Take a moment to consider this:

Take a moment to consider this:

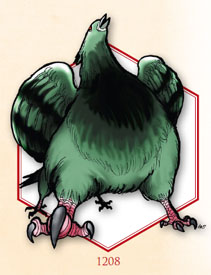

A four-legged pigeon is the size of an apatosaurus, and in combat a display of feathers rises behind the creature’s head. (…) At will, the giant pigeon can shape-shift into a giant yellow spider.

If that sort of thing — along with 7′ tall parrots who are always on fire and 12′ long blue jays without legs — sounds interesting and useful to you, then you’re going to love Isle of the Unknown. If it doesn’t, however, then you’re probably going to be struggling to find much utility between its covers.

Isle of the Unknown presents an interesting contrast to Carcosa (Geoffrey McKinney’s other deluxe hexcrawl product from Lamentations of the Flame Princess). Unlike the bland and boring key entries for Carcosa, Isle of the Unknown — which describes an island roughly 150 miles wide — is generally specific, clever, and creative. Unfortunately, it presents a very different set of problems which, nevertheless, cripple the product for me.

First, there are the monsters. Although occasionally spiced with some interesting abilities, they really are giant pigeons all the way down: Pick a random animal. Make it bigger than normal. Randomly determine the number of limbs it possesses. Now, randomly combine it with another animal; light it on fire; have it ooze pus; or give it a random spell-like ability. Ta-Da! You’ve re-created the vast majority of the monsters in this book.

Second, although in a hex-to-hex comparison Isle of the Unknown is much improved compared to Carcosa, in totality it ends up being just as bland by over-saturating its themes.

Second, although in a hex-to-hex comparison Isle of the Unknown is much improved compared to Carcosa, in totality it ends up being just as bland by over-saturating its themes.

Let me explain: I think themes are very important in creating interesting hexcrawl or dungeoncrawl keys. Themes give a location its identity and make it memorable. Without a proper theme, a ‘crawl turns into a random funhouse. But if a theme is too narrow and relied on too heavily, then it becomes repetitive. (For example, enchanted vales which remain perpetually in springtime regardless of the weather outside simply stop being magical when there are something like a dozen of them scattered around the island.)

In the case of Isle of the Unknown, McKinney describes the scope of his key like this:

To aid the Referee, only the weird, fantastical, and magical is described herein. The mundane is left to the discretion of the campaign Referee, to be supplied according to the characteristics of his own conceptions or campaign world. Detailed encounter tables (for example) of French knights, monks, pilgrims, etc. would be of scant use to a Referee whose campaign world is a fantasy version of pre-Colombian America. Similar considerations led to the exclusion of most proper names.

Couple important things to understand about this: First, it’s untrue. The key includes a lot of “mundane” detail (most notably all the major communities on the island). Second, it’s nonsense. You can’t say “if I don’t give this guy a proper name, then it’ll be easy to slot him in as a pre-Colombian American” and then describe him as “a robust and jovial man of middle years with blue eyes and curling reddish hair and beard (…) he loves nothing so much as the hunt, save perhaps his dozen Scottish Deerhounds”.

What McKinney really means is that 95% of his hex key is going to be broken down into three categories: Monsters, Magical Statues, and high-level Magic-Users/Clerics who all live by themselves as bucolic hermits.

And on an individual level, most of this content is at least interesting. But if you attempted to actually run a hexcrawl using this hex key, the result would be incredibly boring due to its repetition: “Magic statue, bucolic hermit, bucolic hermit, giant parrot, magic statue, humanoid bluejay, magic statue, magic statue…”

So, ultimately, I’m forced to conclude that the book is not very useful in its intended function as a hexcrawl. However, it may have some value as an inefficiently organized bestiary and the like… but only if you like giant, flaming parrots.

In closing, it must be noted that, once again, Lamentations of the Flame Princess have created a book which is both beautiful and useful. Although completely different in its aesthetic from Carcosa, Isle of the Unknown is nevertheless gorgeous: Excellent illustrations, rich lay-out, high-quality paper, durable binding. (My only caveat would be that the map of the island, while very pretty, does not clearly identify the terrain type in each hex. From a utility standpoint, that’s a fatal flaw in a hexcrawl product.)

Style: 5

Substance: 3