There are, in my opinion, two big lessons to take away from our review of the history of location keys: First, there is an obvious need to separate information that should be immediately available to the PCs from the more detailed information in the room.

There are, in my opinion, two big lessons to take away from our review of the history of location keys: First, there is an obvious need to separate information that should be immediately available to the PCs from the more detailed information in the room.

Second, there is a clear and logical desire to break up and organize the information in the key so that the GM doesn’t have to wade through a wall of text in order to pluck out the information that they need at any given moment.

The real question, of course, is how the information in the key can be effectively organized for the GM’s use. We’ve already rejected the idea of a rigid or dogmatized format, but there has to be something better than just puking everything out onto the page and hoping you can pick out the useful bits later.

The ultimate solution, in my experience, is to focus on the sequencing of information: How the information will flow (or is likely to flow) at the actual gaming table.

TITLE OF THE ROOM

Start with the title of the room. Technically, this is optional, but I find that a good title instantly orients you: It tells you what type of room it is and can also serve as a valuable reminder and touchstone if you’ve familiarized yourself with the adventure.

BOXED TEXT

We start with boxed text which conveys the common information that anyone walking into the room would immediately perceive. (“You see a box in the corner with a weird symbol painted on it.”)

This doesn’t have to literally be text in a box, of course, but it should be clearly delineated from the rest of the key and contain all of the information that should be immediately conveyed when the PCs first enter the room. I also think of this section as seen in a glance.

Brendan over at Necropraxis makes the interesting point that if you’re confronted with a wall of text in a published module, you can often yank out a useful “seen in a glance” section by strategically using a highlighter. Here’s an example from the Tomb of Horrors:

It was actually while attempting to run the Tomb of Horrors that I first realized how important it was to clearly segregate the “initial player briefing” for an area from the general description of that area. (And also the importance of making sure that the initial briefing is complete and accurate.) This is actually what led me to create a complete revision of the Tomb specifically designed to make it easy for the GM to run it.

REACTIVE SKILL CHECKS

Directly after the boxed text are the reactive skill checks which should be made immediately by anyone entering the room. These are typically perception-type checks, but they might also be knowledge checks. (For example, a See Hidden roll to notice that there are small spiders crawling all over the box. Or a History check to recognize the symbol on the box as the royal seal of Emperor Norton.)

It’s actually surprising to me how often I see this type of information mishandled in published adventure keys. For some reason you’ll get six paragraphs describing the room in detail and then, buried somewhere near the bottom, the author will suddenly reveal that the PCs should have made a Spot check to see if they notice that the ceiling is coated in flammable oil. (What this usually means at the table is that the PCs will have spent several minutes exploring all the stuff described in those first six paragraphs before I notice that a Spot check should have been made 10 minutes ago. Whoops.)

SIGNIFICANT ELEMENTS

At this point, each significant element in the room is independently described with additional details that will become important if characters investigate or interact with it. (“Inside the chest is a ruby which has been cracked in half. You can see that the inside of the ruby is filled with empty spider’s eggs.”)

What constitutes a “significant element”? Basically anything that the GM needs more information about. Most of the time that means anything that the players are likely to interact with or investigate.

This is usually pretty self-evident. For example, look back at that highlighted example from Tomb of Horrors. If you started grabbing significant elements from the “seen in a glance” stuff, you’d end up with something that looks like this:

Old Jars: Filled with dust and impotent ingredients of all sorts.

Clay Pots/Urns: These obviously once contained unguents, ointments, oils, perfumes, etc.

Vats: Each of these vats contains murky liquid. They are affixed to the floor and too heavy to move.

Notice that the bold title makes it easy to find the information you need. It also makes it easy for the GM to quickly process what the room contains and how it “works” in play. (What’s in this room? Old jars, clay pots, urns, and some vats. What happens when they look in the jars? They see that they’re filled with dust and impotent ingredients.)

DEVELOPING SIGNIFICANT ELEMENTS

Let’s focus on those vats a bit more.

Obviously I’m cheating with the key above because there’s a lot more information about those vats in Gygax’s original key. We could certainly just plop all that info into a big paragraph:

Vats: Each of these vats contains murky liquid. The 1st holds 3’ of dirty water. The 2nd contains a slow-acting acid which will cause 2-5 h.p. of damage the round after it comes in substantial (immersed arm, splashed on, etc.) contact with flesh – minor contact will cause only a mild itch; at the bottom of this vat is one-half of a golden key. The 3rd vat contains a gray ochre jelly (H.P.: 48; 4-16 h.p. of damage due to its huge size) with the other half of the golden key beneath it. The vats are affixed to the floor and too heavy to move. The key parts are magical and will not be harmed by anything, and if the parts are joined together they form one solid key, hereafter called the FIRST KEY. As the acid will harm even magical weapons, the players will have to figure some way to neutralize or drain off the contents of the 2nd vat, as a reach-in-and-grope-for-it technique has a 1% cumulative chance per round of being successful.

But it’s pretty easy to see how we just end up with a wall of text again doing that.

What we need to do is break that information down even further. I typically do that with bullet points, although really any sort of hierarchical structure will work just fine. More important than the particular method, however, is the methodology behind it: What you want to do is to move from the general to the specific while paying particular attention to how the players are gaining that information.

There’s some useful reading on this topic over at Courtney Campbell’s Hack & Slash: “On Set Design”. The specific method Courtney lays out over there is pretty heavily dogmatic and far too limited in its application for my tastes, but the specific way that he conceptually breaks down a room key is useful. Expanding on his basic thoughts, I would say something like this:

- List all the visible items in the room (i.e., vats).

- Beneath those items, list information that would be gained by simply looking more closely at the object (i.e., the vats have liquid in them). Then list information that requires specific actions to be taken to discover (i.e., the liquid in the 2nd vat is acid). (This latter category notably includes items which are found within a container.)

- Now do the same thing for items or features of the room which are not immediately visible (i.e., a secret door that requires a Search check).

The logic here should be fairly obvious: In interacting with a room, the players are most likely to start by asking questions about the things they’ve just been told about (so put information about those items up front). They’ll start with general questions and then proceed to detailed investigation (so put the information in that order).

The point, of course, is not to say “this is the order in which they must search the room”. You’re just organizing the information in the way that makes the most sense. And if it makes more sense to put information about some hidden element of the room first because it provides important context for the other stuff… well, do it. We’re just discussing a useful way of thinking about how to organize the information, but actual adventures are idiosyncratic so break down and organize the features of the room in whatever order makes sense to you.

GM BACKGROUND TAG

Over the past few years, I’ve found one other distinction particularly useful in my location keys: The “GM Background” tag.

Here’s a simple example from a recent adventure in my Ptolus campaign:

9. UNFINISHED ANTI-FEAR DEVICES

Four unfinished clockwork devices atop copper rods lie on the floor or lean against the walls.

Fear-Cleansing Devices: These are partially completed fear-cleansing devices (see area 1).

- Arcana (DC 30): To reverse engineer them and complete them (1d4 days).

- GM Background: These were to be installed in this area and north of area 20, but the work was never completed.

The point of the tag is to include details that can provide important context for the current location without cluttering up the functionality I want to be able to quickly reference during play. For example, this same key without the GM Background tag would look like this:

9. UNFINISHED ANTI-FEAR DEVICES

Four unfinished clockwork devices atop copper rods lie on the floor or lean against the walls.

Fear-Cleansing Devices: These are partially completed fear-cleansing devices (see area 1). These were to be installed in this area and north of area 20, but the work was never completed.

- Arcana (DC 30): To reverse engineer them and complete them (1d4 days).

It’s a minor example, but hopefully you can see how the primary description of the fear-cleansing devices is now slightly more cluttered and a little more difficult to process quickly.

The tag is particularly useful for information of the “this is what this ruined room used to be” and “this is what the NPCs use this room for” variety. Instead of saying “the room is filled with broken, ruined furniture” and then providing a lot of details about the furniture in your key, it’s a lot easier to say “the room is filled with broken, ruined furniture (and it used to be a barracks)”. If the PCs start poking around the broken furniture, the background information gives you enough context to improvise the details.

A word of caution with the GM Background tag: It should be brief, to the point, and infrequently needed. If you find your room keys becoming dominated by background information it’s likely that you’re doing something wrong: Refocus your attention on the stuff that PCs can actually learn (and how they can learn it).

THE FULL KEY

And now we can put it all together.

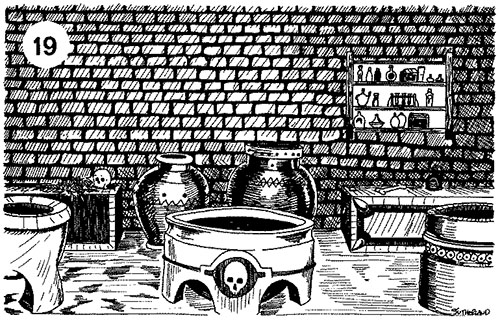

19. LABORATORY AND MUMMY PREPARATION ROOM

All of the walls in this chamber are lined with shelves and upon these are old jars. There is a large desk and stool, two workbenches, and two mummy preparation tables. There are clay pots and urns on these tables and the floor. Linen wrappings are in rolls or strewn about. Dried herbs of unidentifiable nature, bones, skulls, and the like litter the workbenches. In the south are three vats of about 7’ diameter and 4’ depth.

Spot (DC 15): To notice a lack of dust around the third vat.

- GM Background: This lack of dust is due to the presence of the grey ochre jelly.

Old Jars: Filled with dust and impotent ingredients of all sorts.

Clay Pots/Urns: These obviously once contained unguents, ointments, oils, perfumes, etc.

Vats: Each of these vats contains murky liquid. They are affixed to the floor and too heavy to move.

- Vat 1: Filled with 3’ of dirty water.

- Vat 2: Filled with slow-acting acid. Minor contact will cause a mild itch. Substantial contact with flesh (immersed arm, splashed on, etc.) will cause 2-5 hp per round. The acid will harm even magical weapons.

- Golden Key Part: Beneath the acid is ½ of a golden key. A reach-and-grope-for-it technique has a 1% cumulative chance per round of finding the key.

- Vat 3: Contains a gray ochre jelly (48 hp, 4-16 hp of damage due to its size).

- Golden Key Part: Beneath the grey ochre jelly is ½ of a golden key.

Golden Key Parts: The key parts found in the vats are magical and will not be harmed by anything. If the parts are joined together they form one solid key, hereafter referred to as the FIRST KEY.

Of course, not every location key needs to be this complicated. But if you compare this to the “wall of text” version from the original module, I think it should be fairly obvious how much easier it will be to navigate and use this key in actual play: Read (or summarize) the boxed text. Scan the bolded points of interest. Follow the players’ lead.

I find that when I’m working with keys in this format I can generally pick up material and run it on-the-fly even if I haven’t reviewed it in weeks or months. With the types of keys being published in the industry today, however, I can’t do that: There’s no easy way to efficiently parse and run keys featuring multiple paragraphs (and often multiple pages) of poorly organized and undifferentiated material.

HOMEBREW vs. PUBLISHED

The final thing that should be mentioned here is that there’s been a certain degree of “polish” attendant to most of my discussion of the location keys so far. This is a natural consequence of trying to communicate clearly with you, but it’s not necessarily a great example of how you should actually do it at home.

When you’re prepping location keys for your own campaign, you don’t need to be so neat and tidy (nor so loquacious). Bullet point your boxed text; jot down quick notes. Whatever works for you. Complete sentences are overrated: Get the information across in the most efficient fashion possible.

Remember: Your location key is not the work of art. It is a tool that you use to create awesome stuff at the gaming table.

Hone that tool, treat it well, and it will pay you back a hundredfold.

Thank you for writing this up — it makes quite a bit of sense and clarifies ideas I’ve been groping towards blindly for a while. Looking over my map & key for tonight’s game, I can immediately see where following this advice will improve the presentation. Oh well, there’s always next time.

That’s way too much boxed text. Whether you should have any boxed text is another question, but if you try to read that aloud, your players will miss it.

http://www.wizards.com/default.asp?x=dnd/dd/20050916a

You can and should not give the sizes of the vats, putting that later. Same story with the mummy table, since a first glance doesn’t give its aim. The linen wrappings should be something on the tables, if the players give them a harder look, and belong with that description. Same with the herbs.

I’d significantly rewrite that boxed text in practice, too, but I wanted to keep as true to Gygax’s original phrasing as possible. (To emphasize that my primary point here refers to organization of information and not simply rewriting Gygax’s verbose prose.)

However, I disagree with the general sentiment that it’s impossible for the players to process 5 short sentences of information.

I also disagree with the specific idea of genericizing the description of the clutter in the room. That’s a good way to end up with bland and uninteresting room descriptions that have no distinction from each other.

First, thanks!

Second, the presentation is dogmatic, because it’s the presentation of a radical new approach to information design. The use of the concept in practice is, well, this post is a great example!

The topic is quite complex. The article is using a megadungeon as the example keyed, whereas a site based adventure (like tomb) has different needs. The concept when applied to an actual adventure needs to be fluid, and the presentation of a single room can’t be compared to how that room is presented in the larger context of a published module.

Awesome! I have been thinking about better structures for adventure write-downs for some time, but didn’t get many results (maybe due to the lack of adventures on my shelf). This idea is really a major improvement. Surely everybody has his or her own priorities, but I’m sure that this will result in at least some improvement for anyone. I hope to find such structure in published adventures soon!

One thing I probably would add to this approach is to make the significant items in the boxed text non-italic to allow an even quicker scanning and to let the gm make up his very own description and not missing any important items. I think the non-italics don’t distract too much, but are quickly found.

Notre, what I still need would be such an approach to the adventure as a whole, the plot parts. There are currently still many walls of text, which makes prepping very time consuming and finding information at the table absolutely nasty.

I think in a published adventure it is reasonable to expect rather extensive GM background because it helps the GM develop a mental picture of each area. However, the failure to separate this from “the facts on the ground” that the players encounter is a usability problem.

Justin, which of your published adventures provides the best example of your template being put into practice?

Hi, I liked this post (and most of the linked ones as well). I would be interested to see how you would write up a wilderness hex covering a decent sized area. Maybe just subdivide it down?

@Randy: Hexcrawls – Part 8: Sample Hex Key.

Ask and ye shall receive. 😉

I like this approach, adapted from Fr. Dave’s method.

http://fictivefantasies.files.wordpress.com/2012/07/scaled-lords-swamp-domain.pdf

Excellent write up, Justin! Paragraph sequencing without the boxed text is an excellent idea that works. Andrew’s method is better handled via paragraph sequencing with the obvious first, and then that, which can be discovered upon searching. I do not believe in reactive skill checks, reactive skill check being a saving throw, when a player misses something. Player actively looking and searching is everything. The player slowly advancing down a corridor looking for traps is when a passive skill check is used. The only thing that is tabulated are the in-game combat stats for the monsters and in game mechanics for check modifiers etc. Highlighting important text is an excellent idea as well. I like the GM background paragraph and will implement my ideas in my adventure writing.

One thing I would add is that room descriptions tend to be passive and if there is an active, intelligent and organized force opposing the players, whether in a dungeon or in a campaign, I like to write a version of the classic Five Paragraph Warning Order for each adversary: the Situation, Mission, Execution, Administration, Command and Communication structure from the US Army. This is something written and issued to troop patrols before they go out in the field: Paragraph -1: Situation – What’s going on with THEM (originally used to describe the types and locations of the friendly and enemy units in the area of operations); 2: Mission – What THEY are doing, what THEY are trying to accomplish; 3 – Execution: How THEY are going about doing it; 4 – Administration – listing of THEIR forces and resources, that THEY can bring to bear on the players and how they react to players and interact with each other; 5 – Command and Communication: Which outside forces in the campaign THEY deal and interact with, how they communicate. I do this for two reasons: It creates a more dynamic profile for the opposing forces that the players may come in contact/combat with during the game, and also, to program complex planning that players can come up against and either defeat or be defeated by without the DM improvising or cheating against players by using ALL of his knowledge as opposed to running the opposition based on what the information that the opposition will have and according to a set plan. At the end of the adventure, I let the players read my adventure materials if they so desire, to show them that I actually ran an adventure and did not play against them or helped or hindered the players as DMs often do. Also, I can assign objective experience bonuses for the milestones in overcoming and defeating, or dealing with the various forces in the campaign.

One other trick I like doing is using Excel to compare and contrast various factions in the campaign and on the game map: The table headings are Criteria for comparison and then various noble families, thieves guilds, etc. Criteria might be: how many men at arms, what weapons, main sources of revenue, relationship with the King, etc. Over time this grows into a detailed big picture that you can readily implement into local adventures. Second trick is to use MS Access to put all of the monsters and spells and magical items into a database, and then retrieve it as necessary for the adventure design and the encounter tables. I play AD&D, so for my monsters I have the Monster Manual, Monster 2 and Fiend Folio. It speeds things up considerably to be able to type in: Humanoid, Level 1-3, Steppe, Grassland, Field and to get a listing of D&D creatures, obvious and obscure, for my consideration.

Very useful indeed! A question: did you do this with Caverns of Thracia? On you advise, I got the original module in PDF format from Judges Guild, but on a first glance there seems to be a wall of text as well. I wondered if you made modifications to it or if you just ran it as it is. For example, I find the key to the corridor on the first level marked as 8 is missing, only by reading your article I realized it was a slope that led to level 2.

I’m afraid I ran Caverns of Thracia almost entirely from the printed module (walls of text notwithstanding). It helps that Jaquays kind of instinctively prioritizes the information in most of the areas. As a simple example, consider the description of area 3:

“At the north end of the alcove is a pile of rubble that appears to have once been a stature of a sort. If the rubble is dug through (approximately 1 turn) the head can be found. It will be the head of the goddess Athena. The door into Room 5 is ajar and the door to Room 4 is jammed shut so that it is a -1 on opening capability. If characters choose to notice, they will find that it appears that trails have been worn through the muck on the floor, leading to both Rooms 4 and 5 and into and through Rooms 2 and 1.”

You can see how it starts with the stuff you can immediately see, develops each of those with possible interactions, and then talks about stuff that isn’t immediately apparent. It’s not perfect (and some of the areas are less friendly), but even this minimal sense of how the information for a given area connects together makes it relatively easy to run from the book.

What I did maintain for the Caverns was a “change document” to track the changes resulting from PC actions. This includes monster rosters and short updates like:

AREA 1: Bats have been eaten by spiders. Spiders have been killed. Wisps of webs; bats drained dry; and dead giant spider babies.

AREA 23: The Voodoo Man is currently encased in swirls of black energy upon the altar. They are trying to imbue him with the ability to control the undead in area 27B.

AREA 51: This was the Shrine of Saint Argusi. The relics were looted.

And so forth.

It’s interesting going back through these older articles now, in 2021, given the “official” WotC 5E adventures that have been published. “Dungeon of the Mad Mage” is kind of insanely long, and outside of Adventurers League I know of few groups willing to go through the entire thing. However, perhaps because of its size, DotMM uses a key format similar to the one you are laying out here. It also lays out info on the factions in each layer (some of which were in the original Undermountain materials in previous editions, some of which are new), and at the end of chapter on that layer it lays out the consequences or developments occurring depending on which faction (if any) the party helped out while navigating through the layer. I’m glad I bought it, even if I never run it, simply because it’s the cleanest and simplest dungeon/area keying system I’ve seen in an official D&D product.

probably about the 2014’s I was Converting B2 to 1EAD&D and instead of using subheaders and relying upon intuiting the necessary flow (which yes is a good skill to have) I went a trifle dogmatic by using the Excel cells to the right to present information on each subgroup I felt necessary (Eg: A1 would have room title and fluff, cell A2 would have Monster Data A3, would have Traps/Tricks/Secrets, A4 would have treasure, A5 would have Dm Notes, etc..