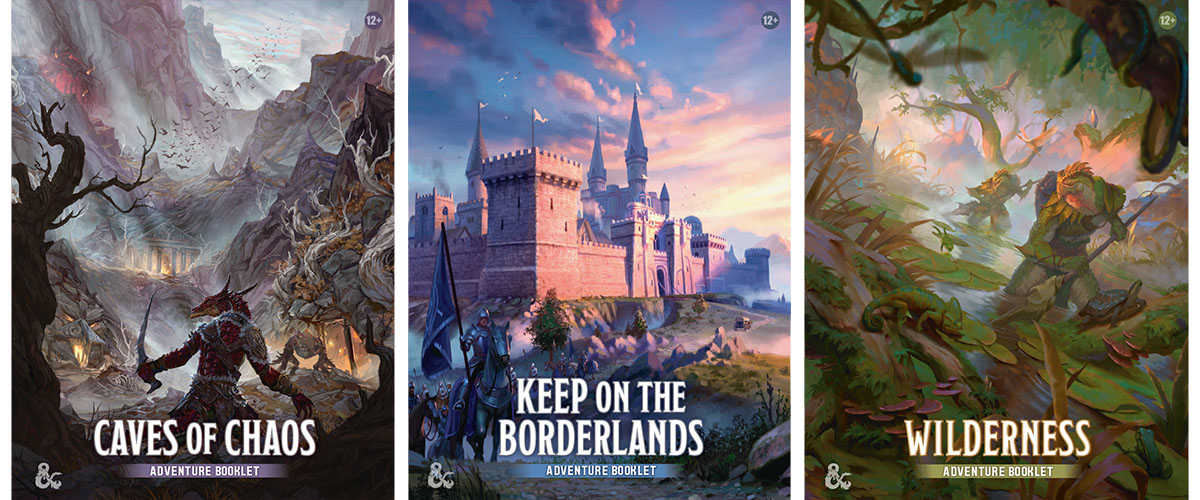

The core content of Heroes of the Borderlands is contained in the Play Guide, which serves as the rulebook, and three adventure booklets: Keep on the Borderlands, Wilderness, and Caves of Chaos.

Then you’ve got the bling:

- 9 double-sided poster maps

- 5 glossy handouts

- Pregen character boards for a Cleric, Fighter, Rogue, and Wizard (1st, 2nd, and 3rd level for each)

- Gobs and gobs of tokens (monster tokens, player tokens, terrain tokens, power tokens, hit point tokens, gem tokens, gold piece tokens)

- Background cards

- Species cards

- Magic item cards

- Spell cards

- Equipment cards

- NPC cards

- Monster cards

- A pad of Combat Tracker sheets

- A full set of dice (include 4d6 and 2d20)

It’s a lot of bling! And most of it is fully illustrated. You can definitely see where the $50 MSRP went.

RULEBOOK

In looking at the Play Guide, I think there are two key questions:

- How well does this function as an actual D&D rulebook?

- Would I want to learn D&D by reading this book?

And, obviously, these questions are obviously pretty intertwined with each other.

Well, let’s start at the beginning: The sequencing of the Play Guide is quite poor. For example, they try to describe all the Actions in the game before they explain how Turns work, which is hopelessly confusing. And they mention D20 Tests like a dozen times before telling the reader what they are. Simple procedures are needlessly cluttered up with exceptions, and the exceptions being based on rules that don’t appear until later doesn’t help.

At a more fundamental level, the Play Guide, following the lead of the 2024 Player’s Handbook, is a glossary-based rulebook. Glossary-based rulebooks kinda suck for a multitude of reasons, but they’re particularly disastrous at teaching new players how to play a game: Instead of presenting the rules as a series of instructions, they instead decouple the mechanics and expect the reader to reassemble the procedures of play. In addition to being inherently confusing, they’re also prone to making glaring mistakes, and the Play Guide inherits a bunch of mistakes from the core rulebooks without blinking an eye.

For example, in the main text the Influence action is defined as making a Charisma check to alter a creature’s attitude. In the glossary, however, the Influence action is defined as making a monster do something you want and the monster’s attitude is now a modifier on the check. If you’re an experienced DM, this is the kind of thing that just makes you sigh and shake your head. But it’s a needless booby trap for a brand new player just trying to figure out the game.

(The rules that directly contradict each other probably also distracted you from the Influence action only being usable on monsters, not NPCs. Which is just a straight-up mistake.)

You’ll also discover that core game concepts are missing from this rulebook. Proficiency bonuses, for example, have been baked into the pregen character sheets without any explanation of what they are or where they come from.

So, would I want to learn D&D from this book?

No. It’s sloppy, poorly organized (particularly for a first-time player), and incomplete.

And how well does this function as an actual D&D rulebook? Or is this just disposable trash designed to be thrown away after playing it once?

The answer here is a bit more nuanced, because the box does, for example, include a pretty diverse array of monsters, while the adventures books, as we’ll talk about in a moment, make a couple of half-hearted attempts to encourage the would-be DM to create their own adventure content. The limited character creation rules, on the other hand, have to be a pretty large ding, and the overall vibe is definitely disposable.

Most damning for me, personally, is that if you learned the game from this rulebook and then joined a group playing with the Player’s Handbook, you’d immediately be blindsided by the missing core concepts. So it’s very limited as a stand-alone experience, but also inadequate as a pathway to learning and playing the full game. It’s just a subpar manual across the board.

THE ADVENTURES

The three adventure booklets are a lot more exciting.

A single DM can take the three adventure booklets — Wilderness, Keep on the Borderlands, and Caves of Chaos — and use them as a traditional adventure or mini-campaign. But Heroes of the Borderlands also offers a more radical proposal: You can give each adventure booklet to a different player, with each one serving as the DM whenever the PCs go to the region covered by their booklet.

This is insanely cool!

First, it’s incredible to see such a big, daring concept in a product aimed at new gamers. It really challenges the engrained expectations of the RPG hobby, and even if only one table in a hundred takes the bait and begins experimenting with shared campaign worlds and other alternative structures for organizing their campaigns, that’s still a triumph.

Second, it’s such a great way to encourage more new players to try out the role of the Dungeon Master.

I’m assuming Justice Ramin Arman, the lead designer on Heroes of the Borderlands, was the one to come up with this concept and he deserves all the kudos in the world for it. This kind of thinking — and a willingness to experiment — is vital if you’re serious about growing the hobby.

As far as the adventures themselves go, there’s a goodly amount of adventure material in each one (you can expect to run this boxed set for several sessions) and, in terms of quality, it’s solid stuff.

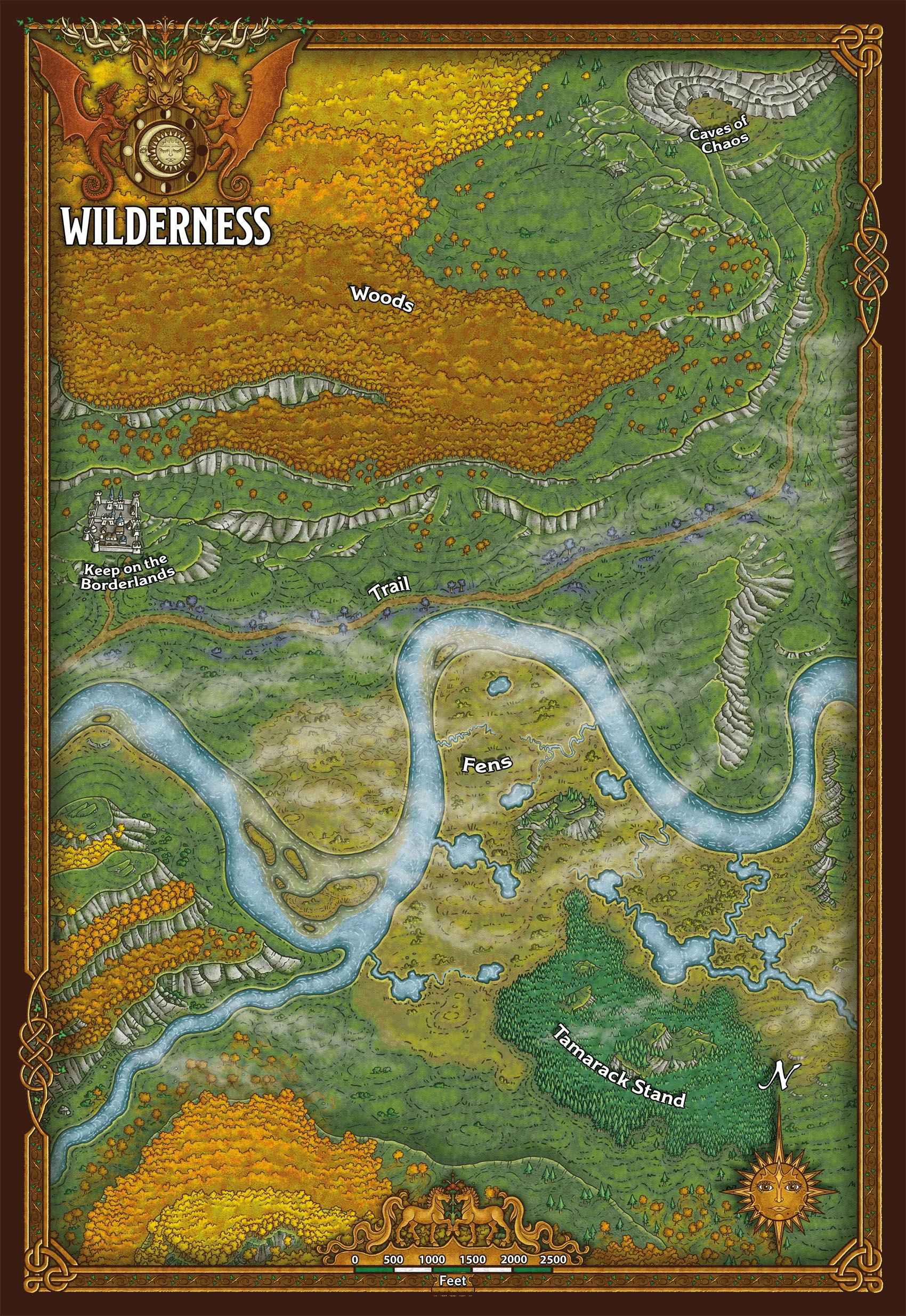

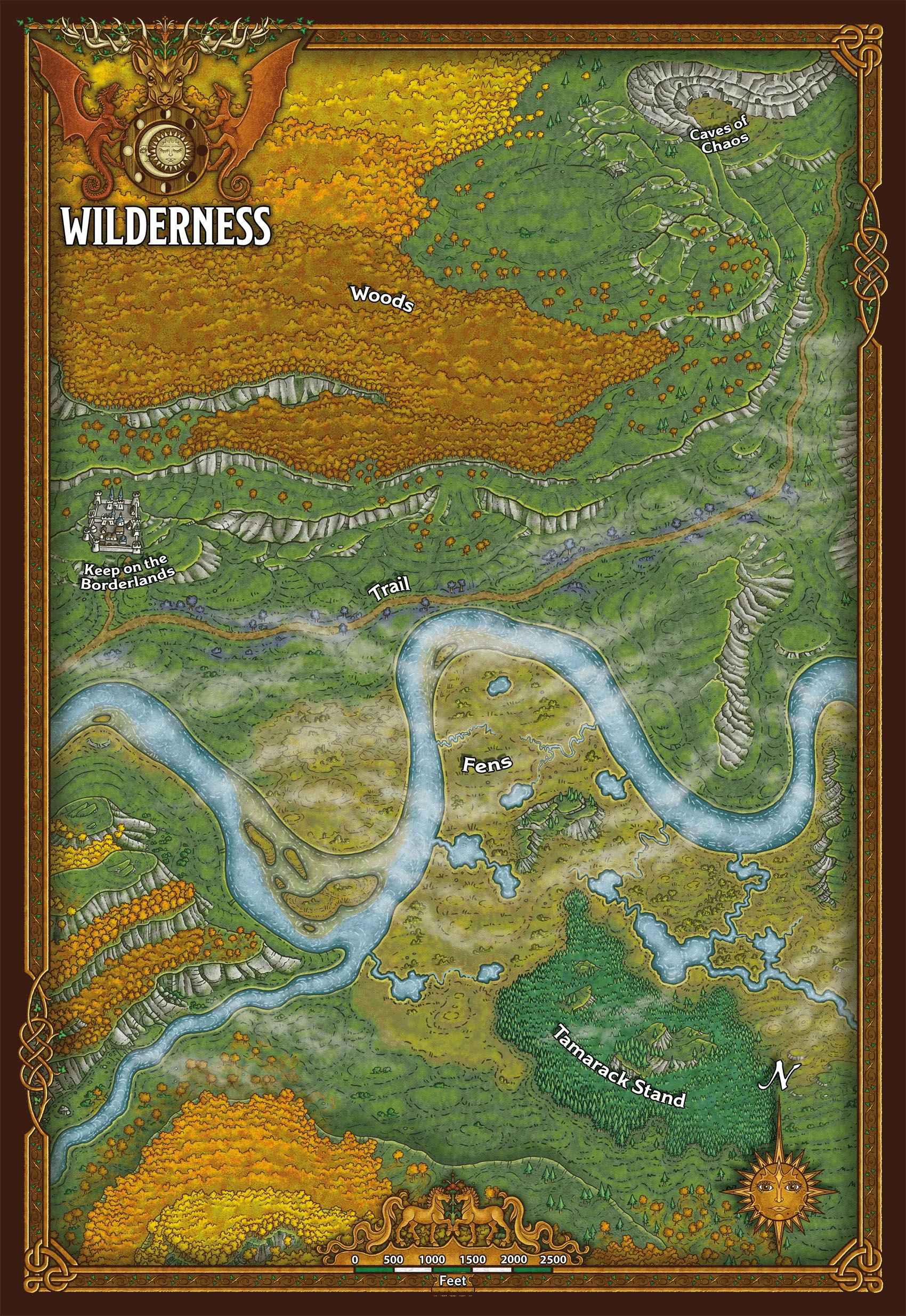

For each adventure booklet, you start by pulling out the poster map for the region and laying it on the table:

Then you simply ask the players, “Where do you want to go?”

In the case of the Wilderness, as seen above, the choices are:

- Trail

- Woods

- Tamarack Stand

- Fens

- Keep on the Borderlands

- Caves of Chaos

In this case, if the players choose to go to the Keep or the Caves of Chaos, you would swap to those adventure booklets (although possibly only after triggering one or more Trail encounters on the way there). Otherwise, you simply flip to the matching sub-region in the adventure booklet and run the encounters and/or locations detailed there.

Everything about this great. It’s a simple structure for a novice DM to grok and use. It empowers the players without overwhelming them. And the adventure material is lightly spiced with just enough clues, job offers, and the like to link the various regions together and give the players the opportunity to start pursuing specific goals.

(Although if they just keep pointing at stuff and saying, “Let’s go there now!”, that works, too.)

QUIBBLES

I do have a few quibbles with the adventures, though.

For starters, if you’re going to suggest that separate DMs could each take a separate adventure booklet and swap their PCs in and out, then you need to make sure that none of the booklets have spoilers for the other booklets. There aren’t too many of these, but they do crop up. Notably, several of these are actually phrased as tips or reminders: “Hey! Don’t forget the huge spoilers over in the Caves of Chaos!” Normally that would actually be good praxis, but here it’s fighting one intended use of the booklets.

The biggest misfires of Heroes of the Borderlands, in fact, are often places where it seems to be fighting with itself.

For example, the original Keep on the Borderlands adventure by Gary Gygax on which Heroes of the Borderland is based, is, in my opinion, a brilliant introductory adventure in large part because of the moment when the PCs step into a gorge and behold the Caves of Chaos for the first time: A dozen different cave entrances line the gorge’s walls! Which one do you want to enter?

For example, the original Keep on the Borderlands adventure by Gary Gygax on which Heroes of the Borderland is based, is, in my opinion, a brilliant introductory adventure in large part because of the moment when the PCs step into a gorge and behold the Caves of Chaos for the first time: A dozen different cave entrances line the gorge’s walls! Which one do you want to enter?

The very first action that the PCs take in the adventure is a choice. And that choice will completely reshape how the adventure plays out. It’s a moment that immediately tells a new player everything they need to know about how an RPG is supposed to work.

Initially, it seems like Heroes of the Borderlands is going to capture that same magic! “Look at this map! Just point at where you want to go!” it says. In fact, it does it three times over! Once for the Caves, again for the Wilderness, and again for the Keep!

… but then the authors immediately tell the first-time DM to take the choice away and tell the players where to go. For example, from the Caves of Chaos booklet:

Cave A functions as a tutorial with helpful sidebars. If this is your first time as the DM, encourage the players to start there.

And you can see that the intention is good: We prepped a tutorial for you!

But look at the effect it has! Instead of teaching the DM to give the players free choice, you tell them to take it away. Instead of new players having that defining moment of realizing THE CHOICE IS YOURS, their first moment in the game is instead the DM telling them what their choice will be.

First impressions matter. Wizards of the Coast has this immense privilege of being the gateway to the RPG hobby. It’s a shame that they so often prove utterly incompetent at introducing new players to the game: Not just failing to help them, but actively going out of their way to teach them the wrong things to do.

In any case, as I mentioned before, the wealth of adventure material is generally well done and supported with a plethora of poster battlemaps.

There are a few encounters that are conceptually weird: A huge forest fire that’s also surprisingly short-lived. An NPC hireling that follows video game logic (just standing around until the players click him and tell him to fight, then returning to his spawn point where the players can fetch him again). A bank that charges 10% interest per DAY. An unintentionally hilarious bit where three hobgoblins and their four goblin followers are planning to besiege a castle that has dozens of armored knights defending it.

I think my favorite alone these line is: “We’ve set up a town where you can’t buy rations because we didn’t want to include rules for that, but we’re going to frame up a ‘your hungry RIGHT NOW’ encounter where you have to immediately choose which color of pine nuts you’re going to eat, and if you choose wrong you’re going to be POISONED!”

Beyond these oddities, the material in general does suffer a bit from a lack of depth. I think the intention was to make it easier for 8-year-olds to run the game (even though the box says 12+), but I’m not sure it was the right approach. In my opinion, it’s easier to run a scenario when you understand WHY stuff is happening in the scenario. So shallow material occasionally plagued by illogical nonsense tends to leave a lot of booby traps

There are other booby traps, too, like a quest to make a map with more details than the maps given to the DM (which puts the new DM in a tough spot to start improvising the necessary details) and milestone leveling guidelines in each of the adventure booklets that, as far as I can tell, are simply incompatible with each other. (Not inconsistent. Incompatible.)

But these are, as noted, quibbles and isolated incidents. Everything here is serviceable enough. It’s mostly frustrating because it’s so close to being a lot better than the “this is OK” that it ends up being.

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

Along those same lines, there are some pretty big missed opportunities in Heroes of the Borderlands.

For example, at the end of the Wilderness book, there are eight random encounters given for each of the four sub-regions, for a total of thirty-two encounters. With just a little bit of cooking and a few hundred words, this material could have been coherently presented as an example of how to restock and expand the scenario.

Instead, it’s presented without any structure at all, and just kind of assumes that the new DM will magically know how to use random encounters.

Similarly, every cave in the Caves of Chaos book includes utterly inadequate “guidelines” for adjusting encounter difficulty. For example:

You can add monsters, such as allied Goblin Warriors, to the cave to make this scenario longer and more difficult, or you can remove some monsters to make it easier and shorter. One or two Hobgoblin Warriors might be out on a patrol elsewhere.

The new DM is given no indication of how or when or why they would want to adjust the difficulty. And if they do, for example, decide to make this lair more difficult… well, how many Goblin Warriors should they add, exactly? Two? Four? Eight? There are no encounter guidelines in this boxed set, so they’re shooting in the dark. Hope you don’t screw up and kill everybody!

Here’s another unforced error:

The characters can leave the Caves of Chaos any time they choose, provided they aren’t inside a cave or engaged in combat. If they return to a cave later, it is as they left it.

Now, I wouldn’t necessarily advise brand new DMs to run fully dynamic dungeons with enemies building fortifications, adversary rosters, restocking events between visits, and so forth. But I also wouldn’t go out of my way to tell them NOT to do that. Just because they’re not ready to take the next step, it doesn’t mean you should steer them onto the wrong path!

And if you’re going to include woefully under-documented suggestions for monsters DMs can add to the caves, why not include the idea of using those same monsters as a way of restocking the caves for future visits or brand new adventures?

BLING!

I’ve already listed all the additional bling in the Heroes of the Borderlands. The production values on this stuff is top-notch. It’s very attractive.

But I have to admit I have a bias against unnecessary knick-knacks. I understand the desire to add a lot of stuff make the cover price seem “worth it,” but I just think it’s a bad idea in an introductory product to create the perception that, for example, you “need” an equipment card for every piece of equipment the PCs are carrying.

This is particularly true when the desire to have some physical component actually gets in the way of teaching new players how to actually play D&D.

But if you like bling, it’s very nice bling.

THE VERDICT

Spreading Heroes of the Borderlands out on the table in front of me, what’s the final verdict here?

Well, I can’t recommend the rulebook to anyone. Its primary job is to teach new players and DMs how to play the game, and it’s really bad at doing that.

I’m going to give the adventures a C+. It’s solid material and lots of it, and I have to give credit for the bits where the booklets dare to dream big. (Even when they’re simultaneously cutting the legs out from under a lot of those dreams.)

Combining these things together, I’m going to give the total package a C-. (I’d probably give it a D+, but I’m going to bump it up a notch because all the bling does add tangible value.) As a Starter Set for D&D, this mostly gets the job done, and there are places where true genius shines through, like the shared DMing duties and point-at-the-map introduction to exploration and adventure. I wish they’d fully committed to some of those ideas, spent more time teaching new DMs essential skills, and spent less time sabotaging both themselves and the new players trying to learn the game.

GRADE: C-

Lead Designer: Justice Ramin Arman

Designers: Jeremy Crawford, Ron Lundeen, Christopher Perkins, Patrick Renie

Publisher: Wizards of the Coast

Cost: $49.95

Page Count: 96

BUY NOW!

ADDITIONAL READING

Keep on the Borderlands: Factions in the Dungeon