The Yawning Portal seems utterly synonymous with the Forgotten Realms today, but it actually didn’t appear in the original Forgotten Realm Campaign Setting boxed set, published in July 1987.

The wait was not particularly long, however. By the end of the year, driven in part by the prodigious amount of Realmslore Ed Greenwood had created for his setting, TSR had released nearly a dozen Forgotten Realms books, including FR1 Waterdeep and the North and the first details of Durnan’s tavern.

(The “and the North” portion of the title was actually something of a misnomer. According to Shannon Appelcline, Greenwood had warned TSR that his Waterdeep lore alone was enough to fill a book. And that was more than true: Almost all of the material about the rest of the North got knocked out of FR1 and later handed over to Jennell Jaquays for FR5 The Savage Frontier. It’s unclear why they didn’t just drop “and the North” from the title. Perhaps they felt locked in by the title they had solicited? But I digress.)

THE EARLY DAYS

In FR1 Waterdeep and the North, the Yawning Portal appears as Building #4:

4. The Yawning Portal (inn) – See Durnan, p. 17

Thus, most of the original information about the Yawning Portal is actually contained in the NPC write-up of its proprietor, and these are fairly barebones: It contains a “well-like shaft leading down into Undermountain, the subterranean ways under Mount Waterdeep.”

The Yawning Portal’s next appearance is in the City System (1988), a boxed set filled to the brim with twelve  huge poster maps, ten of which joined together to form an insanely huge map of the city. The City System was designed to be used in conjunction with FR1 Waterdeep and the North: FR1 described the city. The boxed set only included the huge maps and a small pamphlet with useful tools (like random Street Scenes and indices).

huge poster maps, ten of which joined together to form an insanely huge map of the city. The City System was designed to be used in conjunction with FR1 Waterdeep and the North: FR1 described the city. The boxed set only included the huge maps and a small pamphlet with useful tools (like random Street Scenes and indices).

(This confused the heck out of me as a kid, who bought City System but never saw a copy of FR1 at the local game store.)

In the City System, therefore, the Yawning Portal remains Building #4, but no additional text description is provided. The boxed set does include the first official map of the interior of the inn, but we’ll come back to this later.

The Yawning Portal’s next appearance was in the adventure module FRE3 Waterdeep (1989), also by Ed Greenwood. The PCs are taken to the Yawning Portal by Elminster and Khelben Arunsun the Blackstaff. The adventure tells DMs that they can use the map from the City System boxed set, but also includes a much more detailed description of the Portal’s interior:

- It’s a “large, rambling building.”

- A signboard above the “round door” reads “The Yawning Portal,” and “on the door itself, someone has chalked ‘Come Ye Inn.’” (sic)

- It is dimly lit.

- There’s at least one private side room.

- A 14-year-old girl works as a server.

Most notably, FRE3 adds a second well to the Yawning Portal:

Durnan leads the party to the back of the inn. (…) The innkeeper lifts a huge bar from the door with one hand, as though it weighs nothing, and leans it against the wall. Then he opens the door and leads you into a dark room. The torch’s flickering light shows a covered wall and a table. On the table lie coils of rope, a tinder box, and a half dozen unlit torches…

“I haven’t been down this back way in some time,” he says. “We usually go down the dry one; it keeps the water cleaner.”

At some distance down the well, there’s a side tunnel that leads into a cavernous region of Undermountain which includes the Pool of Loss.

(The reason for this addition is fairly obvious: The adventure wants to send the PCs to Undermountain, but doesn’t have the space or page count to do that. So Durnan has a short cut that takes the PCs more or less directly to where they need to go.)

Despite only being an adventure module, FRE3 Waterdeep was frequently cited in TSR products as the authoritative source for the Yawning Portal. This notably includes the Ruins of Undermountain boxed set (1991), which rather hilariously notes:

More about Durnan and the inn can be found in the sourcebook FR1/Waterdeep And The North, the City System boxed set, and the module FRE3/Waterdeep. Details of the inn itself have been omitted from these pages to allow DMs free rein in customizing this rambling, shady place.

“We’ve detailed this location in THREE different books, but we haven’t included those details here so that you can have ‘free rein’ in customizing it.” Yeah. Sure. Whatever you say, TSR.

(Ruins of Undermountain II actually doubles down on the absurdity here, similarly demurring to describe the inn, but this time asserting that “the Yawning Portal is detailed in the original Ruins of Undermountain boxed set,” where, of course, readers will instead find the boxed set declaring that it definitely does no such thing.)

But because the Portal actually hasn’t been particularly detailed previously, Ruins of Undermountain does add several new details:

- “The Portal is a rambling, dingy, blue-tapestried building of smoothly carved pillars and paneling.”

- It is located “squarely on the site of the long-vanished tower and fortified warehouses of the archmage Halaster Blackcloak.”

It is the “the only known entrance” to Undermountain accessible to the general public.

It is the “the only known entrance” to Undermountain accessible to the general public.- The first well is 40’ in diameter and located in the main taproom. It’s “situated between the bar and most of the dining tables” and surrounded by a “waist-high, foot-thick stone ring/rampart.” Lit torches are placed around the circumference of the well and there’s a massive block-and-tackle “hanging from a stone lintel above the well, hiding among the roof beams.” The well is 140 feet deep, dark below 50 feet, and there are noisemakers at the bottom (used to signal the taproom for the rope to be lowered).

- You pay Durnan 1 gold piece per head to be lowered into Undermountain.

- The “wet well,” which is used only for washing water, is lesser-known and hidden in a backroom. It leads to a section of the dungeon not detailed in the boxed set, but which connects “with the city sewers in many places” and the plane of Hades (via the Pool of Loss). It’s possible that there are actually multiple passages intersecting the wet well, but the phrasing here is ambiguous.

Now, you might expect to find some reference to the Yawning Portal in Volo’s Guide to Waterdeep (1992), but not really. It has a city map which my copy lacks, but which I believe is essentially identical to the one from FR1 Waterdeep and the North and on which the Portal remains Building #4. And it has a footnote telling you to go check out FRE3 Waterdeep.

So our next stop is actually the City of Splendors boxed set (1994), which is very much designed to replace both FR1 Waterdeep and the North and the City System boxed set (although it lacks the latter’s prodigious map). The numbered key for Waterdeep is overhauled with ward-based numbering, and the Yawning Portal is now C48 (C for the Castle Ward).

City of Splendors mostly compiles the known information about the Yawning Portal from all of our previous sources, but there are a few notable new details:

- Durnan established the Yawning Portal in 1306 DR.

- The Yawning Portal is a 3-story Class C building. (Class C buildings are generally the “tall row houses that line the streets” with shops on the ground floor and offices or apartments above that, but the “better-kept” inns and taverns are also grouped in here.)

- It now also costs 1 gold piece to get pulled OUT of Undermountain. (Make sure to budget accordingly.) I believe this is also the first reference to patrons wagering on would-be adventurers.

There is actually now a long break in the Yawning Portal being described in RPG supplements, with one interesting sidenote in Skullport (1999), which claims in two different places (p. 9 and 64) that there is a secret door in the Yawning Portal’s wine cellar which leads, along a side passage, to the Bonewatch Pass, a tunnel which runs all the way to Skullport.

THE VIDEO GAME ERA

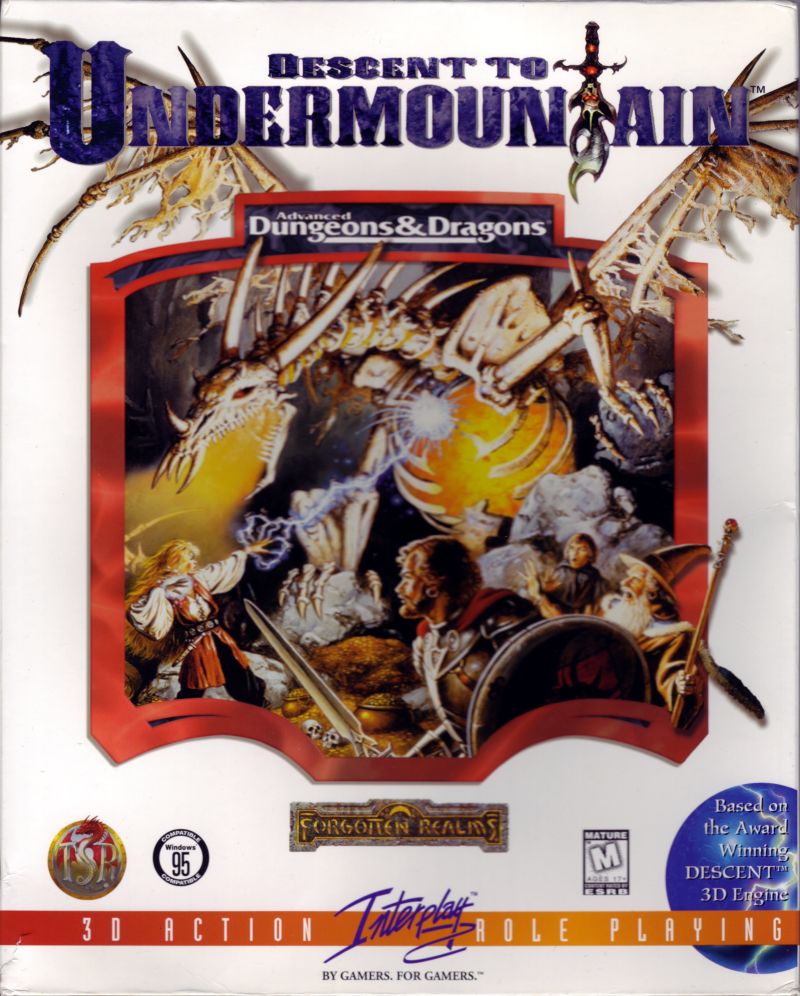

During this gap in RPG books from 1994-2004, the Yawning Portal actually makes two notable appearances in video games: Descent to Undermountain in 1994 and Neverwinter Nights: Hordes of the Underdark in 2003.

These are particularly notable because, as far as I can tell, they’re the first visual depictions of the tavern.

Note: Some online sources claim that the Yawning Portal also appeared in the Eye of the Beholder games, but although there is an unnamed tavern that briefly appears in the later games of that trilogy, there’s nothing to suggest that it’s the Yawning Portal.

The depiction of the tavern in Descent to Undermountain is rather severely limited by the FPS technology of  time, with everything rendered in Doom-style blocks.

time, with everything rendered in Doom-style blocks.

- The common room is depicted as a big square room, with a big square well.

- Rather than a rope dangling over the well, there’s a wooden platform with a skull-embossed cage that’s lowered into Undermountain.

- The common room is surrounded by a hallway studded with guest rooms. (The guests are delightfully eclectic, including a mind flayer, a drow, and the Open Lord’s son.)

Neverwinter Nights: Hordes of the Underdark has a very different design for the inn. The game starts on the second floor, which features:

- An armory in the back corner of the inn, stocked with adventuring gear.

- A large common room, which is sort of a hostel with multiple bunkbeds and a small library of books.

A stair leads down to the first floor where there’s:

- Another common room, this one with cheap cots for sleeping but also accoutered with medical supplies for treating those injured escaping from Undermountain

- The taproom which… uh… lacks any taps? (The games’ presentation is a little ramshackle here.)

Notably the taproom also lacks a well. The well is instead located in the basement, and is less of a well and more of a “gaping chasm.” A “well” is located on a rocky spur jutting out over the chasm, and is protected by a clockwork brass dome that irises up and down.

(The pointlessness of this defensive device is established a moment later when a beholder floats up out of the chasm and near-murders Durnan.)

More recently, in the new Neverwinter game (2019), the Yawning Portal is depicted once more:

This presentation is heavily influenced by the Portal’s presentation in Waterdeep: Dragon Heist (as we’ll see below).

- The taproom is shown to have a vaulted ceiling all the way to the third floor, with balconies featuring additional seating lining three sides of the room (and skylights!).

- The three-sided bar juts out into the room.