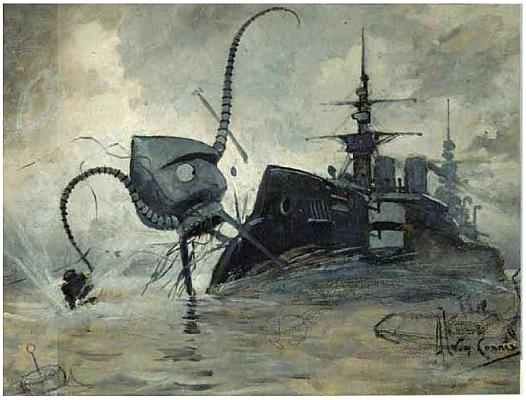

October 1st is Dave Arneson Day, a celebration of the Father of Roleplaying Games on the day of his birth. After writing up Reactions to OD&D: The Arnesonian Dungeon, I decided that I wanted to celebrate Dave Arneson Day this year by running Castle Blackmoor. And I specifically wanted to do so in a way which would closely emulate the feel of that very first session when Arneson’s players walked into the basement, discovered Castle Blackmoor, and ventured down the stairs into the dungeons beneath it.

I relatively quickly decided on a few mission parameters for this endeavor.

First, I wasn’t interested in trying to re-engineer the original rules Arneson used, if for no other reason than that this is, in fact, flatly impossible. Arneson kept no records of those rules, he never shared them with anyone (including the players), he redesigned them so often that I doubt even he remembered what the original rules were by 1973, and I’ve already done the “explore mysterious ur-text mechanics and cobble a game out of them” thing (see Reactions to OD&D).

Second, my specific point of interest was the way in which Arneson organically created the dungeon; i.e., the game structures he used for stocking and re-stocking the dungeon. As described in The Arnesonian Dungeon this is something that we’re able to tease out of the surviving record with a fair amount of detail (if not necessarily the specific charts and so forth).

Third, my interest in exploring the established canon of Blackmoor was fairly minimal. This can be a fascinating topic (although frustratingly scant; so many players, but very few memories, and the memories that have been recorded often contradict each other and the written records), but Blackmoor was (and arguably is) a living campaign with 40+ years of history which has been inconsistently reflected in disparate printed sources. Rather than enmeshing myself in that sort of Byzantine continuity, what I was interested in was creatively positioning myself in the same place Dave Arneson creatively positioned himself on Day 1 of the Blackmoor Dungeons and then moving forward from there.

What did this approach mean in practice?

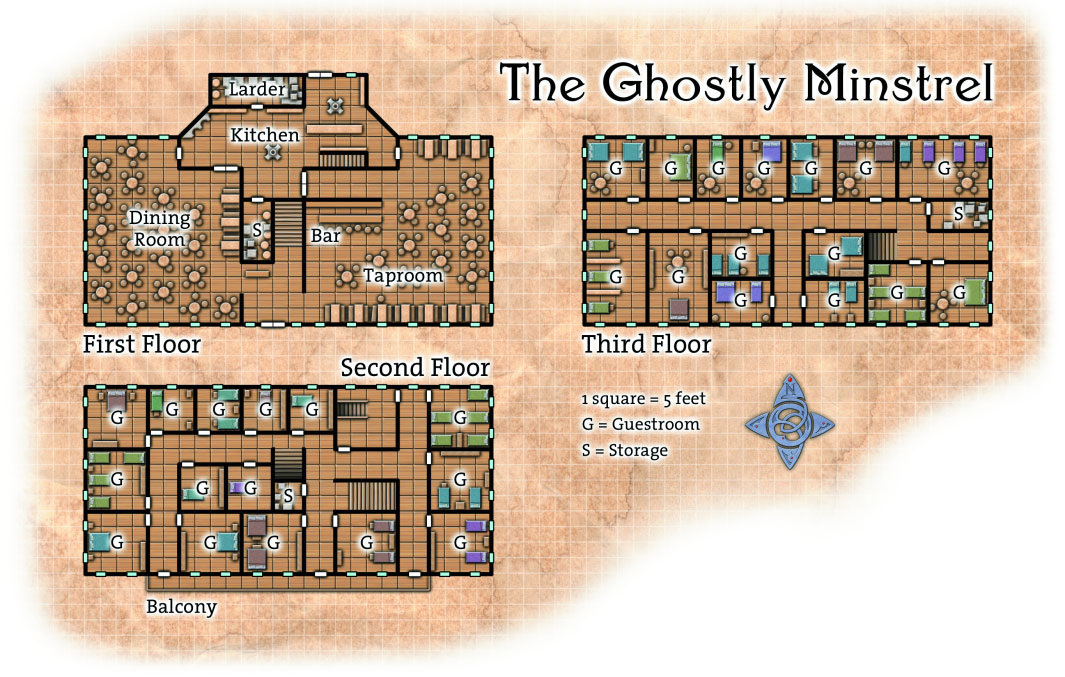

- Take the original maps of the dungeon as presented in the First Fantasy Campaign.

- Recreate the original monster and treasure stocking tables to the best of our ability, then use them to stock the maps.

- Establish a minimal baseline of “established lore”, largely based on the material in the First Fantasy Campaign.

- Set up a scenario reminiscent of Greg Svenson’s recollection of The First Dungeon Adventure.

- Run the game using just the original three OD&D booklets.

I want to be quite clear here and reiterate that my goal is not to perfectly recreate Arneson’s original dungeon key. Or even to take the limited information we know about that dungeon key and then fill in the holes around those fragments. For example, the fact that I haven’t put 2 Lycanthropes in Area 18 of the 8th Level (as found in the FFC key) is not a mistake; that’s simply not what I’m trying to do here.

I was rather hoping to have all of this prepared for public presentation several weeks ago so that others could also use it for Dave Arneson Day this year. Unfortunately, I ended up going down a few too many rabbit holes with my research. (And, as I write this, I’m still trying to figure out to exactly what degree I want to rely strictly on the maps from the First Fantasy Campaign and to what degree I want to avail myself of other efforts to correct shortcomings and inaccuracies in those maps.) Hopefully you will still find it of interest, and perhaps some of you will find some other occasion for using this material.

If nothing else, there’s always next year, right?

STOCKING THE DUNGEON

STEP 1: CHECK FOR INHABITED ROOMS

- 1st Level: 1 in 6

- 2nd Level: 2 in 6

- 3rd+ Level: 3 in 6

STEP 2: DETERMINE PROTECTION POINTS

- Roll 1d10 and multiply by the level’s protection factor.

| LEVEL | PROTECTION FACTOR |

|---|---|

| 1st Level | 5 points |

| 2nd Level | 10 points |

| 3rd Level | 15 points |

| 4th Level | 25 points |

| 5th Level | 35 points |

| 6th Level | 40 points |

| 7th Level | 50 points |

STEP 3: ROLL ON MONSTER LEVEL TABLES

Simple Option: Once a creature type is determined, purchase the maximum number of creatures allowed by your protection point budget (minimum 1).

Complex Option: Roll Number Appearing on the OD&D monster tables. (This is indicated on the monster level tables for ease of reference.)

- Purchase as many monsters of that type as your protection point budget allows up to the Number Appearing generated (minimum 1).

- If you run out of Protection Points before hitting the Number Appearing and have points left over, purchase a weak version of the same creature (baby, etc.).

- If you purchase the full Number Appearing and have Protection Points left over, roll again on the monster level table to create a mixed encounter.

STEP 4: GENERATE TREASURE

Determine Presence of Treasure: 3 in 6 chance for occupied rooms; 1 in 6 chance in unoccupied rooms.

Determine Treasure Type

| D6 | TREASURE TYPE |

|---|---|

| 1-2 | Gold |

| 3 | Potions & Amulets |

| 4 | Arms & Armor |

| 5 | Equipment |

| 6 | Roll Again Twice (Stacks) |

MONSTER LEVEL TABLES

Use:

- Group I for 1st and 2nd dungeon level

- Group II for 3rd and 4th dungeon level

- Group III for 5th+ dungeon level

GROUP I

| D10 | MONSTER | # APPEARING | POINT COST |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Orc | 30-300 | 2 |

| 2 | Elf / Fairy | 30-300 | 4 |

| 3 | Dwarf | 40-400 | 2 |

| 4 | Gnome | 40-400 | 2 |

| 5 | Goblin / Kobold | 40-400 | 1.5 |

| 6 | Sprite / Pixie | 10-100 | 4 |

| 7 | Hobbit | 30-300 | 1.5 |

| 8 | Giant Spider | 1-10 | 15 |

| 9 | |||

| 10 | |||

GROUP II

| D10 | MONSTER | # APPEARING | POINT COST |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||

| 2 | Lycanthrope (Wolf 1-2, Lion 3-4, Bear 5-6) | 2-20 | 20 |

| 3 | Fighting Man (Level = Dungeon Level) | 30-300 | 10 * Level |

| 4 | Wizard (Level = Dungeon Level) | 30-300 | 10 * Level |

| 5 | Roc / Tarn | 1-20 | 20 |

| 6 | Troll / Ogre | 3-18 | 15 |

| 7 | Ghoul | 2-24 | 10 |

| 8 | Gargoyle | 2-24 | 15 |

| 9 | |||

| 10 | |||

GROUP III

| D10 | MONSTER | # APPEARING | POINT COST |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||

| 2 | Balrog* | 1-6 | 75 |

| 3 | Dragon / Purple Worm | 1-4 | 100 |

| 4 | Elemental (Air 1-2, Earth 3-4, Water 5, Fire 6) | 1 | 100 |

| 5 | Ent | 2-20 | 15 |

| 6 | Giant | 1-8 | 50 |

| 7 | True Troll | 2-12 | 75 |

| 8 | Wraith (Nazgul) | 2-16 | 10 |

| 9-10 | |||

* 2 in 6 chance the Balrog is guarding something (60% magical, 40% wealth).

Hobbit: Use kobold stats.

Giant Spider: Use Ogre stats, with a poison that deals full damage a second time on failed save.

DESIGN NOTES

Castle Blackmoor’s dungeons descend to Level 10 in the printed maps. (Reputedly only one expedition ever discovered the 11th Level, but the dungeons were said by Arneson to go as far down as the lava pits on the 25th level.) Despite this, the Protection Factor table ends at 7th Level because that’s as far as Arneson provided information. Beyond 7th level the value would have either capped or continued to increase. (But you run into additional problems in any case in the lack of Group IV monsters.)

I’ve used the OD&D # appearing entries here out of a sense of purity, although due to the “generate a tribe” mentality of those numbers they largely negate the point for the Group I creatures. You might consider ripping them out and replacing them with more dungeon-appropriate numbers (perhaps sourced from a later edition). The complex method utilizing the # Appearing entry is not strictly Arnesonian in any case. Use to taste..

RUNNING CASTLE BLACKMOOR

Part 2: Special Monsters

Part 3: Treasure Stocking

Part 4: Magic Swords

Part 5: Castle Background & Features

Part 6: The Dungeon Key

Part 7: Restocking the Dungeon

Part 8: Special Interest Experience

Part 9: Special Interests

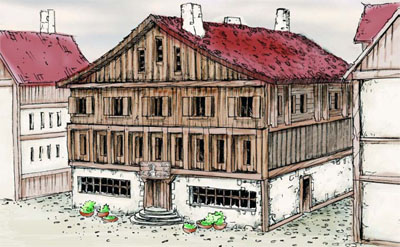

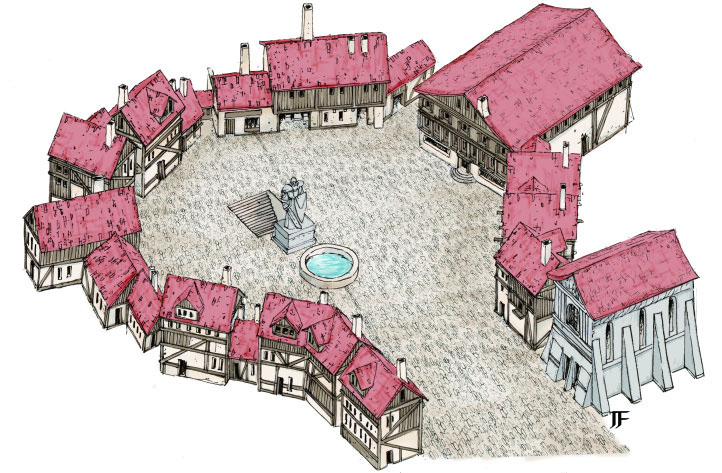

Part 10: Blackmoor Village Map

Part 11: Blackmoor Player’s Reference

Part 12: Lessons Learned in Blackmoor

Reactions to OD&D: The Arnesonian Dungeon

Reactions to OD&D: Arneson’s Machines