Ten years ago I wrote Xandering the Dungeon, a detailed look at the differences between linear and non-linear dungeons. In this essay I briefly used what I dubbed Melan diagrams — a technique created in 2006 by Melan for a thread on ENWorld where he discussed “map flow and old school game design.”

These diagrams are, unfortunately, not immediately intuitive to everyone looking at them, and because I used the diagrams in Xandering the Dungeon, I’m frequently asked how they’re supposed to “work.” In fact, I’ve been asked that question three different times in the last week… which brings us to today’s post.

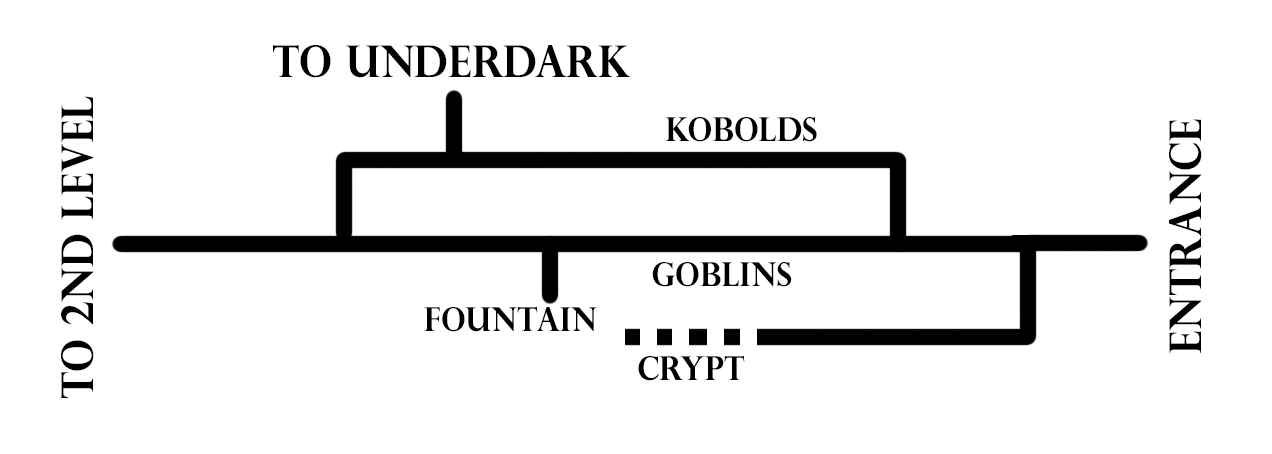

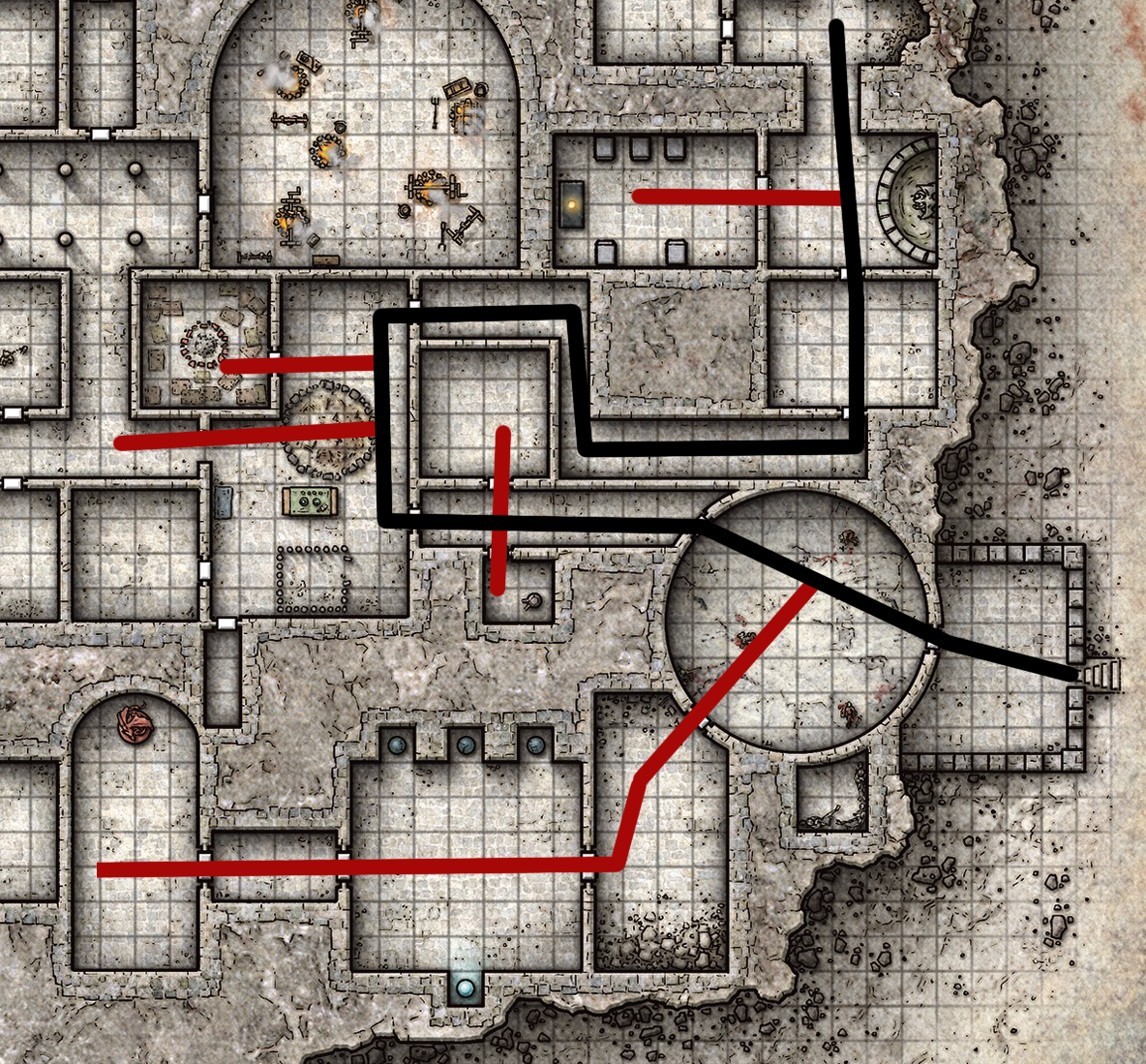

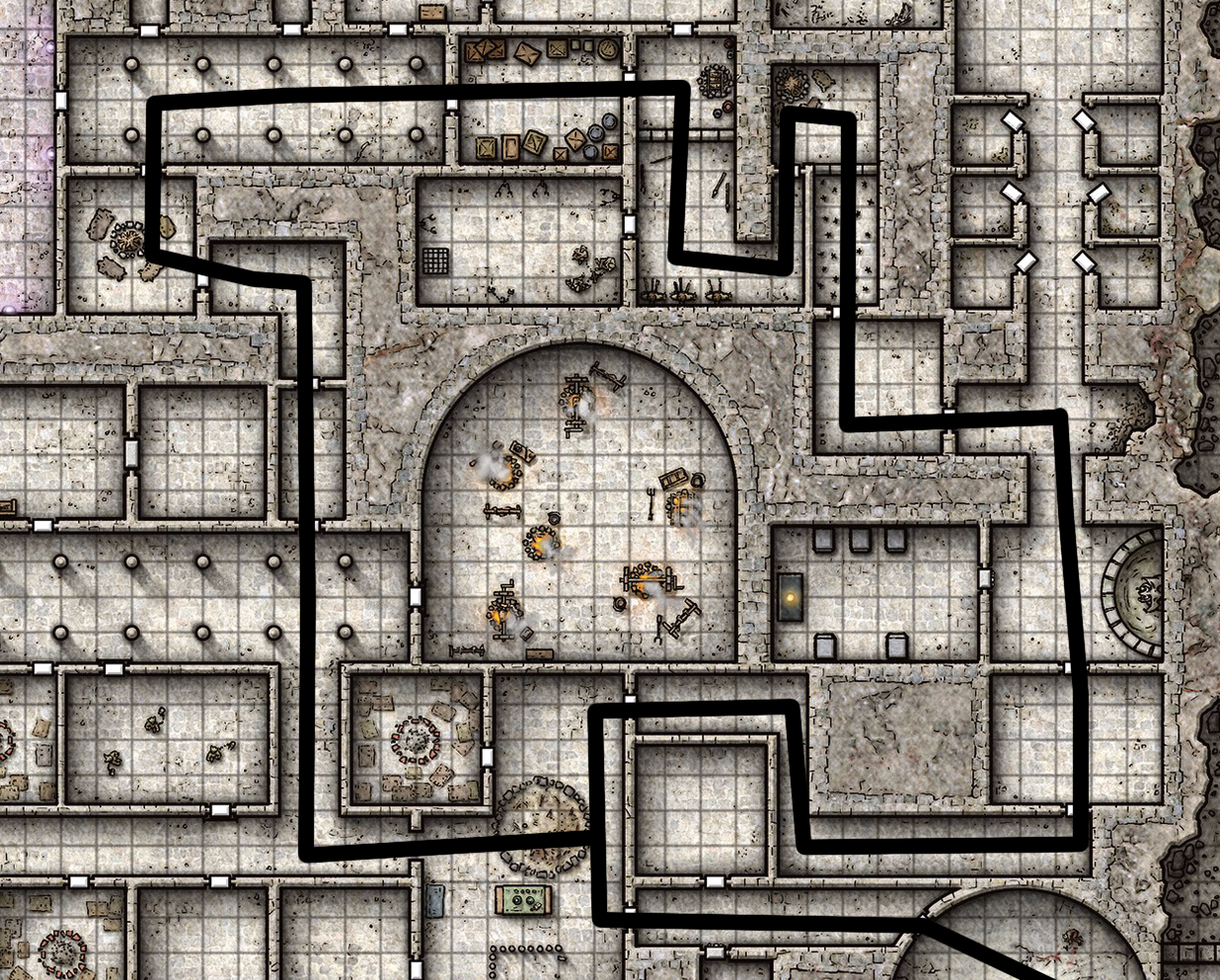

You can see an example of what a Melan diagram looks like at the top of this post. It depicts the first level of The Sunless Citadel, designed by Bruce Cordell with original cartography by Todd Gamble. (Today, though, I’ll be using Mike Schley’s version of the map from Tales From the Yawning Portal.)

So… what’s the point of this thing? Well, as Melan said in his original post:

[They are] a graphical method which “distills” the dungeon into a kind of decision tree or flowchart by stripping away “noise.” On the resulting image, meandering corridors and even smaller room complexes are turned into straight lines. Although the image doesn’t create an “accurate” representation of the dungeon map, and is by no means a “scientific” depiction, it demonstrates what kind of [navigational] decisions the players can make while moving through the dungeon.

By getting rid of the “noise” you can boil a dungeon down to its essential structure. They also allow you to compare the structures of different dungeons at a glance.

It’s fairly important to note that you don’t actually use Melan diagrams for designing dungeons. They are an analytical tool, not a design tool: You use them to look at something which has already been created, not to create it in the first place.

But if you’re looking at a diagram what does it actually mean? How is the noise being stripped out and what does that tell you? How are you supposed to interpret the diagram? Or make one for yourself?

STRAIGHTEN THE LINE

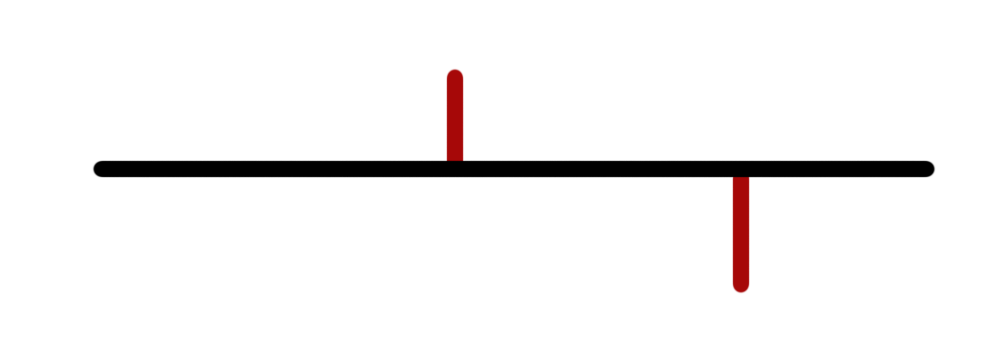

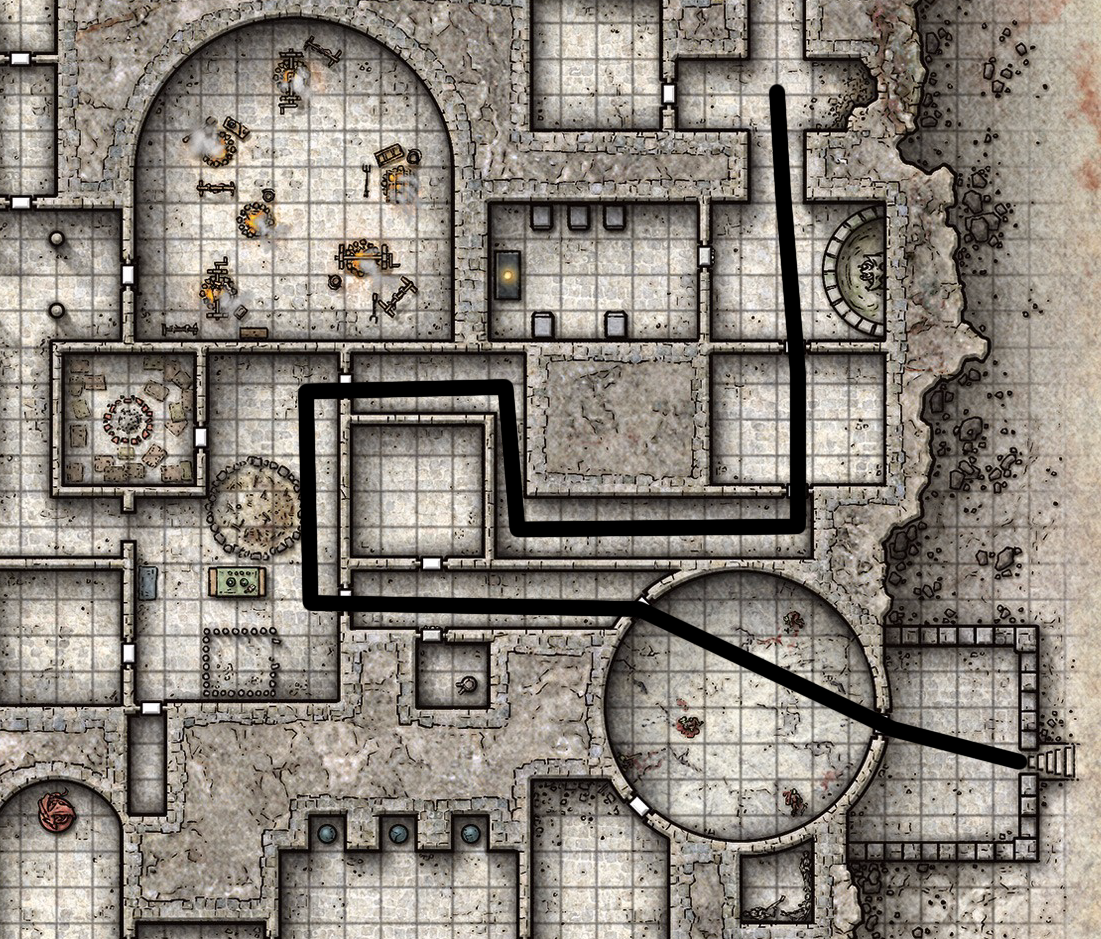

The first principle of making a Melan diagram is to eliminate all the irrelevant twists-and-turns on the map. For example, consider this path through the Sunless Citadel:

It looks really interesting, right? All kinds of turns. You went through multiple doors. You even reversed direction a couple of times!

But as far as the Melan diagram is concerned, this is a straight line: Following a corridor when it makes a turn isn’t a meaningful navigational choice. Same thing for going through a door if there’s no other exit from the room.

FORK THE PATH

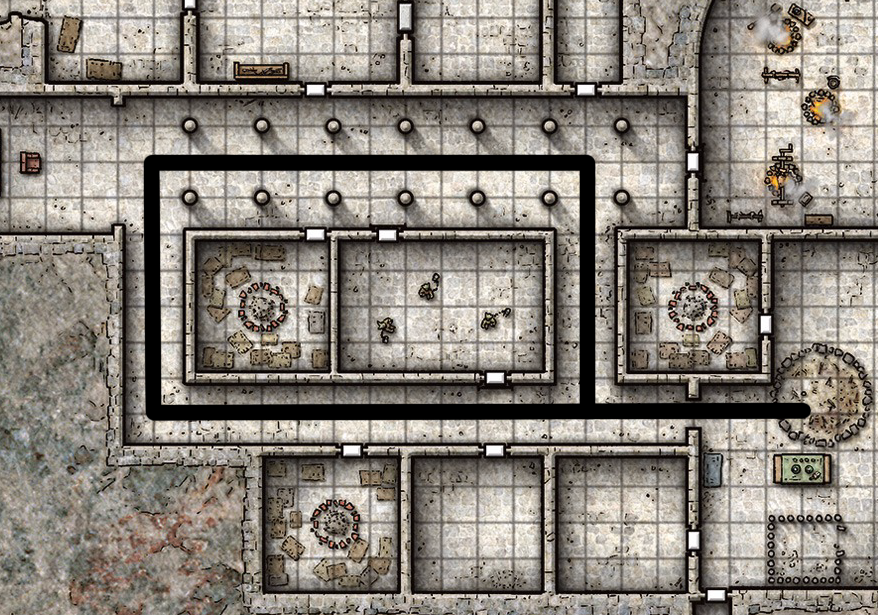

“But wait a minute!” you say. “In following this path the PCs did make choices! For example, in that first circular room the PCs had the choice of two different doors!”

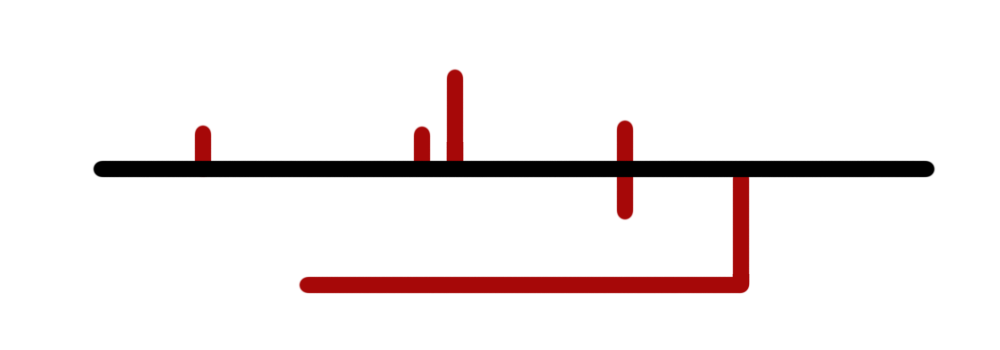

You’re absolutely right! This is exactly what a Melan diagram is interested in looking at. On this little chunk of the Sunless Citadel, there are two forking paths:

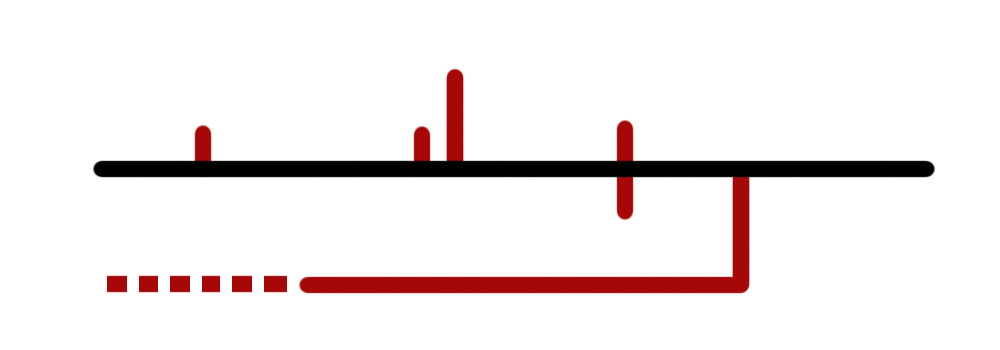

And so, on a Melan diagram, this section would look like this:

The black path is depicted as a straight line and the alternate paths are shown in red. (Melan diagrams typically aren’t color-coded like this since all paths are equally valid. We’re using the colors here for clarity.)

The length of each branch of the diagram, it should be noted, is roughly proportional to its length in the dungeon. (I don’t carefully measure this or anything, but you could if you wanted to.) In this case I’m showing them proportional per the section of map we’re looking at. (As we’ll see in a moment, these particular spurs are actually much longer.)

ELIMINATE SIDE CHAMBERS

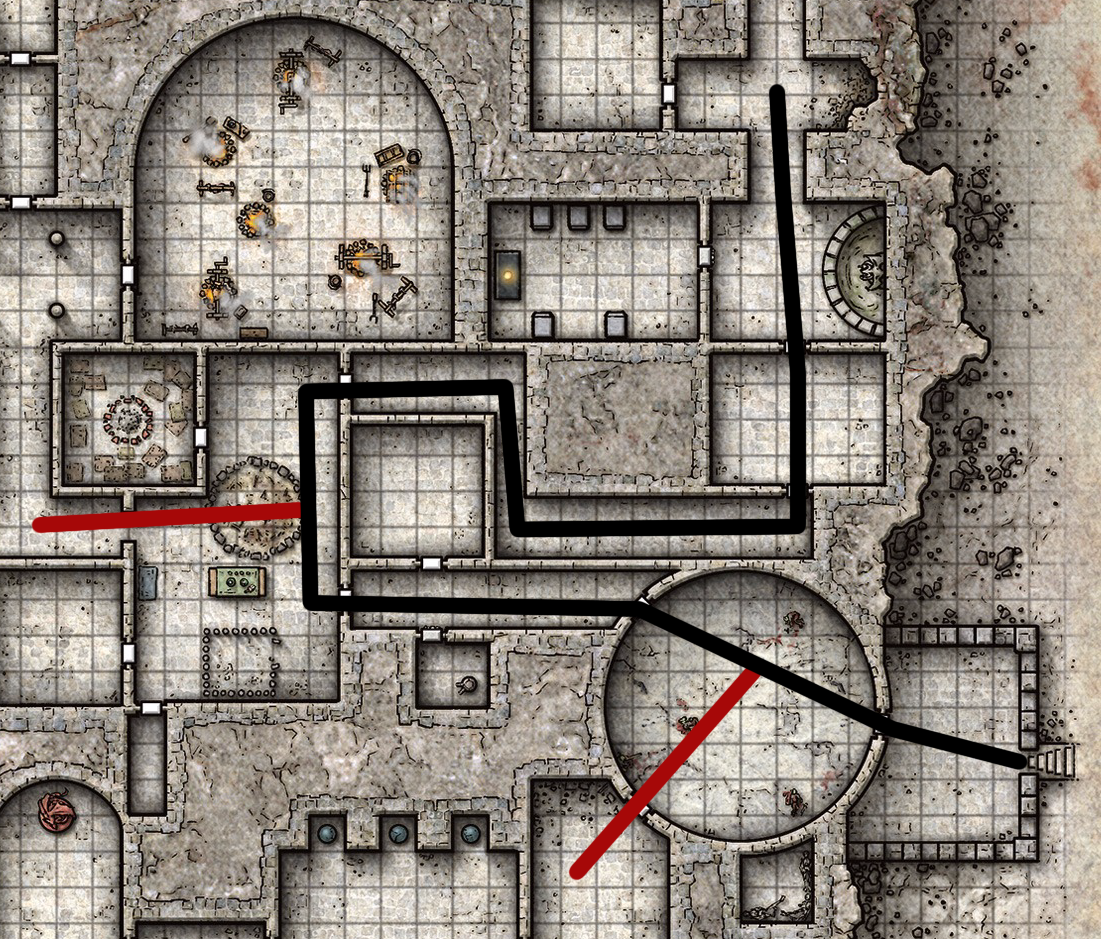

“Wait another minute!” you cry. “I can see other doors that you’re ignoring!”

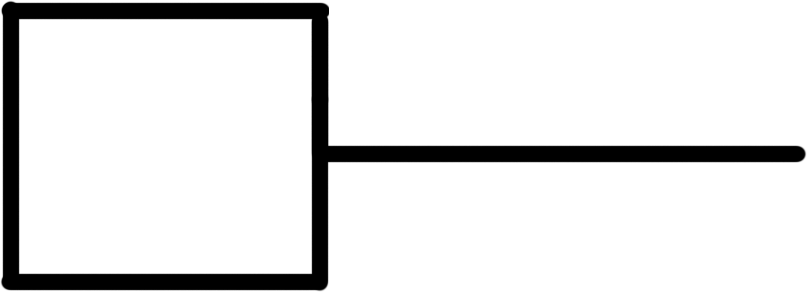

The second principle of a Melan diagram is that we are going to eliminate all paths that are only one chamber deep.

So we could take this chunk of dungeon:

And draw a diagram like this:

But the reason we don’t do this is because such a diagram becomes meaninglessly noisy. Furthermore, these side chambers largely don’t represent meaningful navigational choices on the macro-level of the entire dungeon: You might choose to bypass such doors, but if you open one of them the only “choice” is to go back to the path you were already following.

Note that you can actually see this when looking at the diagram: It’s immediately apparent that all those little spurs don’t really “go” anywhere.

(You can argue that the same thing is technically true of longer sidetracks, but in practice these longer paths tend to be more meaningful to the overall structure of a dungeon and the experience of playing it. With that being said, there’s nothing magically relevant about one room vs. two rooms and in larger dungeons you may find different thresholds for what constitutes a “meaningful sidetrack” to be useful.)

You’ll similarly want to eliminate very short dead end hallways if they exist.

DIAGRAMMATIC TURNS

“Hey! What’s with that turn in your diagram? I thought you said we weren’t mapping that sort of thing!”

That’s true. In practice, however, Melan diagrams will introduce superfluous ninety-degree turns in order to keep the diagrams relatively compact or to conveniently make room for other paths.

So if you see a turn on a Melan diagram that doesn’t have a second path branching from it, you’ll know that it’s purely cosmetic. It doesn’t actually reflect a “turn” in the dungeon; and, although the turn in our current example sort of resembles a turn in the dungeon itself, such turns on the diagram may be present even when there are no turns in the corresponding dungeon tunnel.

ELIMINATE FAKE LOOPS

Dungeon paths will, of course, form loops. In fact, a well-designed, xandered dungeon will probably feature LOTS of loops. Ignoring routes that branch off from the loop for the moment, here’s one from the Sunless Citadel:

On the Melan diagram, it would look like this:

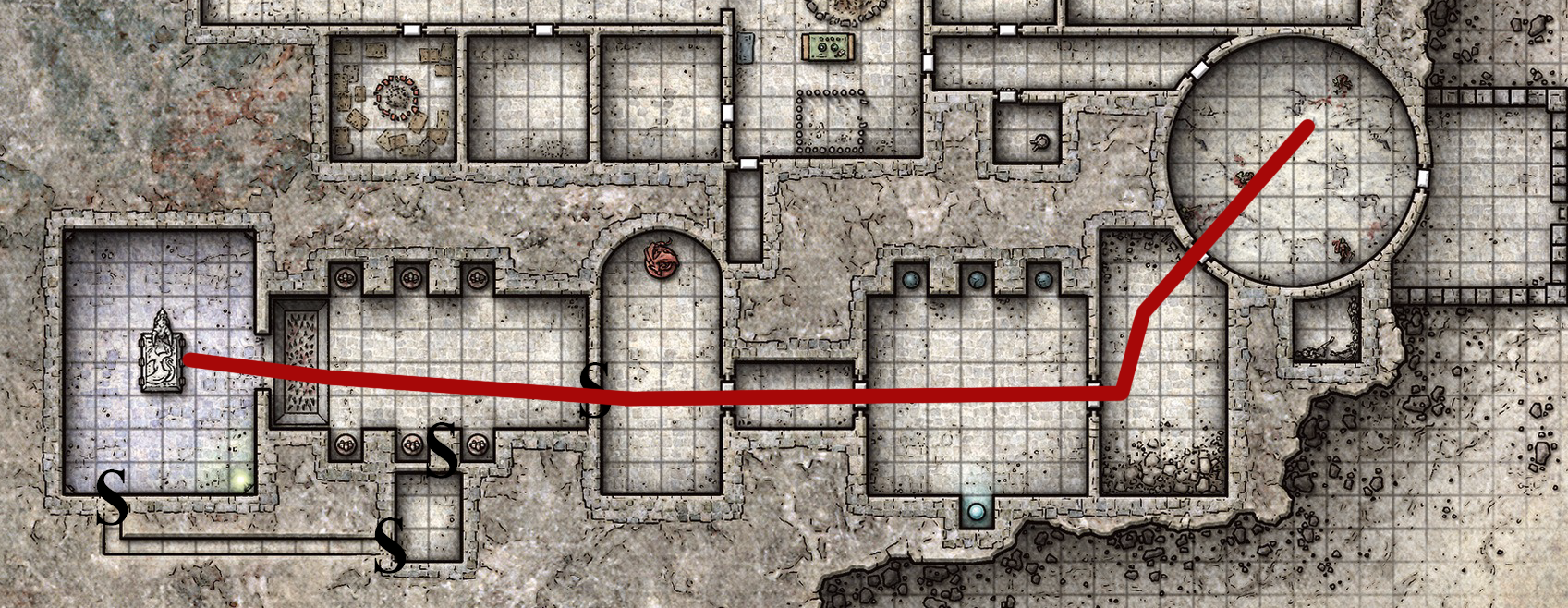

But what about this loop?

Well, on a Melan diagram this would actually be depicted as a straight line. To understand why, let’s start by eliminating the side chambers:

Viewed like this, you can clearly see that this is not a true navigational loop: It’s a fake fork. The navigational “choice” is a false one. After eliminating the side chambers, both paths lead immediately to the exact same place.

SECRET PATHS

When a path like this one goes through a secret door, this is indicated with a dotted line on the Melan diagram:

(Note that the other secret doors are not represented here because they lead to side chambers, which are eliminated regardless.)

An area is ONLY depicted as secret on the Melan diagram if the ONLY way of reaching that area is secret. However, even a secret door that leads directly from one “public” area to another would still be shown on the diagram as a short dotted line. (The secret path exists and is significant, even if the “length” of the path is only the width of the secret door itself, so to speak.)

LEVEL CONNECTIONS

The last functional element of a Melan diagram are the connections between levels. When a path goes from one level of the dungeon to another (by stair, elevator, sloping ramp, teleporter, or whatever), this is indicated by a break in the line with terminating lines on either side:

OTHER ELEMENTS

Melan diagrams may also include labels (e.g., “Goblins” or “Secret Lab” or “Teleportation Trap”). These are technically non-functional parts of the diagram, but can be useful to help readers orient themselves.

Some Melan diagrams of long, linear dungeons will be split into multiple columns, with the connection between the columns being indicated by a dotted line with an arrow. (This is sometimes confused for a secret door, but it’s really just a tool for keeping the diagram relatively compact.)

CONCLUSION

If you’re reading this and still scratching your head over what the point of any of this stuff is supposed to be or what relevance the elements depicted by a Melan diagram are supposed to have, I’m going to do a full loop here and refer you back to Xandering the Dungeon, which is designed as an introduction to the sort of basic dungeon design techniques that the diagrams are designed to demonstrate.

I’d suggest referring confused readers to subway route maps, as they similarly simplify the twists and turns of subway lines into straight lines, with bends used mostly for space or practical concerns, not to follow the real world geography.

This was great, and a good rundown of a strong tool to keep under our belts. Have you seen the YouTube series Boss Keys? The creator eventually has his own breakdown of Dungeons and their design that follows a similar flow-chart kind of method he refines as time goes on. While electronic dungeons aren’t ever the same as table-top ones, I find understanding structure and design elements helps me for if and when I choose to steal boldly for my own design purposes.

@Dennis: Great example!

@CryptThing: I haven’t seen that, but sounds like I need to check it out! Thanks!

While I understand (and agree with) the logic of reducing useless loops into a straight line, the example you give is unfortunately not quite clear-cut. One of the side rooms has two doors, connecting the corridor with the columned hall, thus forming a qualitatively different path between those two places. Assuming there is content in that side room, it would form a meaningful navigational decision.

Concerning the elimination of side rooms in general, it’s probably best to adjust it based on the size of the dungeon. If you have a five-room cave, then the diagram won’t be very large in the first place and the side rooms can be left in (and likely have content in them justifying them being left in). If you’re trying to understand a ten-map megadungeon, you should probably start pruning side paths and one-room loops heavily because that’s just not the scale you’re looking at.

I’ll also note that I have used (annotated) Melan diagrams for dungeon design. I think however that a flowchart method will probably be more useful, especially for beginners.

Why not use them as a design tool? Seems quite useful in the overview stage when designing a scenario, making sure there is enough connections between different elements.

Ah, and I realized now that this is the same Melan as Gabor Lux of Beyond Fomalhaut 🙂

You said that you don’t actually use Melan diagrams for designing dungeons. What is the method you recommend to map one from scratch?

You say “you don’t actually use Melan diagrams for designing dungeons,” but it seems like it would be a good idea to keep your Melan diagram in mind while you’re doing it!

Even if it’s an iterative step, like: start with a block diagram (goblins here, oozes there), add connections, draft a map, check the Melan diagram, improve the map, repeat.

@Pelle, agreed, and in fact I think that *this* is actually an example of using a Melan diagram as a design tool. (The design stage being “revision” rather than “blank page” doesn’t mean it’s not design!)

https://thealexandrian.net/wordpress/44474/roleplaying-games/remixing-avernus-part-3g-xandering-the-dead-three

These aren’t “Melan diagrams”, they’re graphs (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graph_theory). Specifically, graphs that only have nodes with at least 3 edges – nodes with 1 or 2 edges are ignored. If you are going to analyse them, calling them by their right name let’s you find 300 years worth of analysis done by other people.

@Dale, what important insight does 300 years of graph theory bring to dungeon design?

@croald many including the original one – that you can’t cross 7 bridges to an island once without crossing at least one more than once.

I mean, we’re talking about dungeon design here. I suppose you could have a dungeon where you needed to cross seven bridges exactly once each, but I suspect it would not be playable. 🤷♂️

@croald: You can generalize the observation, though. Certain topologies will allow PCs to traverse a dungeon without doubling back or crossing their own path; other topographies will REQUIRE it.

I’d ask whether the alternate entrance at Area 28e would add a nontrivial loop, but it looks like that isn’t in the 5e map at all and was possibly just a misprint in the 3e map. In the 5e version, the masonry wall is clearly solid. (Then again, the 5e map is kind of wall-crazy in general. In the 5e map it appears that the masonry wall on the west of the Citadel extends 90+ feet thick, off the edge of the map. That’s…really really weird, and was very much not the case in the 3e version.)

As somebody who has studied some graph theory, I have to agree with croald here. Yes, Melan diagrams are graphs, but there’s really no need to start using maths terminology, which will alienate more than it will help. There is not really all that much from graph theory that will help in dungeon design. Who cares if your dungeon is 4-colourable, or if it’s planar or what its minimum spanning tree looks like? (Also, I’m not going to go into here how badly the Königsberg bridge problem has been mangled by you guys to the point, just that this is not how it goes and what its point is.)

Graph theory, like lots of maths, spends a lot of time proving things we already consider true from common sense, and then again spends most of the time of that on those edge cases which never come up in reality. Like say the concept of the minimum weight cut: Long laborious maths definition and algorithm to find it, to in the end be the same as you’d point out if people asked you to find a bottleneck.

Much more importantly than graph theory is to me mentioning the word topology (that’s actually what you mean, Justin, not topography), which is the wider field of mathematics concerning itself with how things differ based on how they are connected. Distances and directions are unimportant for topology, only the neighbourhood relationship matters (which, again, is completely intuitive for this purpose, but needs to be lengthily defined for actual maths). That’s why we straighten out paths in the Melan diagram, because we don’t care about the turns. What matters is that the Crypt can be found by going through the Great Hall, and that’s what we put down on paper.

I’ve gotten a lot of mileage out of these not for analyzing dungeons but for analyzing mysteries, in particular where to flesh them out to give the players more angles to attack from. It pairs will with your “rule of three” for clues, since it highlights places where certain clues can only be found one way, or there is no alternative route to reach the conclusion the players are meant to draw. It’s not a perfect system, you can’t map every leap in logic the players will make, but it has the same effect of demonstrating linearity that would otherwise be obfuscated by the writing

Yes! I’ve always wondered how those maps work. Especially the “transitioning to next level” symbol. I had no idea what that was. Thanks for breaking it down.

Sorry, I find this utterly meaningless.

It does not matter to me how many “you can go left or right” there are in a dungeon. It’s “lone wolf” design, and utterly meaningless, because there is no real choice at all there.

The point is what is in the room.

@Perkele: It’s hard to think outside the box (or, in your case, the room), but it’s incredibly rewarding once you do.

I sincerely hope you realize that some day.