Using smart prep to improve your game isn’t just about the big, flashy stuff. In fact, the big, flashy stuff is often the easiest stuff to improvise while running the game. It’s actually the small, subtle stuff that requires thought and precision to implement effectively but also adds great depth to the players’ experience that can benefit the most from the care and consideration of smart prep.

One example of this is what I refer to as the exposition drip: When you have a significant bit of lore that you want the PCs to learn, but rather than delivering it all at once, you break it up and deliver it in chunks over time. This is can happen over the course of a single scenario, but you can also pace it out over the course of an entire campaign.

There are a few reasons for doing this:

- It allows you to pace the revelation to match the procedural plot. (This is particularly useful for mysteries, where the players consistently feel as if they’re making progress as they collect the puzzle pieces that add up to the ultimate conclusion.)

- By breaking the information up into smaller pieces, delivering them over time, and, thus, consistently revisiting the same bit of lore (without it becoming repetitive), you make it more likely that the players will learn and retain the lore.

- When you want a particular moment to pack a punch (“You have just discovered the lost sword Excalibur!”) it’s best if the players already understand the significance of what’s happening (what Excalibur is, who King Arthur was, etc.) before the punch is thrown. Preferably long before.

- On a similar note, breaking the lore into multiple parts allows it to be given to the players through multiple delivery mechanisms. This can make it substantially easier to make the players actually care about the information. (See Getting the Players to Care for a much longer discussion of this.)

And the reason this benefits from prep is because figuring out how to structure the exposition and the pace at which it should drip out benefits from pre-analysis and specific planning: If you mis-structure the exposition breaks, then the players can get ahead of the drip. If you pace the drip wrong, the players can lose interest or focus on the topic.

CREATING THE EXPOSITION DRIP

The process for creating an exposition drip is fairly straightforward.

First, identify the information they need.

Second, break that information into discrete pieces, each of which can be defined as a single revelation.

Third, determine how the PCs will learn each revelation. Ideally, set things up so that they can gain the information actively instead of passively (show instead of tell).

The way in which you actually do this is ultimately more art than science, though. For any given exposition drip, it’s a complex alchemy of the information being conveyed and the circumstances of the scenario or campaign in general.

NO, I AM YOUR FATHER

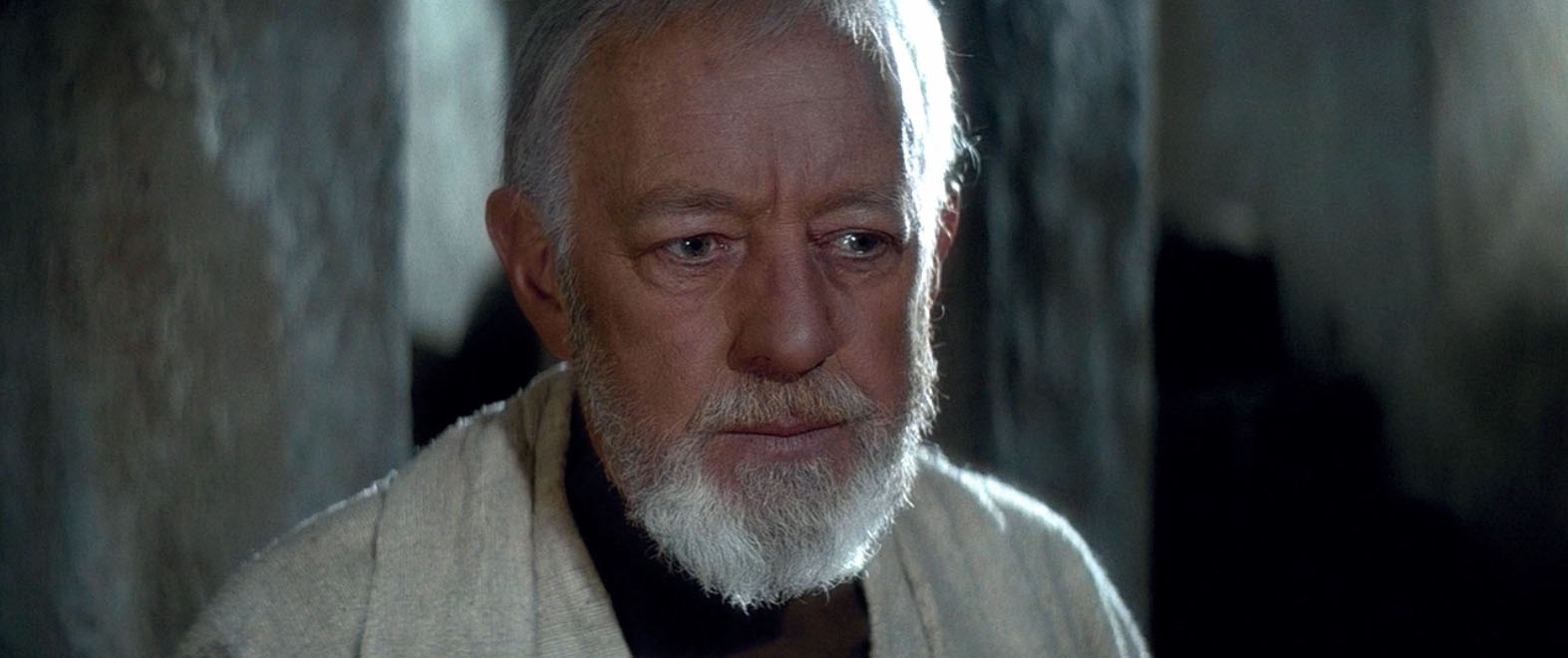

He’s a faux-media example of an exposition drip. You want one of the PCs to discover that their father is actually Darth Vader. This becomes a sequence of revelations, delivered as an exposition drip:

- Darth Vader is the Emperor’s right hand. He’s a really bad guy.

- Luke’s father, Anakin Skywalker, served with Ben Kenobi and was a hero during the Clone Wars.

- Anakin Skywalker was turned to the dark side of the Force and became Darth Vader.

- There’s still good in Darth Vader. It’s possible that he could be turned back to the light side of the Force.

Let’s consider, for a moment, the alternative to doing an exposition drip for this information. Luke follows R2-D2 to Ben Kenobi in the deserts of Tatooine.

Luke: You fought with my father in the Clone Wars?

Kenobi: You may have heard of Darth Vader. No? He’s a powerful Sith lord who serves the Emperor, and he’s also your father. He was my apprentice during the Clone Wars and I failed him: The Emperor, who is also a powerful Sith lord, turned him to the Dark Side. He betrayed and murdered the Jedi. But I think there’s still good in him, and it’s possible he could be turned back to the light side of the Force.

Hopefully it doesn’t require too much explanation to understand why this is not the most effective way of presenting this information.

Perhaps the most obvious one is that “Darth Vader is your dad” doesn’t really pack the same emotional punch when you just found out who Darth Vader was a couple sentences earlier.

But also note how this puts the procedural conclusion of the story — in which Luke tries to redeem his father — front and center from the first session of the campaign. This means that the campaign is either going to be very short, or it means that you’re going to keep hitting the “Luke confronts his father and tries to turn him to the light side” story beat over and over and over again until it becomes repetitive and boring.

THE THREE CLUE RULE

You may have noticed that I’ve been using the term “revelation” for each individual chunk of the exposition. This is a term I also use in the Three Clue Rule, and that’s not a coincidence. Each drip of exposition is a conclusion that you want the PCs to make and, therefore, the Three Clue Rule applies:

For any conclusion that you want the PCs to make, include at least three clues.

Take, for example, the conclusion that Darth Vader is a really bad guy. Lay out the clues:

- He attacks Leia’s ship at the beginning of the scenario and kidnaps her.

- Ben Kenobi tells Luke that Darth Vader murdered his father.

- Darth Vader kills Ben Kenobi.

- Darth Vader freezes Han Solo in carbonite.

(You might note that some of the other drip revelations mentioned above don’t have three separate clues appear in the films: That’s because they’re films, not an RPG scenario. Or, if we want to live inside our analogy, the films are a specific actual play and the PCs missed some of the clues. That’s why you follow the Three Clue Rule in the first place, right?)

Also keep in mind the corollaries of the Three Clue Rule, like using permissive clue-finding to opportunistically seize opportunities to establish revelations when PCs take unexpected actions.

DRIP DEVELOPMENT

As with mystery scenarios, one of the great things about implementing the Three Clue Rule is that it usually forces you to creatively engage with the material to a depth where the material sort of takes on a life of its own.

For example, as we begin designing this Darth Vader exposition drip we immediately run up against a conundrum: Why doesn’t Obi-Wan just tell Luke all of this stuff?

“He must be scared to tell him,” our hypothetical GM muses. “Obi-Wan lost Anakin. He was seduced by the dark side of the Force. Obi-Wan must worry that if Luke knew the truth about his father, then he would also be seduced. If Luke knew the truth, that strong emotional connection would become a conduit for his own corruption. So he lies. But he can’t conceal the truth entirely… he tells the truth from a certain point of view. The good man who was Anakin Skywalker was destroyed when he was consumed by the dark side; he was transformed into something else.”

In this process, our hypothetical GM has suddenly made the Force — which he’d previously just conceived of as kind of like good energy vs. demonic energy — into a more richly textured metaphysic. There’s now a whole concept of emotional relationships, and Darth Vader’s own struggle with identity has also emerged from this thought process.

You’ll find this sort of thing happening all the time when you design exposition drips: Either figuring out why the information is fractured in the first place will create interesting consequences; or the need to create a multitude of clues will create all kinds of texture you didn’t have previously; or in placing those clues you’ll find that you’ve created connections and reincorporated aspects of the game world in unanticipated ways.

INTERCONNECTED DRIPS

Wait… does Luke even know about the Force yet?

You’ll often find that certain revelations in an exposition drip also need a greater context to be meaningful. This can easily result in your needing to create another exposition drip, particularly if that greater context has significance elsewhere in the campaign. (As, for example, the Force does.)

We can also see that some of the revelations in the Force exposition drip need to be established before revelations on the Darth Vader drip, but not all of them. As a result, the two drips can be interwoven with each other throughout the campaign, with the PCs learning information about one drip and then the other. In fact, not only are these drips interwoven, but they frequently overlap — some revelations are shared between the exposition drips; or the same node of information can serve double duty by providing separate pieces of information to each drip.

The question of how many exposition drips you can have running simultaneously — how many balls you can keep in the air — is determined by the amount of complexity you and your players are capable of handling (and also, of course, what’s appropriate for the current scenario). But by having multiple exposition drips that connect to each other in different ways, you’ll usually end up with a totality that’s greater than the sum of its parts.

NON-LINEAR DRIPS

It’s easy to think about exposition drips in a linear fashion: The PCs learn A, then they learn B, then they learn C, and so forth. But as you look at each revelation in your exposition drip and consider the context necessary for that drip to exist, you’ll usually discover that this context does not, in fact, include many or any of the other revelations in the drip.

For example, you need to know that Anakin Skywalker was a hero during the Clone Wars before you discover that he was seduced by the dark side. (You need to know he was a hero before you can reveal that he’s a corrupted hero.)

But do you need to establish that Darth Vader is the Emperor’s right hand before establishing that Anakin Skywalker was a hero during the Clone Wars? Do you need to know that Anakin Skywalker is Darth Vader before discovering that there’s still good in Darth Vader?

Probably not.

So you’ll often discover that you DON’T need to worry about sequencing information: You can seed clues for a bunch of different revelations without worry about the specific order in which those clues are discovered. This is great news because (a) it makes it a lot easier to seed a node-based scenario with an exposition drip and (b) it really opens the door to discovering the unexpected during actual play.

(Take a moment to imagine what happens if Luke discovers that there’s still good in Darth Vader before he learns that Darth Vader is his father?)

NON-NARRATIVE DRIPS

As a final note here, the exposition drip technique isn’t necessarily limited to diegetic information in the game world. You can use a similar technique for mechanical concepts.

In the Eternal Lies campaign for Trail of Cthulhu, for example, the penultimate scenario features the PCs likely needing to lug explosives on a lengthy wilderness expedition. There are some mechanics involved with this which can lead to dramatic complications, but the first time I ran the campaign it was distracting trying to both come to grips with these mechanics and use them to good effect at a big, climactic moment.

So the second time I ran Eternal Lies, I found ways to incorporate these mechanics into the earlier scenarios in the campaign. As a result, by the time the PCs reached the final scenario, they were already familiar with thinking about explosives in terms of “charges” and figuring out how to deal with them on long expeditions.

This sort of thing is more esoteric than narrative exposition drips, but when you’re planning out a campaign take a look at the big, climactic moments and think about what novel mechanics are going to factor into those moments. Then track backwards and figure out how you can introduce those mechanics earlier in the campaign.

For example, if the big finale of this space opera campaign you’re planning has Luke and his father using the Dark/Light personality mechanics to try to sway each other’s metaphysical allegiance, try to figure out some moments earlier in the campaign where Luke can be tempted by the dark side so that both you and Luke’s player can become familiar with how those mechanics work. Maybe Yoda could send him to a dark side cyst on Dagobah? The Test of the Cave?

Yeah, that works.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot in regards to starting a new campaign and all the information that goes along with it. Gods, Kingdoms, factions, history characters would know, major NPCS. Potentially a ton of info to dump at the start of the game so I’d like to drip it out a bit a time. Your post is nice food for thought.

I know you have mentioned being interested in Invisible Sun, and I feel these techniques would work wonderfully with the plethora of Secrets within the game.

Little secrets lead into bigger secrets, but often the pacing and order is relevant – this article really helps think about that structure.

@Justin: It appears that there’s a missing link between part 4 of smart prep and this one

@Kaique: Thanks! Fixed!