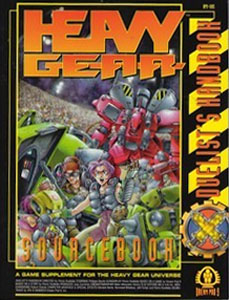

Tagline: Dream Pod 9’s chance to celebrate their mascot, with spectacular results.

Tagline: Dream Pod 9’s chance to celebrate their mascot, with spectacular results.

If you’ve read any of the reviews of the Heavy Gear game you’ve probably heard a familiar theme: Sure, there are mecha… but the game isn’t about the gears. The reason you’ve heard this is because, well, it’s true. The gears are definitely cool, and they’re definitely the most realistic mecha you’ll probably ever encounter, and they are definitely eye candy without par. All that being said, however, the game is really about characters. The Gears aren’t even the “Gods of the Battlefield” the way mecha are usually portrayed. As a result, the sourcebooks tend to deal with the gears in a fairly secondary matter, focusing instead on generalized world-building. Even the vehicle compendiums offer a generalized mix.

Welcome, then, to The Duelist’s Handbook, Dream Pod 9’s chance to celebrate their mascot. And what a celebration it is.

The other heritage which The Duelist’s Handbook inherits is that of the defunct Heavy Gear Fighter card game. HGF was the first Heavy Gear product released by Dream Pod 9 and introduced the dueling concept. As Phil Boulle details in his Behind the Scenes for the book, Into the Badlands allowed the concept of dueling to be expanded from affairs of inter-regimental into the underground, competitive dueling of Khayr ad-Din. The Duelist’s Handbook, as a result of this heritage, details the ritualized rules of Gear dueling; provides a look at the stars of the dueling world; examines the lives and duties of military duelists; provides a host of new weapons and options for Gears; and, finally, serves as a sourcebook for the city of Khayr ad-Din.

Normally I wouldn’t like a book like this. Typically when a roleplaying sourcebook is primarily a technical one (i.e. the title of the book includes the technical term “duelist” rather than a location name like “Khayr ad-Din”) and then includes a setting of some sort, that setting is usually merely tacked on. It is almost never given the justice it deserved, if it deserved any justice at all (more often than not such settings are a poorly conceived set of stereotypes which apparently exists only to highlight elements found in the technical section of the book).

Would it really surprise you if I told you that Dream Pod 9 avoided falling into that trap? First off, the technical aspects of the book are handled with grace and style. Military dueling, competitive dueling, and the worlds which surround both are described in great detail. Additional weapons, gears, and detailed rules for small scale tactical combat are given. Second, the setting of Khayr ad-Din (a shadowy city built in an around a massive dumping ground) is detailed with typical craft and style of Dream Pod 9, with an eye always pointed towards providing not only a living, breathing, believable setting of incredible depth, but also a setting which provides countless adventuring possibilities. Plus there is nothing “throwaway” about Khayr ad-Din or its duelers (as anyone who has perused the latest offerings of the storyline books knows).

Beyond the quality of the material itself, Dream Pod 9 continue to demonstrate their enormous talent at putting a book together to make it not only practical, but beautiful. The Duelist’s Handbook was one of the transition products where the Pod slowly developed their lay-out skills from the earlier works which were possessed of a slight “page crowding” sensation (although still exceptional by the standards of the industry) into a cleaner feel. Again, one of those differences between being “one of the best” and “true excellence” which the Pod has demonstrated mastery of time and again. The information is always grouped in an intuitive manner and the index is detailed in all the right places. Typically, the Pod demonstrates that they are capable of “throwing away” artwork which other companies would gladly use on their front covers.

Although the Pod is apparently letting this one slip out of print for at least the moment, you should still be able to find it in stock somewhere. Grab it up, you’d be missing out on a good thing if you let this one pass you by.

Style: 5

Substance: 5

Author: Philippe R. Boulle

Company/Publisher: Dream Pod 9

Cost: $19.95

Page Count: 128

ISBN: 1-896776-07-8

Originally Posted: 1999/04/26

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.