Location-based adventures are a staple of the GM’s art and form a kind of bedrock for scenario design. Even if a scenario isn’t primarily about ‘crawling a specific location, you’ll still find yourself frequently keying a map to describe wherever the action is taking place.

Which is why I find it fairly surprising that the location keys in published adventures are almost universally terrible.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE KEY

In 1974, the original edition of D&D included a “Sample Map” keyed with both numbers and letters. The description of the key, however, was instructional rather than practical. For example:

5. The combinations here are really vicious, and unless you’re out to get your players it is not suggested for actual use. Passage south “D” is a slanting corridor which will take them at least one level deeper, and if the slope is gentle even dwarves won’t recognize it. Room “E” is a transporter, two ways, to just about anywhere the referee likes, including the center of the earth or the moon. The passage south containing “F” is a one-way teleporter, and the poor dupes will never realize it unless a very large party (over 50’ in length) is entering it. (This is sure-fire fits for map makers among participants.)

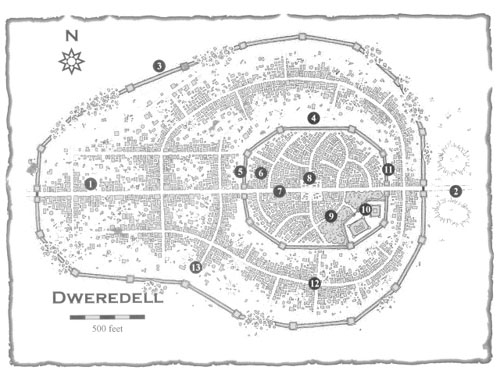

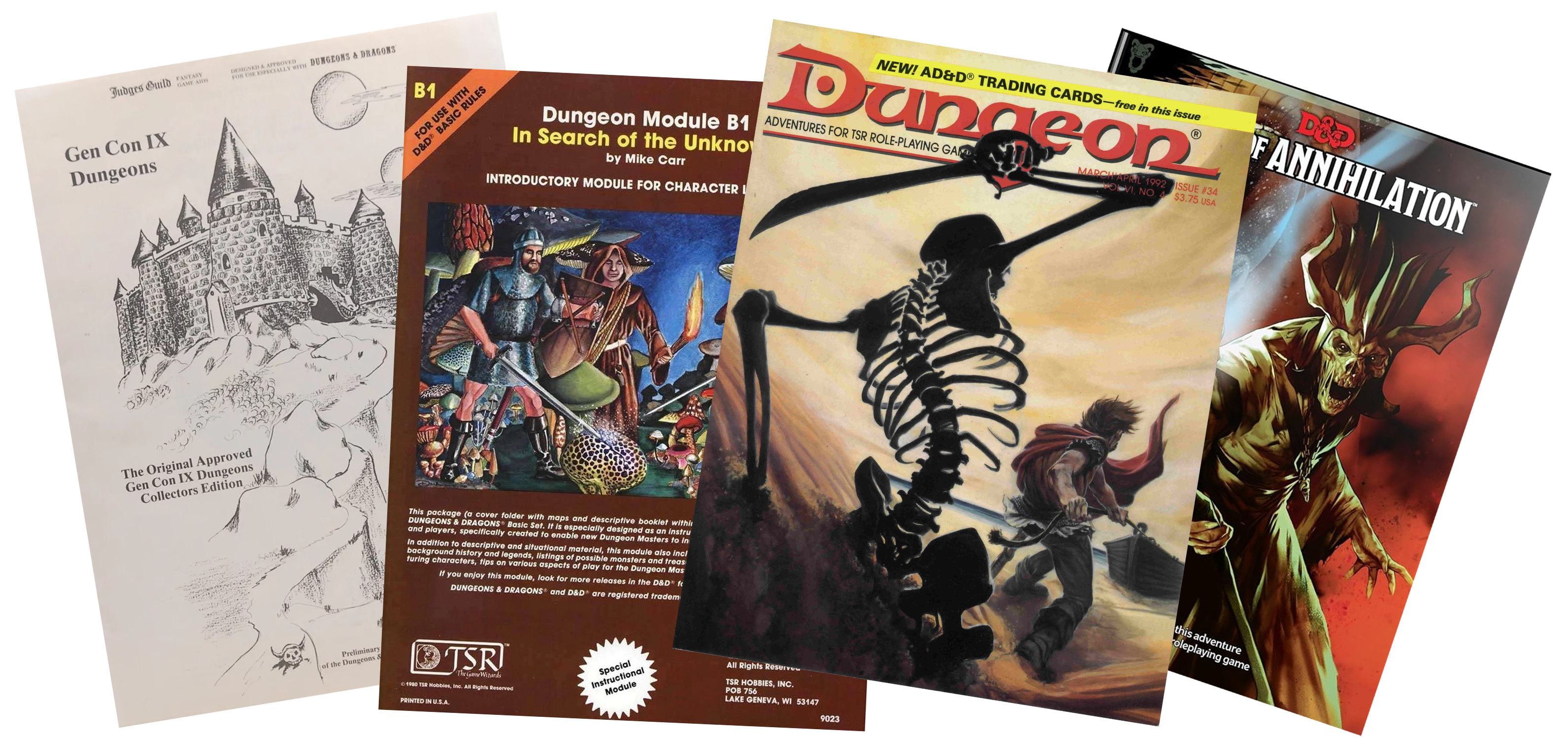

Skip ahead a couple of years to 1976, though, and we’ve reached Year One for published adventures: Arneson’s “Temple of the Frog” appeared in Supplement II: Blackmoor; Wee Warriors released Palace of the Vampire Queen; Metro Detroit Gamers released the original Lost Caverns of Tsojconth; and Judges Guild released Gen Con IX Dungeons and City-State of the Invinicible Overlord.

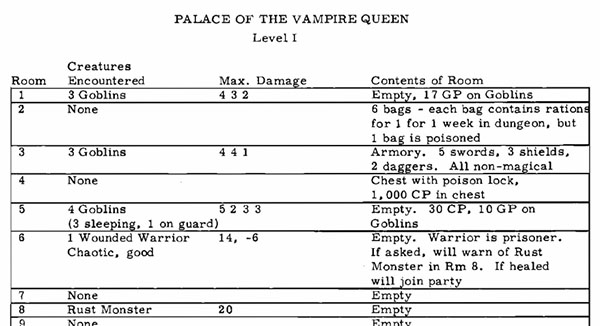

Palace of the Vampire Queen featured a completely tabular key that looked like this:

The Lost Caverns of Tsojconth, on the other hand, featured the Gygax “wall of text” key which would become a staple at TSR for the better part of a decade:

K. COPPER DRAGON: HP: 72. Neutral, intelligent, talking, has spells: DETECT MAGIC, READ MAGIC, CHARM PERSON, LOCATE OBJECT, INVISIBILITY, ESP, DISPEL MAGIC, HASTE, and WATER BREATHING. It is asleep but will waken in 3 melee rounds or if spoken to or attacked. It will bargain to allow the party to pass on to the east if given at least 5,000 GP in metal and/or gems/jewelry – deduct 1,000 GP for each magic item offered instead. It will tell the party nothing, but it will ask about the fire lizards. If the party has slain these creatures, the dragon will attack them. 30,000 CP, 1,000 GP, 36 100-GP gems, 42 500GP gems, 13 1,000-GP gems, 9 pieces of jewelry (9,7,7,6,5,4,,4,3,3 in 1,000’s each). A jeweled sword (quartz), non-magical, will be hated by party’s swords at first, value is 783 GP. An ivory tube with contact poison contains a scroll of 3 spells (MONSTER SUMMONING III, LIMITED WISH, SYMBOL). Several pieces of jewelry radiate magic (they have a magic mouth spell on them with a nearly impossible speak command) for a 10th piece of jewelry is a necklace of missiles (5), with each missile globe encased in an ivory block (which can be pried open along a hairline seam to reveal the missile).

In Gen Con IX Dungeons, meanwhile, Judges Guild was way ahead of the curve (as was so often the case). Bob Blake had recognized that a key with better organization would make it easier for DMs to run the adventure, and he introduced that organization by including a “DM Only” section in each key entry:

13. 30’ N-S, 30’ E-W. Enter by secret door in center of W Wall. There is a blackened firepit in the center of the room, and a barred opening into 10’x10’ opening in the center of the E Wall.

DM Only: The firepit contains nothing of value. The portcullis may be easily raised by pulling on a chain hanging from a small hole in the wall next to the portcullis. There is a secret door in the E Wall of the alcove.

Although not technically boxed text, this format was effectively accomplishing the same thing on a structural level. (Particularly interesting are the keys which feature two separate “DM Only” sections – one before the player section and detailing information necessary when entering the room and one after the player section detailing information on what investigating the room will reveal.)

Unfortunately, although Blake used this format through 1977, Judges Guild eventually abandoned it and also moved to “wall of text” keys.

In 1978, B1 In Search of the Unknown effectively created the idea of separating the key into distinct sections:

30. ACCESS ROOM. This room is devoid of detail or contents, giving access to the lower level of the stronghold by a descending stairway. This stairway leads down and directly into room 38 on the lower level.

Monster:

Treasure & Location:

Although this division superficially resembles later “adventure formatting guides” (which we’ll get to momentarily), it was actually an accidental by-product of In Search of the Unknown being designed as a training tool for beginning DMs: The adventure included prepared lists of monsters and treasures which the neophyte DM was supposed to assign to various rooms throughout the dungeon. (Which is why those sections are blank in the example above.)

THE ERA OF BOXED TEXT

In either 1979 or 1980, depending on how persnickety you want to get with definitions, boxed text — prewritten text designed to be read aloud by the GM — arrived for the first time in Lost Tamoachan: The Hidden Shrine of Lubaatum, a tournament module by Harold Johnson & Jeff R. Leason that was originally printed for the Origins game convention.

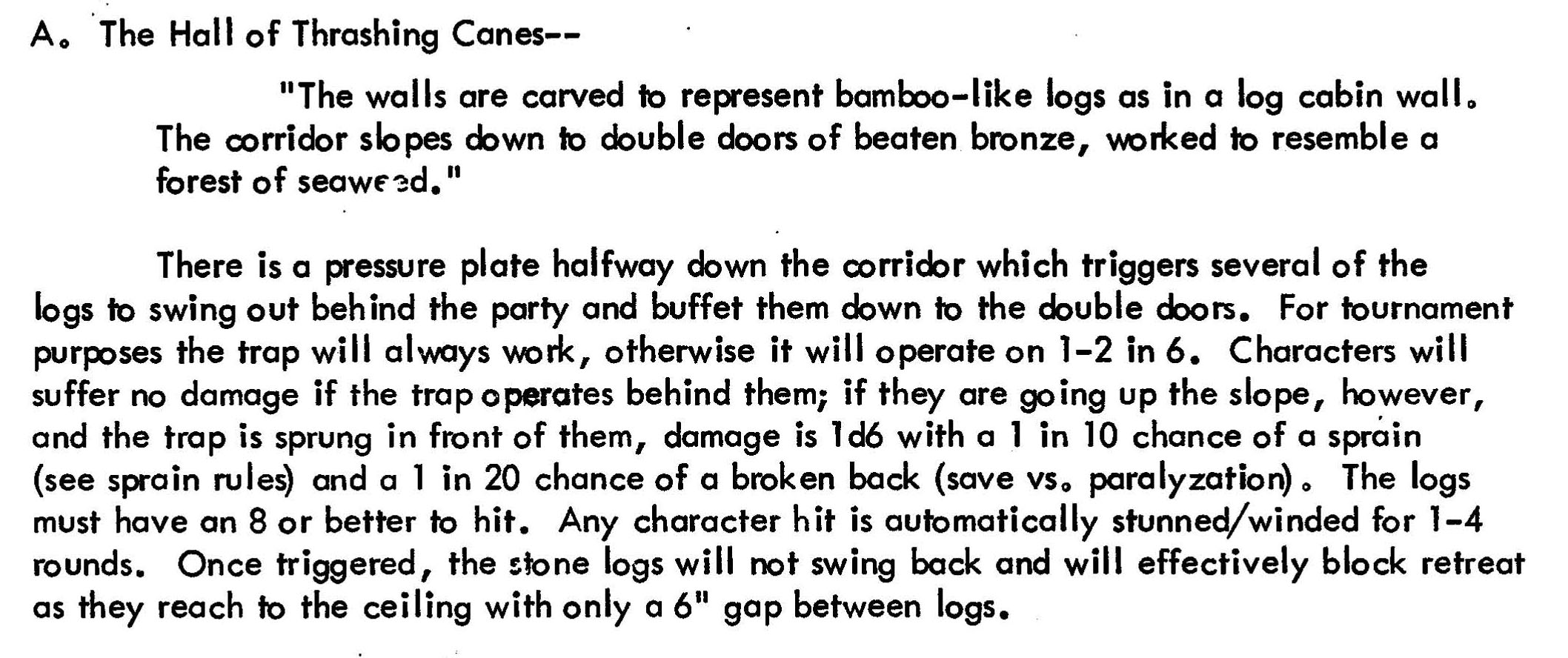

In the original version of the module, the text was not yet boxed, instead appearing between quotation marks:

But in 1980, TSR reissued the module as C1 The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan, placing the prewritten descriptions in a box for the first time:

![2. The Hall of Thrashing Canes:

[BOXED TEXT] The sides of this corridor are carved to resemble walls of bamboo-like logs. The passage slopes down from a single door on its western leg, the lintel of which has been crafted to represent a stylized cavern entrance, to double doors of beaten bronze, worked to resemble a forest of seaweed. [END BOXED TEXT]

There is a pressure plate halfway down the hallway which triggers a trap. Several of the logs will swing out from either wall and buffet the party towards the double doors. For tournament play, the trap will always work. For campaign adventure, the trap will be triggered on a 1 or 2 in 6.](https://thealexandrian.net/images/20140519f.jpg)

Like Blake’s “DM Only” section from earlier in the decade, the boxed text clearly delineated the elements of a given area that should be immediately shared with any PC entering the area.

Later, of course, the role of boxed text would be expanded to include any sort of “read-aloud” text intended for the players, but its function as a narrative device is beyond the scope of location keying. In this context, however, an honorable mention should perhaps be given to Quest of the Fazzlewood, a 1978 “head-to-head” tournament module designed to be played with just one DM and one player. In addition to a lengthy introduction designed for the player to read, the finale of the adventure is presented with read-aloud text:

(photo from Explore: Beneath & Beyond)

The formatting is quite similar to the later Lost Tamoachan, and one could argue that this is, in fact, the first example of “boxed text” (albeit of the not-yet-boxed variety).

In any case, at this point, things basically settle down: When Dungeon #1 appeared in 1986, it still featured the familiar boxed text paired with a “wall of text” key for the DM. In 1988, monsters and NPCs in the magazine received a standardized stat block that gets clearly delineated from the text. But that basic format can still be seen in The Apocalypse Stone in 1999 (the very last adventure produced for 2nd Edition).

ADVENTURE FORMATTING GUIDES

When 3rd Edition arrived, however, an effort was made to introduce a new “standard format” for published adventure modules. First appearing in The Sunless Citadel, this format had the familiar boxed text and wall of text, but supplemented this with a specific set of bold-faced sections:

- Traps

- Creatures

- Tactics

- Development

- Treasure

Not all of these appeared in every location, but if they did appear then they appeared in that order and no other.

As noted above, this format recalls B1 In Search of the Unknown. There were also a handful of other examples between 1978 and 2000, most notably 1982’s I3 Pharaoh which featured headings for:

- Play

- Lore

- Monster

- Character

- Trap/Trick

- Treasure

Tracy and Laura Hickman, the authors of Pharaoh, also dedicated a full page to explaining what each section of their key was designed to accomplish. For example:

Play: This outlines the general sequence of events that may take place in the room. For example: “Players entering the room from the door must first encounter the Trap, which releases the Monster. Only by defeating the Monster can the Treasure be found.” Play explains the general order that the sections should be used. Additional size and dimension information about the area is also included here.

And that largely explains what the intended purpose of the standardized adventure format is: To break up the wall of text and clearly communicate to the DM where they should look for a given piece of information.

It’s a noble intention, but the problem with this specific approach to adventure writing is that it tends to encourage writers to “fill the format”. You probably don’t really need to tell a DM that the orcs attack people using their swords (since that’s the only weapon they have)… but the format says you should have a “Tactics” section, so you might as well write two or three paragraphs about it.

An even bigger problem, in my experience, is that of sequencing information: A room with an ogre standing in the middle of it should talk about the ogre first; a room with a goblin hiding behind a tapestry, on the other hand, shouldn’t lead off with the goblin.

This sort of one-size-fits-all formatting becomes both a straitjacket and an excess. And the culmination of this approach is the infamous “delve” format, which I’ve talked about extensively elsewhere.

The fundamental problem (which the delve format simply metastasizes) is that the rigid adventure format forces information to be presented out-of-sequence or breaks that information up in a way that doesn’t make sense during actual play. Instead of making the information easy to parse and reference, a rigid format ends up having the opposite effect.

THE ART OF THE KEY

Part 2: The Essential Key

Part 3: Hierarchy of Reference

Part 4: Adversary Rosters