“If you were teaching a intro-level college class on roleplaying game design, what would be the reading list?”

Interesting question.

I’m going to design this as a survey/history course. And you’ll need to snag copies of these at the campus bookstore:

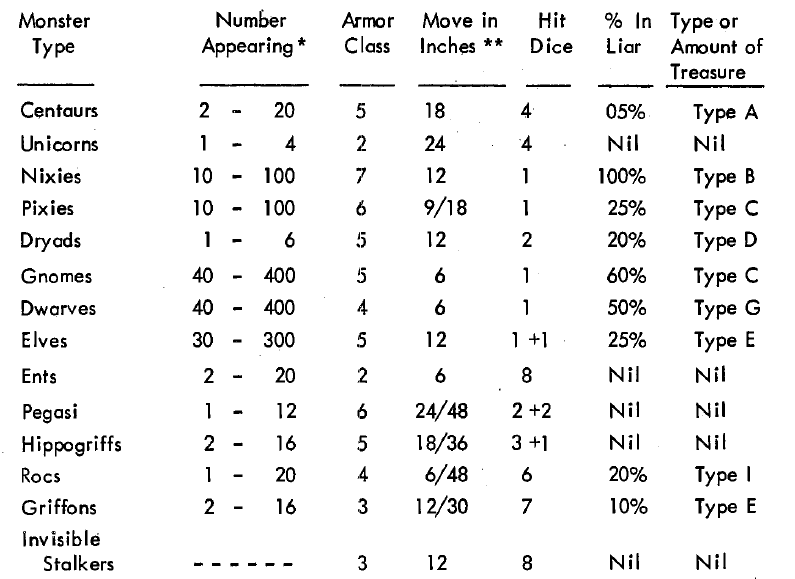

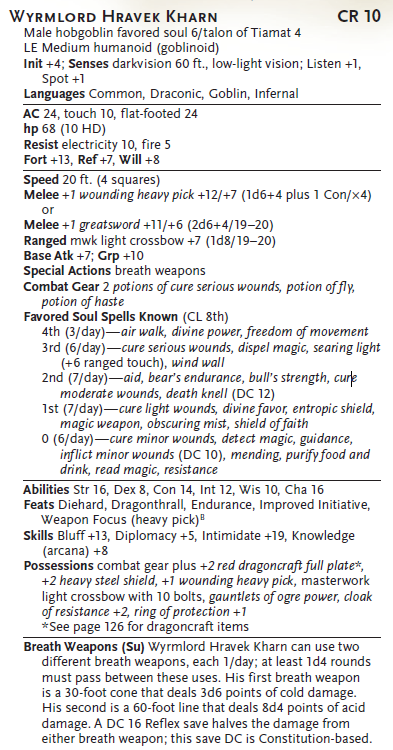

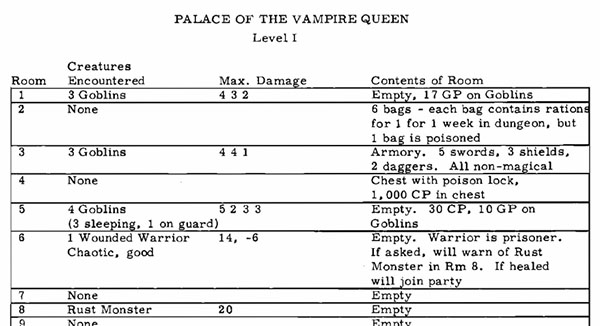

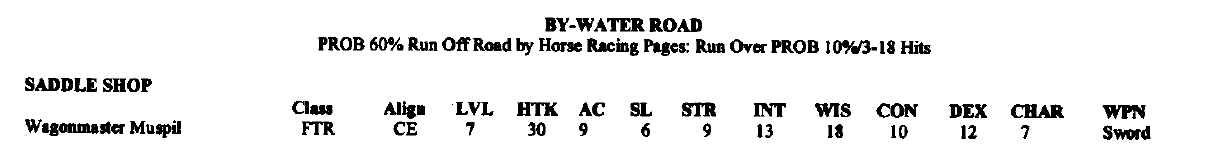

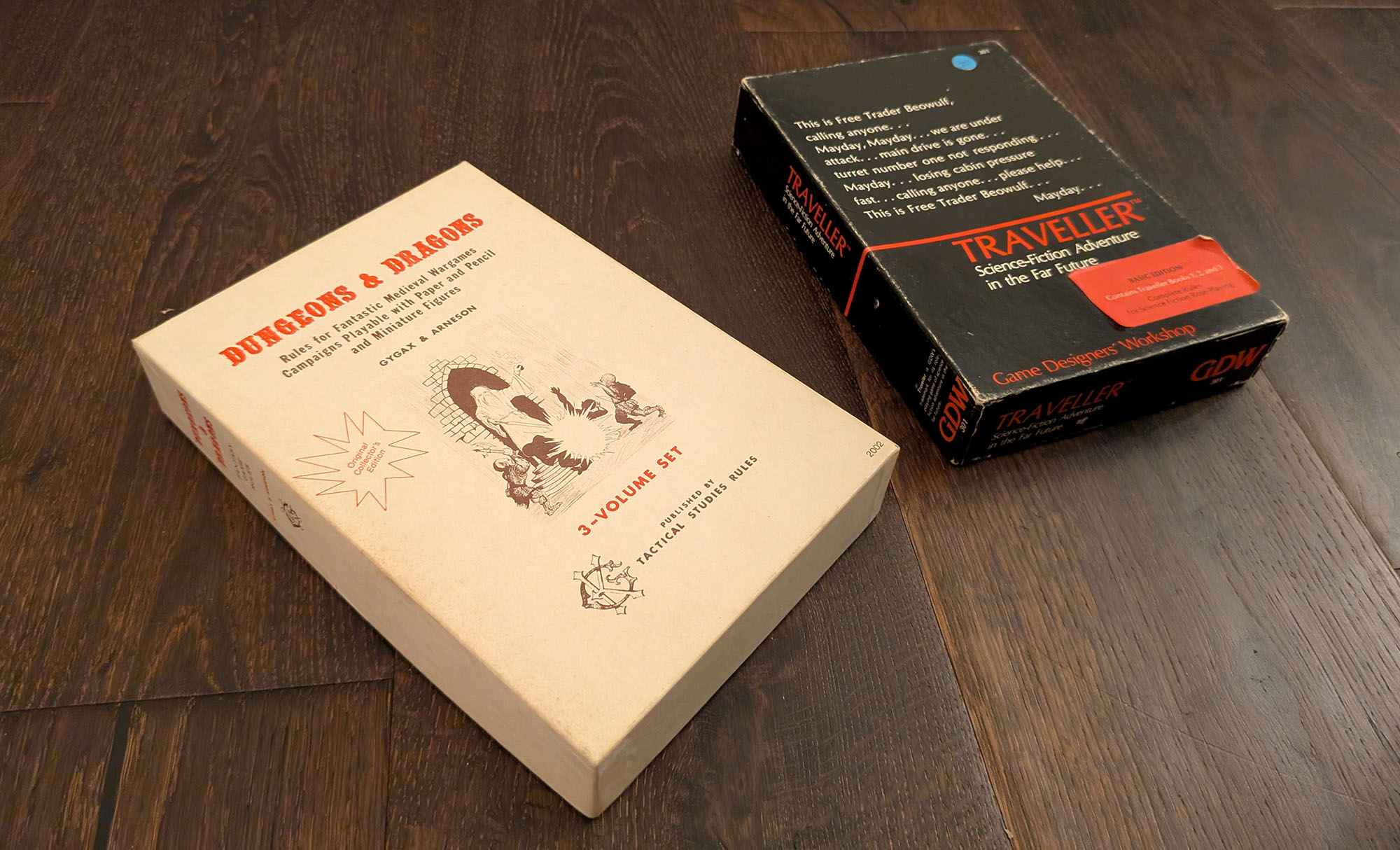

1974 D&D

Traveller

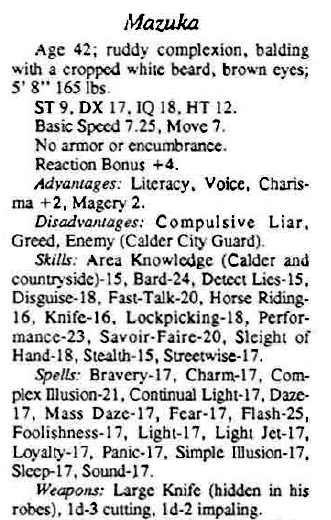

GURPS or Champions

Paranoia (1st Edition)

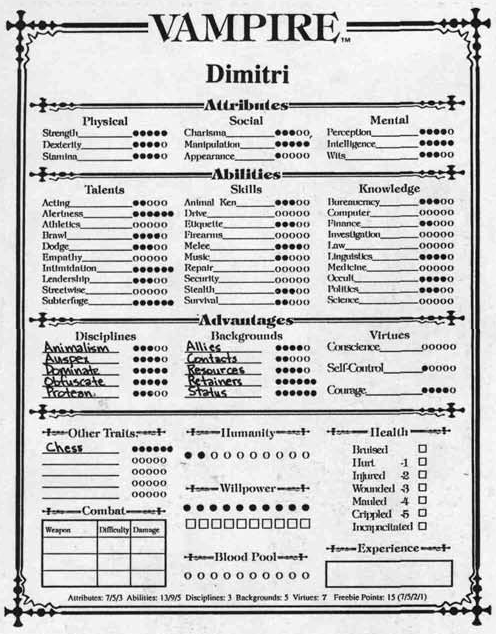

Vampire the Masquerade

Amber Diceless Roleplay

Burning Wheel

Apocalypse World

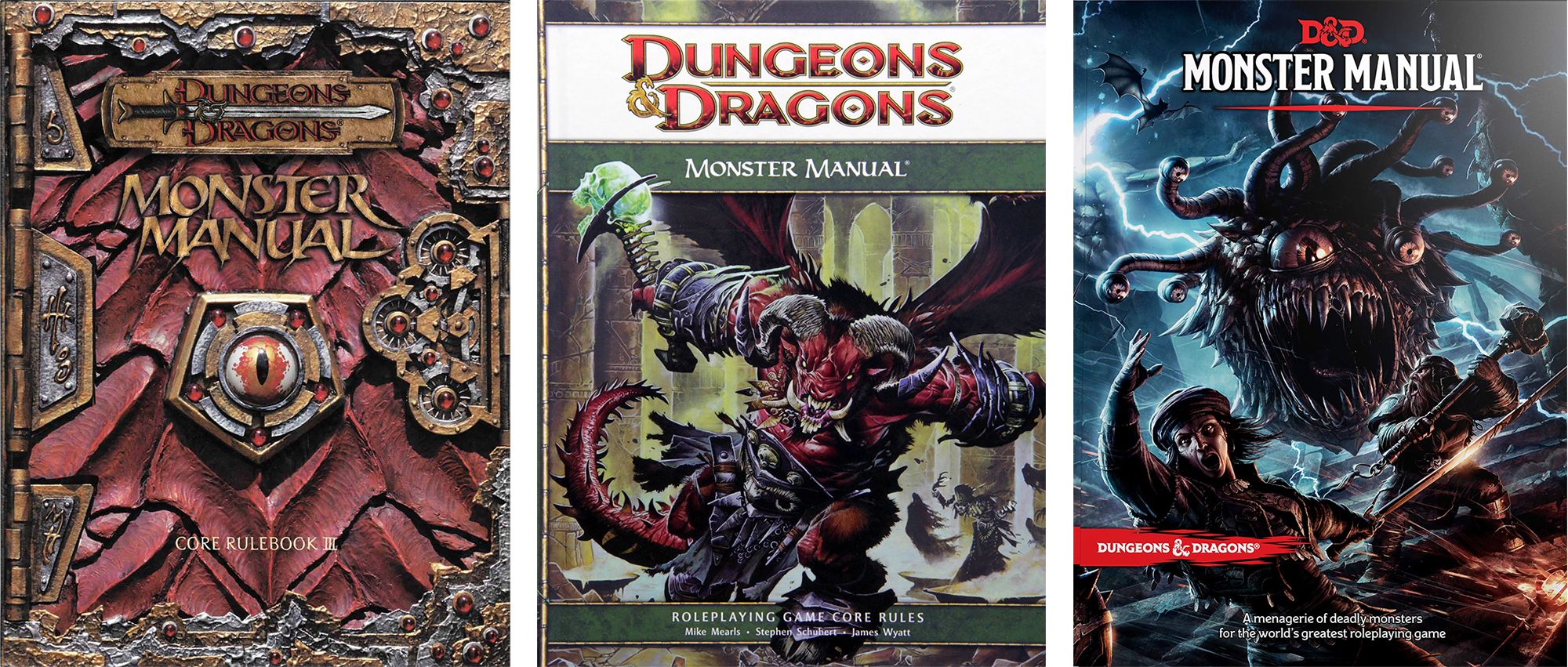

And we’ll wrap the course up by comparing D&D 3E, 4E, and 5E, with a particular focus on how they responded to design trends.

D&D 1974

This is the beginning. The baseline for everything that follows and a frame for discussing the proto-history and origin of RPGs from Kriegsspiels to David Wesley to Dave Arneson.

TRAVELLER (1977)

Traveller does triple duty for me.

- It gives insight into the first generation of RPGs that were responding to D&D.

- One of the first science fiction RPGs, after Starfaring and Metamorphosis Alpha.

- Includes a Lifepath system, giving us a first step in looking at different approaches to character creation.

GURPS / CHAMPIONS

(’80s Editions)

The birthplace of the well-supported generic/universal RPG system.

A central thesis of this class will be that RPGs pretty universally pushed for “accurate simulation” as a primary design goal through the late ‘70s and ‘80s. Whichever one of these games we choose to look at it will serve as a great exemplar of that trend.

It will also give us point-buy character creation in its fullest flower, allowing us to clearly show the difference between character generation in 1974 D&D and the character crafting which would come to largely dominate the hobby.

PARANOIA

(1st Edition)

This is kind of an oddball choice. Every intro class has one of these on the reading list, right?

But it’s here for a reason.

On the one hand, Paranoia is a comedy game, which gives us a nice, sharp look at the emerging diversification of creative agendas in the ‘80s.

On the other hand, it also examines the unexamined “simulation = good” trend in the ‘80s. Paranoia is a lighthearted comedy game, but its first edition features, among other things, a Byzantine three-tier skill specialization system, because “simulation = good” even if it made no sense for what the game was actually trying to achieve.

(I will give extra credit to any student arguing that the incredible minutia of the system was actually part of the satire of a Kafkaesque government bureaucracy. They’re wrong, but it shows they’re thinking critically about this.)

WHITHER THE UNIVERSAL SYSTEM?

Universal RPGs were VERY popular in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and then they weren’t. There are still some around today, of course, but the only truly popular ones are 20+ years old.

One theory is that the niche was definitively filled by GURPS, and no other universal RPG could ever compete with GURPS’ library of support material.

The other is that universal RPGs were at their strongest because of the “simulation = good” paradigm. Once you move past the idea, as demonstrated in Paranoia, that “good system” is a Platonic ideal divorced from a game’s creative agenda, the appeal of a “universal system” is not eliminated, but significantly diminished.

VAMPIRE: THE MASQUERADE

This brings us to Vampire: The Masquerade, a hugely important game that grappled mightily with the idea of pushing a creative agenda other than simulation.

The Storyteller system is interesting to analyze because (a) it ultimately fails to achieve its storytelling goal (and analyzing failure is a great way to learn) and (b) it’s virtually impossible to understand GNS theory without the context of Storyteller.

AMBER

Before we get to GNS, though, Amber Diceless Role-Playing will be our exemplar of the snap-back against detailed simulation.

Emphasized by its diceless engine, Amber was one of many early ‘90s games that were fed up with complexity and bounced to the opposite extreme. It’s an elegant tour de force for designing mechanics customized to the creative agenda and setting of the game.

Plus, Amber features alternative structures for organizing campaigns and extending player beyond the session. So we’re getting a lot of mileage from this one title.

BURNING WHEEL

There are a lot of Forge-era indie games we could choose to spotlight GNS theory. One could argue that we should go with a game by Ron Edwards or D. Vincent Baker. (We’ll cover the latter with Apocalypse World.)

Burning Wheel is, ultimately, just a better game and synthesizes a wider range of innovations. So that’s what I’m tapping.

APOCALYPSE WORLD

Which brings us to Apocalypse World.

Powered by the Apocalypse is the single biggest non-D&D influence on RPG design in the last fifteen years, so it’s basically essential. And, as I just mentioned, D. Vincent Baker is a seminal figure and his design philosophy should be highlighted. So this is another game that’s doing double duty.

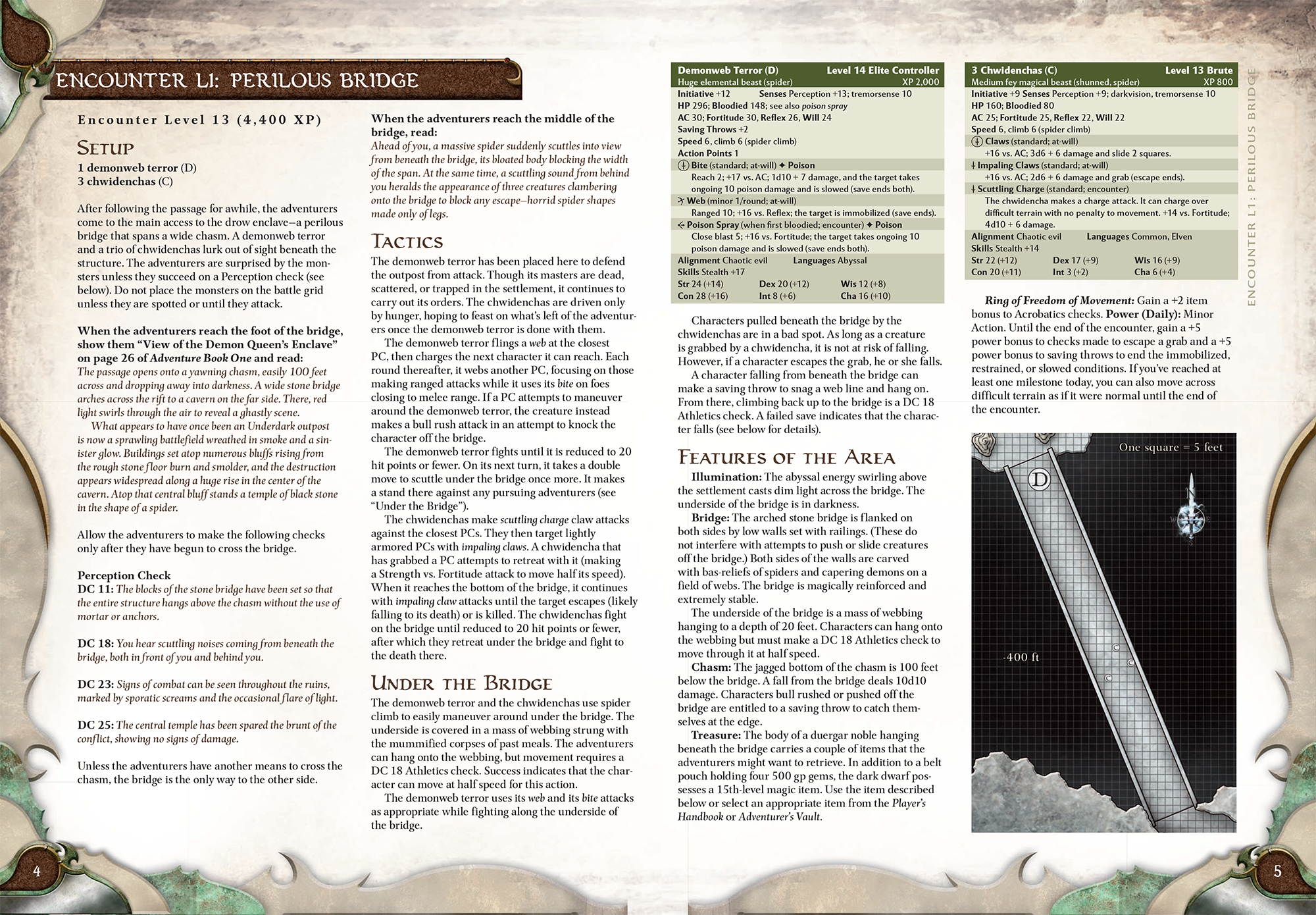

WotC-ERA D&D

The big wrap-up for our course is a comparison of D&D 3E, 4E, and 5E.

D&D is, of course, the 10,000 lbs. gorilla in the RPG design room. If we’re teaching an intro course, we absolutely need to cover its evolution.

Post-1974, however, D&D has been extremely reactive in its design. It largely does not innovate, but its massive gravity means anything it refines is reflected back into the industry in a massively disproportionate way. (Take, for example, the concept of advantage/disadvantage as modeled by rolling twice and taking the better/worse result. This was an exceptionally obscure mechanic pre-2014, but after D&D 5E used it, you can find it everywhere.)

Having broadly covered the history of RPG design, therefore, looking at how D&D reacted to (or didn’t react to) those design trends is a great way to review and critically analyze everything we’ve learned in the course.

The final list also gives us (coincidentally, I didn’t actually plan this) wo games from each decade (‘70s through ‘10s) with an extra dollop of D&D. That’s a good gut-check to make sure I wasn’t getting too biased in my selections.

NOTABLE ABSENCES

There are a few notable things missing from this reading list.

FATE, which had a massive influence in the decade before Powered by the Apocalypse, serving as the system for any number of games.

Storytelling Games. Only peripherally looking at how STGs have influenced RPG design is iffy. You can easily make a case for throwing in Once Upon a Time or Microscope or Ten Candles.

RPGs in a Box. These are games like Arkham Horror, Gloomhaven, and Descent. They aren’t actually RPGs, but they’re in the same design space.

Starter Sets. There are unique design considerations in making an effective starter set, but we didn’t cover them at all.

Organization-based Play. This would be a game like Ars Magica, Blades in the Dark, or Pendragon. This has been a persistent design goal for RPGs since Day 1. I can touch on it a bit with Traveller, but it’s really exploded in the past decade and not having a more recent example is a limitation.

Call of Cthulhu. Just because it’s Call of Cthulhu. But my goal wasn’t Most Important RPGs (Call of Cthulhu is easily Top 5), it was Introduction to RPG Game Design. There’s stuff that I could use Call of Cthulhu to teach, but not enough hooks to knock others off this list.

After all, there are only so many hours in a semester.

FURTHER READING

It’s Time for a New RPG

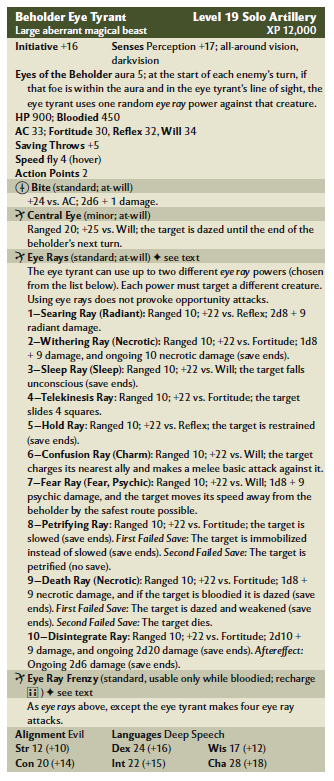

A History of Stat Blocks