The PCs’ goal in Avernus is to free Elturel, and this requires three things:

- Bellandi’s pact with Zariel must be broken.

- The chains holding Elturel must be severed.

- Elturel must be returned to the Material Plane.

Of these, the essential modus operandi is the first: For most of their time in Avernus, the PCs can be strictly motivated by figuring out how to break the pact and the campaign will keep ticking along happily. In fact, it’s theoretically possible for them to actually destroy the contract only for them to then realize that, pact or no pact, Elturel is still physically stuck in Hell.

BREAKING THE PACT: There are three ways to break Bellandi’s pact.

- Both copies of the infernal contract must be brought together and then destroyed. Destruction requires special effort, such as dipping the contracts in the River Styx, the fires of an ancient dragon (perhaps Tiamat?), or a wish

- If Zariel is redeemed, she will cancel all of her infernal contracts.

- If Zariel is killed, all of her infernal contracts are canceled.

SEVERING THE CHAINS: The chains holding Elturel can be severed before the infernal contract is broken, but they will simply reform. They are a metaphysical manifestation of the contract and become physically severable only when the contract no longer exists. They can be severed in four ways.

- Zariel could do it with or without the Sword (because it was her pact which formed them).

- The PCs could form an alliance with a powerhouse (Bel, Tiamat, or a released Gargauth; but not the planetar or any holy power other than a redeemed Zariel for metaphysical reasons).

- The Sword of Zariel can cut the chains.

- There is a control room for the Dock of Fallen Cities in Zariel’s Flying Fortress, which can be used to release the chains.

RETURNING ELTUREL: If the PCs break the contract and sever the chains, then Elturel is left floating above the plains of Avernus. Now what? Moving an entire city through planar space is a non-trivial task, that’s why Zariel bathed the city in the Companion’s light for fifty years in order to build up an etheric charge (see Part 4B).

Good news, though: When that negative charge was reversed to generate the energy wave that brought Elturel to Avernus, an equal and opposite charge was passed into the Companion. (That’s the reason it’s been crackling with lightning this whole time.) This means that if the planetar inside the Companion is released, it will be able to literally lift the entire city out of the Nine Hells and return it to the Material Plane.

- The PCs can release the planetar by retrieving the adamantine key rods.

- A redeemed Zariel can also do so.

ALTERNATIVE – GATE ESCAPE: Once Bellandi’s pact has been broken and the chains severed, it becomes possible to evacuate Elturel. (Prior to that, anyone who was in Elturel when it was brought to Avernus is bound and cannot leave the Nine Hells.) We’ll be seeding a few options for opening long-term gates that last long enough for thousands of people to pass through them into Part 7; it’s also possible that the PCs might be able to convince powerful allies (like Tiamat or Bel) to do the same.

A full-scale evacuation option, however, is a corner case I’m not going to spend time prepping unless the players jump for it. The particulars of the evacuation will depend a lot on current circumstances. Things to think about:

- How can the PCs make sure everyone in Elturel knows about the evacuation?

- Who might attempt to stop the evacuation? (Zariel launching a full-fledged devil invasion of Elturel to prevent her prizes from escaping is definitely an option at this point.)

- How will the PCs protect the gate?

- What other problems, roadblocks, and catastrophes might afflict the evacuation effort?

- What factions can help the PCs (and how)?

- What ethical quandaries need to be resolved? (For example, who gets to go first? And should some people be allowed to go at all? Some factions might not want High Rider Ikaia and his vampiric spawn coming with them.)

To make things really epic, remember that we’ve set up the metaphysics so that it’s literally the good souls in Elturel which keep the city floating above the Avernian plains. Although in this scenario the chains are no longer dragging the city down, if those souls literally leave, the whole city could begin rapidly falling. Imagine:

- A final siege upon the gate’s position by Zariel.

- One whole half of the city cracks loose and falls into the Styx below.

- The PCs desperately trying to get the last few thousand people through the gate as the ground begins to crack and crumble around them!

BARGAINING WITH ZARIEL

Things an unredeemed Zariel could potentially do:

- Give the PCs her copy of the Bellandi pact.

- Cancel the Bellandi pact outright.

- Sever or release the chains holding Elturel.

- Release the planetar from inside the Companion.

The only thing Zariel is willing to trade for is the Sword of Zariel. (The published adventure suggests a couple other possibilities, but given the scope of what Zariel is giving up — a plan 50+ years in the making and tens of thousands of new foot soldiers for her armies — it’s really difficult justifying any of them.)

I further recommend that, by default, Zariel will only trade the Sword for the physical contract itself. (Primarily because the special effort still needed to destroy the paired contracts is more interesting than just having Zariel do it herself.) Smart PCs will make sure the bargain includes a provision that Zariel won’t send a task force of devils to steal the contracts back from them.

If the PCs can sweeten the deal (giving her the Shield of the Hidden Lord, agreeing to kill one of her enemies, etc.) they might be able to get her to cancel the contract outright or sever the chains, too.

REDEEMING ZARIEL

As we’ll discuss more in Part 6D, the Sword of Zariel contains a literal spark of goodness: Zariel placed a shard of her own soul in the Sword deliberately, knowing that the devils were coming for her and sensing her own weakness. The Sword will thus offer the PCs an opportunity to redeem Zariel if they have the chance.

If Zariel is redeemed, she can (and will):

- Cancel all of her infernal contracts.

- Sever the chains holding Elturel.

- Release the planetar.

This is more or less the “official” or “best” ending of Descent Into Avernus. If the PCs can pull off the redemption, they pretty much solve the whole problem in one fell swoop.

ALTERNATIVE – DREAM MACHINE REDEMPTION: As an alternative to the Sword of Zariel, it might also be possible to redeem Zariel by somehow maneuvering her into the dream machine with Lulu, forcing her to relive her memories, and, thus, giving her the opportunity to make a different choice.

This seems like a pretty long shot. But if one of the players make a 1,000 IQ play and they somehow manage to pull it off, more power to them. (Knocking Zariel unconscious and literally dragging her into the machine is one way. In her hubris, she’d probably also be willing to agree to get into the dream machine for a price considerably lower than the Sword of Zariel.)

RAID ON THE FLYING FORTRESS

In Part 7D, I’ll be redesigning Zariel’s Flying Fortress using the Raiding the Death Star! scenario structure. There are two things the PCs can gain by raiding the  fortress:

fortress:

- Zariel’s half of Bellandi’s contract.

- Access to the control room for the Dock of Fallen Cities (which they can use to detach the chains if the pact has been broken).

ALTERNATIVE – ASSAULT ON THE DOCK OF FALLEN CITIES: I’ve put the control room for the Dock of Fallen Cities on the flying fortress mostly to simplify my prep. In practice, there are some shortcomings: You can justify Zariel having the controls on her mothership, but logically it probably makes more sense for the Dock’s control center to be onsite. There’s also a real risk of déjà vu (with the PCs raiding the fortress for the contract, going to destroy the contract, and then having to raid the fortress again to disengage the chains). You can work around this by either allowing the PCs to set the controls to disengage once the contract is destroyed (so they can do both tasks in one raid) OR by making the second raid distinct and interesting in some way (by increasing security, for example).

Alternatively, you could move the control center to some spire or turret in the Dock of Fallen Cities and prep an alternative scenario in which the PCs (having somehow destroyed the contract) must now assault the Dock and release the chains!

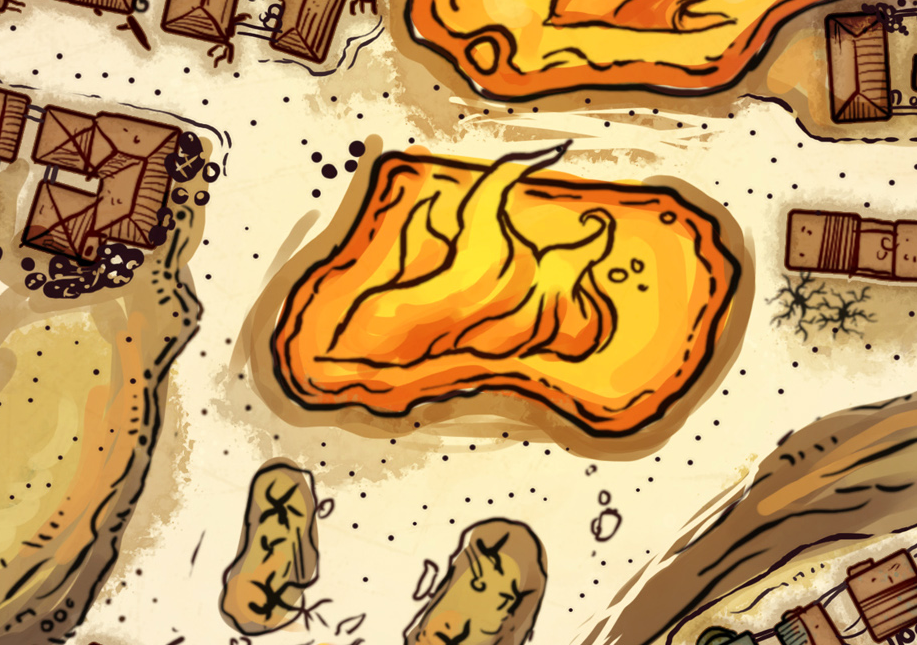

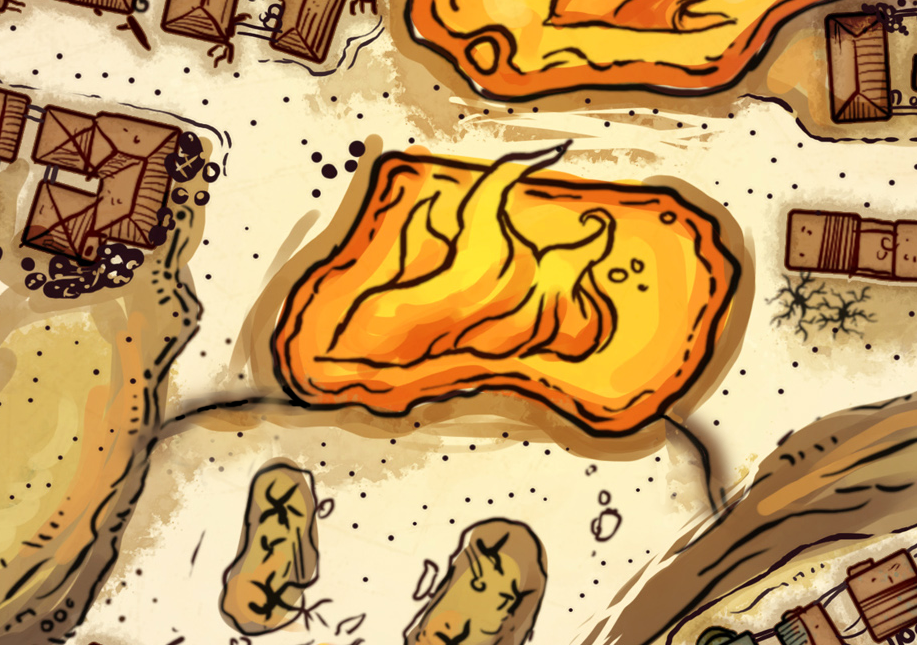

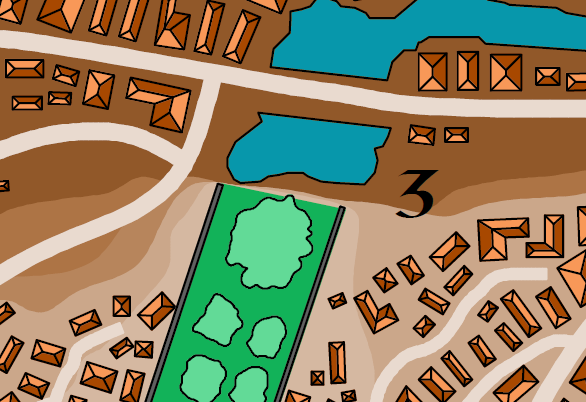

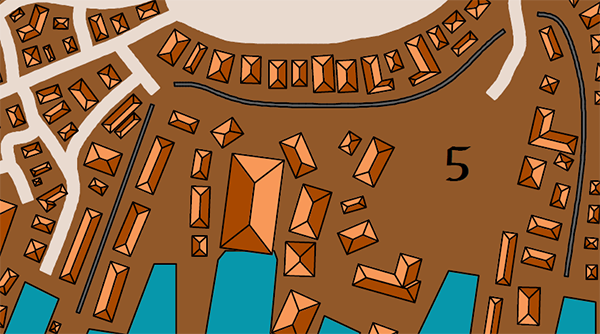

(For example, you could take this map, put this map at the bottom of it, and then put this map on top of the second map. Stock it up with a devilish security team and some magical defenses and away you go.)

POWERFUL ALLIES

There are some very powerful allies (or, at least, allies of convenience) that the PCs can make in Avernus. Likely candidates include Bel, Tiamat, and Gargauth (if he’s freed from the Shield of the Hidden Lord). Kostchtchie, Crokek’toeck, Yeenoghu, and maybe even Shummrath are significantly less likely options.

These allies can:

- Help the PCs kill Zariel. (Without such aid, it’s extremely unlikely the PCs can pull this off.)

- Sever the chains holding Elturel.

Almost without exception, all of them are more likely to do the latter than the former. And, of course, getting any of them to help is going to come at a price.

UNLOCKING THE COMPANION

Unlocking the Companion requires nine adamantine control rods which were lost when Zariel’s previous flying fortress crashed (DIA, p. 118). The unlocking process is briefly described on DIA, p. 154.

Note that I’m deliberately getting rid of the option of shattering the Companion by hitting it with the Sword of Zariel. Because the Sword can also sever the chains, my personal preference is for it not to be a one-stop shop for solving the whole problem. Your mileage may vary, however, and there’s nothing inherently wrong with a Sword-wielding PC swooping up and hacking the planetar out of its prison.

ALTERNATIVE – RODS, RODS, EVERYWHERE: As written, all nine adamantine control rods are located in the wrecked flying fortress. Alternatively, the fortress could have been looted decades ago and the rods scattered across the Avernian plains. Maybe Zariel has recovered some and they’re in her current fortress; maybe Bel has some; maybe some warlords prize them; maybe Maggie has one and doesn’t even know what it is (the PCs see it early in the campaign and later realize – OMG! – it was right in front of them the whole time!).

This will extend the campaign, but can be used to push the PCs into interacting more widely/deeply with locations in Avernus.

REVELATION LIST: THE BIG THREE

There are a number of revelations necessary for the PCs to complete the Avernian quest, so let’s whip up some revelation lists. Like the list in Part 3C: The Vanthampur Revelations, I’m including brief descriptions of each clue for clarity since many of these clues refer to material that won’t be available until after this post goes live.

HOW TO FREE ELTUREL: Break the pact and sever the chains to free the city. Then you’ll still need to find a way to take it home.

- Liashandra. The demon sent to stop Zariel from claiming Elturel will happily share her knowledge of how it can be prevented.

- Bel’s Forge. The original plans for the Dock of Fallen Cities would spell it out.

- Gargauth. If pushed to the brink (see Addendum: Playing Gargauth), Gargauth can explain how to save Elturel.

- Dock of Fallen Cities. (Partial) The control instrumentation would indicate that the chains cannot be disengaged unless the pact has been broken.

HOW TO BREAK THE PACT: Get the other half of the contract from Zariel, kill her, or make a bargain with her.

- Sylvira and Traxigor. They explain this in their “mission briefing” before the PCs go to Hellturel.

- Pherria Jynx & Ravengard. If the PCs tell them that they have Bellandi’s copy of the contract, Jynx knows enough lore to recognize what they have to do. Ravengard will explicitly tell them that this is what they should do.

- Gargauth.

- Talking to almost anyone in Hell. Pretty much everybody in Hell knows how to break an infernal contract.

HOW TO SEVER THE CHAINS: Can’t be done until the infernal contract is broken. Requires someone or something of incredible power. Zariel herself could do it using the control room on her flying fortress.

- Studying the Chains. DC 16 Intelligence (Arcana) check while studying the chains with proper tools/spells will make it clear how much strength would be required; and possibly that the chains have a remote connection to something that must be controlling them.

- Liashandra. She doesn’t know where the control room is, but knows that it must exist.

- Bel’s Forge. The original plans for the Dock of Fallen Cities. Bel himself may also offer it in trade.

- Gargauth. If pushed to the brink, Gargauth can tell them how “impossible” it is to release the chains.

HOW TO RETURN ELTUREL: Open the Companion and free the planetar.

- Bel’s Forge. The original plans for the Dock of Fallen Cities or Companion reveal the negative charge built up in the Companion.

- Dock of Fallen Cities Control Room. Instrumentation reveals the negative charge built up in the Companion.

- Gargauth. If pushed to the brink, Gargauth knows the planetar can save the city.

REVELATION LIST: ADDITIONAL REVELATIONS

The revelations above reveal WHAT the PCs need to do. These supporting revelations point to HOW they can do it.

ZARIEL WANTS THE SWORD: And therefore might be willing to trade something for it.

- The Vision from Torm (Lulu’s Memories)

- Maggie (Fort Knucklebones). She’s an expert in Zariel lore.

- Original Hellriders. Any of the original Hellriders know how important the Sword is to Zariel.

- Swordhunters. Found throughout the Avernian plains, seeking Zariel’s long-standing bounty for its recovery.

THE TRUE NATURE OF THE SOLAR INSIDIATOR: There’s a planetar locked inside (and maybe you should free it).

- Bel’s Forge. Where the Companion was built. The original plans can be found there; they have been notated to indicate that the control rods were lost in the wreck of Zariel’s previous flying fortress.

- Dock of Fallen Cities Control Room. Instrumentation reveals true nature of the Companion.

- Gargauth. Gargauth knows. He may be willing to reveal this information without being pushed to the brink if circumstances / the offer is right.

BEL’S FORGE IS WHERE THE COMPANION WAS BUILT: And you can find out how to open it there.

- Maggie (Fort Knucklebones). Knows the Companion was designed at Bel’s Forge.

- Gargauth. Doesn’t know how to open the Companion, but knows it was built at Bel’s Forge.

- Dock of Fallen Cities Control Room. Instrumentation bears Bel’s forgemark.

LOCATION OF THE CRASHED FLYING FORTRESS: Where the adamantine control rods are.

- Bel. He knows.

- Maggie. She knows.

- Avernian Warlord Rumors. PCs can hunt for rumors (see Part 7I).

THE SPARK IN THE SWORD: The Sword of Zariel contains a spark of Zariel’s divine light (and could be used to redeem her). This is not a proper revelation, but it is a significant info-dump so it may be worth pointing out here.

- Lulu’s Memories. Foreshadow the truth.

- Claiming the Sword. The moment of claiming the Sword makes it crystal clear that the spark exists (and why it exists). See Part 6D.