Almost certainly the most famous sequence featuring traps is the beginning of Raiders of the Lost Ark. So, bearing in mind The Principle of Using Linear Mediums as RPG Examples, let’s take a look at what makes the sequence work.

TRAP 1 – COBWEBS. The first trap we see are the cobwebs filling the entrance. This an example of a naturally occurring trap (as opposed to one that was built). It’s also, perhaps surprisingly, a dynamic trap. Rather than simply dealing damage, it instead releases monsters for Indy to deal with. In this case, the monsters are spiders:

In D&D we might imagine swapping these out for giant spiders, but it’s really not necessary: What you have here are a bunch of spiders crawling over the PCs and they need to figure out how to get them off before getting bitten and poisoned.

TRAP 2 – SPIKE TRAP. Next up is a spike trap that shoots out from the wall to impale its unlucky victims. Somehow triggered by interrupting a beam of sunlight, this is clearly a magical trap and you’ll need to use your Intelligence (Arcana) skill to detect it.

Indy “disables” this trap by triggering it in a controlled way. (Player expertise trumps character expertise and bypasses the normal mechanic.)

The spikes contain the corpse of a former explorer, telling the story of what has happened in this dungeon before.

The spike trap also has an ongoing effect: We know it has a delayed reset because Satipo, Indy’s companion, triggers it while running back down the corridor later.

TRAP 3 – PIT TRAP. Next up we have a classic pit trap. This is actually an open pit, demonstrating that a trap doesn’t necessarily need to be hidden in order to pose a dilemma for the PCs to overcome. (This conceit is probably underused in D&D. It’s obviously not a one-true-way thing, but it can also be a self-diagnostic tool: If it would be pointless for a trap to exist if the PCs automatically spotted it, that may be a good indicator that the trap isn’t interesting enough.)

Instead of somehow disabling the pit, of course, Indy solves the problem by using his whip to swing across it. He easily makes his Dexterity (Acrobatics) check, but Satipo flubs his. Rather than immediately dropping him in the pit, however, the hypothetical GM uses fortune-in-the-middle to leave him dangling helplessly. Indy has to leap in with a Strength (Athletics) check to haul him in.

TRAP 4 – DART TRAP. Next we have the (probably poison) dart trap. Indiana Jones succeeds on his Intelligence (Investigation) check to find the trigger. Once he’s identified one trigger (camouflaged with a covering of dirt), he can easily recognize the other triggers in the room. This is somewhat compressed, but still demonstrates a local theme.

Jones once again decides not to disable the trap and instead makes a Dexterity (Acrobatics) check to make his way across the room.

TRAP 5 – THE IDOL’S PEDESTAL. Everyone knows this one, right? Even if you haven’t actually seen the movie, I feel like you already know this one: Indiana Jones tries to replace the idol with a sand-filled bag of equal weight to avoid triggering the trap.

(And if you haven’t seen Raiders of the Lost Ark, I really can’t emphasize enough how you should immediately stop reading this article and go do that. Not because of spoilers – we’re just discussing the first scene here – but because you’re missing out on something awesome.)

Something to note here is that Indiana Jones very specifically filled the bag with sand outside the temple. He knew this trap would be here. Remember when I said that you’ll know you’ve gotten the balance right when the PCs start actively trying to collect intel on the traps they might encounter? And the pay-off will be memorable problem-solving (that, in this case, will resonate through a bajillion homages)?

Yeah. Like that.

The idol’s pedestal also features a delayed onset. This is another technique you can use for fortune-in-the-middle resolutions.

This is also the first trap-related skill check Indiana Jones has failed. Notice that the failure doesn’t zap him for damage!

Instead, we then have one of the greatest dynamic traps of all time as the entire temple begins to collapse! A whole new problem that prompts both Satipo and Indy to flee back out of the temple, retracing their steps through the same traps they came through to get here.

This is where the specificity with which the previous traps were detected and dealt with pays off a second time. This is why you want to avoid the simplicity of “a successful Disable check = the trap no longer exists.” For example, if Jones had taken the time to disable the dart triggers as he entered the temple, he’d now have a clear path to exit. But he didn’t, and now he doesn’t have time to carefully pick his way through the traps.

His only option is to try to run out of the room so quickly that the darts can’t hit him. We might model this as a Jones taking a Dodge action (so that the darts make attack rolls at disadvantage). Or maybe it makes more sense for Jones to make a Dexterity (Acrobatics) check at disadvantage to see if he can move fast enough.

(Notice how the same trap can be dealt with in different ways – both in the fiction and in the mechanics – because, once again, the nature of the trap is specific.)

We return to the pit. Because Jones specifically left his whip in situ, Satipo can use it to swing across. This time he makes his Dexterity (Acrobatics) check, but pulls the whip after him.

Now things get interesting, as Satipo demands that Indy throw him the idol before he’ll throw him the whip. This is an example of how traps can be incorporated into non-combat scenes: This is a social dilemma and negotiation which is entirely predicated on the presence of the trap!

(We might ask ourselves how often this sort of thing really happens. But in pulp fiction? It happens all the time. When in doubt, dangle a loved one over a cauldron of boiling oil. Or negotiate a terrible price for the antidote to a poison dart.)

Satipo reneges on the deal, drops the whip, and leaves. “Adios, señor.”

Indy takes a running start and makes a Strength (Athletics) check to just leap across it.

(What’s that? 5th Edition uses flat jump distances instead of making you roll a check for it? Well, that would certainly make this moment incredibly boring. But it’s not like D&D is based on pulp adventure stories, so I’m sure perilous leaps won’t come up that often and it therefore makes perfect sense for that to be the rule… Anyway, I digress.)

Indy fails his check, but the GM once again uses a fortune-in-the-middle technique (possibly prompted by a partial failure) and has him land on the far edge of the pit. He’s going to have to try to climb up by grabbing a vine.

Another partial failure on the Strength (Athletics) check! He manages to grab the vine, but it’s not secure and he nearly slides back into the pit before catching himself!

Here we see multiple traps being brought together for a combinatory effect: Not only is Jones trying to get past the pit trap, but there’s a wall descending that will cut him off from the exit. He’s only got 3 rounds before his exit is cut off, and he’s burning through them with these failed checks!

Indy, of course, finally makes his Strength (Athletics) check and scrambles under the door, managing to grab his whip at the last minute. Running down the corridor he discovers that Satipo has, as we mentioned before, (a) made the strategic decision not to search for traps because the temple was collapsing around him and (b) failed to remember (via player expertise) that the spike trap was there.

(Once again, if they had disabled this trap instead of simply bypassing it on their way in, this would have played out very differently.)

This, of course, brings us to the other great iconic trap from this sequence:

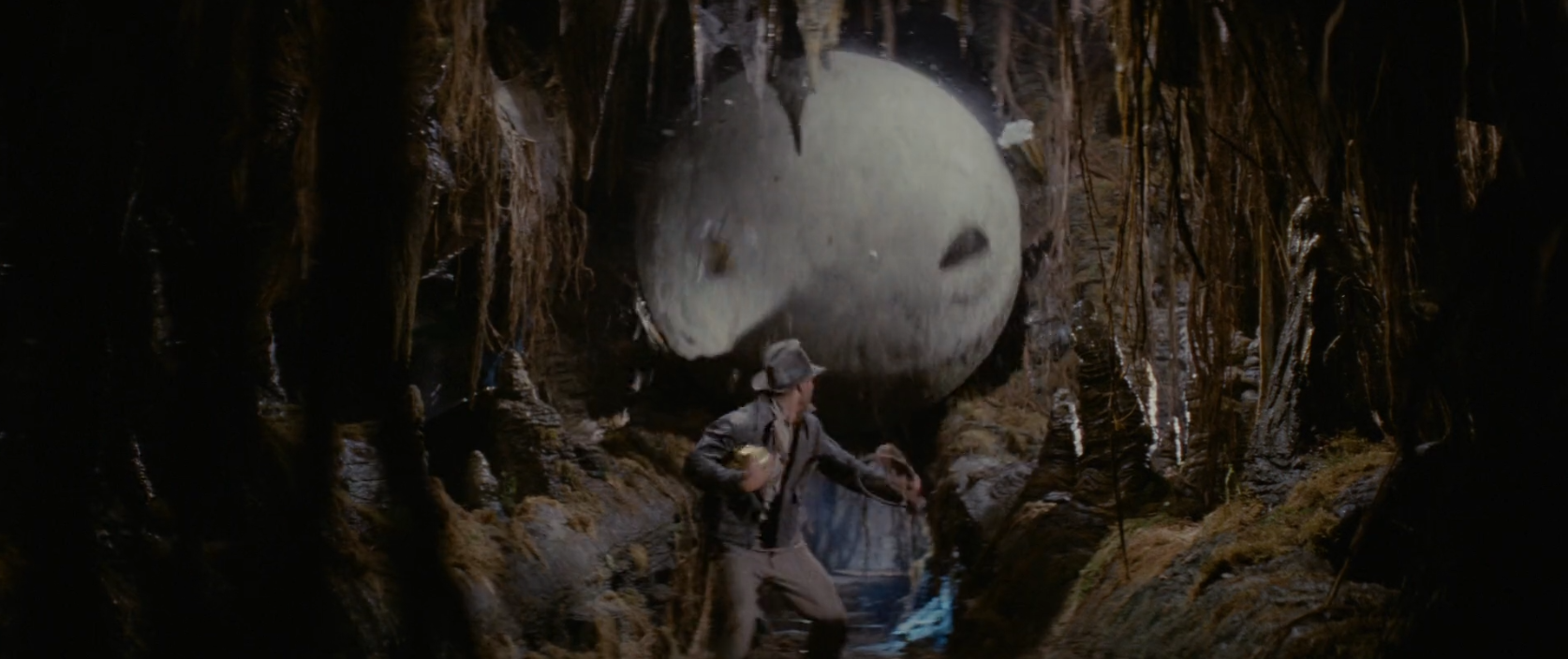

TRAP 6 – BIG-ASS BOULDER. This may or may not be a new trap, actually. It’s quite likely that the boulder is triggered by the idol’s pedestal, being an example of a trap having a non-local effect in the dungeon and just one more step in the trap’s wide-ranging “seal the temple” schtick.

Alternatively, it’s possible that Indy did something to trigger the boulder as he was exiting. If so, this trigger probably only becomes active as a result of the trap on the idol’s pedestal being triggered. (We didn’t specifically discuss triggers that are only conditionally active, but it’s a subset of trigger uncertainty.)

Indy then leaps through the spider webs (which have apparently not reset with more spiders) and hurtles out of the temple.

End of sequence.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Is this an example of a good D&D dungeon?

Probably not. It’s too linear even for a short dungeon, in my opinion. (Although if you do have a relatively linear sequence with a lot of traps that you’re going to force the players through, the fact that so many of the traps are immediately obvious or already known to Jones before he enters the dungeon – the webs, the pit, the idol’s pedestal – may be a good tip: Put the interest on what the PCs do about the traps instead of whether or not they find the traps; and if there’s no interest to be found there, then you probably need to fix that.)

But the point of the exercise, of course, is not the totality of dungeon design. It’s about how we can bring cool traps to our tables. In this, I think, Indy has successfully given us some insight.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that hypothetical GM Steven Spielberg included an actual D&D game in ET a year later.

I suspect (thought I can’t actually back this up) that most GMs either ignore the fixed-jump rules altogether *or* treat the fixed jump length as a minimum and require a check for anything beyond it. The latter is what I would do if I were running a game. (In fact, the rules explicitly suggest this for high jumps, so it isn’t much of a stretch to apply it to long jumps as well.)

“This is also the first trap-related skill check Indiana Jones has failed.”

What about the webs? Would you allow a check to bypass the webs without disturbing the spiders (and if so, what check)? Would you require a check to brush the spiders off without getting bit?

Love Raiders of the Lost Ark, perhaps the best adventure movie filmed 😀

It’s interesting also that the Indy temple traps inverts the standard “find then inactivate/bypass the trap” process flow when the idol re-activates them at the end, which changes the nature of the threat of the traps. They’re now double-threats: 1) yes, they’re dangerous for their potential to damage the PCs, but now their primary threat is revealed as 2) the time required to safely navigate/byapss each trap while the the temple is collapsing around them and/or the boulder is sealing off the front door.

Allan.

Another useful function of the first trap is that it immediately communicates what the dungeon is about.

The trap tells the players that the dungeon is about complex and interactive traps, without punishing them for failing to roll perception on every inch of the dungeon. Instead disturbing the webs presents them with a second chance to avoid or mitigate the trap’s damage.

Great minds think alike, buddy:

https://terriblesorcery.blogspot.com/2018/08/the-best-d-film-ever-made.html