DISCUSSING

In the Shadow of the Spire – Session 27A: The Midnight Meeting

“By coming here, you have already joined this Brotherhood,” Dilar continued. “Over the next few weeks you will be contacted. For many of you there will be training. You will be asked to do things. Many of these things will seem simple or even unimportant, but you should never doubt that in even the smallest service you are aiding the Brotherhood and all that we are attempting to accomplish.”

If you’re a long-time reader of the Alexandrian, you’re probably familiar with the Three Clue Rule: In a mystery scenario, for any conclusion that you want the PCs to make, you should include at least three clues.

This redundancy makes mystery scenarios robust, so that they don’t break down during play and leave either you scrabbling frantically, your players frustrated, or both. In my experience, the process of fleshing out a scenario to support the Three Clue Rule also usually results in a more dynamic and interesting scenario.

When I’m prepping a module, therefore, I make it a point to check each revelation and make sure that the Three Clue Rule is being observed. For published adventures, unfortunately, this often isn’t the case, and I’ll need to add clues. Session 27 of In the Shadow of the Spire is a good example of this.

Many of the events detailed in this session — the secret meeting and project site — are from Monte Cook’s Night of Dissolution mini-campaign. A key revelation is, in fact, the location of the project site. From the secret meeting, the published adventure includes one clue pointing to that revelation:

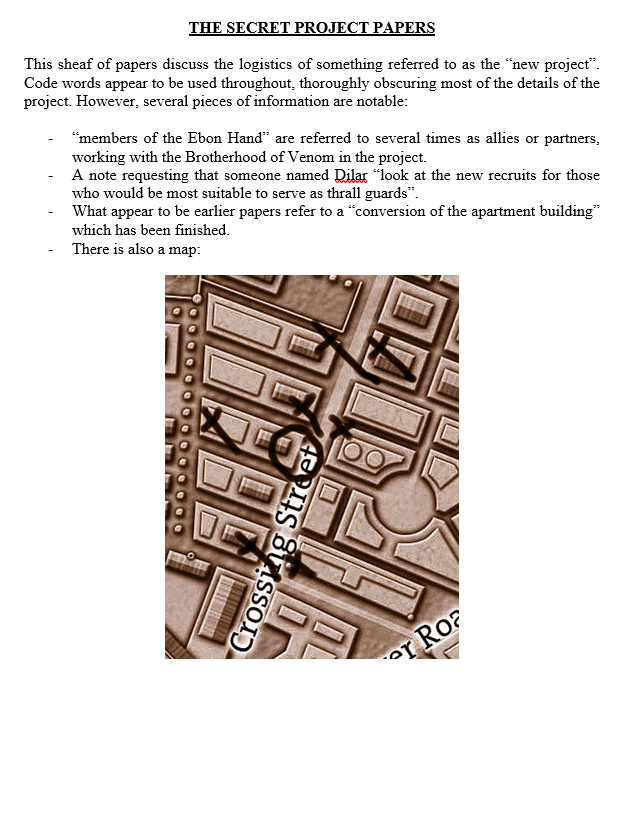

Dilar has a number of papers and notebooks with him. […] Among other things, the papers show the location of the Brothers of Venom’s secret project: an apartment build in Oldtown off Crossing Street. The documents refer to the building only as the “secret project” or the “joint project,” however. (The address can lead them to the Temple of Deep Chaos, found in Chapter 4.) The pages also discuss the cult’s new allies, the Ebon Hand cult, and mention that cult’s leader, Malleck, and their activities involving kidnapping young people and transforming them.

(You can also see here a secondary revelation — the alliance with the Ebon Hand — which is non-essential.)

Seeing this, the first thing I did was prep Dilar’s papers as a physical handout that I could give to the PCs.

You can see that this is not particularly elaborate, being a fairly simplistic example of the lore books technique we’ve discussed previously. The primary goal here is just to let the players “shuffle through the papers,” rather than listening to me narrate them. The map here also neatly correlates to the map of the city hanging on the wall during our sessions, so the players would’ve been able to take this handout over to the map and literally figure out where they needed to go.

As it turned out, however, the players never actually got this handout. Which is why the next thing I did was so essential: Adding additional clues to support the revelation.

To the adventure’s credit, it does discuss multiple paths by which the PCs might come into possession of Dilar’s papers: They might, for example, kill him and loot them. Or they might bloodlessly infiltrate the meeting, take the opportunity to surreptitiously peek at his papers, and then get out without the cult being any the wiser.

But these routes still all go through Dilar’s papers, creating a chokepoint that makes the scenario fragile. You can see that in actual play here: Because of how events played out, only one PC infiltrated the meeting, making the “kill all the cultists and loot their stuff” outcome basically impossible. Tee was also well aware of how vulnerable she was, meaning that she didn’t want to take any risky actions that might expose her (e.g., looking at papers she shouldn’t be looking at). If I’d run the adventure as written, it would have broken here.

What I needed to do was create additional vectors leading from the secret meeting to the project site. (Alternatively, I could have gone for a node-based approach, adding clues to the secret meeting pointing to cult-stuff other than the project site, and then seeded additional clues to the project site in those other nodes.) My thought process went something like this:

- Well… what is the actual purpose of this meeting?

- What if it’s to brief cult members on the project site? That would also explain why Dilar is bringing notes detailing the project site to the meeting.

- We know that this meeting includes new recruits. They’re not going to be fully read in on the project. (Which is convenient logic, because otherwise all of the scenario’s revelations would get frontloaded into this single scene instead of being slowly peeled back by the PCs over the course of their investigation.)

- What would the cult be asking new recruits to do that might be related to the project?

- They could be assigned as external security/lookouts!

This immediately gives me two new clues:

- The PCs can infiltrate the meeting and get briefed on the contents of Dilar’s notes.

- The PCs could question Iltumar about what he learned at the meeting.

And then, by having the cult members taken directly from the meeting to the project site, I can add another clue:

- Following cult members leaving the meeting will lead PCs to the project site.

While this took a little bit of thought, one thing to note here is how little prep was actually required. This is often the case. In my experience, it takes virtually no effort and a truly minuscule amount of time to add basic clues to a scenario. That’s because clues are just indicators. The meat of the scenario — the stuff you’ll spend the bulk of your prep time on — is what the clues point at.

(The most common exception to this is when you design a handout for the clue, like the lore book for Dilar’s notes. But this is usually not, strictly speaking, necessary, and the time you’re investing there is more in the value-add of the cool handout than it is in the clue itself.)

Despite the relative ease of adding these clues, also note how much depth we’ve added to this scenario. For example, the original adventure only told us:

The cultists are here to plan further murders, trade advice on poison use, and engage in perverted sexual acts.

But we now have a much more specific agenda for the meeting. The natural interrogation of the scenario that happens when we think about the vectors required for clues means that we now understand the what and why of the cultists here. So if the PCs were to eavesdrop on the meeting or, as it turned out, infiltrate the meeting, we have a much firmer foundation to stand on for improvising the scene.

As I say, this happens all the time when you apply the Three Clue Rule in your scenario design.

The other thing you’ll discover is that missed clues will no longer be something that you fear. This can feel weird, but it’s incredibly liberating. For example, if this scenario had still depended on Tee looking at Dilar’s notes, I would have felt the need to reassure her that it was OK to sneak a peek. I would have needed to find some direct or indirect way of letting her know that she didn’t really need to be afraid of exposing herself and getting caught.

But because I knew that I’d made the scenario robust, I didn’t need to do that. The result was a vastly better scene, in which the tension of discovery drove the stakes from beginning to end. It would have been a shame if I’d felt a need to deflate that tension in order to prevent the scenario from breaking.

And this is, again, something that happens all the time when you’ve got the Three Clue Rule backstopping you. Missed clues are no longer catastrophes; they are a vital part of the scenario’s flow.

If you haven’t experienced this firsthand, it can feel paradoxical. It might even feel like a violation of the principles of smart prep: You have this prepped content that you’re not using! It’s wasted! But, in practice, missing a clue isn’t a waste — it’s a consequence, a cost, or a choice. And even if you have a clue that is “wasted,” it’s not that big of a deal because, as we noted before, the clues are mostly ephemera. They aren’t the meat of the scenario.

NEXT:

Campaign Journal: Session 27B – Running the Campaign: Improvising Floorplans

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index

Ah! Thank you, it’s always exciting to know what was happening behind the recap.