I just wrapped up my current thoughts on using cities in RPGs, so let’s take a moment and go back in time by a decade or so. In May 2002, I sent Bob Bledsaw a query letter for writing an updated version of the City-State of the Invincible Overlord. He sent me a polite, but somewhat vague, rejection. The reason for the vagueness became apparent a couple of months later when Necromancer Games announced their license to do exactly that thing. So I repackaged my proposal and shipped it over to Necromancer Games. I knew that was a longshot and wasn’t surprised when I got another polite rejection from Clark Peterson because they had their own plans for how to approach the material and a team already in place. I then filed it in a digital bin.

My goal was to be very faithful to the original, very minimalist key. But I also wanted to expand the material to make it more detailed and more useful. In order to demonstrate the approach I wanted to take, I adapted the entirety of Temple Street. (I would have supplied stat blocks for all the characters.) Perhaps you’ll find it of interest.

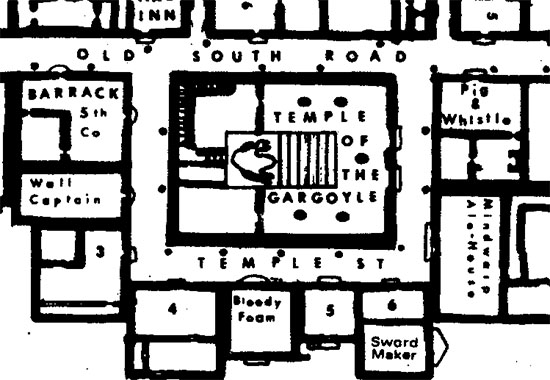

TEMPLE STREET

The broad cobbles of Temple Street were first laid down roughly five centuries ago as part of the broad, sweeping stone plaza which was set around the newly constructed Temple of the Flesh. Founded by a sect of Atlani cult worshippers, the Temple of the Flesh had been driven from their original site near the Square of the Gods by religious persecution. At the time the future site of Temple Street was an abandoned dirt track laying between the Wall and the South Road (which was, at the time, the southernmost boundary of the City State).

Over the course of the next three hundred years the Temple of the Flesh slowly waned, and as they did they were forced to give up more and more of their lands. Finally the Temple of the Flesh died out entirely, and the remnants of their once mighty stone plaza were refurnished into the modern Temple Street.

Despite the fact that it was abandoned, the former temple continued to dominate Temple Street. Various businesses and religions attempted to use the site, but mishaps and strange deaths seemed to plague anyone who came into possession of the property. A legend of a curse sprang up, and the property became totally dormant.

Then, roughly fifty years ago, it became apparent that the Temple had become occupied once again. Strange noises were heard emanating from the building, and shadowy figures were seen coming and going during the dark hours of the night. It is rumored that, although many brave souls entered the Temple to investigate, none ever returned.

Three years after this began, the Temple suddenly fell silent. Then, a few weeks later, a screed appeared on the Temple doors. Those who dared approach to read the parchment discovered that the long-deserted building had finally been claimed… by the Temple of the Gargoyle.

LOCATION: THE BLOODY FOAM

The Bloody Foam lies in the shadow of both the Temple and the Wall, drawing its primary custom from the militiamen of the 5th Company (whose barracks lie just up the street) and the heartier variety of wanderers passing through the City State – the type of wanderers who look for their drinking holes in the backwaters of whatever community they happen to be passing through. The Foam is owned and operated by Hangharid Goldenhand, a former adventurer himself.

The Foam’s dark interior is decorated in black oak, and typically lit by only a handful of murky lanterns and the bright flames which are perpetually kept stoked in the Foam’s massive fireplace. The resulting atmosphere is often foreboding to the newcomer, but welcoming to the regulars.

Upstairs, in addition to the quarters kept by Hangharid and his barkeep, are a number of rooms which are rented out (usually to one adventuring party or another). A back room is devoted to various games of chance.

CHARACTER: HANGHARID GOLDENHAND

Hangharid was once a hired fighter who travelled up and down the coast in the service of many different masters. Those days came to an end, however, when he lost his right hand (stories of how this happened, exactly, vary greatly – see sidebar text). Taking the small stash of wealth he had accumulated over the years, Hangharid bought a golden facsimile to replace his missing appendage, and spent the rest on the Bloody Foam.

The Foam’s previous owner had allowed the establishment to decay precipitously, but Hangharid performed a serious renovation, and when the Bloody Foam opened again he offered free drinks for a week to the militiamen of the 5th Company (whose barracks are only a block away, on Old South Road). By the time that week came to an end, Hangharid had earned himself a core of loyal customers who have come back, year after year.

Since opening the Bloody Foam, Hangharid has established himself as something of a community leader, and he seems to have a wide-ranging set of connections throughout the City State and beyond. Recently, regular patrons at the Foam have noticed that Hangharid has been visited regularly by strangers wearing finely embroidered green cloaks.

CHARACTER: COCKROACH BENGURD

Bengurd is the barkeep at the Bloody Foam. Rumor has it that he was once Hangharid’s torchbearer. Years later, when Hangharid heard that he had fallen down on his luck, he tracked him down and offered him a job. Bengurd gratefully accepted. Since then, Cockroach (apparently a nickname – but the only given name anyone seems to know him by) has become a fixture of the Bloody Foam.

CHARACTER: SEYLASHAHL

Seylashahl has been working at the Bloody Foam for a little over a year, and has quickly become the favorite barmaid of all the regulars – largely on the back of the amazing, and suggestively bawdy, juggling acts she works into her daily routines. Although she has strangely beautiful and alien features, no one is sure where she comes from.

Rumor: The Golden Hand

Hangharid never speaks of how he lost his hand, and this cavernous silence has been filled by a wide variety of tales, ranging from the mundane to the exotic. Some speak of a bet with a dark god which went awry; of torture at the hands of the Purple Claw; of strange traps buried beneath the surface of the earth. A few claim that the hand was lost in a drunken brawl. At the moment, however, the most popular tale tells of an audience with the Overlord and a secret mission to the catacombs beneath the city.

Perhaps the strangest rumors of all, though, are those that suggest that the hand itself has mystical powers – or is, in fact, a sentient creature in its own right. Although none claim to have ever seen any evidence of this, there are many who cast long and questioning stares at Hangharid’s golden fingers.

Rumor: Escape!

A group of militiamen who have just come off duty claim that a sabretooth tiger which escaped from the Overlord’s Zoo may be in the area. They warn that it is treason to harm a Zoo animal, but there may be a reward for anyone who can return the creature unharmed…

LOCATION: SEITERGUD’S SWORDS

Seitergud’s Swords is a small place, pretending to an opulence it does not possess: Pine has been painted to look like oak; faux-blue marble is inlaid upon the countertops. The proportions of the entire design are those of the dwarves – and although this makes the store somewhat uncomfortable to other customers, Seitergud seems to consider this a feature of sorts.

The store has earned a reputation within the underworld of the City State: Seitergud asks few questions, and his customers fewer.

CHARACTER: STEN SEITERGUD

Sten Seitergud was once a Royal Craftsman, in the service of Nordre Ironhelm, King of Thunderhold. Although a minor member of the royal guild, Seitergud labored faithfully for the better part of a century. Eighty years ago, however, he found himself on the wrong end of a political falling out within the royal court and was forced to flee for his life. He came to the City State, and quietly set up his own small business just within the city walls.

DWARVEN CRAFTSMEN

Over the years, Seitergud – still bitter over his own status as an outcast from his homeland – has served as a conduit for dwarves seeking to escape Thunderhold. Many of these political refugees only stay a few weeks before moving on, but some of those who have passed through his doors stay. At the moment four of his former kinsmen – Talen Mathalik, Yulthorn Wik, Veseb Dogin, and Baidan Suthok – serve as junior craftsmen in his shop.

Price List: Swords

| Short Sword | 10 gp |

| Longsword | 30 gp |

| Rapier | 10 gp |

| Falchion | 25 gp |

| Scimitar | 10 gp |

| Custom Made | +10-60 gp, 4-24 days |

Price List: Scabbards

| Leather | 1 gp |

| Iron | 3 gp |

| Silver | 5 gp |

| Gold | 50 gp |

Go to Part 2: Mindwarp Alehouse

For most of these settlements, you can probably treat the whole town as a single district: When the PCs encounter a small village or town in the hexcrawl, the expected interaction is to look around and figure out what useful information it’s supposed to give you (i.e., rumors about potential adventures to be found in the wilderness). Alternatively, maybe investigating the village will end up triggering a local adventure (i.e., the whole town has been replaced by dopplegangers). In either case, the urbancrawl investigation action provides a default method for interacting with settlements of all sizes, even if it’s only when the really big, important cities range into view – Greyhawk, City-State of the Invincible Overlord, Minas Tirith – that exploring the city neighborhood-by-neighborhood and street-by-street becomes an interesting adventure in its own right.

For most of these settlements, you can probably treat the whole town as a single district: When the PCs encounter a small village or town in the hexcrawl, the expected interaction is to look around and figure out what useful information it’s supposed to give you (i.e., rumors about potential adventures to be found in the wilderness). Alternatively, maybe investigating the village will end up triggering a local adventure (i.e., the whole town has been replaced by dopplegangers). In either case, the urbancrawl investigation action provides a default method for interacting with settlements of all sizes, even if it’s only when the really big, important cities range into view – Greyhawk, City-State of the Invincible Overlord, Minas Tirith – that exploring the city neighborhood-by-neighborhood and street-by-street becomes an interesting adventure in its own right.