I’m fairly blessed with good fortune when it comes to having people to play games with. My work in theater serves to introduce me to a constant procession of intelligent, creative, wonderful people. (This carries with it the associated curse that it can often be hard to actually find time to hang out with all these intelligent, creative, and wonderful people when you’re all on mutually incompatible show schedules. But as curses go, that one’s not so bad in the grand scheme of things.

I’m fairly blessed with good fortune when it comes to having people to play games with. My work in theater serves to introduce me to a constant procession of intelligent, creative, wonderful people. (This carries with it the associated curse that it can often be hard to actually find time to hang out with all these intelligent, creative, and wonderful people when you’re all on mutually incompatible show schedules. But as curses go, that one’s not so bad in the grand scheme of things.

Intelligent, creative, and wonderful people make for excellent gaming compatriots. And, as a result, I frequently find myself in the position of needing to introduce new people to the sort of games that aren’t Monopoly, Trivial Pursuit, or Pictionary. (Although I’ll often discover that a lot of these people were already dedicated gamers or used to be gamers and would love to be again; I just had no idea until I broached the subject. How many people do you know that you could be gaming with if you just talked to them about it?) Over years of experimentation, I have found that there are effective ways of doing this and less-than-effective ways of doing this.

PICKING A GAME

What I’m specifically going to be talking about today is introducing people to nontraditional, theme-rich boardgames. (Introducing new players to roleplaying games is a different, albeit similar process.) So which game should you use? In my opinion, there are three key factors to consider:

(1) Find a game with a theme that appeals to the new player.

This is pretty basic and should be fairly self-evident. If they like science fiction, introduce them a science fiction game. If they like Victorian London, introduce them to a Jack the Ripper game. And so forth.

(2) Know the game well and practice your introductory spiel.

Don’t try to learn a new game at the same time you’re teaching it to a new player. Study the game and know it well. You need to be completely comfortable with it so that you can quickly answer any questions they might have about game play without delaying to look it up in the rulebook. Your introductory spiel for the game, on the other hand, is the real lynchpin for successfully introducing people to the game. We’ll be delving into that in just a minute.

(3) Co-op games are generally a better way of introducing people to non-traditional gaming.

The advantage of a co-op game is that it’s not necessary for a new player to understand every tactical nuance of the rules: You can introduce the more nitpicky depths of the rules during play without prejudice. (In a competitive game, by contrast, a player needs to basically understand all the rules in all their variations because otherwise they can’t actually compete: It’s not fair for you to suddenly reveal that Queens can move in any direction half-way through a game of Chess. A lot of non-traditional competitive games also feature hidden components, which can make it more difficult or impossible for you to coach new players mid-game.)

All of this is only true, however, if you make sure the new players are included in the decision-making process of the co-op game. If you’ve got a table that defaults towards alpha-quarterbacking (in which the most experienced player makes all the decisions), then virtually all co-op games suck in general and completely suck for new players.

THE INTRODUCTORY SPIEL

For most of the co-op game sin my collection — Arkham Horror, Betrayal at House on the Hill, Knizia’s Lord of the Rings, Level 7: Escape, etc. — I’ve therefore perfected a presentation of the basic rules for the game which generally takes no more than 5 minutes. As an example of this, let’s consider Arkham Horror. (And I’m picking Arkham Horror specifically because I recognize most people would consider it impossibly complex for new players. Whereas, with this approach, I’ve actually found it ideal for introducing new players to theme-rich games.)

Here’s what my introductory spiel looks like. Some of this is visual or physical, so in this text-based format you might need to already be familiar with the game to really follow what I’m talking about. (Fortunately, I’m not actually trying to teach you Arkham Horror; I’m trying to demonstrate how you can break a game down and efficiently present its core components in a way that will easily make sense to new players.)

Welcome to 1920’s Arkham. (point to the board) These are locations and these are streets areas. You can move between these areas by following the lines.

This is your character sheet. At the bottom you’ll see your skills: You can see that each set of skills is paired (Fight and Sneak, Lore and Will, Speed and Luck). You’ll use these sliders to indicate your current level in each skill, trading one against the other. During play, you’ll be able to adjust these values but you can pick you initial value for each skill pair right now. I recommend values in the middle of each range because you don’t really know what you’ll be facing right off the bat.

Note: If you can, get them “hands on” with the game right away. Arkham Horror is great for this because the skill sliders are easy to contextualize and allow the new player to make a meaningful decision less than 30 seconds into your spiel.

You’ll use your skills to make checks. To make a check, you roll a number of dice equal to your skill. 5’s and 6’s are successes. So, for example (roll the dice) on this roll I’ve scored two successes. Generally you just need to score one success in order to succeed on the check, although some checks may be more difficult.

Note: In your spiel you want to drive quickly to the core mechanic and then build up the rest of the game around it. As much as possible you want to avoid saying “I’ll explain that in a minute”. Instead, you want to introduce all the concepts necessary to understand a mechanic before you need to describe that mechanic. This isn’t always possible, of course, but it’s a good goal to strive for because it makes it easier for the new player to build a coherent understanding of how the game works.

Your character also has a special ability, which is described right on your characters sheet.

Note: At this point, I’ll use those special abilities to discuss whatever rules are involved with them. For example, Charlie Kane has an ability related to drawing allies, so I’ll show them the ally cards and point to Ma’s Boarding House on the board. This is useful because it’s personalized and it gives them something concrete to focus on.

The game is broken down into turns. Each turn is broken down into five phases. During each phase, everyone will take their action for that phase in order starting with the first player. Once everyone has gone, we go onto the next phase. Once all the phases are done, the first player token will move to the next player and we’ll start the next turn.

This is our Ancient One: She’s trying to break through into this world and destroy everything. Our job is to stop her.

Note: At this point, I’ll sometimes grab a Call of Cthulhu manual and read the pertinent descriptive text for the Ancient One. It takes a little extra time, but it can help to draw players unfamiliar with Lovecraft into the Mythos.

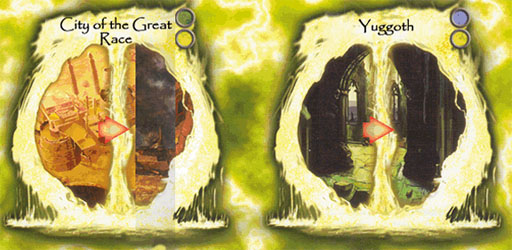

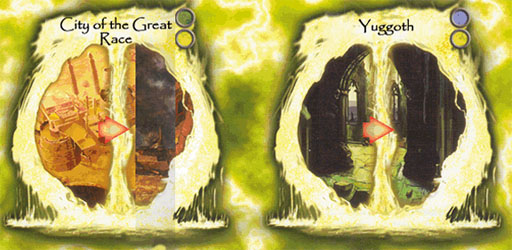

During the game, gates will open between Arkham locations and the Other Worlds. We’ll need to jump through these gates, journey through the Other World, and then close the gates. When we do that, we’ll collect a gate trophy.

There are three ways to win: When we close a gate, we can spend five of these clue tokens to seal it. If we seal six gates, we win. That’s the easiest way to win. Alternatively, if we can close all the gates on the board and we collectively have a number of gate trophies equal to the number of players we win. Finally, if all else fail and the Ancient One awakens, we’ll have a chance to fight them in a final combat. But that’s painful and difficult, so what it really boils down to is that we want to seal gates.

SAMPLE TURN

At this point, the opening spiel is done: Short and simple. The introduction isn’t quite over yet, but at this point we can start actually playing the game while the explanations continue through a sample turn.

Note that the progression to the sample turn only works if the introductory spiel has conveyed enough of the game’s core structure that the players can understand exactly what’s happening during each turn (and why it’s happening). To put it another way, the new player has to be able to make meaningful decisions about the game.

For example, if you were teaching someone Chess and all you did was show them how each piece moves the new player would be able to select a piece on their turn and move it. But they would still lack the understanding necessary to make a meaningful decision about which piece to move and why to move it. (On the other hand, making a meaningful decision doesn’t necessarily mean understanding the deep strategies of the game. A new Chess player who knows that the goal is to put the opponent’s King in check has enough information to make meaningful decisions. They don’t need to know the difference between a King’s Gambit and a Queen’s Gambit.)

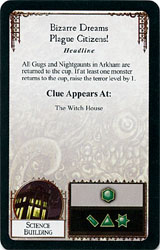

In Arkham Horror you can actually blend the transition between spiel and sample turn a little bit because the last phase of set-up is drawing and resolving a Mythos card (which also happens during play). So let’s draw a hypothetical card now and continue:

(1) Open a gate. We’ll draw a gate token and place it face-up at the location shown on the Mythos card. This gate leads to a specific Other World. (point to that Other World) Whenever a new gate opens, we add a doom token to the Ancient One’s doom track. The Ancient One will awaken when their doom track is full.

(2) Spawn monster. The other thing that happens when a gate opens is that a monster spawns and comes out through the gate. We draw a monster token from this bag over here and place it on the gate.

Note: At this point you might take the time to discuss how you fight monsters. But you can usually wait for that.

(3) Place clue. Next we place a clue token at the location given on the Mythos card. You can pick up all the clue tokens in a location by ending your movement phase on the location. Like we talked about before, you can use five clue tokens to seal a gate. You can also use a clue token to roll one additional die on a skill check.

Note: I use this opportunity to reinforce the basic goal and strategy of the game (“sealing gates”). I might also take the opportunity here to roll another sample check (“For example, if Laura were to make a Lore check she would roll three dice…”) and then demonstrate how a clue token could be used. Finding ways to reinforce/repeat key mechanics, goals, and basic strategies is useful.

(4) Move monsters. If a monster’s symbol appears on the Mythos card, it moves one space following the arrow with a matching color. (For example, on this card hexagon monsters would move along the white arrow.)

(5) Activate Mythos ability. Read the card text aloud. Do whatever it says.

WRAPPING IT UP

And now you’re in the home stretch: Simply walk through the first couple of turns step by step, breaking down each action for the new players. By the end of the second turn, the new players will basically be completely up to speed and fully engaged.

As a final note: You should never tell a new player in a co-op game what they should do. Instead, discuss the strategic situation in the game and present them with options. Let them make meaningful choices. Let them actually play the game.

For example, in Arkham Horror on their first turn might ask, “What should I do?” Don’t tell them something specific like, “Go get that clue token.” Instead discuss broad strategic considerations: “Well, at this point in the game we need to have one or two people collecting five clue tokens each so that they can jump through gates and close them. We also need somebody to fight the monsters to help us keep the board clear for movement. It can also be useful to get $5 and go shopping for an Elder Sign at the Curiositie Shop — that’s an item that will let us automatically seal a gate.” If they decide they want to collect clue tokens and still want more guidance, try to still present them with multiple tactical options: For example, you could show them three different locations that they could move to in order to pick up a clue token and then let them decide which one they want to go to.

For Arkham Horror, I’d also recommend the Arkham Companion app for Android devices. It’s compatible with all of the expansions and completely automates Arkham location and Other World location cards, which massively declutters the table and simplifies game flow. You can read all about it on the FFG forums and you can grab it from either Google Play or Dropbox.

To make a long story short: Legends & Labyrinths is simply the most blighted project I have ever worked on.

To make a long story short: Legends & Labyrinths is simply the most blighted project I have ever worked on.