Go to Part 1

TO WAR!

Shadow of the Dragon Queen takes place during the Siege of Kalaman.

No, not the Siege of Kalaman in 352 AC where Laurana is the general and the Dragon Armies deployed their flying citadels for the first time. This is an earlier Siege of Kalaman that takes place in 3-mumble-mumble AC, when a completely different flying citadel showed up for the first time, shredding absolutely everything we know about this continuity.

Ironically, I think Kalaman was chosen for this campaign because so little was established in the Dragonlance Saga about what happened there during the War of the Lance. Across all fourteen of the original modules, there’s only like a dozen paragraphs you would have to keep track of to keep things consistent, so it’s almost impressive in a way that they nevertheless managed to screw it up.

(I’ll stop calling out rotten continuity at this point, for that way lies madness.)

The other reason to set a campaign here is that Kalaman is basically the point closest to the Dragon Armies at the beginning of the War of the Lance which is NOT conquered by them. Go any closer to the draconian homelands and the PCs can’t save the day. Go any farther away and you can’t get away with telling a story of the early days of the war where people are still coming to grips with the true nature of the Dragon Queen’s threat.

The point is that Shadow of the Dragon Queen is set in the heart of a war, and the PCs will be no strangers to the battlefield. Over the course of the campaign, there will be twelve major battles that the PCs will be part of, and you’ll have two options for handling them.

First, as I mentioned, there’s the Warriors of Krynn boardgame, which contains each of those battles as individual scenarios. I’m likely going to do a separate review of the board game and will take a closer look at how it integrates with Shadow of the Dragon Queen there.

But you don’t need to buy Warriors of Krynn to run Shadow of the Dragon Queen. The book includes a system of battlefield encounters which can be run as standard D&D combats. These consist of four parts:

But you don’t need to buy Warriors of Krynn to run Shadow of the Dragon Queen. The book includes a system of battlefield encounters which can be run as standard D&D combats. These consist of four parts:

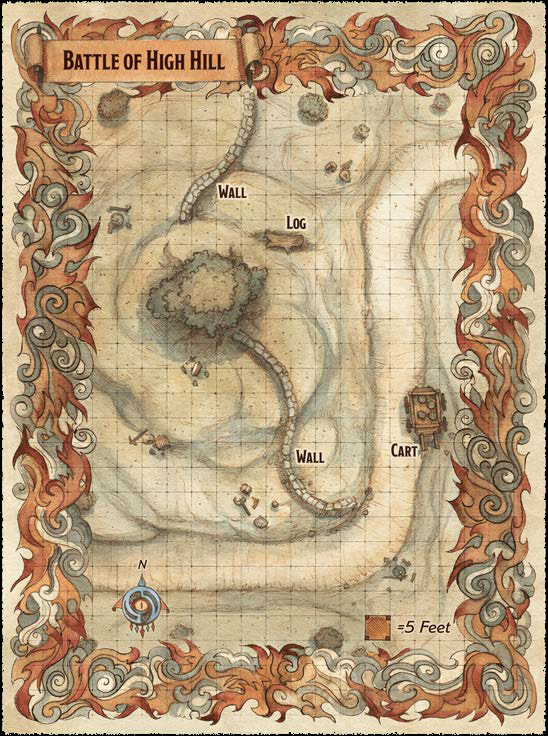

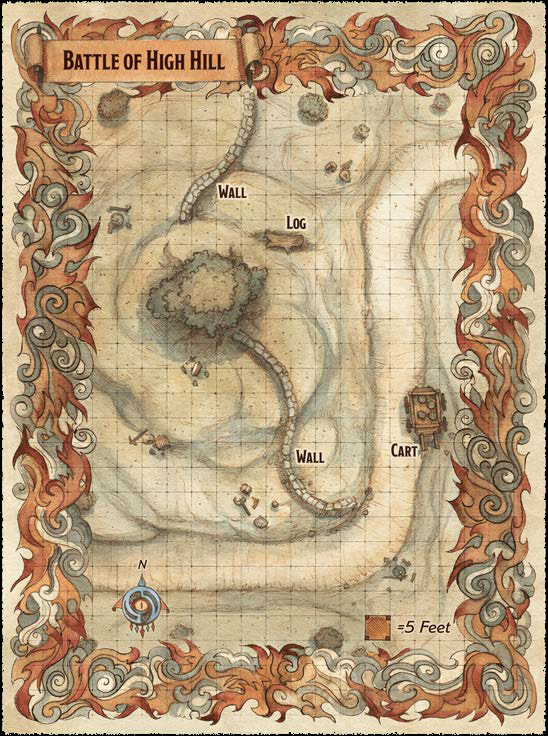

The battlemap. These are gorgeously rendered and are roughly the dimensions you’d expect in any other D&D battlemap.

Notably, however, the battlemaps have a 15-foot rim on all sides referred to as the fray. This is the first way in which these battlefield encounters represent the chaotic melee swirling around the PCs: Each fray has unique properties, generally being difficult terrain and requiring a saving throw to avoid damage if a character enters the area.

There are also the battlefield events, which occur randomly whenever a character enters the fray or at initiative count 0 on each round. These include things like:

- A volley of arrows falls on a random character’s position.

- Low-flying dragonnels flee across the battlefield.

- A draconian dragon rider falls from their mount, plummeting out of the sky and landing on the battlefield.

- An injured member of the PCs’ army crawls onto the battlefield, begging for aid.

Finally, of course, there’s the encounter itself. Sometimes this is a single group of bad guys; in other cases there’ll be a scripted sequence with additional bad guys showing up over time. Either way, when the bad guys are all defeated, the encounter (and the wider battle) come to an end.

This seems like a really simple structure, but conceptually it packs a big punch. There’s a lot you can do with just these few simple tools to bring radically different battlefields to vivid life in your campaign.

The one thing I would like to be able to say is that the outcome of these battlefield encounters have an effect on the outcome of the wider battle. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. Which is perhaps unsurprising, because…

ALL ABOARD, FOLKS!

… the campaign is horrendously railroaded.

By which I mean both that the railroading is relentless and all-encompassing, but also that the methods they use to force the railroad down your throat are just hopelessly awful.

Phrases such as “encourage the characters to” and “it’s up to the characters to…” and the like seem to be the book’s favorite ways to signal the DM that the time has come to take the character sheets away from the irresponsible players.

Different people will have different reactions to this kind of stuff, but for me the absolute worst type of railroading is when the DM takes control (directly or indirectly) of what your character says. (Because, honestly, what’s left at that point? We’re literally just sitting at the table watching someone awkwardly talk to themselves.) And Shadow of the Dragon Queen absolutely loves this.

For example, the PCs have been railroaded into a debate with NPC military commanders about what the next logical course of action should be. The NPCs make their arguments, and then the DM is instructed to:

…encourage the characters to make the case that Lord Soth is a threat and the Dragon Army’s plans to the north shouldn’t be taken lightly.

But then the writers think to themselves, “Maybe the players won’t take the hint from the clue-by-four we’ve smashed into their faces. Or maybe the Dungeon Master won’t have the guts to put the gun to their heads and keep them in line.”

The answer, of course, is to cue up a GMPC. So, for example, even after you’ve “encouraged” the players to say their scripted lines, it’s an NPC who swoops in and gets to be the hero of the scene:

Darrett then asks Vendri to let him take the characters and a contingent of troops into the Northern Wastes to investigate whatever the Dragon Army wants there. [Vendri] asks the PCs to leave while she and Darrett discuss details…

I cannot emphasize enough that this is not one or two isolated incidents: It is the entire campaign. Just an endless, mind-numbing litany of blow-by-blow descriptions of how the authors anticipate/demand each scene be played out.

“The NPCs will say. Then the PCs will say. Then the NPC will say. Then the PCs will say.”

This is interspersed liberally with “the PCs can roleplay or they can make a Persuasion/Intimidation/whatever check,” which (a) is just bad praxis (rolls and roleplaying work together; it’s not either-or) and (b) is completely pointless anyway, because the check result never seems to vary how the conversation plays out!

And I just want to take a moment to say something truly from the bottom of my heart:

Fuck Darrett.

This prick gets attached to the PCs like a cancerous mole early in the campaign. He tags along as a sidekick squire, but then, suddenly, he’s the main character: It’s him, not the PCs, who gets promoted based on their adventures together. It’s him, not the PCs, who’s scripted to save Lord Bakaris’ life. Before you know it, he’s the PCs’ boss, ordering them around, making all the important decisions, and continuing to scoop up all the accolades.

So, again: Fuck Darrett.

And there’s basically an endless parade of these jackasses through the entire campaign.

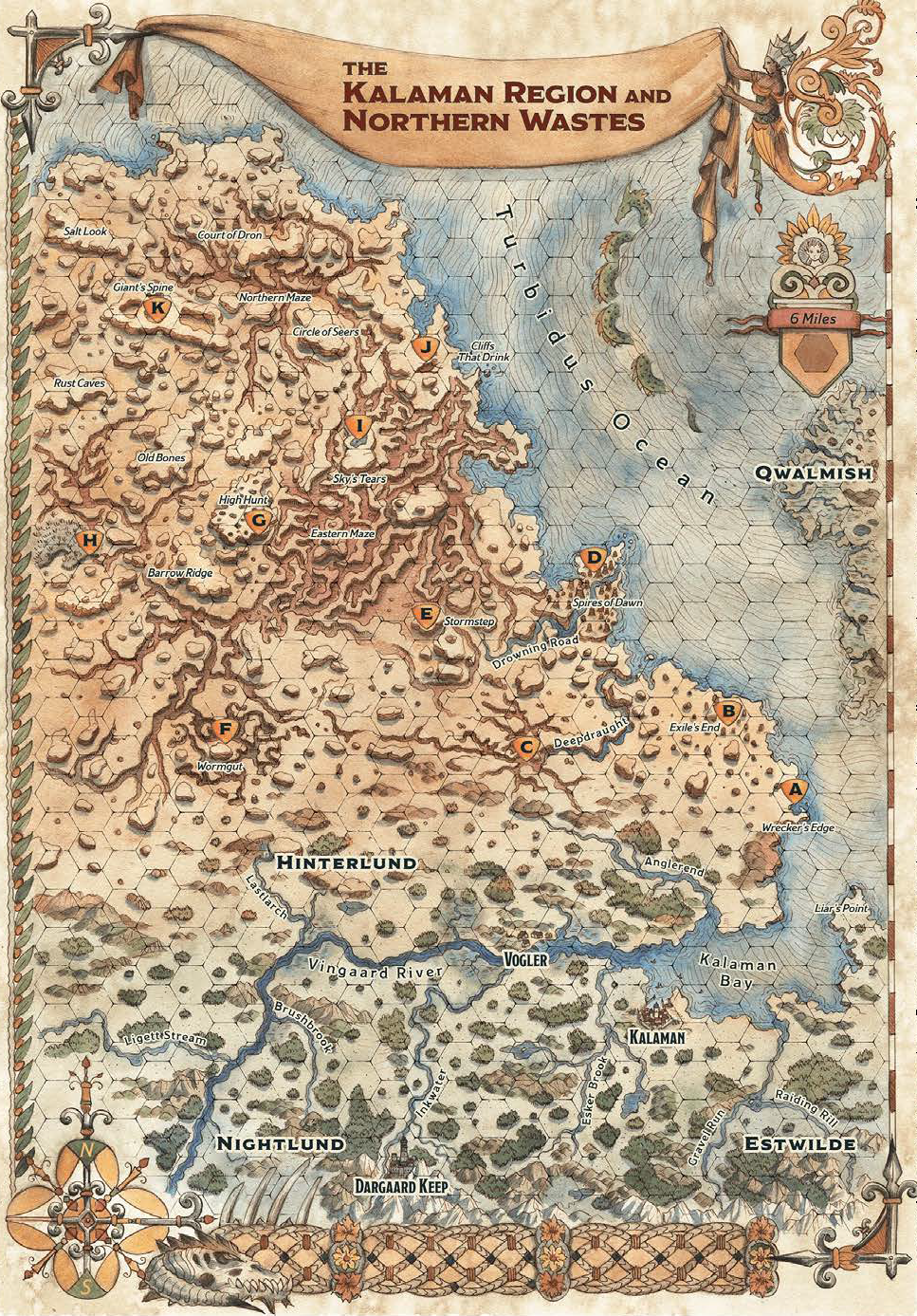

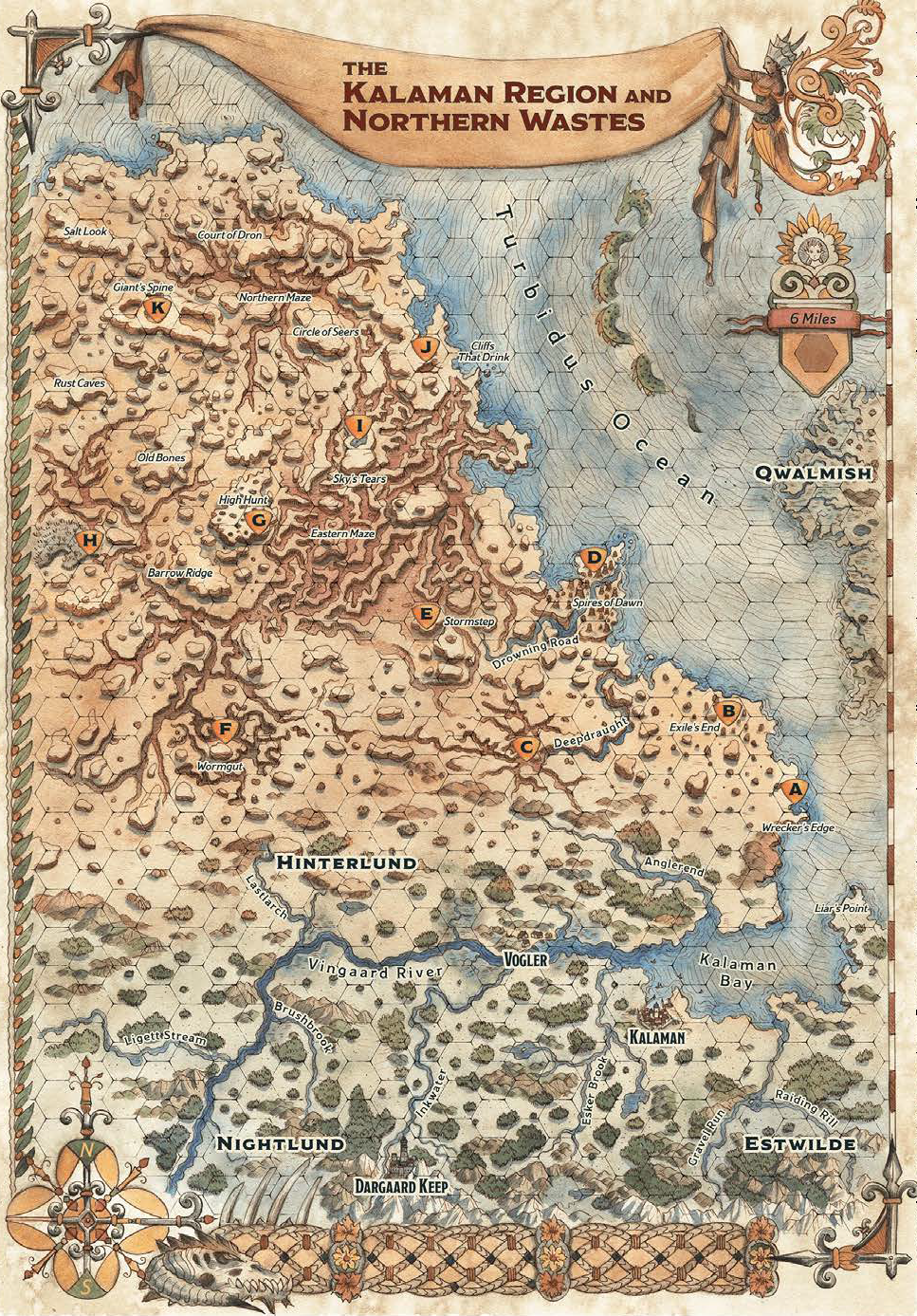

About midway through the book, for example, Darrett says, “See that huge hexmap over there? I’m going to stay here on the boat. Y’all go and explore for a while!” For one glorious moment, the players will rejoice! The fetters have come off! Not only do the PCs finally get to ditch Darrett, they’ll be in control of their own destiny! They’ll get to make their own choices!

About midway through the book, for example, Darrett says, “See that huge hexmap over there? I’m going to stay here on the boat. Y’all go and explore for a while!” For one glorious moment, the players will rejoice! The fetters have come off! Not only do the PCs finally get to ditch Darrett, they’ll be in control of their own destiny! They’ll get to make their own choices!

Except no. Because the authors are so terrified of the players having the slightest bit of agency that literally eight paragraphs later a brand new GMPC pops up with detailed instructions on EXACTLY THE ORDER IN WHICH YOU WILL CONDUCT YOUR “EXPLORATION!”

There’s even a little scene so that, if the PCs are confused about who their new master is, Darrett will helpfully explain it to them.

The whole thing is so grotesquely pointless that it almost feels as if the authors are being deliberately petty. As if they have some personal grudge against the players.

THE BORING BITS

As I look over my notes for Shadow of the Dragon Queen and flip through the book to refresh my memory, I can see that it’s studded with big, impressive set pieces:

- huge battles,

- dragonriding duels,

- flying cities,

- gnomish siege weapons,

- ruined cities,

and more!

Just looking through this list, it seems as if this campaign should be a thrill-fest from one end to the other.

So why did I find the book so utterly stultifying to read?

Largely because the medium is the message. When I read an adventure book like this, what I’m thinking about is the experience of running it at the table. And the picture Shadow of the Dragon Queen paints of the actual play experience isn’t a pretty one.

Yeah, the set pieces are shiny and cool in an abstract sense. But when I’m reduced to a mute audience either watching somebody else do all the cool stuff or stuck as a helpless puppet unable to have any effect on what’s happening, they lose their luster.

For example, consider the big finale of the campaign:

First, the PCs fight and fight and fight and fight to prevent the bad guys from taking control of the flying citadel!

And it doesn’t matter, because an unskippable cutscene is triggered and they’re forced to just watch while the bad guy activates the flying citadel helm.

But that doesn’t matter, either, because it doesn’t work and the citadel is falling apart all around them!

But that ALSO doesn’t matter, because after the PCs escape from the collapsing citadel, they turn around and see a different bad guy flying off in a completely different citadel!

Whoopsie-doopsie!

You can almost be impressed by the skill it takes to build up so many levels of irrelevancy. (Almost.) But they aren’t even done!

See, the PCs might think to themselves, “We’ve gotta stop the other citadel!” and rush to do that. That’s not the plot, though, so the DM is instructed to use endlessly respawning death dragons “that attack until the characters retreat.” The defenses are too strong! All you can do is watch helplessly while dragonnels ferry troops from the ground into the citadel!

Three pages later, though, after the entire dragon army has transferred itself into the flying citadel and its defenses are even more impregnable? Now it’s time to attack, and so a gaggle of GMPCs show up and give the PCs their marching orders.

Sure, after all that, the dragon-riding duel with Dragon Highmaster Kansaldi Fire-Eyes (complete with pre-scripted conclusion) has a cool illustration, but I honestly find it impossible to get legitimately enthused about it.

When the book goes to such elaborate lengths to scream, “THIS IS ALL POINTLESS AND NOTHING YOU DO MATTERS!” eventually you believe it, no matter how pretty the two-dimensional set painting is.

Grade: D-

Project Lead: F. Wesley Schneider

Writers: Justice Arman, Brian Cortijo, Kelly Digges, Dan Dillon, Ari Levitch, Renee Knipe, Ben Petrisor, Mario Ortegon, Erin Roberts, James L. Sutter

Publisher: Wizards of the Coast

Cost: $49.95

Page Count: 224

A guide to grades here at the Alexandrian.