I’m in a video!

Along with Chris Birch, we chat with our host Josh about some of the cool stuff that makes the Infinity RPG tick.

I’m in a video!

Along with Chris Birch, we chat with our host Josh about some of the cool stuff that makes the Infinity RPG tick.

First: Modiphius has released the Infinity Quickstart, which includes a streamlined version of the core mechanics, a general overview of the world, and six pregenerated characters so that you can pick it up and try the game out for yourself. The Quickstart is 100% free, so you really don’t have any excuse not to click the link and check it out.

Second: The Quickstart also includes an abridged version of the Paradiso Countdown, an introductory scenario that I wrote. The abridged version is nice, but the full version is even better. It’s going to be part of the Shadow Affairs campaign coming next year. But Modiphius is also offering access to the beta test version of the full adventure as an exclusive for backers of the Infinity kickstarter right now. So if you kick in just $1, you’ll be able to download the full adventure (which should provide 2-3 sessions of gaming). Check it out.

Third: There are now just 3 days left for the Infinity kickstarter! With the stretch goals we’ve been unlocking, the backers are getting some really fabulous deals. The PDF Master Level is currently delivering 13 books for £40 (approximately $60). The All the Books level at £300 is pricey, but you’ll get 22 books in both print and PDF plus a bunch of additional bonus material that’s already been unlocked.

Ash’s Guide to RPG Personality and Background is a fabulous template supported with rich random generators for creating rich RPG characters.

You start by defining Personality in four-ish steps:

Then you get the Background generator:

Although some of the entries (particularly the Professions) are slanted towards a fantasy setting, most of the material is pretty universal in its applicability. And although the depth of detail created by the template is obviously most useful for player characters, it’s pretty easy to raid it selectively as a GM to fill out elements of your NPC roleplaying templates.

Have you ever been running a published adventure, had the PCs encounter an NPC, and discovered that the NPC’s description was eight paragraphs of undifferentiated text? You remember reading through this stuff two days ago when you were reviewing the adventure, but how are you going to fish out all the little details from that wall of text? (And three scenes later, of course, you realize that everything has spun completely out of control because you forgot that the NPC was supposed to tell the PCs about the properties of the Starstone, but that was hidden away as a single sentence in the fourth paragraph. Whoops.)

Have you ever been running a published adventure, had the PCs encounter an NPC, and discovered that the NPC’s description was eight paragraphs of undifferentiated text? You remember reading through this stuff two days ago when you were reviewing the adventure, but how are you going to fish out all the little details from that wall of text? (And three scenes later, of course, you realize that everything has spun completely out of control because you forgot that the NPC was supposed to tell the PCs about the properties of the Starstone, but that was hidden away as a single sentence in the fourth paragraph. Whoops.)

Or have you been prepping your own material and found yourself wasting a lot of time writing up lengthy descriptions of your NPCs that never seem to have any real impact at the table? Are you trying to figure out a better way of organizing your NPCs so that you can just focus on the important stuff? (And so that, when your players decide to spontaneously visit the guy they met twelve sessions ago, you’ll be able to quickly pick that NPC up and start playing him again.)

Or maybe you’re really good at juggling all those little details, but you struggle when it comes to really getting into character or making each of your NPCs a unique, distinct, and memorable individual.

And maybe, as you’ve tried to find a solution for these problems, you’ve found various tools or techniques online or in How to GM books that are designed to give you richer and more evocative NPCs… but they all involve spending 5x longer prepping them.

Well, that’s what this Universal NPC Roleplaying Template is all about.

I’ve been using it for more than a decade now, slowly refining it through actual play. Generally speaking, it doesn’t take any extra effort compared to the traditional “wall of text” presentations, but it structures the NPC’s description into utilitarian categories that (a) focus your prep and (b) make it incredibly easy to use during actual play. I’ve found that I can design NPCs with this technique, lay them aside for months at a time, and then pick them back up again smoothly in the middle of play without any review: Instead of trying to parse several paragraphs of dense text, the template will guide you directly to the information that you need.

USING THE TEMPLATE

Name: Self-explanatory. (Or, at least, I hope it is.)

Appearance: Essentially a boxed text description that you can use when the PCs meet the the NPC for the first time. Get it pithy. 1-2 sentences is the sweet spot. Three sentences is pretty much the maximum length you should use unless there is something truly and outrageously unusual about the character. Remember that you don’t need to describe every single thing about them: Pick out their most interesting and unique features and let your players’ imaginations paint in the rest.

Quote: I don’t always use this entry, but a properly crafted quote can be a very effective way to quickly capture the NPC’s unique voice. Generally speaking, though, all you want is a single sentence. You should be able to basically glance at it and grok the voice. (Special exception if the character’s voice is “rambling old man”.)

Roleplaying: This is the heart of the template, but it should also be the shortest section. Two or three brief bullet points at most. You’re looking to identify the essential elements which will “unlock” the character for you.

There are no firm rules here, but I will always try to include at least one simple, physical action that you can perform while playing the character at the table. For example, maybe they tap their ear. Or are constantly wearing a creepy smile. Or they arch their eyebrow. Or they speak with a particular accent or affectation. Or they clap their hands and rub them together. Or snap their fingers and point at the person they’re talking to. Or make a point of taking a slow sip from their drink before responding to questions.

You don’t have to make a big deal of it and it usually won’t be something that you do constantly (that gets annoying), but this mannerism is your hook: You’ll find that you can quickly get back into the character by simply performing the mannerism. It will make your players remember the NPC as a distinct individual. And it can even make playing scenes with multiple NPCs easier to run (because you can use the mannerisms to clearly distinguish the characters you’re swapping between).

You’ll generally only need one mannerism. Maybe two. More than that and you lose the simple utility of the mannerism in unnecessary complexity. It’s not that the character’s entire personality is this one thing; it’s that the rest of the character’s personality will flow out of you whenever you hit that touchstone.

Round this out with personality traits and general attitude. Are they friendly? Hostile? Greedy? Ruthless? Is there a particular negotiating tactic they like? Will they always offer you a drink? Will they fly into a rage if insulted? But, again, keep it simple and to the point. You want to be able to glance at this section, process the information almost instantaneously, and start playing the character. You don’t need a full-blown psychological profile and, in fact, that would be counterproductive.

Background: This section is narrative in nature. You can let it breathe a bit more than the other sections if you’d like, but a little will still go a long way. I tend to think of this in terms of essential context and interesting anecdotes. Is it something that will directly influence the decisions they make? Is it information that the PCs are likely to discover about them? Is it an interesting story that the NPC might tell about themselves or (better yet) use as context for explaining something? Great. If it’s just a short story about some random person’s life that you’re writing for an audience of one, refocus your attention on prepping material that’s relevant to the players.

Key Info: In bullet point format, lay out the essential interaction or information that the PCs are supposed to get from the NPC. The nature of this section will vary depending on the scenario and the NPC’s role in it, but the most obvious example is a mystery scenario in which the NPC has a clue. Rather than burying that clue in the narrative of the NPC’s background, you’re yanking it and placing it in a list to make sure you don’t lose track of it during play. (The Three Clue Rule applies, of course, so just because something appears in this section it doesn’t mean that the PCs are automatically going to get it.)

You could also use this section to lay out the terms of employment being offered by the Mysterious Man in the Tavern. Or to list the discounts offered by a shopkeeper. It’s a flexible tool. In some cases, it might get quite long. But try to keep it well-organized (using the bullet points will help with that). If it just becomes a giant wall of text, its purpose has been lost.

Stat Block: If you need stats for the NPC, put ’em at the bottom of the briefing sheet in whatever format makes sense for the system you’re running.

DESIGN NOTES

Way back in 2001, Atlas Games published In the Belly of the Beast, a D20 adventure by Mike Mearls. This was a roleplaying-intense adventure featuring multiple factions trapped inside the belly of an immense demon. In and of itself, it’s a pretty awesome adventure. But it’s had a particularly enduring legacy for me because it contained the seeds of this NPC roleplaying template. Mearls broke his NPC information down into six sections: Key Information (which, in his version, was bullet points summarizing the character’s background), Quote, Background, Appearance, Roleplaying Notes, and Goals. The disadvantage of Mearls’ version is that it requires more prep work than the traditional method of prepping a character, but the basic idea of structuring the description of the NPC into utilitarian categories that were designed to be used at the gaming table was incredibly useful. (Like most good ideas, it seems simple enough… it’s just that nobody had done it before.)

I promptly absconded with it.

Over the years, I’ve refined the format and tightened its focus, developing it into a streamlined, universal template which I’ve found doesn’t take any extra effort to use, but which still brings all the benefits of the utilitarian structure. In that time I’ve used it in a wide variety of campaigns, and it’s proven itself to be a useful and flexible tool with a lot of different applications. (For example, check out the Muse to Your Left structure for Eclipse Phase games.)

EXAMPLE: BHALTAIR MCCLELLAN

Bhaltair McClellan is an NPC from Paradiso Countdown, an introductory adventure for the Infinity roleplaying game that you can currently snag if you’re a backer of the game’s kickstarter.

Appearance: A boisterous, round-bellied man with thick red hair that tumbles down into a beard that threatens (but does not quite succumb to) unruly excess.

Quote: “You should take a load off, mate. And have a drink. It won’t bring him back, but it’ll keep us all sane.”

Roleplaying:

Background: Bhaltair is Ariadnan of Caledonian stock. When he was just a young kid, his father went off to fight in a bloody frontier conflict between Caledonia and Rodina. He never came back. Bhaltair made a pledge that he would work to never see his homeworld torn apart by such senseless violence again. He became a politician and quickly discovered how difficult the dream of peace can be. When the Human Sphere returned to Ariadna, he was at first overjoyed at how it unified the planet…and then watched in horror as the Commercial Conflicts ripped his planet apart again. He lost himself in drink for a time and then, concluding that the only way to bring true peace to Ariadna was to solve the off-planet problems that were manifesting themselves there, he became a diplomat. He did not participate in the negotiation of the Tohaa Contact Treaty, but he has recently arrived to take part in the Alliance Summit.

Key Info:

EXAMPLE: SYR ARION

Syr Arion appears in City Supplement 1: Dweredell.

Appearance: Arion is still a man in the flush of youth: Short-cropped, jet black hair sets off his piercing blue eyes. His frame is only lightly muscled, but toned and trained. The weight of his office, however, has brought bags beneath his eyes. And the late hours his sense of responsibility brings often causes his shoulders to stoop with exhaustion. But when the Syr gathers his strength, the image of a great man remains.

Quote: “Just give me time to think. There must be a way.”

Roleplaying:

Background: Arion’s mother died in childbirth, and he was reared as the last child of the Erradons by his father, a man whose faculties were already deserting him when Arion was born. Arion’s father believed that his brother had been killed by the Guild, and the one edict he never wavered from was that Arion should be strictly sequestered. As a result, the only true friend Arion had while growing up was Celadon, the Captain of the Prince’s Guard – a man thirty years his senior.

Despite this, or perhaps because of it, Arion dedicated himself to rigorous self-perfection: When he was not learning swordplay from Celadon, he was spending hours pouring over the musty tomes of his father’s library. He saw that his father was a poor ruler, and believed it was his place to restore the honor of the Erradons by restoring the glory of Dweredell.

EXAMPLE: DEVOLA THE NAGAINA

Devola is a character from The Devil’s Spine, a campaign for Monte Cook’s Numenera. I adapted her into this format when I was running the campaign. My local players should skip this section, since I’m hoping to run this campaign again in the future.

Appearance: A massive serpent, 50 to 70 feet long. Her mouth is surrounded by tentacles 15 feet long, most of which have been adapted so that they end in cybernetic or bioengineered tools, syringes, or weapons.

Roleplaying:

Background: Devola is a scientist of sorts, specializing in surgical experimentation and evolutionary biology. She is far more learned in her chosen areas of expertise and far more intelligent than the vast majority of Ninth World humans.

Key Info:

ADDITIONAL READING

Advanced NPC Roleplaying Templates

Quick NPC Roleplaying Template

Spell Component Roleplaying

Many people are familiar with the 5 Room Dungeon. It’s a simple little structure that you can very quickly pour content into, allowing you to create simple dungeon scenarios on the fly. Basically you design a dungeon with 5 rooms, and in those rooms you place:

Depending on the system you’re using and exactly what you stock each room with, this should produce about 2-4 hours of game play.

Personally, I’m not a huge fan of the 5 Room Dungeon: Partially because its structure is too rigid (which results in effective material, but also very predictable material if you use it too frequently). And partially because a remarkable number of people preach it as the one-true-way of dungeon design (which isn’t really the fault of the structure itself, but combines rather horribly with the first problem).

But what the 5 Room Dungeon does a very good job of demonstrating is how valuable it can be to have a simple structure like this in your back pocket. Not only does it let you very quickly (and very effectively) prep simple scenarios, it’s also incredibly useful when you need to start improvising during a session: You can very quickly brainstorm ideas, paste them into the proven scenario structure, and know that the result is, on a basic level, going to work.

I’ve got a similar structure that I default to whenever I’m looking to whip up something simple and quick. I’ve come to call it…

THE 5 NODE MYSTERY

The 5 Node Mystery structure arose pretty much completely independently from the 5 Room Dungeon, but the repetition of the number 5 isn’t really coincidence: Five good, meaty chunks of interactive material is pretty much what you need to fill an evening of gaming. The interaction between five different elements is also roughly the bare minimum complexity required to create something more meaningful than a solitary random encounter. Nothing wrong with a random encounter, of course, but if you’re looking for the next step up — if, for example, you’re interested in what the random encounter might lead to — then this is basically what you’re looking for.

You use the 5 Node Mystery when you want a simple, fairly straight-forward investigation. It uses node-based scenario design and it works like this:

1. Figure out what the mystery is about. Was someone murdered? Was something stolen? Who did it? Why did they do it?

2. What’s the hook? How do the PCs become aware that there’s a mystery to be solved? If it’s a crime, this will usually be the scene of the crime. It could also be “place where weird shit is happening”. Or maybe someone or something comes to the PCs and brings the mystery with them. (Thugs kicking down the door is a classic.)

3. What’s the conclusion? Where do they learn the ultimate answers and/or get into a big fight with the bad guy? (Big fights with bad guys are a really easy way to manufacture a satisfying conclusion.) This will be your Node E.

4. Brainstorm three cool locations or people related to the mystery. Ex-wife of the bad guy? Drug den filled with werewolves? Stone circle that serves as a teleport gate? These will be your Nodes B, C, and D. (Hint: Brainstorm more than three items. Then pick the three coolest ideas. You’ll end up with better stuff. Also: Before you toss the other ideas, see if there’s any way that you can combine them with the three you picked and make them even cooler.)

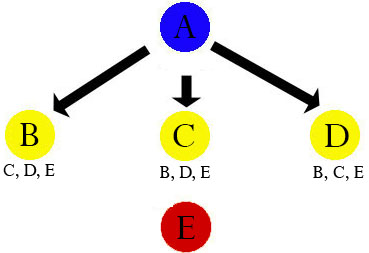

5. You’ve got five nodes. Connect ’em with clues. The default structure looks like this:

The basic idea here is that Node A points you in three different directions (although, remember, the PCs might find only one of the clues). Then those three locations point to each other and also point towards the big conclusion. Simple.

You’ll also find that the precise structure of the 5 Node Mystery is easy to modify on the fly. In some cases, you’ll find that the nature of the scenario will pretty much dictate the pattern of the clues. (For example, while working on the Violet Spiral Gambit — which was designed in a few hours using this structure — I discovered that it made more sense for the initial node to point to two locations and then have those two locations point to a third. Then I loaded up that third location with a bunch of different clues all pointing to the conclusion.) About the only thing you should avoid as a general rule are clues pointing directly from Node A to your conclusion.

There is a possibility in this structure, of course, for the PCs to go from Node A to Node B to Node E (skipping Nodes C and D). In some cases, the scenario will be modular enough that this just means the conclusion isn’t what you thought it was. (You thought the conclusion was a big showdown with a bad guy in the violet tower at the center of the graveyard. Turns out, it was actually a rooftop chase as the badly injured PCs try to escape the werewolves from the drug den.) In other cases, the nodes left behind the PCs will metastasize into new adventures — either because the werewolves end up causing trouble or because when the PCs go back to mop-up the werewolves they’ll find clues pointing them to other scenarios.

THE 5 x 5 NODE CAMPAIGN

Seasoning your scenario with clues pointing to other scenarios is actually a pretty good way to start expanding from 5 Node Mysteries into designing more interwoven campaigns.

1. Design five 5 Node Mysteries. You might have some idea about how they all relate to each other as you’re designing them, but maybe not. Discovering how seemingly unrelated things are actually connected to each other is a great way to make both things richer and more interesting.

2. Arrange the 5 Mysteries into the same node pattern. In other words, Mystery A will have clues pointing to Mysteries B, C, and D. Mystery B will have clues pointing to Mysteries C, D, and E. And so forth. (If you didn’t already know how the mysteries related to each other, the process of figuring out how clues for Mystery D ended up over in Mystery B is the part where you’re going to figure that out.)

As you’re seeding your clues into each mystery, mix it up a bit. Some clues will be the “pay-off” for solving the first mystery: You’ve taken out El Pajarero, but who was he really working for?! But don’t fall into the trap of always putting the clues in the concluding node. Spread ’em around a bit.

And that’s basically it. It’s a very simple technique for you to use, but you’ll find that (much like the technique of the second track) it creates experiences for your players which are complicated, interesting, and ornate.

FURTHER READING

Game Structures

Node-Based Scenario Design

Gamemastery 101