The PCs are plane shifting into Elturel blind: They know the city has been sent to Hell, but they have no way of really knowing what the situation on the ground is (so to speak).

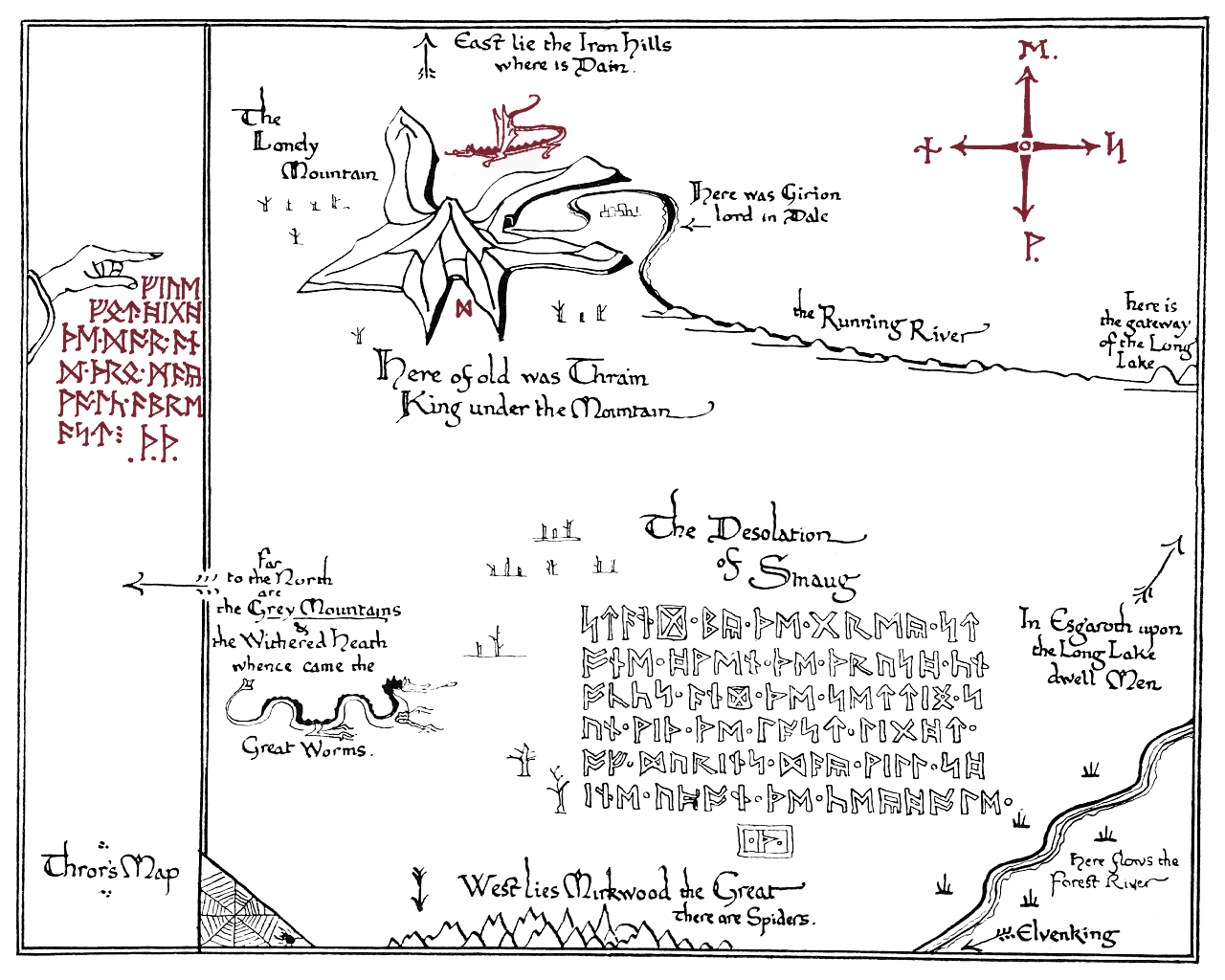

Let’s talk about the use of maps in RPGs. Actually, that’s too broad a topic. Let’s talk about the use of city maps in RPGs. Broadly speaking, there are two scenarios: First, you have diegetic maps. Like the map of pre-Fall Elturel that I mentioned the PCs might want to grab in Part 4C, diegetic maps are those actually possessed by the characters. They can be:

- Not represented in the real world. (The map is something your character possesses and references, presumably to some effect, but you, as the player, cannot see it.)

- Given as a prop in the real world which attempts to accurately represent exactly what the map would look like to your character.

- Given as a prop in the real world which is analogous to what your character would see, but not the same thing they’re actually looking at.

In practice, this is more of a spectrum than distinct categories. For example, even Thror’s Map from The Hobbit ultimately makes concessions to the reader by being an English “translation” of the diegetic map:

Second, there are non-diegetic maps. These are maps which the players can see, but not their characters. For example, when I was running Dragon Heist I put a huge map of Waterdeep up on the wall. This didn’t represent a map that the characters were carrying around with them; it was a reference that existed purely in the physical game space (along with a Harptos calendar and a map of Faerûn).

Non-diegetic maps may represent character knowledge (i.e., the map they have in their head). But they can also simply be a concession for easy reference. In much the same manner that handing the players a picture of an NPC can be the quickest way to distinguish them (even though their characters don’t have a pocket portrait of them in hand), so, too, have I found that the most efficient way to conjure up a cross-town trek in the minds of the players is to simply point the laser pointer at the poster map on the wall and trace the route with brief descriptions.

Which, finally, brings us to the poster map of Hellturel included in Descent Into Avernus. When should you give this map to the players?

ARRIVING IN ELTUREL

First, a brief digression. By and large, we are not going to be changing the initial beats of what happens in Elturel:

- The PCs arrive.

- They get a first impression of the city.

- The person who brought them to Avernus (probably Traxigor) panics and abandons them.

- A woman with two toddlers comes running around the corner, pursued by a couple of bearded devils.

But we are going to finesse them a bit.

Let’s start with this chunk of boxed text from the book:

When looking at a BIG MOMENT like this, it can be tempting as a GM to just pile the whole thing up on the players. That can work, but I’ve found that it’s often more effective to break the BIG MOMENT into its distinct parts — each major detail, each revelation, each meaningful moment — and then space them out (even if only a little).

This is partly about pacing, but it’s also about slowly building up a mental image for the players over time. By layering in additional details sequentially over time, in my experience, it’s easier for the players to really immerse into the environment. You get more buy-in.

I’ve been doing this long enough that I kind of do this instinctively. But in breaking down the arrival in Elturel, I identified these moments:

- Arriving in the street. Hot air. Crumbling buildings. The sky of Hell and the transformed Companion above you.

- Traxigor is nervous.

- Spotting the High Hall on a distant bluff.

- Huge clouds of smoke to the east; the city is on fire.

- DEVILS!

- Traxigor panics and flees.

- The first earthquake.

- WE ARE FLOATING IN THE GODDAMN AIR!

(That last beat probably happens much later. We’ll come back to it.)

Note that there’s nothing sacred about this sequence. For example, you could easily rearrange and remix the middle beats:

- Spotting the High Hall on a distant bluff.

- DISTANT EXPLOSION! to the east. There’s huge clouds of smoke. The city is on fire. Traxigor panics and flees.

- DEVILS!

And in actual play the players could easily shift these things around. For example, if they immediately look up into the sky and try to get their bearings you can immediately mention them seeing the High Hall and the huge clouds of smoke to the east before mentioning Traxigor getting nervous or triggering the distant explosion. The basic idea, in fact, is to give the players at least a couple of beats to react to what’s happening.

This might be even clearer if we look at the next block of boxed text (which actually happens in the middle of this sequence):

Although all glommed up as one moment here, imagine it lightly restructured as:

- You hear a scream from around the corner.

- [Players have a chance to quickly declare one thing they do in response.]

- A woman with two toddlers runs around the corner.

- [Players have another chance to quickly declare their response to this. Maybe the woman can shout out something to them in response.]

- Devils come around the corner.

- [Ask the players to roll for initiative.]

- Traxigor panics and flees.

I think you can see how this draws the players into the scene: By the time the devils actually show up, they’re already involved and invested in the actions that are playing out.

Here’s the key thing: When the PCs arrive in Elturel they are confused, disoriented, and need to get their bearings. Traxigor abandoning them should escalate that feeling, isolating and trapping them. They should feel simultaneously claustrophobic and overwhelmed by the vast unknown which surrounds them.

The take-away here is that simply whipping out the Hellturel map as soon as they arrive would cause most or all of these distinct moments to collapse into each other, simultaneously undercutting the emotional tension of the situation.

GETTING THEIR BEARINGS

So when should they get the Hellturel map?

First, this is obviously a non-diegetic map. (Nobody is doing cartographical surveys in the middle of the apocalypse.) Second, we’ve framed the PCs into a situation where they’re effectively lost and need to get their bearings. So the real question is: What is the meaning of the map? And the meaning of the map is that the PCs have gotten their bearings.

So when the PCs have gotten their bearings, you should give the players the map.

How can they do that? Well, I can think of a few options (and your players might come up with something else):

- They could seek out a tall building and climb to its top, allowing them to look out over the city.

- They could use magic to similar effect (a clairvoyance spell, for example).

- They could question NPCs in Elturel. (The initial woman they run into is clueless about the wider state of the city, but others might be well-informed enough to give them a briefing on the current situation.)

- They could use their diegetic map of Elturel (if they have one) to attempt to figure out where they are in the city.

What constitutes enough knowledge for them to be considered to have gotten their bearings? Well, it probably depends on their approach. On the one hand, we want to look at the type of information the map is giving them: Have they gotten that information in-character? On the other hand, while the map does contain information on every single block in the city, it’s overkill to withhold the map until they’ve somehow gained that block-by-block knowledge.

What I would do is look at the key revelation: Remember how “WE ARE FLOATING IN THE GODDAMNED AIR!” was the final moment we identified above? Well, the map is going to reveal that. So we want to make sure that the characters have experienced that moment before revealing the map. (And that could happen by them climbing a building and seeing out over the edge of the city, being told the situation by an NPC, etc.) That moment might be simultaneous with them getting their bearings, or it might happen before they get their bearings (so they don’t get the map until later) depending on how it plays out.