Tagline: Cheapass Games are cool. Bad Bond jokes are cool. This game is cool. You cool with that? Or do I have to kill you in a bizarre, drawn out fashion which will leave plenty of opportunities to escape?

“Imagine, just once, luring the master spy into your evil lair and putting a bullet in his head. Imagine resisting the temptation to gloat over your prize, to tell him your secret plans, to let him escape certain death and blow up your lair in the process. Imagine winning.

“Imagine, just once, luring the master spy into your evil lair and putting a bullet in his head. Imagine resisting the temptation to gloat over your prize, to tell him your secret plans, to let him escape certain death and blow up your lair in the process. Imagine winning.

Yeah, right.

Before I kill you, Mister Bond, I am going to tell you my entire life story, because I believe that you are the only man alive who would understand…”

I’ve been hearing good things about Cheapass Games for quite awhile now, but only last month did I finally find a store which sells them. Whoa boy, has it been worth the wait. Before I Kill You, Mister Bond… is one of the coolest games I’ve ever played, simply because its conceptual basis is so excellent for a game among friends.

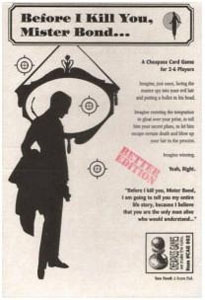

For those who haven’t been let in on the secret yet, Cheapass Games produces games with ultra-original concepts and mechanics on very cheap materials so that they can keep the prices down. Do not confuse “cheap” with poor in quality, though. Before I Kill You, Mister Bond… comes in a handsomely designed white paper envelope which has been printed with a simple, but elegant cover. The instructions take up both sides of a single sheet of paper and there are two decks of cards – one printed on yellowish card stock, the other on greenish card stock. Everything is professionally put together and printed – it just doesn’t come in a cardboard box with laminated cards. Games, as their mission statement says, are fun because of how they’re designed – not because of the clever pieces of plastic with which they come. The pay-off to you is that Cheapass Games are just that – cheap as hell. If Before I Kill You, Mister Bond… was produced like most other games it would cost $20, not $5.

The concept of the game is simple: You take on the role of a super-villain in the classic James Bond tradition – massive secret bases, advanced technological wonders, and master plans… all ruined by our need to design Rube Goldberg machines to kill off the super-spy who comes after us. (Anyone who has seen Austin Powers knows the joke.)

The deck is made of three types of cards — lairs, spies, and doublers. The spies are a different color in order to make them easy to find… “just like in real life. ‘Hi! I’m Doctor Kelley! Any messages for me? Say, I’m a Spy!’” Each player is dealt a hand of cards and play begins in a clockwise manner.

Each turn consists of two phases. In the first phase you can play a single lair card from your own hand. Lair cards have different point values and the value of your lair is the point total of all the lair cards you have played. In the second phase you can play a spy card – either from your hand, anyone else’s hand, or from the top of the deck. You can also play a team of spies from your own hand (but not anyone else’s or the top of the deck). You play the spy cards against a particular lair – either your own, or someone else’s. Each spy has a point value (a team of spies has a point value equal to their total). If that value is larger than the lair then the spy infiltrates the lair and destroys it. If that value is smaller or equal to the value of the lair then the spy is captured.

Once a spy is captured the owner of the lair can either kill the spy or taunt the spy. If they kill the spy they score the number of points the spy is worth. The other option is to play a doubler card, which will double the value of the spy. Each doubler card is printed with a letter and has a matching doubler card with an identical letter somewhere else in the deck. If a doubler card is played it can be challenged by its matched pair. If this challenge takes place the spy escapes and the lair is destroyed.

So, overall, your goal is to build a lair with which to catch spies and score points. The first person to score 30 points wins the game.

The place where the game really shines, though, is the comedic interaction of the players. The cards are all jokes playing off the spy adventure/thriller genre (the Bond films, The Avengers, etc.). Most notable are the doubler cards – all of which are printed with cheezy super-villain taunts, such as: “I shall taunt you with this deadly weapon, blithely unaware that a child could have untied those ropes by now.” Having the players read these aloud in their best super-villain accents is truly the coolest part of the game.

There is, unfortunately, a massive problem with this game: It doesn’t work. I playtested it using a group of three and then a group of four players (it’s advertised as being for 2-6) and the dynamics and balance of the deck simply don’t work properly to let the rules fully realize themselves. Because spies can be played from essentially anywhere it is impossible to build up teams of spies, because any attempt to do so will invariably have someone else use your spies against you or for themselves. Lairs are difficult to get established (because they are easy to destroy), but once they are established they are almost impossible to destroy because you can’t build up teams of spies. Because there are an equal number of lairs, spies, and doublers in the deck, invariably by the time any sort of serious spy-catching is going on (because the lairs take so long to build up to a point where they can capture spies) everyone has built up a huge reserve of doubler cards – making it infeasible to play any of them (because someone else invariably has the matching card).

In the end these flaws meant that all the games we played (and we played nearly a dozen) went down the exact same route: Most lairs were wiped out repeatedly until one person got a lair large enough so that it couldn’t destroyed. That person then won the game. Very few doublers were ever played, because whenever they were it only resulted in the person’s lair being wiped out.

The rules themselves, IMO, work, but the deck of cards simply isn’t properly balanced. Plus more cards overall would have been nice because the phrases on these got tired pretty quick – and its the panache and cleverness of those phrases which are the primary strength of this game.

Nonetheless, this is a pretty classy game. At $5 it ain’t a bad buy, particularly since you can get quite a few laughs out of it.

Style: 5

Substance: 3

Writers: James Ernest

Publisher: Cheapass Games

Price: $4.95

Page Count: n/a

ISBN: n/a

Originally Posted: 1999/04/13

This is a game I enjoyed playing for about 3 weeks. Then I wrote a review about how much I liked it. Then I never played it again. Games that are fun only because the content on the cards is amusing simply don’t last. (See, also, Munchkin Quest.)

Also: 14 years later, the idea of needing to wait for a game until “finally finding a store that sells them” is simply adorable.

If you’re interested in checking this game out, you should be aware that Cheapass Games got hit with a cease-and-desist order in 2000. The game is now marketed as James Ernest’s Totally Renamed Spy Game.

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.