It’s your first chance to see what SO YOU WANT TO BE A GAME MASTER will look like on your shelf this fall! It’s the book that every GM, whether they’re taking their first step or just looking to take their game to the next level, will want to own.

Cover Reveal: So You Want To Be a Game Master?

Advanced Gamemastery – Dilemma Hooks

Force your D&D players to immediately start thinking about your scenario and making meaningful choices! ENnie Award-winning RPG designer Justin Alexander reveals the secret technique of using dilemma hooks in your adventures.

ADDITIONAL VIEWING

Surprising Scenario Hooks

Better Scenario Hooks

The Lion, the Witch, and the Scenario Hook

Running Mysteries: Enigma

Since writing the Three Clue Rule, I’ve spent just over a decade preaching the methods you can use to design robust mystery scenarios for RPGs that can be reliably solved by your players.

Now, let me toss all that out the door and talk about the mysteries that your players don’t solve. And that, in fact, you’re okay with them not solving!

These generally come in a couple different forms.

First, there are unsolvable mysteries. These are mysteries that you don’t WANT the players to solve. There can be any number of reasons for this, but a fairly typical one is that you don’t want them to solve the mystery yet. (For example, because you don’t want to reveal the true identity of the Grismeister until near the end of the campaign.)

Unsolvable mysteries are easy to implement: You just don’t include the clues necessary to solve them.

The other type of mystery we’re talking about is structurally nonessential. These are mysteries that the PCs can, in fact, solve. They’re revelations that the players are completely capable of figuring out.

But it’s possible that they won’t.

And that’s OK.

In fact, it can greatly enhance your campaign.

It’s OK because structurally nonessential revelations are, by definition, not required for the players to successfully complete the scenario: Knowing that the Emerald Pharaoh loved Sentaka La and arranged for her to buried alive after his death so that they could be reunited in the afterlife is a cool bit of lore, but it’s not necessary in order to complete The Doom of the Viridescent Pyramid.

Note: A corollary here is that structurally nonessential mysteries don’t need to obey the Three Clue Rule (although they certainly can and I’d certainly default to that if possible).

But if it’s a cool bit of lore, why wouldn’t we want to force the players to learn it?

When we, as game masters, create something cool for our campaigns, there’s a natural yearning for the players to learn it or experience it. That’s a good impulse, but it’s also a yearning that, in my opinion, we have to learn how to resist. If we force these discoveries, then we systemically drain the sense of accomplishment from our games. Knowledge is a form of reward, and for rewards to be meaningful they must be earned.

THE POWER OF ENIGMA

More importantly, the lack of knowledge can often be just as cool as the knowledge itself.

An unsolved mystery creates enigma. It creates a sense of inscrutable depths; of a murky and mysterious reality that cannot be fully comprehended. And that’s going to make your campaign world come alive. It’s going to draw the players in and keep them engaged. It will frustrate them, but it will also tantalize and motivate them.

Creating enigma with strategically placed unsolvable mysteries can be effective, but I actually find that having these enigmas emerge organically from structurally nonessential mysteries is usually even more effective:

- What’s the true story of how the Twelve Vampires came to rule Jerusalem?

- How did the Spear of Destiny end up in that vault in Argentina?

- What exactly was Ingen doing on Isla Nublar in Jurassic Park III?

- Who left these cryptic messages painted on the walls of the Facility?

The technique here is simple: Fill your scenarios with a plethora of these nonessential mysteries. (You can even create a separate section of your revelation list for them if you find it useful, although it’s not strictly necessary since you have no need to track them.) At that point, it becomes actuarial game: When including a bunch of these in a dungeon, for example, it becomes statistically quite likely that the PCs won’t solve all of them.

The ones they don’t solve? Those are your enigmas.

In my experience, the fact that these mysteries are, in fact, soluble only makes the enigma more effective. I think that, on at least some level, the players recognize that these mysteries that could be solved, and that invests the enigma with a fundamental reality. It’s not just the GM choosing to thwart you. The reality of that solution — and the fact that you, as the GM, know the solution — also has a meaningful impact on how you design and develop your campaign world.

(Which is not to say that there isn’t a place for the truly inexplicable and fanciful in your campaign worlds. Check out 101 Curious Items, for example. But it’s a different technique, and I find the effect distinct.)

ADDING MYSTERY

In the end, that’s really all there is to it, though: Spice your scenarios with cool, fragile mysteries that will reward the clever and the inquisitive, while forever shutting their secrets away from the bumbling or unobservant. When the PCs solve them, share in their excitement. When the PCs fail to solve them, school yourself to sit back and let the mystery taunt them.

You can, of course, make a special effort to add this kind of content, but I generally take a more opportunistic approach. I don’t think of this as something “extra” that I’m adding. Instead, I just kind of keep my eyes open while designing the scenario

- Here’s a wall studded with gemstones that glow softly when you touch them. Hmm… What if pressing them in a specific order had some particular effect? What could that be?

- This was a laboratory used by Soviet scientists engaged in post-Chernobyl genetic experimentation. Can the PCs figure out exactly what project they were working on here? And what WAS that project, exactly?

- This Ithaqua cult was founded in 1879. Hmm… Who were the cult founders? How did they first begin worshiping Ithaqua?

In the full context of a scenario, these aren’t just a bunch of random bits or unrelated puzzles. They’re all part of the scenario, which inherently means that they’re also related to each other. Thus, as the PCs solve some of them and fail to solve others, what they’re left with is an evolving puzzle with some of the pieces missing. Trying to make that puzzle come together and glean some meaning from it despite the missing pieces becomes a challenge and reward in itself.

This also means that, as you work on this stuff, you’re refining, developing, and polishing the deeper and more meaningful structure of the scenario itself.

On a similar note, this can also help you avoid one of my personal pet peeves in scenario design: The incredibly awesome background story that the PCs have no way of ever learning about.

This has been a personal bugaboo of mine ever since I read the Ravenloft adventure Touch of Death in middle school: This module featured what, at least at the time, I thought was an incredibly cool struggle between the ancient mummy Semmet and the Dread Lord Ankhtepot. I no longer recall most of the details of the module, but what I distinctly remember is the moment when I realized that there was no way for the PCs to actually learn any of the cool lore and background.

In practical terms, look at the background you’ve developed for your scenario: If there are big chunks of it which are not expressed in a way which will allow the players to organically learn about it, figure out how the elements of the background can be made manifest in the form of nonessential mysteries. Not only is this obviously more interesting for the players, but actually pulling that back story into the game will give the scenario true depth and interest.

If you put in the work, you win twice over. And then your players win, too.

Everybody wins.

This article has been revised from Running the Campaign: Unsolved Mysteries.

Random GM Tip – Inner Monologue Prompts

A roleplaying game, at its heart, lies at an interstice between game and conversation: In a conversation, we informally take turns sharing information. In a game, we formally take turns using the mechanics of the game. Roleplaying games dance freely between these two turn-taking dynamics, and in that dance the GM and the players are partners.

One of the ways I find this analogy useful is thinking in terms of action and reaction: The GM takes an action, and the players react to it on their turn. But then, of course, the GM takes their turn and, playing the world, reacts to what the PCs have done.

Often this conversational handoff is unprompted: The GM talks, the players talk, the GM talks again, and so on in a seamless back-and-forth.

In some cases, however, this will be prompted. Probably the most typical example is the GM, after presenting events in the world, saying something like, “So what are y’all doing?”

There can be a lot of different reasons for using a specific prompt, but it usually boils down to clarity in the handoff (“I’m done talking, so now it’s your turn,” in a fashion somewhat akin to saying “I’m done” at the end of your turn in a board game) or an effort to refocus the table (“let’s stop talking about which flavor of Cheetos is the best and get back to fighting the bilious zombies”). It’s kind of like saying “over” when you’re using a walkie-talkie.

Open prompts like this are almost always the purview of the GM, but more specific prompts from the players aren’t exactly uncommon. For example, while roleplaying their PCs chatting about recent events around the campfire, one of the players might turn to the GM and ask, “Do I know anything about King Roderick?”

GMs can also use a targeted prompt. Instead of prompting the table as a whole, the GM instead prompts a specific player: “What is Emily doing?”

Targeted prompts will formally arise from initiative counts or similar priority mechanics. (“Emily, it’s your turn.”) Even without formal mechanics, however, they can also commonly occur as a process of elimination: Everyone else has declared their action, and so, “While that’s happening, what is Emily doing?”

A specialized technique is the inner monologue prompt. This is a targeted prompt in which the GM asks a player to share and describe the inner life of their character.

- “Emily, how does the music in the tavern make you feel?”

- “What does Alfarr think of the minister’s proposal?”

- “Roscrucia, is this is the first dragon you’ve seen since the death of your parents? How does that make you feel?”

This technique doesn’t work well for all players and, personally, I only find it appropriate for certain campaigns. But when it does work, it can have amazing results!

If we were all Hollywood screenwriters we would have both the time and the talent to expertly reveal our characters’ inner lives through expertly crafted dialogue. But we aren’t and we don’t, so the best way to bring those character dynamics into the light may be to just cut directly to the point. It can also be a way of crystallizing and making strong emotional choices that might otherwise remain undefined and unrealized.

As noted, for some players this technique will be disruptive to their creative process and their relationship to their character. That should be respected. But one reaction that can be useful to push through is a feeling that this is “fake” or “artificial.” This is true, but, frankly, if it was good enough for Shakespeare, it’s good enough for us.

We do not, of course, have to whip out a soliloquy in blank verse. But the basic function of laying bare the character’s thoughts for the audience remains dramatically valid and emotionally powerful.

In this case, of course, the audience is our fellow players.

Thanks to Seven Wonders Productions on my Youtube channel for suggesting this topic.

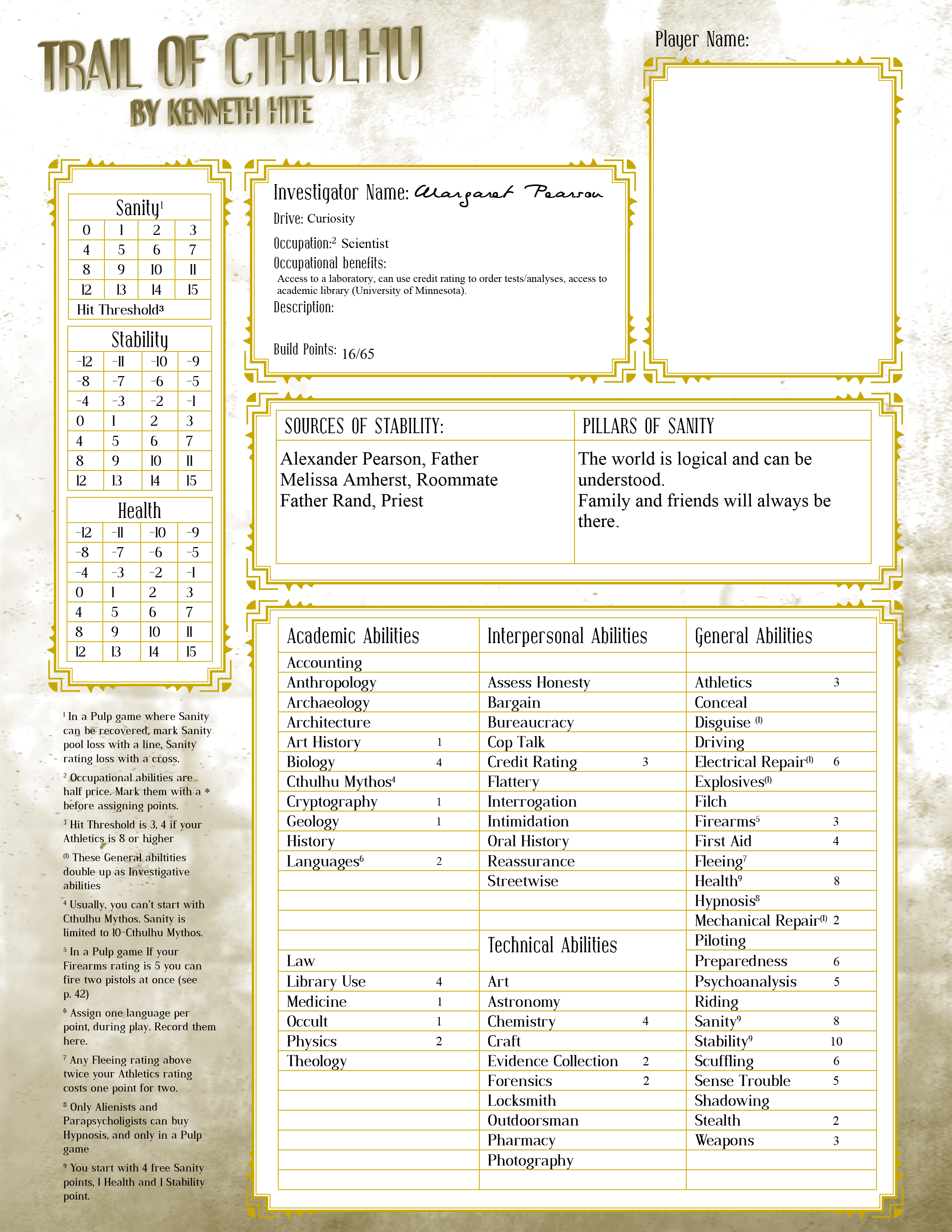

Left Hand of Mythos – Pregens – Part 2

Character Backgrounds by Chris Malone

FATHER GUSTAV, CLERGY

Age: 60

Gustav Rand was born in Austria in 1865, the youngest boy in a large Catholic Family. With little opportunity to distinguish himself above his brothers and sisters, he went to Seminary more as an eventuality than as a passion. It wasn’t until he joined the Jesuit order that he found some semblance of a calling, travelling the world as a missionary. Helping those in need and facing dangers with strength and faith connected him more to God than any scripture or devotional did. His diligence and fortitude recommended him for some of the most extreme places in the world, as he traveled to Ethiopia, Brazil, Guatemala, Australia, and other remote places.

As he aged and his body began to tire, he began to seek other opportunities to explore and express his faith. Father Rand’s exposure to numerous cultures granted him a degree of prestige within his order, and he could transition out of his missionary role and began a more scholarly calling. In 1913 Father Rand took a teaching position at Boston College, teaching archaeology and anthropology while undertaking various expeditions.

In 1919 he traveled with several students and faculty on one such expedition to Libya and the ancient city of Cyrene near modern Bengazi. It was here that Rand had his first encounter with obvious supernatural evil, as the unearthing of an ancient chamber resulted in release of an obviously violent entity that caused members of the dig to become violent and blasphemous. Only with the assistance of Maggie Pearson, a prodigal student, and the strength of will were you able to successfully perform an ancient rite uncovered in scrolls at the site and banish the foul creature. While many might have found these events a challenge to the faith, Rand found them affirming; he had always known supernatural evil exists. What ended up shaking his faith was the response of his Order. Upon filing a report and wishing to further examine the site and document the event, The Jesuit Order terminated the expedition and commanded Rand to destroy all evidence of what had happened, and commanded him to remain silent.

Rand did mostly as ordered, only retaining private notes and few of the scrolls that helped him bind and banish the creature. Shortly thereafter Father Rand left the Jesuit Order and petitioned to become a diocese priest. The Archdiocese of St. Paul had recently suffered significant attrition, and so he was assigned there. Father Rand quickly insinuated himself into several philosophical circles and serves as an occasional guest lecturer at local colleges. To his surprise, Maggie Pearson arrived in the Twin Cities several years after he did.

Through his connections to Max Bruener, a recent friend and lay student, Rand has found himself the most curious assistant in a private investigation firm run by Jake Connor. Several years ago you were approached by Max to help parse out some writings that were found at the scene of several disappearances. You helped identify the texts and continued with the case, surprised to find yourself again in the company of Maggie Pearson, who happened to be Jake’s cousin. The case was most unusual; two seemingly separate instances of a young man and a young woman disappearing led Jake and his companions to a secretive cult operating within the Freemasons that was engaging in human sacrifice in the name of some esoteric and foul deity. Jake and company acted quickly and rescue one of those who had disappeared (the other, sadly, was long dead) and bring the perpetrators to justice. Now the local police come to Jake and company with queries or leads into strange or occult cases.

RELATIONSHIPS

Jake Connor — Jake’s a veteran and a private investigator. Father Rand finds Jake’s passion and energy refreshing, but sometimes finds himself frustrated with Jake’s lack of introspection and philosophical inquiry. Regardless, Rand knows that Jake is courageous and respects his strength.

Maxwell Bruenner — Max is a wealthy young man in charge of a manufacturing business left to him by his father. Max came to Father Rand during a spiritual crisis, seeking answers to the things he saw during the War and trying to understand his place in a seemingly cruel world. Father Rand has helped to guide Max’s inquiry, encouraging exploration of the spiritual and the unseen, as opposed to coercing or suggesting that he become a Catholic. This has formed a strong bond between the two. The only real point of contention is Max’s vocal agreement and support of Prohibition, a point which you two disagree upon, but you feel much less passionate about. You took on vows of poverty and celibacy, not sobriety.

Maggie Pearson — You first met Maggie in 1917 when she was a student in your Early Religions course at BC. An apt student with energy and passion, you quickly became fond of the young girl distinguishing herself in a place that only just started allowing women to attend. On the Libya expedition, she handled herself smartly, helping you eradicate the entity before it could cause serious harm. Since your reintroduction to her in St. Paul you see her regularly, either when working cases with her cousin or on your regular Wednesday luncheons.

MARGARET “MAGGIE” PEARSON, SCIENTIST

Age: 26

Maggie grew up in Boston, the eldest of four daughters, in a middle-class family, her father a dentist with her mother at home. Showing a strong mind with an aptitude for critical thought and quick wits, she claimed a place among the first class of female students at Boston College. Despite the hostile environment, oppressive curfews, and constant scrutiny from the administration, Maggie thrived in an environment that rewarded her intellect and provided her new experiences. Virtually all her professors were inimical towards her, save for one notable exception.

Her freshman year met Father Gustav Rand, a Jesuit who was teaching archaeology and anthropology. He treated her fairly and with praise and encouragement, showing her respect and deference that few others would. Even when not studying under Father Rand, Maggie would regularly meet with Father Rand and discuss her studies.

In 1919 Rand invited Maggie on an expedition to Libya. With much cajoling, pleading, and threatening Maggie convinced her father to allow her to go, and it was there that she faced a life-changing event. During the dig at Cyrene, near modern Bengazi, strange things began to happen. Workers and other students acted violently, and several people became hurt. After a horrifying experience where she felt the alien presence of some foul thing pressing into her mind, Maggie convinced Father Rand that a supernatural threat was present. Working together, Maggie and Rand used some ancient scrolls and a bit of alchemical knowledge to destroy the entity. Maggie returned to BC shaken, but confident in her strength and ability.

Shortly afterward, Father Rand left the Jesuit Order and Boston College. While upsetting, this event only spurred Maggie on to finish her bachelor’s degree and leave that place. Following her graduation from BC, she managed to land a graduate position at the University of Minnesota, where she teaches and studies today in pursuit of her doctorate in the Sciences. Her decision to move to Minnesota was partly prompted by the fact that her father refused to let her go somewhere without family, especially without a strong male presence to guide her to make sure she remains virtuous. To this end, her cousin Jake Connor serves as a chaperone and confidant. A larger part of her decision was informed by her correspondences with Father Rand, and her desire to reconnect with him.

About two years ago Maggie began helping her cousin Jake with the private investigation business that he owns and runs. During an odd case involving the disappearance of a couple of seemingly unconnected people, Maggie identified a rare sedative used on both victims, and used her resources to find the supplier (and purchaser) of that sedative. The case turned strange, as the two people who disappeared were involved with an inner sect of the Freemasons, which turned out to be pursuing occult ritual and human sacrifice. You and the others were able to disrupt the ritual and stop them, but only after one of the kidnapped victims were killed. Since then you have been learning how to handle yourself in a fight and have helped Jake from time to time.

RELATIONSHIPS

Jake Connor — Your cousin Jake is a veteran of the War and a private eye. He is protective of you and at times seems to regret his decision to involve you in his line of work. You love him, but he can sometimes frustrate you with his superficial thinking. His vehement anti-Prohibition rhetoric can sometimes get tiresome as well, as you find that the need to drink is a silly diversion from rationality.

Maxwell Bruener — Max is Jake’s friend and helps on cases sometimes. While he seems kind and gentle, you have seen his strength and courage during the Freemason case when he charged into a room full of cultists and fought them off with his bare hands. His philosophical inquiries are engaging, and overall you find him a pleasant enough fellow to spend time with.

Father Rand — Father Rand is more than a mentor or a professor to you, he is your confidant and guide. At times you have wondered if you might have more than a reasonable amount of affection towards him, but you quickly squash these thoughts with study and diversion.

DOWNLOAD THE CHARACTER SHEETS

(PDF)

If you enjoyed The Left Hand of Mythos, please consider becoming a patron.

Patrons have exclusive access to a PDF collection of the adventure (including prop pack and other bonus material).

Archives

Recent Posts

- Games Unplugged Review – Lejendary Adventures: Beasts of Lejend – Cyclopedia of Creatures

- Campaign Status Module: Trinity Toolbox

- Video Review: Brindlewood Bay

- Bonus Videos! – Mothership & Crooked Moon

- Games Unplugged Review: Heavy Gear – Tactical Space Support: Space Warfare

Recent Comments

- on Review: The Shattered Obelisk – Addendum: Unkeyed Dungeons

- on Rules vs. Rulings?

- on Review: The Shattered Obelisk – Addendum: Unkeyed Dungeons

- on Review: The Shattered Obelisk – Addendum: Unkeyed Dungeons

- on Dungeons: Player Mapping

- on Dragon Heist Remix – Part 3: Faction Outposts

- on Ex-RPGNet Review: The Speaker in Dreams

- on Roleplaying Games vs. Storytelling Games

- on Storm King’s Remix – Part 4: Hekaton is Missing!

- on How to Prep – The Haunting of Ypsilon-14