IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

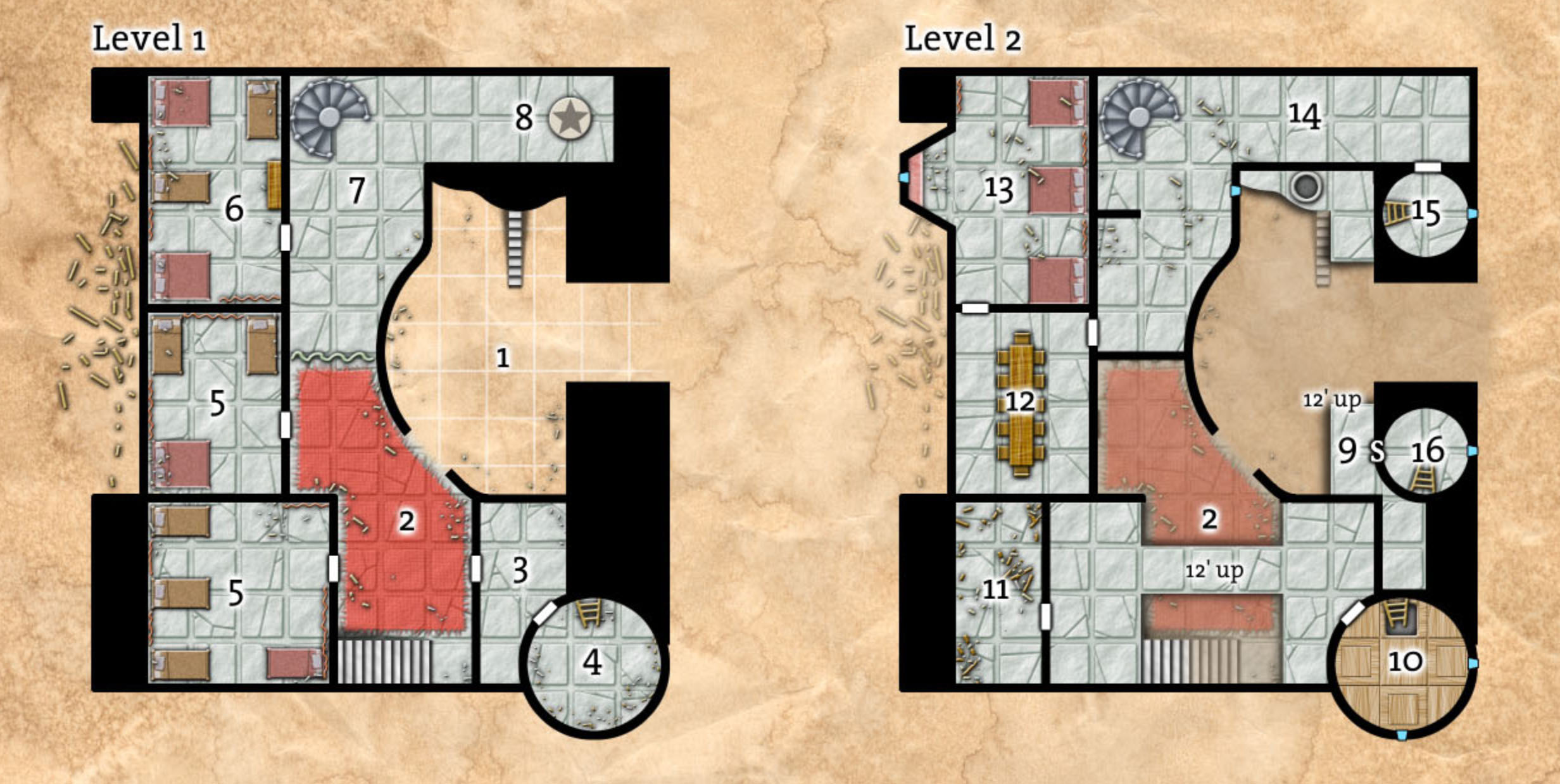

SESSION 23C: BENEATH PYTHONESS HOUSE

June 7th, 2008

The 10th Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

As far as they could tell, the keep was now empty except for themselves and the Cobbledman. They turned their attention to the statue in the first hall of the keep, and were surprised – as they rounded the corner towards it – to discover that a gap had opened in the statue’s stomach, revealing a circular depression into which the spiraled disc would fit perfectly.

They concluded that the depression must have opened when they had joined the two halves of the disc together.

Tee stepped forward, but Agnarr took the disc from her and fitted it carefully into the statue. With a twist of the wrist he was able to turn it counter-clockwise. With a rumbling groan and a burst of stale air, the statue rolled down the hall towards him. Agnarr stepped deftly to one side and saw, where the statue had been, a hole in the floor.

A twenty-foot shaft dropped straight down into a room with a ten-foot-high ceiling. Iron rungs set in the side of the shaft made it an easy climb. The chamber itself was of plain stone, but the floor to one side was interrupted by a fleshy membrane that quivered in the draft of air that flowed up towards the keep above. On the other side of the room, slumped against the wall, was a giant’s skeleton.

The skeleton was of titanic proportions and clad in age-tattered robes. The hem of these robes were embroidered with strange, round-shaped runes. Ranthir, glancing over from the iron rungs as he climbed down, instantly recognized them as Lithuin runes. These strange runes – now unreadable – were believed to have been used by the Titan Spawn of the legendary city of Lithuin. Only a few samples of such runes were known to survive. He was excited to study them in more detail.

But as Tee’s foot touched the floor, the skeleton began to stir – clouds of dust rising from its form as it slowly lurched to its feet. “Agnarr!” Tee cried. “Tor!”

Agnarr let go of the ladder and dropped to the floor (he was only a few feet above it in any case). Tor, taking up the rear guard as usual, had to jump clear of the wall to avoid hitting Ranthir and Dominic on the way down, but he landed easily, his sword already drawn.

Things went poorly at first: The titan spawn skeleton’s massive hand easily swept past their defenses, delivering bone-crushing blows. But then Dominic reached the floor and was able to lay his hands on Agnarr – at his touch, the familiar divine strength poured into Agnarr’s body and he grew to match the skeleton’s height and girth.

And despite his size, Agnarr was still possessed of greater speed and agility than the lumbering skeletal giant. Even as he finished his divinely-inspired growth, he whirled low and whipped his sword around – cutting at the giant’s shins and shearing straight through one of its legs.

“Don’t hurt the runes!” Ranthir cried, darting forward a few steps from where he stood in the corner (keeping a safe distance from the titanic struggle).

Dominic, summoning his inner strength, called upon the same divine energies a second time and let them flow into Tor.

Tor, growing as Agnarr had done, followed Agnarr’s example. Ducking low, his blow swept in from the opposite direction and cleaved the giant’s other leg. It crashed precipitously to the floor.

With perfect timing, Ranthir released an arcane attack – piercing the creature’s barrel-like eye socket with a blast of frigid energy that froze the bone. The jarring impact of its collapse caused the brittle bone to break and shatter, sending great gaping cracks racing across the dome of its skull.

Whatever enchantment had knit those bones together in undeath was broken, and the giant collapsed.

THE FRIGID CAVERN

Ranthir drew a knife and carefully cut away the Lithuin runes from the hem of the titan spawn’s robe. Meanwhile, the others were moving towards the fleshy membrane. It was slightly translucent and appeared to be stretched across another shaft leading down.

“What do we do?” Elestra asked.

“Well, the key we were looking for – are looking for – must be down here somewhere,” Tee said. “And there’s no where else to go.” She shrugged, drew her dragon pistol, and blasted the membrane.

The membrane ripped apart, and as it did so a howling blast of frigid air rushed up from the shaft below. Looking down through the hole, Tee could see that the frost-rimed shaft ended in another chamber twenty feet below, although all she could see of this chamber was a narrow patch of floor that appeared to be covered completely with ice.

“I’m going to go down and check it out.” Tee pulled out a sunrod, stepped off the edge of the shaft, and levitated down.

The chamber below appeared to be some sort of natural cave, but it was unnaturally – even impossibly – cold. The floor, walls, and ceiling of the cave were entirely coated in a thick layer of ice. The air was cold enough here that Tee thought there might be a real risk of frostbite.

Tee noticed that along one edge of this cavern, the ice appeared a little thinner. Looking at this broad patch more closely, she could see what appeared to be liquid water under the surface.

With a thoughtful look, she floated back up to the others. “Ranthir, I need you down there for a second.”

It took more than a second, but Ranthir was able to perform several divinations which confirmed that the unnatural cold was the result of a magical aura permeating these chambers. He could also tell that this magical aura extended through the liquid water in a tunnel that curved down and away before it passed behind too much solid rock for his arcane sight to penetrate. He attempted to unwork the magic of the aura, but failed.

Tee and Ranthir returned to the others and reported what they had found. “I think we have to go through that tunnel,” Tee said.

Tor shook his head. “If it’s as cold down there as it feels up here, we’ll all get hypothermia trying to swim through that water.”

“I know certain magicks that could protect us against the cold,” Elestra said.

“So do I,” Dominic said.

“Between the two of us, we should be able to protect everybody.”

“But we’ll need to prepare the proper spells,” Dominic said.

“I hate to wait,” Tee said. “I’ve got an appointment tomorrow. But if we need to rest, then we need to rest.”

“We could stay here,” Agnarr suggested.

Elestra gave the barbarian an incredulous look. “I think we should head back to the Ghostly Minstrel.”

“Assuming we can leave,” Tee said ominously.

“That’s true,” Tor said with a slightly worried tone.

Ranthir, meanwhile, had been getting a thoughtful look on his face. Now he suddenly turned to the others. “Come with me! Quickly!”

The others followed him as he climbed back up into the keep. Once everyone had joined him, he reached out and easily pulled the spiral contrivance out of the statue. As soon as he had done so, the statue rumbled back to its original position.

“It suddenly occurred to me that there was still a demon wandering around up here,” Ranthir said. “We could have been trapped.” He pushed the disc back into place. As the statue rumbled open again, he turned to Tee. “Once I’m down below, remove the disc and wait a couple of minutes. Then open it again.”

Tee followed his instructions. Ranthir, from below, watched the statue close above him… there was no keyhole for the spiraled disc down here. When Tee opened the statue again, Ranthir climbed up and informed the others. “As long as we’re down there, we can be trapped by anybody who comes along and removes the disc.”

HUNTING A DEMON

“We have to find that demon,” Tee said.

“And kill it,” Agnarr added.

“Well, we saw it descend beyond the outer walls, correct?” Ranthir said. “Perhaps we should start by searching the grounds outside.”

The others agreed, but after circling the keep they could see nowhere that the demon could have been hiding.

“Maybe he’s returned to his nest,” Ranthir suggested.

They walked back through the gate. “At least we know we can get out of here now,” Tee said.

“COME TO ME…” The familiar voice echoed through the keep.

“Didn’t he already say that?” Elestra asked.

“A couple of times, I think,” Tor said.

The demon had not, in fact, returned to its nest. Tee sighed heavily with frustration. “All right, let’s go back to the Minstrel. Maybe when we come back tomorrow, the demon will have returned and we’ll be able to kill it.”

But when they reached the gate, they found the invisible wall of force had once again been raised to block their passage.

“You’ve got to be joking,” Tee said, her hand pressed up against the energy field.

TRAPPED AGAIN

After a brief discussion, they decided that – if they were stuck here anyway – they might as well try a more mundane way of overcoming the frigid chamber below: Fire. They would gather up the older furniture from around the keep, drag it to the icy chamber, and then burn it.

But when they returned to the statue, they found that the hole in its stomach had closed up.

“It’s like its reset or something,” Elestra muttered.

“I MUST FEED…”

Now, standing in this hall, they were sure that the voice was emanating directly from the statue itself.

“It must be Segginal,” Ranthir concluded. “They bound Edlari so they could bind Segginal to this statue.”

“What does it mean by ‘feed’, do you think?” Elestra asked.

“I don’t know,” Tee said. “Maybe if we feed it, it’ll open the keyhole again.”

Tee walked up to the statue and touched it… she instantly felt a sharp pain and was overwhelmed by dizziness. Pulling her hand back, she saw that her fingertips were covered in a sheen of blood. She cursed.

Next, with a certain sense of desperation, Tee tried breaking the spiral key in half again (it broke naturally along the same line as before). Then she rejoined the two halves. There was another flash of light and the disc was made whole again… but the statue stubbornly remained shut.

“There might be another way,” Agnarr said. He led them back to the courtyard and pointed to the well. “It’s almost directly above the icy caverns below. There might be another way of reaching those caverns at the bottom of the well.” A way not blocked by the statue or its spirit.

Agnarr took the boots of levitation from Tee. He drew his sword – both for protection and for the light its flame would provide – and descended more than fifty feet into the dark, cramped well before he spotted the well water below him.

Something seemed to be stirring in that water… some great, white shape rising towards him. Instinctively Agnarr retreated back up the shaft, but before the slow power of the boots could take him far enough a flaccid arm of doughy white flesh burst out of the water and grasped his ankle.

Whatever the foul creature was, it began dragging its way up the length of Agnarr’s leg. A face of melted, white flesh emerged – gaping a maw of vicious, needle-like fangs.

But Agnarr had already reversed his grip on his sword and, as the creature lurched up towards him, the blade plunged down through its gullet and Agnarr, with a savage whipping of his thews, tore the creature in half.

Taking a deep breath of the now acrid air, Agnarr descended into the greasy, gore-spattered water… and met with a dead end. The water had a depth of perhaps fifteen feet, but did not open out into any larger cavern. He returned to the surface to report his disappointment to the others.

“What do we do?” Elestra asked again.

“Let’s try talking to the Cobbledman,” Tee suggested. “He lives here. He might know something about the statue.”

They found the Cobbledman in his tower.

“Cobbledman?” Tee asked tentatively, unsure of which head was in command.

“Tee!” The right head grinned broadly and the Cobbledman lurched to his feet. “You came back! … do you have food?”

Tee smiled. “Yes, I have food.”

She handed it over and the Cobbledman began munching contentedly.

“Do you know who Segginal is?” Tee asked.

The Cobbledman’s face became crestfallen. “Bad fat man!”

“He was a bad man?”

“Bad fat man!”

“Who is he?”

“Wuntad brought him. Now he watches. Watches all the time.”

“Does he do anything else?”

“Sometimes. Hurts when you touch him.”

“The statue?”

The Cobbledman nodded.

“Is there any way to stop him from watching?”

The Cobbledman shook his head. “But sometimes he goes away.”

“When does he go away?”

“Chaos is the key…”

Tee thanked him and gave him some more food. Then she climbed up to where the others were waiting. “The statue is Segginal. And he’s on a cycle.”

“Is there any way to speed it up?” Elestra asked.

Tee shook her head. “Not that he knew, anyway.”

Since it seemed as if they had nothing better to do for the moment, they began a complete search of Pythoness House again – from top to bottom. Perhaps the demon had snuck back into the keep and was hiding somewhere. Or perhaps there was some undiscovered nook or hidden door.

But that didn’t seem to be the case. Fortunately, as they finished their search and gathered back in the courtyard, the voice of the chaos spirit boomed forth once again: “CHAOS IS THE KEY…”

They returned to the statue and confirmed that, once again, the keyhole had opened on its stomach.

“The gate should be open now, too,” Tee said.

Since they understood the patterns and limitations of the ritual now, they felt comfortable in recuperating before journeying any deeper beneath the keep. They returned to the courtyard and headed towards the gate…

NEXT:

Running the Campaign: TBD – Campaign Journal: Session 23D

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index

Some of these clues will likely be quite straightforward: For example, the key in Room 11 that opens the door in Area 41.

Some of these clues will likely be quite straightforward: For example, the key in Room 11 that opens the door in Area 41.