Let’s imagine that your players are in the city of Dweredell and they need to go to the village of Maernath to study the ancient crypt of the founder of the Verdigris Order.

How does that trip play out at the table?

The first option is the easiest: Skip it. Look at your map to figure out the distance between Dweredell and Maernath, consult a table of wilderness travel speeds to calculate how long the trip will take, and then say, “Okay, having journeyed northeast across the Viridwold, a week later you arrive in Maernath.”

There’s nothing wrong with this approach. In many cases, it will be exactly the right way to handle travel. Following the precepts of The Art of Pacing, you’ve determined that there are no interesting choices to be made during the journey and so you’re framing past that empty time to the next set of interesting choices.

But often you’ll reflect on this and feel vaguely unsatisfied. Perhaps you’ll think of any number of fantasy stories you’ve read in which the act of journeying from one location to another is a significant feature of the narrative and feel like you’re missing out on an opportunity. (These stories aren’t limited to fiction, either. Xenophon’s March of the 10,000 would be really boring if the Anabasis was just, “We left Cunaxa and, long story short, we were back in Greece two years later.”)

This line of thought — “Something should happen on the road to Maernath…” — often leads to some variation of Vaarsuvius’ Law of Random Road Encounters:

Of course, this still feels a trifle unsatisfying. You can see this in the expression of the “law” itself: Rather than being an awesome part of your game, the random road encounter feels like some sort of obligation.

(I will also briefly channel my grumpy grognard long enough to point out that if you’re handling random encounters properly they should be neither tedious nor a waste of time, but that’s a separate topic.)

Nevertheless, it feels like you could be doing more.

TRAVEL BY HEXCRAWL

At this point, with the rise of the Old School Renaissance, you may have heard about hexcrawling. That’s supposed to be a method for handling the wilderness in your campaign, right? So obviously the solution to your lackluster travel scenario is to build it as a hexcrawl.

I’ve written a whole series about how hexcrawls work, but the basic version is that you draw the wilderness as a hexmap, key each hex on the map with interesting content, and then trigger the content when the PCs enter the hex. The hexcrawl structure is primarily designed to support exploration, and if you’re prepping a single journey from Point A to Point B it is not the structure you want to use.

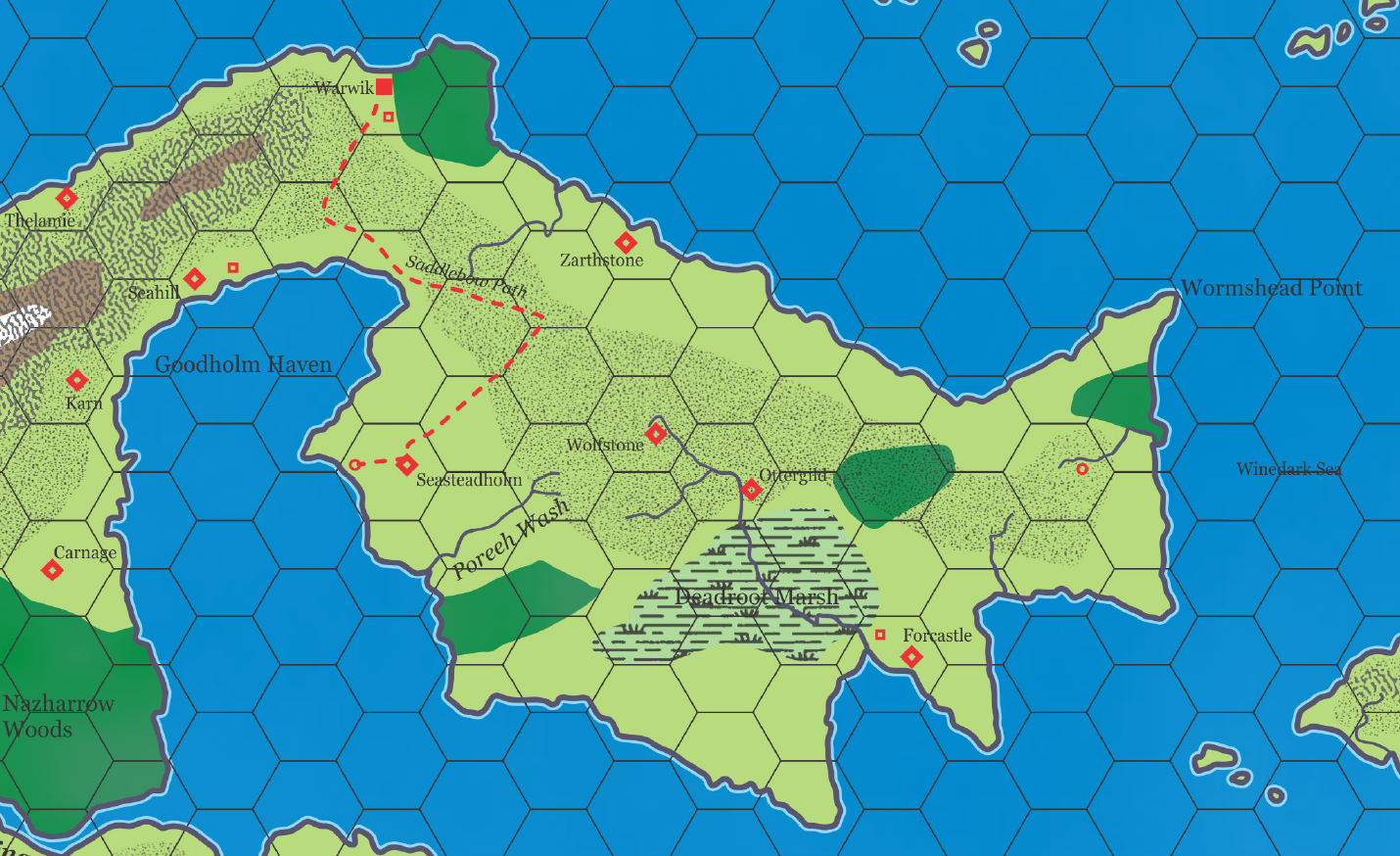

To demonstrate why, consider this hexmap from the Wilderlands of High Fantasy and imagine that your PCs want to take a trip from Warwik to Forcastle:

In order to prep that chunk of map as a proper hexcrawl, you would need to key every hex on the map. If you limited yourself to just the main peninsula of land shown here, that would mean prepping more than forty hexes of content. As the PCs journey from Warik to Forcastle, however, they would only visit a fraction of these hexes. In other words, you’ll end up prepping a lot of content that will never be used.

It’s clear that this is not an efficient way of prepping a specific journey through the wilderness, and it touches on a more fundamental truth, which is that the prep load for a hexcrawl really only makes sense if you’re going to be re-engaging with the same patch of wilderness dozens of times.

(This is trivial to achieve with an open table, where you can have dozens of players and characters traipsing across the same chunk of the world, but can be more difficult in a dedicated campaign with a single group of characters.)

The obvious rejoinder here is that you could theoretically prep this hexcrawl without prepping content for all these hexes. You could instead focus only on the hexes the PCs are likely to pass through. For example, in a journey from Warwik to Forcastle it’s relatively unlikely that they’ll end up at Wormshead Point.

BASIC TRAVEL ROUTES

As you begin zooming in on the most likely paths that the PCs could take from Point A to Point B, however, you’ll quickly discover that the hexcrawl structure itself is filled with procedures that become irrelevant if the PCs are following a predetermined route. What we really want is a structure dedicated to route-based travel that can focus our prep and be run efficiently at the table.

CHOOSE YOUR ROUTE: When beginning a new journey, the first thing the PCs must do is choose which route they’re going to use. This choice is only possible, of course, if the PCs are aware of what routes they can use to get where they’re going. They might gain that information from things like:

- Maps

- Local guides

- Mystical assistance

- Personal experience

If the PCs don’t know of any routes from where they are to where they want to go (and can’t find one before departing), then what they’re actually doing is exploring and you can default back to hexcrawling or a similar structure.

In order for the choice of routes to be interesting, there must be some meaningful distinction between the routes. “Meaningful” in this case means that it’s something the PCs care about. Common distinctions include:

- Speed. One route is faster than the other. (You will always need to calculate how long each route will take.)

- Difficulty. One route is more difficult to navigate. It might require special knowledge, special tools, or special skills to successfully traverse. (Climbing through the mountains or being able to answer the riddle of the gate-sphinx.)

- Stealth. One route will make it easier for the PCs to avoid detection. This can either be in general or a particular route might make it more difficult for one specific NPC or faction to detect them. (You can also conceptually invert this and instead think of it as a route making you vulnerable to detection from a particular faction: If you take the High Road you might be pressganged by the king’s army. The army’s recruiters don’t go into the Bloodfens, but if you go that way you’ll be at risk from the goblin rovers.)

- Expense. The cost of traveling the route. (This can be as simple as the price of a ticket.)

- Advantageous Landmarks. A route can have beneficial pitstops long the way, making it potentially more appealing than other options. (Visiting the Oracle of Delphi or seeing an old friend.)

- Hazards. Conversely, there might be a significant hazard along one of the routes. (You can enter Mordor this way, but you’ll have to figure out some way past Minas Morgul.)

In order for this to be a choice rather than a calculation, you’ll want to have the routes distinguished by at least two incomparable characteristics.

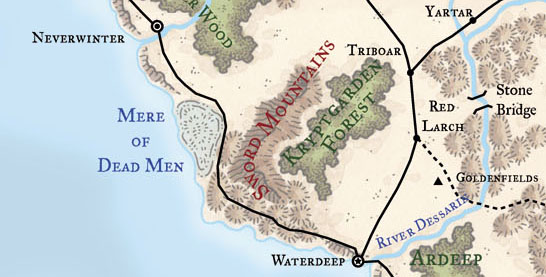

For example, consider a journey from Waterdeep to Neverwinter.

You look at the map and say, “You can take the High Road or you can travel by sea.”

“What’s the difference?” they ask.

“Well,” you say, “You’ll get there faster by sea.”

This is not a choice. It’s a simple calculation: The routes are identical except for the speed with which they’ll get you to Neverwinter, and so you take the route which is faster.

But if you instead say, “Well, it’s faster to sail, but there are reports of Moonshae pirates hitting ships along the coast,” this is no longer a simple calculation. The PCs have to choose whether speed or safety is more important to them.

One solid set of incomparable distinctions is all you need for this to work, but you can always add more (and you will generally find them arising naturalistically out of the given circumstances of the game world). Watch out, though, for inadvertently turning the choice back into a calculation as you add complexity. For example, you might say:

- The sea route is faster and is dangerous due to pirates.

- The road is dangerous due to the hazards of the Mere of Dead Men.

If the pirates and the restless undead of the mere are known to be equally hazardous, then you’re back to a straight-up calculation: There’s equal danger on both routes and one route is faster.

(This doesn’t happen if the PCs can’t be sure of the relative hazard posed by the pirates and undead. In that scenario it becomes an incomplete information problem. This is one of the subtle ways in which My Precious Encounter™ and similar design methodologies that always adjust the difficulty of the game world to the level of the PCs so that all challenges are identical degrade the depth of play. It creates a meta which eliminates incomplete information problems. But I digress.)

This is also why the PCs have to care about the distinction between routes. If speed isn’t actually important to them (they need to be there before June and either route will get them there by April), then Faster + Hazardous vs. Slower + Safer is still just a calculation, this time of which route is safer.

Don’t feel like you need to create stuff to make a particular route a viable choice, though. Just recognize that it’s not a choice and don’t present it as such (or explain why it isn’t if that’s relevant). For example, if you’re trying to get from Chicago to Indianapolis, you wouldn’t consider “first drive to St. Louis, then turn around and drive back to Indianapolis” as an option. (Because why would you?)

TRAVELING THE ROUTE: You’ll want to break the journey into a number of turns. I recommend multiple turns per day (so that it’s possible to have more than one encounter per day), and if you’re also doing hexcrawling in the campaign I recommend using the same timekeeping. (This consistency will make it easy to swap back and forth between the two travel structures. More on that later.) If we were using my structure for hexcrawls, this would mean six watches per day (two of which would generally be spent travelling and four resting).

There are three things you’re tracking as part of your procedure:

- Landmarks. A route is fundamentally defined by the sequence of landmarks that are spaced along its length. This might be permanent structures (cities, statues, etc.) or they might be programmed encounters that only apply to this specific journey (a broken down wagon, an ambush by goblin rovers, etc.), but either way they’ll be encountered at specific points along the route.

- Random Encounters. If you’re designing an encounter table specifically for the journey, I recommend keeping it pretty simple unless you’re planning to use this route repeatedly.

- Resources Used. Food, water, etc. This is optional, and there are many types of trips in which it won’t be relevant. (For example, if food and board are included in the price of your ticket.)

What about distance traveled? If you’re familiar with my hexcrawl structure (and many others), you’ll know that a key part of the procedure is determining exactly how far people have traveled each day. When traveling by routes, though, this is unnecessary because this is built into the design of the route: You know the total time it will take to traverse the route, you know at which times along the route you’ll encounter landmarks, and travel along most types of routes will generally be far more predictable and consistent than traipsing through the wilderness. (At a meta-level, variable travel distance creates an additional variable that complicates mapping and navigation in wilderness exploration. This is largely irrelevant if you’re traveling along a known route, which is another reason to ignore it.)

If the PCs take actions which vary the speed of their travel, you can apply those modifiers directly to the route timetable. If you really want to do the simulation of variable distance traveled per day (and there are scenarios in which this could easily be relevant), then it’s fairly easy to add this into your procedures.

On that note, let’s talk about additional features and levels of complexity that you can add to this basic, streamlined structure.