There are a bunch of different ways you could categorize dungeons (function, geography, denizens, etc.), but what I’m specifically interested in taking a look at today are structural differences that affect the fundamental design and running of the dungeon.

Most of these categories end up correlating with the size of the dungeon, and so, as you’ll see, we’ll be using size-based labels for clarity and ease of use. But don’t let that distract you from the far more important structural distinctions.

Broadly speaking, these categories also aren’t limited strictly to “dungeons” (i.e., underground warrens), but rather apply to any location-crawl scenario: Abandoned malls in zombie RPGs. Haunted mansions. Ruined Transylvanian castles. That sort of thing.

EXPEDITION-BASED PLAY

To fully appreciate the different dungeon dynamics, we first need to understand the expedition-based play which lies at the heart of the classic dungeoncrawling experience.

Here’s an excerpt from So You Want To Be a Game Master describing expedition-based play:

The basic dynamic of expedition-based play is that the party gathers a set of resources and then goes forth to pursue a goal. (In other words, they plan the expedition and then go on the expedition.) This goal might be something generic (e.g., “Get as much gold as possible”) or it might be something terribly specific (e.g., “Get revenge by slaying Orok the Minotaur”).

Some of the resources gathered for the expedition will be mechanical in nature (e.g., hit points, spell slots, etc.), but it’s likely that the PCs will also gather other resources (e.g., magic potions, rations, ammunition, etc.). Either way, the PCs will expend these resources over the course of the expedition until they run out of resources, at which point they will have to withdraw to some form of base camp at which they can replenish their resources in preparation for their next expedition.

What makes expedition-based play interesting is that the players are trying to maximize the return on their investment. In other words, they want to achieve as much as possible—to get the most gold, to clear out the maximum number of Orok’s minions, to achieve as many milestones on the way to their goal—with the resources that they have. This creates a crucible in which their strategic and tactical decisions become extremely meaningful and, therefore, extremely interesting.

To make expedition-based play really work, you want a cost associated with abandoning the current expedition and starting a new one. This is often the money spent on new supplies, but it can also be the difficulty in getting back to the point where they left off (which can be achieved in dungeon scenarios with random encounters and restocking, as discussed later in this book).

Although expedition-based play can be baked into specific roleplaying game (like D&D), it’s a more fundamental dynamic that can — and will! — transcend any particular set of game mechanics unless you take specific action to negate it. The core dynamic of “gather resources and then try to use those resources to maximum effect” is basically just how reality works. In order to prevent that from happening, special effort must be made to negate it, such as:

- Preventing resources from being beneficial.

- Handwaving the acquisition and/or depletion of resources.

- Allowing one expedition to pick up exactly where the previous expedition left off without cost.

- Creating all encounters to have a standardized difficulty/cost, so that strategic decisions become irrelevant.

- Enforcing that standardized cost (e.g., by fudging the results until the “appropriate” number of hit points have been lost).

And if you do so, of course, the playing experience of your dungeons will be greatly flattened. It’s not just that this will strip the strategic element of play, it’s that stripping the strategic element of play will also greatly reduce the variety and stakes of your tactical encounters.

DUNGEON TYPES

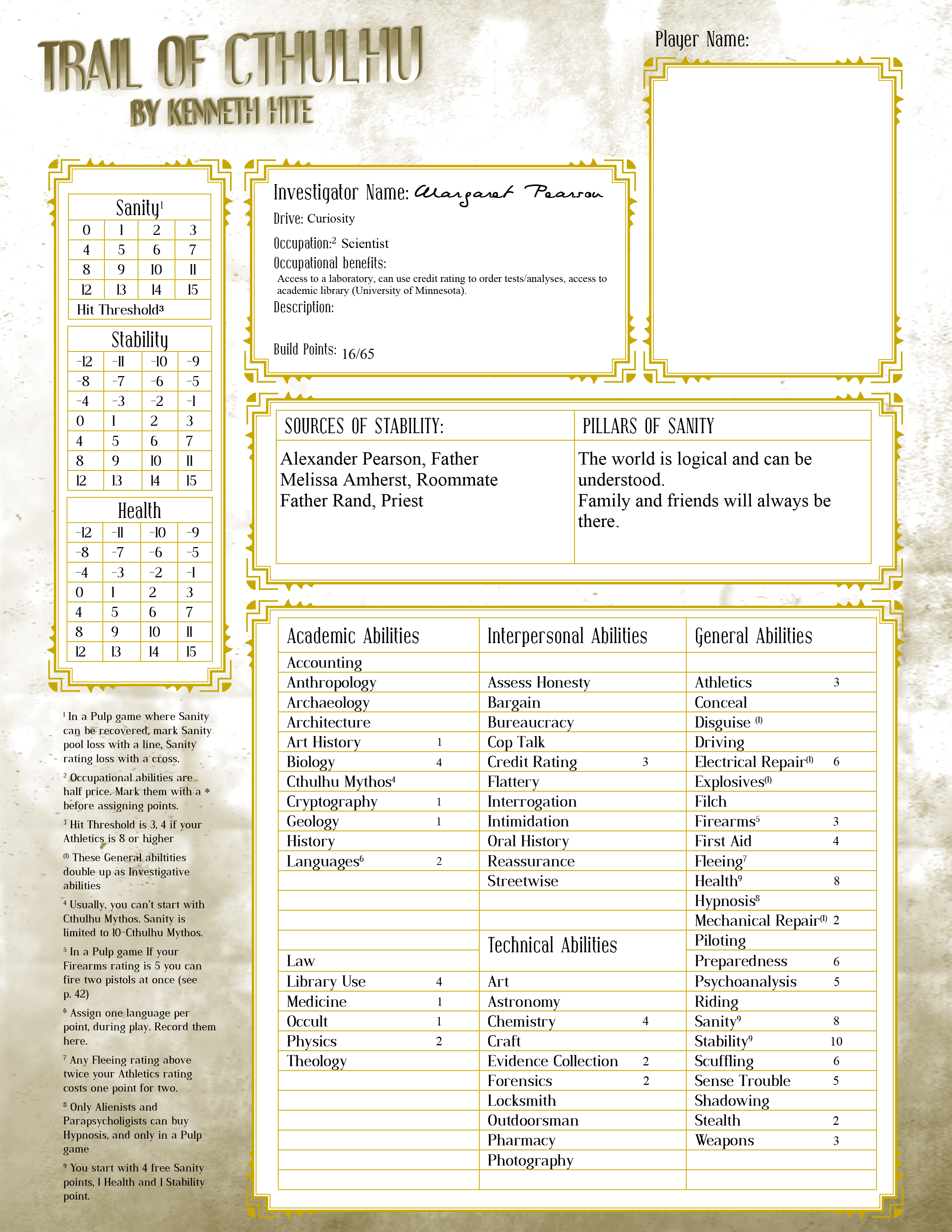

I generally think of dungeons as belonging to one of four categories:

- micro-dungeons

- mid-range dungeons (or session dungeons)

- large dungeons

- megadungeons

Micro-dungeons have just one or two featured rooms. These are rooms which have a significant interaction, like a combat encounter or in-depth investigation. Micro-dungeons will likely have additional scenic rooms, in which there is only one minor interaction (e.g., “look at this cool mural on the wall”), but likely only a few of them. Most micro-dungeons won’t have more than five rooms in total.

A micro-dungeon should generally take less than one session to play through. This means that they will not feature expedition-based play or significant strategic decisions by the PCs, but it does mean that they can be easily incorporated as a single scene or node in a larger adventure (even adventures that are designed to be resolved in a single session).

Of course, a micro-dungeon can also be a complete scenario in its own right (with a scenario hook, rapid resolution, and payoff). One interesting mode of play (or change of pace) is to resolve multiple such quests in a single session, creating a huge sense of momentum and accomplishment for the players.

Mid-range dungeons or session dungeons, as the latter name suggests, can be played from beginning to end in a single session. In practical terms, this means at least five featured rooms and an equal number of scenic rooms. In other words, you’d expect a mid-range dungeon to have a total of 10-20 rooms.

In terms of design, these dungeons are now large enough that you can start employing basic xandering techniques.

Assuming typical play, a mid-range dungeon will usually be resolved in a single expedition (i.e., the PCs will not need to leave the dungeon and then come back). In terms of 5th Edition D&D, however, I would expect that managing short rests would begin to be part of play, as opposed to a micro-dungeon where it’s likely the PCs will clear the whole dungeon before needing to rest. (See Resting in the Dungeon.)

Large dungeons are roughly three times larger than a mid-range dungeon. They’re going to feature 30+ rooms and will require multiple expeditions and several sessions of play. At this scale you’re going to be able to employ more elaborate xandering techniques and you’ll also begin introducing expedition-based play along with the management of long rests in 5th Edition.

This, of course, also means that you’ll likely start using restocking techniques, and so large dungeons will also change and shift during the course of play, becoming dynamic environments for exploration and strategic play. This is the point where simplistic “kick down the door” play is no longer sufficient… which is good, because that style of play can easily become monotonous and boring in a large dungeon.

Megadungeons, of course, are even larger. There are three key distinctions between a megadungeon and a very large dungeon:

- The megadungeon must have enough concept to support a full campaign. (This doesn’t necessarily mean a full 1st to 20th level campaign. For D&D 5th Edition, we might say that it has to be able to support two full tiers of play.)

- The megadungeon cannot be cleared (because it is too large and filled with too much content for that to happen). This means that “clear the dungeon,” which so often serves as a default goal for dungeon-based scenarios, cannot be a goal in the megadungeon. This will require the megadungeon to support alternative goals.

- This also means that the megadungeon must, in some way, contain multiple “scenarios.” It’s not unusual for each level of the megadungeon, for example, to have a particular theme or faction. At this level — pun intended — you can actually reintroduce “clear (this specific part of) the dungeon” as a goal, but the key thing is that the megadungeon is home to multiple distinct goals that can be independently, or semi-independently, pursued by the PCs. (The complexity and rich depth — pun once again intended — of the megadungeon also makes it likely that the players will begin setting bespoke goals for themselves.)

A megadungeon is, therefore, also sometimes known as a campaign dungeon, although there’s no reason that a campaign featuring a megadungeon can’t also include other scenarios.

LAIR vs. BALKANIZED DUNGEONS

A tangential categorization of dungeons that I find useful is the distinction between lairs and balkanized dungeons.

Lairs feature a single faction or type of monster. Everybody in the dungeon is playing for the same team, so to speak.

Balkanized dungeons, on the other hand, feature multiple factions. These factions may be openly hostile to each other or exist in some form of détente, but the key thing is that they’re not working together. (At least, not at first.)

This is significant because the balkanized dungeon, obviously, makes faction-based play significant in the scenario. In its most complex forms, this might involve the PCs navigating a web of unstable alliances in order to turn factions against each other, create places of safe respite within the dungeon, do quests for unexpected allies, and so forth. But even in its most simplistic form, it means that the PCs can defeat the dungeon in detail rather than tackling the entire compound all at once.

The balkanized nature of the dungeon will also inform the design of the dungeon, with defenses, no man’s lands between the factions, and the like.

The larger a dungeon gets, of course, the more likely it is to be balkanized. A micro-dungeon, after all, doesn’t exactly have the space for multiple factions. (Although you could imagine a couple factions-of-one.) But there’s no direct correlation: You can have multiple factions in a session dungeon and you can have large dungeons that are mono-faction hypercorp installations, goblin fortresses, or the like.

Preorder Now!