“Most of the campaigns I’ve really enjoyed have been in systems I didn’t like.”

“A great GM can take any RPG and run a good game.”

“I just want a system that gets out of the way when I’m playing.”

What I think these players are discovering is that most RPG systems don’t actually carry a lot of weight, and are largely indistinguishable from each other in terms of the type of weight they carry.

In theory, as we’ve discussed, there’s really nothing an RPG system can do for you that you can’t do without it. There’s no reason that we can’t all sit around a table, talk about what our characters do, and, without any mechanics at all, produce the sort of improvised radio drama which any RPG basically boils down to.

The function of any RPG, therefore, is to provide mechanical structures that will support and enhance specific types of play. (Support takes the form of neutral resolution, efficiency, replicability, consistency, etc.) If you look at the earliest RPGs this can be really clear, because those games were more modular. Since the early ’80s, however, RPGs pretty much all feature some form of universal resolution mechanic, which gives the illusion that all activities are mechanically supported. But in reality, that “support” only provides the most basic function of neutral resolution, while leaving all the meaningful heavy lifting to the GM and the players.

To understand what I mean by that, consider a game which says: “Here are a half dozen fighting-related skills (Melee Weapons, Brawling, Shooting, Dodging, Parrying, Armor Use) and here are some rules for making skill checks.”

If you got into a fight in that game, how would you resolve it?

We’ve all been conditioned to expect a combat system in our RPGs. But what if your RPG didn’t have a combat system? It would be up to the GM and the players to figure out how to use those skills to resolve the fight. They’d be left with the heavy lifting.

And when it comes to the vast majority of RPGs, that’s largely what you have: Skill resolution and a combat system. (Science fiction games tend to pick up a couple of additional systems for hacking, starship combat, and the like. Horror games often have some form of Sanity/Terror mechanic derived from Call of Cthulhu.)

So when it comes to anything other than combat — heists, mercantile trading, exploration, investigation, con artistry, etc. — most RPGs leave you to do the heavy lifting again: Here are some skills. Figure it out.

Furthermore, from a utilitarian point of view, these resolution+combat systems are all largely interchangeable in terms of the gameplay they’re supporting. They’re all carrying the same weight, and they’re leaving the same things (everything else) on your shoulders. Which is not to say that there aren’t meaningful differences, it’s just that they’re the equivalent of changing the decor in your house, not rearranging the floorplan: What dice do you like using? What skill list do you prefer for a particular type of game? How much detail do you like in your skill resolution and/or combat? And so forth.

SYSTEM MATTERS

What I’m saying is that system matters. But when it comes to mainstream RPGs, this truth is obfuscated because their systems all matter in exactly the same way. And this is problematic because it has created a blindspot; and that blindspot is resulting in bad game design. It’s making RPGs less accessible to new players and more difficult for existing players.

I’ve asked you to ponder the hypothetical scenario of taking your favorite RPG and removing the combat system from it. Now let’s consider the example of a structure which actually HAS been ripped out of game… although you may not have noticed that it happened.

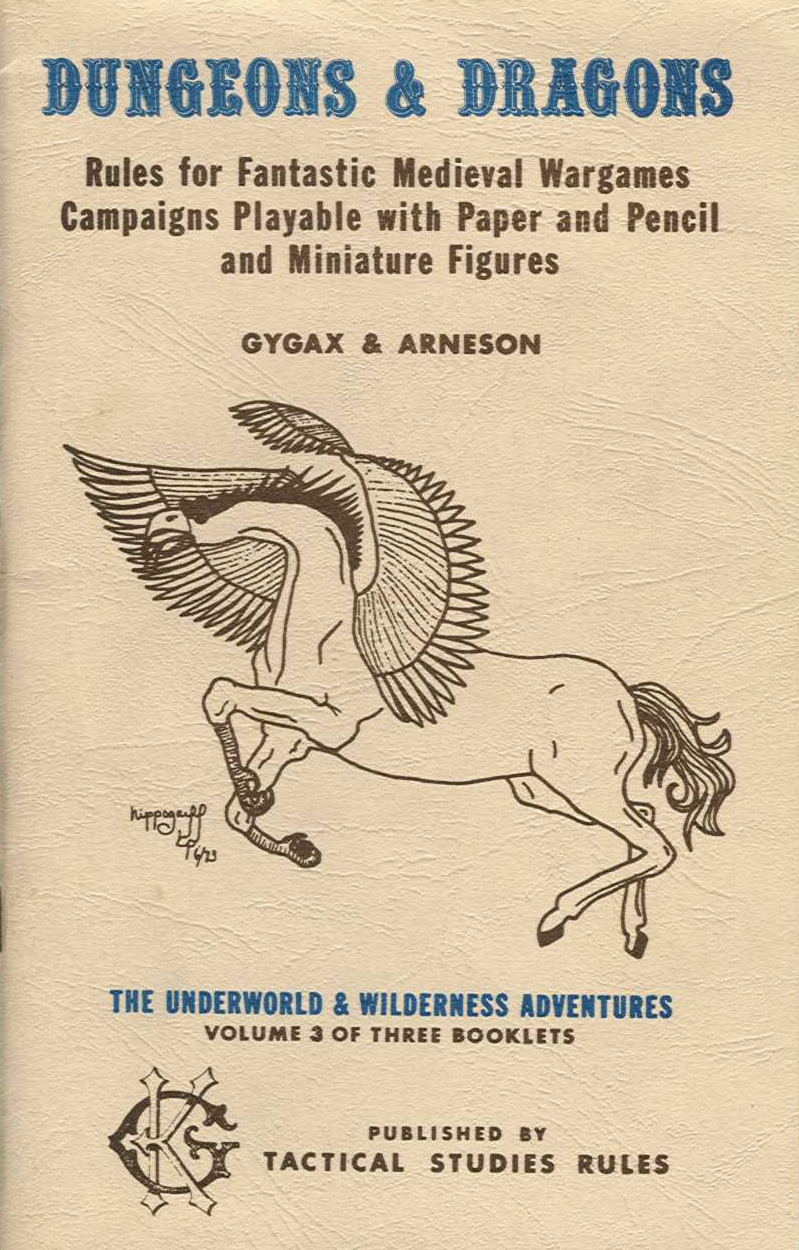

From page 8 to page 12 of The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures, Arneson & Gygax spelled out a very specific procedure for running dungeons in the original edition of Dungeons & Dragons. It boils down to:

1. You can move a distance based on your speed and encumbrance per turn.

1. You can move a distance based on your speed and encumbrance per turn.

2. Non-movement activities also take up a turn or some fraction of a turn. For example:

- ESPing takes 1/4 turn.

- Searching a 10′ section of wall takes 1 turn. (Secret passages found 2 in 6 by men, dwarves, or hobbits; 4 in 6 by elves.

3. 1 turn in 6 must be spent resting. If a flight/pursuit has taken place, you must rest for 2 turns.

4. Wandering Monsters: 1 in 6 chance each turn. (Tables provided.)

5. Monsters: When encountered, roll 2d6 to determine reaction (2-5 negative, 6-8 uncertain, 9-12 positive).

- Sighted: 2d4 x 10 feet.

- Surprise: 2 in 6 chance. 25% chance that character drops a held item. Sighted at 1d3 x 10 feet instead.

- Avoiding: If lead of 90 feet established, monster will stop pursuing. If PCs turn a corner, 2 in 6 chance they keep pursuing. If PCs go through secret door, 1 in 6 chance they keep pursuing. Burning oil deters many monsters from pursuing. Dropping edible items has a chance of distracting intelligent (10%), semi-intelligent (50%), or non-intelligent (90%) monsters so they stop pursuing. Dropping treasure also has a chance of distracting intelligent pursuers (90%), semi-intelligent (50%), or non-intelligent (10%) monsters.

6. Other activities:

- Doors must be forced open (2 in 6 chance; 1 in 6 for lighter characters). Up to three characters can force a door simultaneously, but forcing a door means you can’t immediately react to what’s on the other side. Doors automatically shut. You can wedge doors open with spikes, but there’s a 2 in 6 chance the wedge will slip while you’re gone.

- Traps are sprung 2 in 6.

- Listening at doors gives you a 1 in 6 (humans) or 2 in 6 (elves, dwarves, hobbits) of detecting sound. Undead do not make sound.

I’ve said this before, but if you’ve never actually run a classic megadungeon using this procedure — and I mean strictly observing this procedure — then I strongly encourage you to do so for a couple of sessions. I’m not saying you’ll necessarily love it (everyone has different tastes), but it’s a mind-opening experience that will teach you a lot about the importance of game structures and why system matters.

The other interesting thing here is that Arneson & Gygax pair this very specific procedure with very specific guidance on exactly what the DM is supposed to prep when creating a dungeon on pages 3 thru 8 of the same pamphlet. (These two things are conjoined: They can tell you exactly what to prep because they’re also telling you exactly how to use it.) Take these two things plus a combat system for dealing with hostile monster and, if you’re a first time GM, you can follow these instructions and run a successful game. It’s a simple, step-by-step guide.

“Now wait a minute,” you might be saying. “You said this procedure had been ripped out of D&D. What are you talking about? There’s still dungeon crawling in D&D!”

… but is there?

THE SLOW LOSS OF STRUCTURE

Many of the rules I describe above have passed down from one edition to the next and can still be found, in one form or another, in the game as it exists today. But if you actually sit down and look at the progression of Dungeon Master’s Guides, you’ll discover that starting with 2nd Edition the actual procedure began to wither away and eventually vanished entirely with 4th Edition.

The guidance on how to prep a dungeon has proven to have a little more endurance, but it, too, has atrophied. The 5th Edition core rulebooks, for just one example, don’t actually tell you how to key a dungeon map. (And although they have several example maps, none of them actually feature a key.)

One of the nifty things about a strong, robust scenario structure like dungeon crawling is that with a fairly mild amount of fiddling you can move it from one system to another. This is partly because most RPGs are built on the model of D&D, but it’s also because scenario structures in RPGs tend to be closely rooted to the fictional state of the game world.

This is, in fact, why you probably didn’t notice that 5th Edition D&D doesn’t actually have dungeon crawling in it any more: You’re familiar with the structure of dungeon crawling, and you unconsciously transferred it to the new edition the same way that you’ve most likely transferred it to other games lacking a dungeon crawling structure in the past. In fact, I’m willing to guess that removing dungeon crawling from 5th Edition was not, in fact, a conscious decision on the part of the designers: They learned how to run a dungeoncrawl decades ago and, like you, have been unconsciously transferring that structure from one game to another ever since.

Where this becomes a problem, however, are all the new players who don’t know how to run a dungeoncrawl.

Most people enter the hobby through D&D. And D&D used to reliably teach every new DM two very important procedures:

1. How to run a dungeon crawl

2. How to run combat

And using just those two procedures (easily genericizing the dungeon crawling procedure to handle any form of location-crawl), a GM can get a lot of mileage. In fact, I would argue that most of the RPG industry is built on just these two structures, and that most GMs really only know how to use these two structures plus railroading.

So what happens when D&D stops teaching new DMs how to run a dungeoncrawl?

It means that GMs are now reliant entirely on railroading and combat.

And that’s not good for the hobby.

THE BLINDSPOT

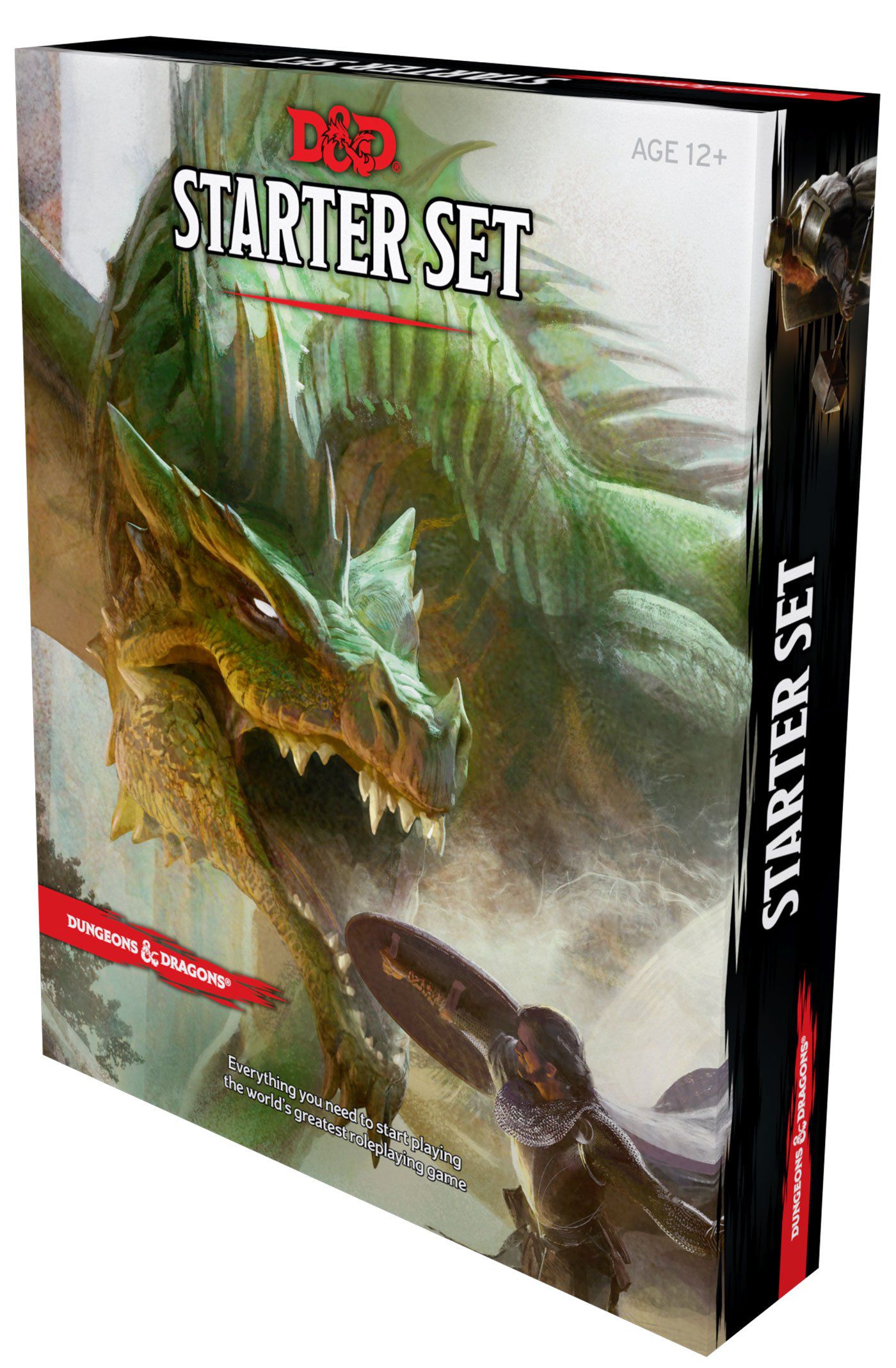

If you need another example of what this looks like in practice, check out The Lost Mine of Phandelver, the scenario that comes with the D&D 5th Edition Starter Set. It’s a fascinating look at how this really is a blindspot for the 5th Edition designers, because The Lost Mine of Phandelver includes a lot of GM advice.  They tell you that the GM needs to:

They tell you that the GM needs to:

- Referee

- Narrate

- Play the monsters

They give lots of solid, basic advice like:

- When in doubt, make it up

- It’s not a competition

- It’s a shared story

- Be consistent

- Make sure everyone is involved

- Be fair

- Pay attention

There’s a detailed guide on how to make rulings. They tell you how to set up an adventure hook.

Then the adventure starts and they tell you:

- This is boxed text, you should read it.

- Here is a list of specific things you should do; including getting a marching order so that you know where they’re positioned when the goblins ambush them.

- When the goblins ambush them, they give the DM a step-by-step guide for how combat should start and what they should be doing while running the combat.

- They lay out several specific ways that the PCs can track the goblins back to their lair, and walk the DM through resolving each of them.

And then you get to the goblins’ lair and… nothing.

I mean, they do an absolutely fantastic job presenting the dungeon:

- General Features

- What the Goblins Know (always love this)

- Keyed map

- And, of course, the key entries themselves describing each room

But the step-by-step instructions for how you’re actually supposed to use this material? It simply… stops. The designers clearly expect, almost certainly without actually consciously thinking about it, that how you run a dungeon is so obvious that even people who need to be explicitly told that they should read the boxed text out loud don’t need to be told how to run a dungeon.

And because they believe it’s obvious, they don’t include it in the game. And because they don’t include it in the game, new DMs don’t learn it. And, as a result, it stops being obvious.

(To be perfectly clear here: I’m not saying that you need the exact structure for dungeon crawling found in OD&D. That would be silly. But the core, fundamental structure of a location-crawl is not only an essential component for D&D; it’s really fundamental to virtually ALL roleplaying games.)

THE BLINDSPOT PARADOX

Paradoxically, this blindspot not only strips structure from RPGs by removing those structures; it also strips structure from RPGs by blindly forcing structures.

It is very common for a table of RPG players to have a sort of preconceived concept of what functions an RPG is supposed to be fulfilling, and when they encounter a new system they frequently just default back to the sort of “meta-RPG” they never really stop playing. This is encouraged by the fact that the RPG hobby is permeated by the same meme that rules are disposable, with statements like:

- “You should just fudge the results!”

- “Ignore the rules if you need to!”

A widespread culture of kitbashing, of course, is not inherently problematic. It’s a rich and important tradition in the RPG hobby. But it does get a little weird when people start radically houseruling a system before they’ve even played it… often to make it look just like every other RPG they’ve played. (For example, I had a discussion with a guy who said he didn’t enjoy playing Numenera: Before play he’d decided he didn’t like the point spend mechanic for resolving skill checks; didn’t like XP spends for effect; and didn’t like GM intrusions so he didn’t use any of those mechanics. He also radically revamped how the central Effort mechanic works in the game. Nothing inherently wrong with doing any of that, but he never actually played Numenera.)

As a game designer, I actually find it incredibly difficult to get meaningful playtest feedback from RPG players because, by and large, none of them are actually playing the game.

And these memes get even weirder when you encounter them in game designers themselves: People who are ostensibly designing robust rules for other people to use, but in whom the response to “just fudge around it” has become so ingrained that they do it while playtesting their own games instead of recognizing mechanical failures and structural shortcomings and figuring out how to fix them.

EXCEPTIONS TO THE BLINDSPOT

To circle all the way back around here: System Matters. But due to the longstanding blindspot when it comes to game structures and scenario structures in RPGs, we’ve stunted the growth of RPGs. Most of our RPGs are basically the same game, and they shouldn’t be. The RPG medium should be as rich and varied in the games it supports as, for example, the board game industry is. Instead, we have the equivalent of an industry where every board game plays just like Settlers of Catan.

Now there are exceptions to this blindspot when it comes to scenario structures. Partly influenced by storytelling games (which often feature very rigid scenario structures), we’ve been seeing an increasing number of RPGs beginning to incorporate at least partial scenario structures.

Blades in the Dark, for example, has a crew system that supports developing a criminal gang over time. Ars Magica does something similar for a covenant of wizards. Reign provides a generic cap system for managing player-run organizations in competition with other organizations.

Technoir features a plot-mapping scenario structure that’s tied into character creation and noir-driven mechanics.

For Infinity I designed the Psywar system to provide support for complex social challenges (con artistry, social investigation, etc.).

You can also, of course, visit some of the game structures I’ve explored here on the Alexandrian: Party Planning, Tactical Hacking, Urbancrawls. The ongoing Scenario Structure Challenge series will continue to explore these ideas.

Do you think it could be an intentional blindspot? Steering DMs toward combat and railroading seems to be a good marketing strategy to get them to buy the next product.

Or it is something which developed on accident as group procedures for dungeon exploration (as described above) gave way toward individual procedures (like individual initiative, skills checks for searching, and so forth)?

For what its worth: I use the basics of that old school system (mostly from what I remember from AD&D 1e/2e to help run Dungeon Crawl Classics RPG.

I guess I don’t follow you. How do a lot of discreet (and frankly difficult to remember) procedures teach about the importance of game structures.

I use the OD&D dungeon-crawling procedures when I run the game, and I’m strict about it too. But I wonder how common that actually is. I’ve found (since I mostly tend to run open tables at my local game shop) that total neophytes with no past RP experience are able to get into the game really quickly and have an almost intuitive understanding of turn-by-turn play—because of course they do, they’ve played board games before, and it’s familiar.

It’s the experienced players (whether we’re talking about an enthusiastic newbie who only knows 5th edition, possibly only from YouTube; a veteran 3.5 number-cruncher who thinks that having started in ’04 makes him “old school”; or an actual 1e grog who knew a guy who knew Gary) who never fail to give me a funny look when I start counting turns in the dungeon and ask the party caller for a list of actions each player is taking.

They get into the swing of things too, eventually, but you can tell that for a while there they feel stifled and confused. (These are probably the same sorts of folks who, for whatever reason, come to OSR games while looking for a loose, free-form, rulings-not-rules experience, much to my eternal bafflement.)

Very nice: 100% agreed that System Matters. Thanks for writing this!

I’m going to suggest that two details in the OD&D Vol-3 dungeon crawl procedure (p. 12) are different than what you’ve presented above:

(1) Reaction rolls are not part of every or most monster encounters. The main text says, “Monsters will automatically attack and/or pursue any characters they ‘see’, with the exception of those monsters which are intelligent enough to avoid an obviously superior force.” The reaction table further down is only for those other, exceptional, “other than in pursuit situations”. This is a point I’ve written about previously. (https://deltasdnd.blogspot.com/2011/09/power-of-pictures.html)

(2) When PCs turn a corner, my book says, “the monster will only continue if a 1 or a 2 is rolled on a 6-sided die”. So that’s 2-in-6 to continue, not 2-in-6 to stop. I find that under this rule it’s actually very easy for PCs to escape from monsters, and a dungeon with lots of little kinky passages helps them out in this regard (balanced by how mad the mapper gets).

Again, great thesis as usual.

These posts on game structures have really helped me wrap my head around something I’ve been thinking about for a long time in fairly inchoate terms. I think it’s telling that the OSR, the story games movement (The Forge et al), and the renaissance in board game design have all come at the same moment. Each is addressing the problem you’ve identified with late-edition D&D and its late-80s to early-aughts contemporaries: the problem of a loss of game structures other than combat.

It’s odd to me that the OSR folks and the story games folks — and for that matter, the board game folks — aren’t more engaged with each other’s ideas. To me, it seems obvious that each camp is trying to address the same problem. Good games provide structure to the process of creating a collaborative fiction at the table. Early D&D did this by connecting a bunch of interlocking mini-game systems together (wilderness exploration, dungeon exploration, combat, domain management); story games do this by providing concrete mechanics for building a collaborative narrative; and of course board games typically do this by providing concrete steps for playing a game with an implied fictional overlay that does not affect play. Each borrows elements from the others, and there are a number of examples out there of games that mix and match elements of board games, story games, and OSR games (I’m thinking of Ironsworn, Stars Without Number, The Nightmares Underneath, Dread, My Life With Madter, and so on).

It seems to me that an obvious point of intersection of these three approaches is the random tables beloved of the OSR, which are often positioned as “oracles” in story gaming and which give off a strong whiff of board game-esque procedure. They are a great tool for creating surprising emergent gameplay, which is exactly what the last generation of games was missing: when you rely on the unconstrained imaginations of the GM and players to generate your gameplay you almost might as well just be writing a novel together, but if you have random prompts to your imagination mixed with concrete mechanics for resolution you can get something more surprising than anyone at the table would have dreamed up without these constraints in place.

Oh, and I think it’s worth linking to Ron Edwards’ essay on this topic from The Forge way back in 2004, “System Does Matter”:

http://www.indie-rpgs.com/_articles/system_does_matter.html

As always, very good essay. And Picador, thanks for your comments, it’s super interesting.

This sort of thing is why 5e’s Dungeon Master’s Guide struck me as a waste of money compared to the other two 5e core books by the time I’d finished reading it. I don’t think I could have learned how to DM from that book. There’s accumulated advice here, random tables there, threadbare flavor text this way, clearly unusable fragments of mechanics that way… and almost nothing to tie it all together. The DM-facing parts of XGtE don’t seem to be much better — and the downtime activity section in particular seems to be equally half-hearted rehashes of already half-hearted mechanics, perhaps written out of complete cluelessness as to why people might have been dissatisfied with the originals. And then there’s all I’ve heard about how 5e adventures are written… It’s like WotC has no idea how to write DM-facing content anymore, yet seem to think they should be selling DM-facing content every six months as their primary business strategy. I’m left to wonder how exactly 5e is as successful as it is.

Of course, some of that success might be just the degree of effort they’ve put into Adventurer’s League… but therein lies another problem. It seems to be very hard to get across to some people that what I’d theoretically like out of a D&D game is NOT like Adventurer’s League… and that trying to find people to play story-heavy, player-agency-medium stuff with by putting up with months of drop-in generic railroads would be like trying to evaluate people’s suitability for a pool league by their pinball performance. …I lose people with that specific metaphor, in fact.

The blind spot you describe is also why I’ve been thoroughly stymied in my attempts to ask people how to give the parts of an investigative scenario that AREN’T clue-finding enough structure to help my players understand what, on a basic level, they should be doing with clues once they have them. Because apparently discussing what the clues might mean with the other PCs, comparing them with other clues, coming up with theories to falsify, finding ways to get more information about the clues they do have, or even so much as rolling knowledge skills to see if PCs might have insights about clues that their players wouldn’t think of are not obvious to most people. In short, I’d like a discussion-at-HQ/whispered-discussion-around-the-corner structure to go with the investigate-the-scene structure… and I can’t seem to get ANYONE to understand this. At worst, it just comes back to people insisting Gumshoe is the Holy Grail of investigative gaming, which in this particular case strikes me as akin to saying that the way to solve the problem of not having peanut butter is to just spread the jelly faster.

Chases in particular are something that you can’t really adjudicate with just the combat and exploration rules. (And if you can’t figure out how to adjudicate it, maybe you have to tell your players they simply can’t run away.) The rules for when the monsters stop chasing are nice and interactive.

Personally, I like the idea of rolling some movement dice during each “step” of the chase. If I recall correctly, B/X resolves chases with a single percentage roll – which works fine for deciding if you get to withdraw from combat, but kind of fails to capture the “feel” of a chase.

Camping and downtime (especially crafting) are two other areas where in most games there are no procedures, so you either skip over them, or you resort to minutely narrating every single thing – which can take a lot of time to get through, and probably has no particular payoff. Procedures would fix that, letting you play through those activities in a structured way.

I’ve written on my own blog about wanting procedures for navigating in the dark before. What I actually said was that I wanted a way to resolve it without resorting to excessively detailed narration, but reading this, I realize what I meant was that I wanted a procedure.

It’s funny, exploration via painstaking description of every single action is often held up as a hallmark of player skill and good old-school play, and I’ve seen it criticized as “pixelbitching”, but I’ve never seen it criticized for being what it also is, which is an absence of a systematic gaming procedure.

Thanks Jordan!

Anne and Pferyx: really good points. I feel like there might be an existing line of rpg theory that might give us some general terminology to discuss the problem that I think you’re both talking about, namely the lack of systematic gaming procedures in a given domain, leaving players to describe every action they take and DMs to adjudicate outcomes ad-hoc. So:

1. The system provides procedures for finding clues; putting those clues together and acting on them is assumed to be something the players and DM can describe and adjudicate without any guidance from the system.

2. The system provides procedures for combat and exploration, but downtime activities like camping and crafting are assumed to be (etc etc).

Of course “the OSR” (in quotes because I’m about to point out that it’s not necessarily a monolithic movement or philosophy) pulls in two different directions here. On the one hand, Justin is right that early editions of D&D provides lots of non-combat procedures that were gradually abandoned. On the other hand, the OSR is big on admonition like “rulings not rules” and “player skill not character skill”.

Of course what we see in practice, as Justin points out, is that games providing lots of crunch in one area (eg combat) will lead to gameplay focusing on that area. When all you have is a hammer etc. I would hope that anyone who lived through the last 25 years of RPG design would welcome games providing crunch for running social challenges, exploration, downtime, etc.

In fact in my own noodling around with RPG design I’m finding that it’s almost better (for me!) to initially approach the game as though it’s going to be a board game. In other words, design something that runs entirely on fixed mechanics, with all interactions between the fiction and the mechanics being one-way (mechanics dictate fiction but not vice-versa). This is almost the approach taken by Vincent Baker’s Apocalypse World: the mechanical systems in the game exist as a closed set of “Moves”. But of course AW is more of a story game/RPG hybrid, and the fiction can both trigger and be affected by the outcome of Moves, much like in any RPG. I find that if I force myself to try to design a self-contained, closed set of mechanics that can be played on their own without any ad-libbing to “fill in the gaps”, which is to say a board game, then I can get much closer to a compelling RPG or story game than if I try to cheat by leaving certain domains of play “free form”.

My default choice for making this sort of point via play is to sit people down for a few Torchbearer sessions. When they see a D&D-style experience filtered through Burning Wheel’s uncompromising emphasis on system, the scales begin to fall from their eyes. 😉

TIL: There used to be rules for dungeoncrawling in D&D. I wonder if having such rules in 5e would have changed my party’s experience in Tomb of Annihilation or Out of the Abyss.

@Dave T.: Torchbearer is one of those games that I see habitually mangled by people who try to run it just like every other RPG they run, so a great example coming and going.

If you want to get a similar bang for a much smaller buck, try doing in actual play something that I describe in the first installment of the Game Structures series:

Player: I want to explore the dungeon.

GM: Okay, make a Dungeoneering check.

Player: I succeed.

GM: Okay, you kill a tribe of goblins and emerge with 546 gp in loot.

@Yildo: Quite possibly!

This problem is actually quite difficult for anyone who understands the dungeoncrawling structure to see in actual practice: If you’re a GM, then you’re applying the structure yourself. But if you’re a player, you can often impress the dungeoncrawling structure onto a game even if the GM wasn’t familiar with it by virtue of the types of action declarations you make — both the scope of them and also the nature of them.

I began getting a sense for this, for example, when I was running an OD&D open table: Seeing dozens of players come through the same scenarios, I became very aware of the effect that experienced players (with the preconceptions they were bringing in) could have on how the table approached and thought about problems.

I’m really happy to see this post. I’ve always been a little confused when I’d read this blog and come across references to the “dungeon crawling” structure disappearing from D&D. Having started with 3.5 I never knew what was missing. “We go into a room, make a few checks and move on. Isn’t that a structure?” This fills some of those holes and makes me really interested in seeing a dungeon crawling focused game–as opposed to a combat focused one–in play. It’s as if I discovered I’ve been running combat all wrong and there are supposed to be initiative rules instead of letting players just sort of declare actions whenever they feel like it. The fact that I’ve only ever seen exploration scenes played that way is baffling, it seems so obvious in retrospect.

Also very minor things like “Taking 20” from 3.5 begin to click. That being an option for the players also makes more sense if you assume “structure time constraints” as opposed to “GM fiat time constraints.” Having enough time to set everything aside and take 20 is an exceptional luxury, not something you can always do unless the GM decides to take it away.

I’m not going to run those rules exactly as written, there are better ways to map secret door discovery to modern rule systems than a flat d6 roll, but I definitely want to test some of those ideas out and see how engaging the exploration portion of the dungeon crawl can be.

Maybe I overlooked this, but what is the difference between game structure and scenario structure? And why combat is not classified as scenario structure? I think, it is possible to run a game (althow probably not very interesting one) using only combat structure.

Justin uses Scenario Structure and Game Structure interchangeably, and combat is definetly a scenario structure. It’s usually the only scenario structure a rule system provides.

And I’ve personally run a only combat game once. It was XCOM as a Savage Worlds setting and consisted really only of a very short introductory scene followed by me putting the figure flats on the battle mat and telling them to start rolling dice. It was a lot of fun, although they did accidentially kill their inside man because they failed to notice one of the aliens wasn’t shooting back.

@Rob: If you’re interested in “structure time constraints”, there’s a couple of articles by the Angry GM you should check out.

The first one, where he explains the need for a mechanical system to give players a sense of urgency, and then suggests such a system, is at http://theangrygm.com/hacking-time-in-dnd/

The second, which was written just a few weeks ago, presents a revised version of the system and also talks about how it can be adapted to situations other than dungeon-crawling: http://theangrygm.com/tension-on-the-road/

I haven’t used the system myself, or seen it in use, but apparently a lot of people have found it very useful.

The more I read this blog, and especially the series about game structures, the more I would love to have (or help create) a Big Book of Scenario Structures as a counterpoint to modern RPG rulebooks.

I imagine it would feature chapters of scenario structures, starting with a short discussion of the philosophy, followed by the strict order of turns and evaluations performed, similar to how it’s done with combat. To cap it off, every structure should have a named replacement skill in case you don’t want to get into that scenario, or it doesn’t fit your genre (Don’t want a full-fleshed fighting system for your game about courtly intrigue? Okay, here’s how you resolve an entire combat as an opposed Fighting roll), plus a list of feats/talents/spells that are used to modify the rules of that scenario structure (Without a fighting scenario, there is no need to have a riposte skill, for example).

I think that last point is really important, because without a rigorous scenario structure with explicit rules, the feat selection to focus on something atrophies. For example, Savage Worlds has tons of Combat feats (about half of its entire list, I’d say). Feats related to Dungeon Crawling? … One, to better detect traps. Just looking at the above OD&D procedure, I can think of half a dozen feats that could provide bonuses: Needing less time resting, better chance of surprising monsters, making monsters more willing to talk, making monsters more likely to give up, quicker movement speed, better secret door discovery, and so on.

While sure, the result wouldn’t be able to represent any particular genre as well as a product focused on providing fitting structures, it would still be a great basis for any kind of roleplay you want.

I just read another Angry GM article today (also from a few weeks ago) that, coincidentally, makes some of the same points that Justin does about the lack of mechanical support in the DMG for certain types of game structures. Here’s the most relevant excerpt:

“Basically, when the players are wandering around the dungeon, moving from room to room and Encounter to Encounter, game is happening. But the game is sort of in this inbetween state of freeform whateverness. When the party is traveling across the wilderness, from point A to point B, and having random encounters along the way, they are stuck in an undefined state of playing, but not in any structured way. And when the party is exploring a town getting to know the locals and the lay of the land or when the party is wandering around following leads during a murder mystery, they’re in this non-state of just sort of dicking around.

Now, you may not see the problem here. And that’s fine. Because lots of GMs eventually figure out how to run the game in that state, in a more freeform way. And lots of adventure writing GMs allow for that stuff by, say, making a map of the town and a key that shows who is where and has what information. Or just making a dungeon map. Or a flow chart. Which all works perfectly well.

Except, because that state of play is this vague sort of “inbetween the game parts” state, very few people actually think to do any more with it than just let the players wander around through it until an encounter happens. Basically, the adventure becomes this featureless ocean and the players are just sailing from island to island. And all the interesting things happen on the islands. And the best mechanics anyone can come up with for the featureless ocean is to roll randomly to have another island appear. A random encounter. No one thinks of doing anything with the ocean. Because it isn’t anything but the space between encounters.”

– http://theangrygm.com/between-adventure-and-encounter/

I would argue that the dungeon crawl has partially disappeared from recent editions of D&D because… players are no longer interested in dungeon crawls.

I grew up playing super iconic things like Caves of Chaos, but have you gone back to *read* those modules lately? They are unbearably long and grindy. Lots of 10’x10′ rooms with 3 zombies in them (how does this even physically work with 5′ squares?).

Sure, reading those 1st edition rules is super cool, and an interesting blast from the past. But they’re almost closer to a board game than what players consider “modern D&D”. The focus these days is more on story and non-combat elements (RP, exploration, intrigue, investigation, puzzles, etc). These days if a session has more than 1-2 encounters in 4 hours, I usually end up exhausted as both a player or a GM.

@Wonton: That doesn’t really hold up, though. Every single adventure product published by WotC includes a dungeon. If the intention is to remove dungeons from Dungeons & Dragons, you’d think they’d stop publishing nothing but dungeons.

Fascinating post Justin!

“Justin uses Scenario Structure and Game Structure interchangeably, and combat is definetly a scenario structure.”

If so, why combat is not mention in this list?

“In my experience, the vast majority of GMs are limited to just three structures:

Railroads

Dungeoncrawls

Mysteries”

https://thealexandrian.net/wordpress/39941/roleplaying-games/scenario-structure-challenge

Of course it may be just an accidental oversight, I am not sure.

*I* wouldn’t call combat a scenario structure, and I don’t think that’s how Justin is using it either. If you compare the lists of examples he gives for each (i.e. game structures and scenario structures), I think you can see what the difference is.

Game structures include: tactical hacking, party planning, urbancrawls

Scenario structures include: railroads, dungeoncrawls, mysteries

I interpret that to mean that “game structure” refers to mechanical implementation, and “scenario structure” refers to the overarching narrative framework of the adventure. Of course, the two categories bleed into one another, because form follows function. You could certainly argue that urbancrawls and social events qualify as scenarios, but the articles he linked are about coming up with game structures to support those scenarios.

As to your question of why combat isn’t considered a scenario structure, I’d say that’s because combat isn’t a scenario in the narrative sense. You could certainly have a scenario that features lots of combat, but the combat itself *isn’t* the scenario — the *reason* for the combat is.

That is why I am confused. Dungeoncrawl structure, as presented in this text, certantly is a mechanical implementation, and I can not see any sugnificant difference between dungeoncrawl and urbancrawl in this regard.

Also, why you could not say “dungeoncrawl itself *isn’t* the scenario — the *reason* for the dungeoncrawl is”? Yes, there can be a game, where the whole scenario is just dungeoncrawl and treasure-hunting, without any external reason. But I can imagine a game, where the whole scenario is just combat (a big battle or an arena tournament) without any external reason.

So I hope, that Justin will explain the difference between game structures and scenario structures, if there is any difference.

Sorry, I’m not getting the time to properly engage with this really cool conversation. But hopefully I can clarify some stuff regarding structures: All scenario structures are game structures, but not all game structures are scenario structures.

Scenario structures tend to be less mechanically oriented (and may feature no mechanics at all; for example, the Three Clue Rule), but not necessarily so (as in the example of OD&D dungeoncrawl).

In practice, you can often take a scenario structure with specific mechanics and make it generic by taking the mechanics out (although you’ll often lose specificity). You can also do the opposite by taking a generic scenario structure and add mechanics to it in order to more specifically define it (for example, you could take the Three Clue Rule and wed it to a specific mechanical structure for finding clues… which, of course, you probably do ALL THE TIME without even thinking about it).

This is how you move structures from one RPG to another: You strip out the mechanics to make them generic, move them to a different system, and then (usually) add the mechanics back in to restore the specificity (or create new specificity appropriate for its new application).

I’ll often refer to a particular scenario structure as if it were one solitary thing when it’s really a whole bunch of closely related structures. For example, as mentioned above, OD&D’s specific dungeon crawling structure is not the only dungeon crawling structure (although any dungeon crawling structure is going to share certain core elements).

I would generally NOT consider combat a scenario structure because it’s not a structure that you build a scenario around; it’s a game structure that you use to resolve an encounter.

I would consider urbancrawl (in the sense of my series on urbancrawls) a scenario structure, along with dungeoncrawls and hexcrawls.

This rings so true with some games I see now. All they focus on is skill resolution and combat. Games that are supposed to be focused on heisting (Shadowrun anyone?) severely lack rules to help the GM figure out the structure of a heist to keep things understood and level for the players. This inevitably leads to the problem of players lacking direction, so they sometimes spend hours trying to figure out a working plan, or the GM changes up things on the fly, creating an unfair experience for players. The players and GM are the ones that have to do all the heavy lifting for a system that bills itself as a heist game. Ridiculous.

This lack of structure can leave many new players flopping, especially new GMs. Perhaps it contributes to the GM drought? Imagine if during combat, the GM decided your attacks did less damage because there werent actually any clear rules for damage! I can even point to Call of Cthulhu, a horror mystery game whose ruleset has very little in the way of a mystery structure or any special methods for using skills in an impactful way for the investigation. This post has resonated with something I have felt for a long time and only increases my love for systems with structures for non-combat options, or a structure that hones in on its advertised playstyle, like Gumshoe for mysteries or Blades in the Dark for heists.

Thank you for your answer, but I stil can not grok the difference.

Are scenario structures a type of game structures, which is used to build scenarios? Then what exactly counts as scenario? Can we say, that dungeoncrawl structure is used to resolve an encounter with a dungeon, like combat structure is used to resolve an encounter with an enemy?

Combat structure definitely can occupy a same place within adventure, as dungeoncrawl structure. For example, to become champions of the king, PCs must get the legendary sword from the ancient crypt (using dungeoncrawl structure). Or they must defeat qurrent champions of the king in a tournament (using combat structure). Why dungeoncrawl does count as scenario and combat does not?

Also, can you take a game structure (which is not scenario structure) with specific mechanics and make it generic by taking the mechanics out?

I’d sort of agree with both Angon and Justin here: There is a difference between combat and dungeon crawling, but I’d not subscribe to the strict distinction.

What I’d say is what sets them apart is more the aspect of time than a qualitative difference in their rules. Because combat turns happen faster than mystery “turns”, it’s easy to consider a single combat event not meaty enough for an entire scenario. However, not only the examples given above, but also Precious Encounters™ taking forever show that it is possible to fill a roleplay session with only combat.

I could probably write several blog posts about time, how it relates to both game structures, wizard/fighter balance as well as GM practise, but I don’t have a blog. So here’s my short version. In combat, turns are clearly defined as taking a smallish number of seconds (let’s say like 5). In the OD&D dungeon crawl structure, each turn takes a minute. In an urbancrawl, it’s probably useful to chunk time for moving into and exploring city neighbourhoods in 15-minute turns. Hexcrawling is chunked in turns of 4 hours. But if there are good, mechanically oriented game structures for all of these, I believe they will all take an about equal amount of real-life time to resolve, and are all equally valid for the “taking turns” happening over an evening between GM and players.

And if one would actually go through with the high-level play of OD&D and have fighting-men build castles and control lands, then having turns in lengths of 2 days or even 1 month wouldn’t seem to far-fetched. (Why two days? Because then you get an even exponential progression with factors around 14 between every step. Next step would be 1 year.)

Of course, the longer a turn in a scenario structure takes, the more usable it appears for session-filling and campaign purposes, because it’s possible to nest more layers of sub-structures into the scenario: The dungeon crawl happens in a certain 4-hour turn of the hexcrawl. The combat happens during one of the 1-minute turns of the dungeon crawl. But I wouldn’t call the whole thing clear-cut, and think that selecting and being aware of the right time scale for the scene is an important GM skill.

You seem determined to draw to draw a sharp line between “game structures” and “scenario structures”, which I don’t think is either possible or necessary.

“I can not see any significant difference between dungeoncrawl and urbancrawl in this regard”

Who said there was one? An urbancrawl is a scenario structure just as much as a dungeoncrawl is. It wasn’t on the list of scenario structures in the previous article which you quoted, because “the vast majority of GMs” don’t use urbancrawls.

“Also, why you could not say “dungeoncrawl itself *isn’t* the scenario — the *reason* for the dungeoncrawl is”?”

I suppose you could say that (although I’d point out that for some players, treasure-hunting is reason enough to explore a dungeon). But that would be beside the point. The issue at hand isn’t whether a dungeoncrawl is a scenario in and of itself, but the fact that the 5e DMG doesn’t provide any formalized *structure* for running a dungeoncrawl.

“But I can imagine a game, where the whole scenario is just combat (a big battle or an arena tournament) without any external reason.”

“For example, to become champions of the king… they must defeat current champions of the king in a tournament (using combat structure).”

What you just described *is* a scenario. You provided the reason why the PCs are fighting: to become champions of the king.

I suppose that by a strict dictionary definition of the word, “We are fighting orcs” is a scenario. But that’s not a very *useful* way of using the term when it comes to D&D. If all you’re doing is fighting one combat after another with no rhyme or reason, you’re not really playing D&D, you’re just playing a tactical miniatures game that uses D&D rules. Even Street Fighter provided a story to explain why the player was fighting.

“Are scenario structures a type of game structures, which is used to build scenarios?”

Yes and no. “Scenario structure” could refer to the narrative flow of the game, or the mechanical tools used to implement that narrative flow. I think that Justin has used the term in both ways — after all, he listed “railroad” as an example of a scenario structure, and you don’t need any mechanical tools to railroad your players.

“Also, can you take a game structure (which is not scenario structure) with specific mechanics and make it generic by taking the mechanics out?”

I would say no, because without the mechanics, there is no *structure*. You can have a scenario (i.e. a narrative situation) without mechanics, but if you take a (non-scenario) game structure and remove the mechanical elements, you have a game with no rules, which is a contradiction in terms.

Two weeks later, I receive an email that’s an ad for the new generic Cypher System Rulebook. Why is that relevant to this thread? Simple: because so many systems cover identical territory, the email had *the same sales pitch as every other generic system out there*. Aside from alluding to “an X Y who Zs”, it didn’t say a thing to distinguish itself — and that, I think, is telling. Really, it surprises me that the industry itself has yet to notice that generic system sales pitches are identical…

I’m not sure if I’m on track here.

A Scenario Structure is a way of conceptually organizing a collection of scenes (eg a Heist, Mystery, or the 3-clue structure), scenario (eg the ‘crawl structures), or an open-ended RP scenario. The third seems to be the way most role playing is dealt with.

While Game Structures have a mechanical system of resolution in addition to the Scenario Structure. The clearest example here would be Combat.

For me, the confusion is that I can take the urbancrawl (or hexcrawl) and run it as a Game Structure or a Scenario Structure, depending on where I use the mechanics. For example at the end of combat with the dead and wounded lying around the plays loot the corpses (or soon to be corpses). This is the point I tend to switch out of the action-resolution-narration structure of the Combat system (ie Game Structure) into a generalized action-narration structure (ie Scenario Structure).

I had a related incident with my All Us Gamers game design. A reviewer who has been in the industry as long as I have gave me feedback to strip out all the how to play stuff I put in the base game (how to start a session, how to game master, how to prep) because role players already know it.

Ungodly minor nitpick: the 2-in-6 chance after turning a corner or going up a stair and 1-in-6 chance after going through a secret door is the chance the monsters *keep* pursuing, not the chance they *stop* pursuing. (Page 12 for reference.)

Fixed! Thanks, Charles.

[…] 2. Formalne zasady podróży po powierzchni i w podziemiach. Zalicza się do nich wspominana już wyżej mechanika spotkań losowych, ale również reguły ukrywania się przed wrogami, sztywno określony czas potrzebny na przeszukiwanie komnat i wyważanie drzwi, zasady gubienia się w terenie, a nawet system pozwalający prowadzić pościgi (kto by się spodziewał! To nie Savage Worlds). Formalne, znane graczom zasady pomagają im planować wyprawę (a zwłaszcza planować moment, kiedy trzeba już zawrócić); z drugiej strony tworzą bardzo prostą w prowadzeniu strukturę gry, przyjazną dla początkujących i zapracowanych prowadzących (więcej o tym pisze Justin Alexander w świetnej NOTCE). […]

If I wanted to revisit dungeoncrawling procedures from pre-3.x days, what’s the best place took look, which edition/rulebook would get me a good basic structure?

@Ceti: Check out Old School Essentials (OSE), which I understand is a better formated version of the 1981 B/X rules.

@Pelle: Thanks, I’ll take a look

Justin Alexander : have you read the new old school essential ? Is there this old instruction for dungeoncrawling, particularly the creation of a donjon inside ?

Pteryx says:

“The blind spot you describe is also why I’ve been thoroughly stymied in my attempts to ask people how to give the parts of an investigative scenario that AREN’T clue-finding enough structure to help my players understand what, on a basic level, they should be doing with clues once they have them. Because apparently discussing what the clues might mean with the other PCs, comparing them with other clues, coming up with theories to falsify, finding ways to get more information about the clues they do have, or even so much as rolling knowledge skills to see if PCs might have insights about clues that their players wouldn’t think of are not obvious to most people. In short, I’d like a discussion-at-HQ/whispered-discussion-around-the-corner structure to go with the investigate-the-scene structure… and I can’t seem to get ANYONE to understand this. At worst, it just comes back to people insisting Gumshoe is the Holy Grail of investigative gaming, which in this particular case strikes me as akin to saying that the way to solve the problem of not having peanut butter is to just spread the jelly faster.”

I’m writing an article about this that has a working title of “clue clues”. I identified that when players get a clue, say the matchbox with the name of the casino on it, what drives them t think “oh, this must mean something is happening at the casino”? What makes them even look at a matchbox on the table? There are some detecting procedures that players could have as a handbook, build a context, find information that confirms the context or suggests its wrong, use the context, especially if affirmed, to drive how you look for new clues, use the context, if affirmed, to give clues meaning.

clues -> context

context

-> where to look for clues

-> identifying it is a clue

-> groking the meaning and importance of the clue -> the desired conclusion the clue is meant to convey

@Justin

do I have this right?

Play Structure – a structure that players directly work with

Scenario Structure – a structure that a GM works with to build scenarios

Game Structure – all of the above

Coming to the conversation years later, but there are some structures that have appeared before and currently.

Chases have had structures built around them. The oldest I remember is the James Bond 007 game from Victory Games in the early 80s. The most recent is Savage Worlds (although it wasn’t in the initial edition I don’t think and I’m too lazy to go into the other room and look).

One very interesting system, which is an extrapolation of the basic 2d6 reaction check in OD&D, is On The Non-Player Character by Courtney Campbell. It provides definitions for type of simple social interactions with resolution, a way to determine how many you get (basically, the number of the reaction roll before the NPCs move on with their own agendas), and how to convert multiple interactions over longer time periods with the same NPCs into relationships. I use it regularly, including adapting it in a long 4e game.

I also like the structure of a skill challenge from 4e, but none of the versions we got really worked well. I’d done some kitbashing and had a couple of instances where I thought they worked out. One interesting idea I picked up from them is they cannot stop the adventure, just provide either benefits if succeeded or penalties if failed. I didn’t really get that until I watched Matt Coville’s video on them.

[…] system? One could say that it is in the name, ‘Dungeons’ and ‘Dragons’, but plenty of other bloggers have gone into the problems of the game no longer teaching people how to pl…, and how the mechanics of attrition seem to be fading away in favour of more narrative approaches. […]

[…] excellent series of articles on the Alexandrian on structure (/ procedure) in RPGs. This one in particular might give an idea of the lack of procedure, but I’d recommend all of them as a good […]

Can’t believe I happened to come across this post by searching Lost Mines of Phandelver here, very fascinating. Actually, it’s made me realise that despite purportedly having started to run a “megadungeon”, there are actually no dungeoncrawling systems in my campaign – just combat and essentially teleporting between one scene and the next. I guess this is the consequence of being a new player that only ever tried 5e. Maybe I should try and mix in some kind of concept of dungeon turns (I was already trying to make time important in the dungeon, but it was mostly just random encounters and DM fiat). Very useful post for all new DMs/players!

@XaviT: My new book, So You Want To Be a Game Master, not-so-coincidentally includes a complete dungeon procedure with fully developed dungeon turns.

I’m biased, but it might be worth checking out! 😉

@Justin Alexander: Ooh, I was already considering buying the book, but this certainly seals the deal for me. Definitely going to be worth it.