I’m calling shenanigans.

Of late the meme has arisen that the difference between “new school” and “old school” gaming is “rules, not rulings”. The free Lulu PDF A Quick Primer for Old School Gaming seems to be a primary infection point and I don’t think we’ll go too far wrong by quoting it:

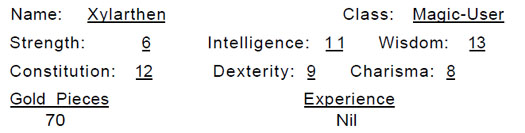

Most of the time in old-style gaming, you don’t use a rule; you make a ruling. It’s easy to understand that sentence, but it takes a flash of insight to really “get it.” The players can describe any action, without needing to look at a character sheet to see if they “can” do it. The referee, in turn, uses common sense to decide what happens or rolls a die if he thinks there’s some random element involved, and then the game moves on. This is why characters have so few numbers on the character sheet, and why they have so few specified abilities.

There are several problems with this meme.

BAD EXAMPLES

The Spot and Search skills tend to get targeted a lot by people trying to explicate the “rules, not rulings” concept. For example, the Quick Primer for Old School Gaming goes into a pair of lengthy examples of “old school” vs. “new school” play.

In the “new school” example, a player says they’re searching a hallway. They find a pit trap. They ask the GM if they can disarm it. The GM rules that they can. They jam the mechanism. (The results of the search and disabling attempt are handled by skill checks.)

In the “old school” example, a player says they’re checking the hallway. They fail to find the pit trap, but they’re suspicious so they try a different method of searching. They find the pit trap. They ask the GM if they can disarm it. The GM rules that it can’t be disarmed. They go around the trap instead. (The results of the search and disabling attempt are handled by GM fiat.)

Now, if you’re trying to establish that the difference in play here is GM fiat vs. dice rolling, then these examples would be just fine. But what the author actually does is load up the “old school” example with a bunch of details — using a 10-foot pole; carefully inspecting the floor; pouring water onto the floor to detect the edges of the trap — and then tries to attribute that additional detail to the GM fiat.

But the GM fiat has nothing to do with it. It’s an artificial conflation of two different distinctions between the examples. The use of GM fiat vs. predefined mechanics only matters in the moment of resolution. The amount of detail that goes into searching a particular stretch of hallway, on the other hand, is an entirely separate issue.

The “old school” example could just as easily read:

GM: A ten-foot wide corridor leads north into the darkness.

Player: I carefully check the floor for traps.

GM: Probing ahead you find a thin crack in the floor — looks like a pit trap.

Player: I try to jam it so it won’t open.

GM: No problem.

And the “new school” example could just as easily read:

GM: A ten-foot wide corridor leads north into the darkness.

Player: I’m suspicious. Can I see any cracks in the floor? Or a tripwire? Anything like that? [makes a Search check]

GM: Nope. There are a million cracks in the floor. If there’s anything particularly sinister about any of them, you certainly don’t see it.

Player: Hmm… I still don’t like it. I’m going to take my waterskin out of backpack. And I’m going to pour some water on the floor.

GM: [calls for a new Search check with a circumstance bonus for using the water] Yeah, the water seems to be puddling a little bit around a square shape in the floor.

Player: Can I disarm it?

GM: How?

Player: Jam the mechanism? [makes a Disable Device check; it fails]

GM: There’s no visible mechanism. The hinge must be recessed.

Player: Is there enough room to walk around it?

GM: About a two-foot clearance on each side.

Player: Okay, we’ll just try walking around it. Everybody watch your step!

Here’s a different example:

What I like mostly is more of the focus on descriptions rather than mechanics.

Player: “How wide is the ledge?”

GM: “Maybe 2 inches..”

(New School) Player: *seeing the modifiers of the Balance skill for that short a span* “Oh, nevermind, I better find another way across.”

(Old School) Player: “Okay … can I press myself up against the cliff face and side-step across?”

GM: “Sure. Since you aren’t pressured and can take your time, you don’t even have to roll anything.”

In other words, it’s more about player (and GM) creativity.

The poster here ascribes the difference to “creativity”, but that’s not what the example is actually demonstrating. Although the poster obfuscates it by giving different outcomes to the “old school” and “new school” games, the core of the example boils down to a single question: “Will I be able to cross this ledge?”

In the “old school” system the GM determines this by fiat (automatic success, automatic failure, or some probability of success based on an arbitrary dice roll). In the “new school” system the chance of success is determined mechnically.

Isn’t the “old school” GM getting to be “creative” because he determines the probability of success? I guess. But, of course, the “new school” GM also gets to determine the probability of success — he set that probability as soon as he described the ledge as being only 2 inches wide.

LOSS OF CONSISTENCY

So we’ve discovered that “rulings, not rules” is really just a mantra for, “I like GM fiat.” Fair enough. What’s the problem with pervasive GM fiat?

The loss of consistency.

Ben Robbins’ essay “Same Description, Same Rules” is an excellent summation of the problem. Here’s a quick quote:

Rules should not surprise players. More specifically, if you describe a situation to the players and then describe the rules or modifiers that will apply because of the situation, the players should not go “whaaaa?”

If they are surprised it’s either because you specified an odd mechanic (a will save to resist poison) or a really implausible modifier (-6 to hit for using a table leg as an impromptu weapon).

[…]

On the other hand if the same thing uses different rules on two different occasions, it’s hard to see how it makes sense no matter who you are. This might just be the result of inconsistency (oops) or you might intentionally be using another rule to get an advantage.

I recommend reading the whole thing. Robbins’ basic point is that players cannot make logical, informed decisions if their actions have inconsistent results.

The problem with pervasive GM fiat is that you are either (a) creating inconsistency or (b) creating house rules on the fly. And if you’re creating house rules on the fly then:

(1) You have to keep track of them.

(2) Hasty decisions will frequently have unintended consequences.

(3) Even if the house rule you came up with on the fly is good the end result is no different than if you’d had a good rule to start with.

OLD SCHOOL DID WHAT NOW?

So you say, “Screw that. Ben’s wrong. Consistency is vastly overrated.” Well, sure, that may be true. Everyone’s entitled to their own tastes and opinions after all.

But that really brings us to the crux of the issue: The whole concept of using “rulings, not rules” as a distinction between “old school” systems and “new school” systems?

It’s complete, unmitigated bullshit.

For example, take a peek at the example given in A Quick Primer for Old School Gaming: The difference between GM fiat and mechanical determination of success in finding and disabling traps. That’s a distinction that’s been around since the Thief class was first introduced in Supplement I: Greyhawk.

In 1975.

And if your contention is that the New School started in 1975, then I think it’s safe to say that your use of the term is out-of-synch with the way that most people use the term.

But this extreme example only highlights the other core failure of the meme: It claims that the great thing about the “old school” is the lack of rules (which, in turn, allows for GM fiat). But all of those “old school” games seem to feature all kinds of incredibly detailed, nitpicky rules — betraying a bugaboo for the exact sort of consistency that the “old school” movement is now trying to forswear.

Having a Search skill changes gameplay? Sure. But let’s not pretend that’s any kind of systematic preference for rulings vs. rules, because you know what else changes gameplay? Explicit mechanics for determining the loyalty of hirelings. And those rules are part of OD&D, but not 3rd Edition or 4th Edition.

The truth is that the game has moved towards GM fiat in some cases and away from GM fiat in other cases.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

There is, I think, a legitimate philosophical divison being alluded to here: The difference between “do what you want and we’ll figure out a way to handle it” and “you can only do what the rules say you can do”. But let’s not pretend that this is a division between “old school” and “new school” play. The term “rules lawyer” is older than I am.

In addition, I think the truth is that a properly structured rule system facilitates rulings — assuming, of course, that you’re not using the word “rulings” as an ad hoc synonym for “GM fiat”. The 3rd Edition skill system doesn’t just give you a tool for differentiating character concepts — it also provides a robust and open-ended mechanic which can be used to make any number of rulings.

It’s certainly possible to look at any ruleset as being a set of shackles that prohibits you from doing anything not explicitly proscribed. But, in my opinion, a properly designed ruleset is a flexible foundation on which an infinite number of structures can be securely built.

Honestly? The whole “rules, not rulings” thing was a valiant effort. But you’re going to have to keep trying if you want something more than “old school is what I point to when I say ‘old school'” as your definition.