Now that we have a custom campaign structure for a “Between the Stars” campaign, let’s turn our focus to the scenarios that will be triggered by that campaign structure.

With quite a few of these scenarios, of course, we can use scenario structures that we’re already familiar with: Someone is murdered on board; grab our scenario structure for mysteries. The ship stumbles across a wandering asteroid studded with alien architecture; whip out the maps for an old-fashioned dungeoncrawl. We might want to give some thought to the types of hooks we can use to initiate each scenario narratively, but there’ll be no need to reinvent the wheel in designing the scenarios themselves.

(Random thought: If we’re looking for a semi-generic structure for constructing scenario hooks we could define them according to (a) when they’re triggered; (b) what officer will receive the trigger; and (c) what the hook is. For example, a scenario in which the PCs are approached to smuggle a cargo might be triggered in dock before the voyage starts; target the cargomaster; and take the form of a comm call asking for a meeting at a dockside bar. The “asteroid of alien architecture” might be hooked with the navigator making a Sensors check (on a success they detect the asteroid a fair distance away; on a failure they stumble too close to it and get caught in an automated tractor beam). A murder scenario might be hooked with the security officer making a Security check (success indicates they find the body on a routine sweep; failure indicates that a random passenger finds the body).)

For other scenarios, however, it may be useful to give some thought customizing new scenario structures. As an example of that, we’re going to look at the hypothetical example of hijacking scenarios. Before doing that, however, I want to make a couple of particular points.

First, we’ll want to remember that the default goal of the campaign’s macro structure is to successfully run a ship in order to maximize profit. Which means that scenarios and hooks that either threaten the PCs’ profit or offer them opportunities for more profit will be most successful.

Second, I want to note that this entire section of the essay is entirely hypothetical: If this stuff were to be put to a proper playtest, I have little doubt that we’d discover that some of it doesn’t work in practice and other stuff could be greatly improved. That’s just part of the process.

SCENARIO STRUCTURE: HIJACKING

What we’re looking at here is any scenario where passengers, stowaways, or members of the crew attempt to take control of the ship.

If the ship were relatively small in size, we could probably run this using location ‘crawl techniques. In other words, we could take a fully keyed map of the ship and then run the actions of the PCs and hijackers in “real time” so to speak. This would be appropriate for something like Air Force One.

But let’s assume that the ship is larger and that we want to create experiences that feel more like Die Hard or Under Siege.

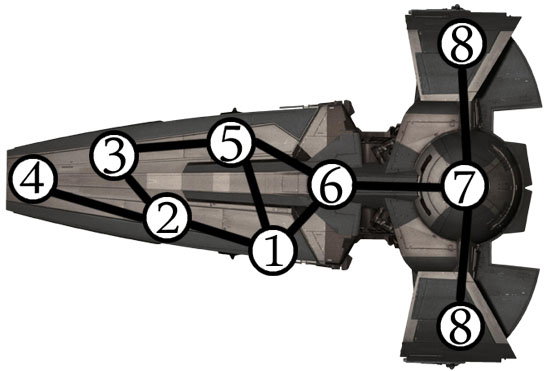

Node Map of the Ship: First, for purposes of navigation, let’s create a node map of the ship. This abstract representation of movement aboard ship will allow both PCs and hijackers to make meaningful decisions about where they’re going and how they’re going to get there without getting bogged down in tracking things corridor-by-corridor and room-by-room. (Although for certain key areas – like the bridge of the engine room – we may still want to draw-up detailed maps for tactical purposes.)

With this map we can now key both nodes and the routes between nodes. We can also allow characters to secure and/or barricade specific nodes or routes. (So some routes to the bridge may be less heavily guarded than others, for example.)

We can also assign travel times between locations.

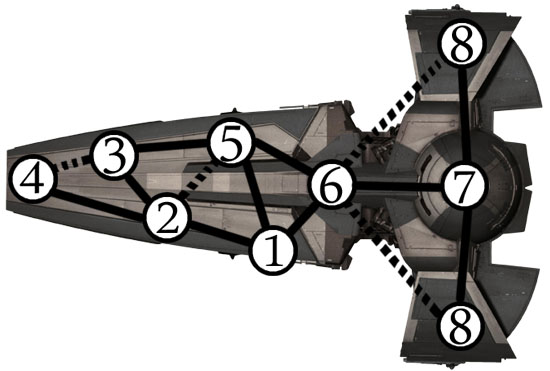

Shortcuts and Stealth Paths: Looking at our touchstones of Die Hard and Under Siege, we can see that a lot of the action is driven by protagonists seeking out alternative methods of moving around the structure (ventilation shafts, service corridors, burning holes through bulkheads, etc.).

We could try including these routes onto our node map of the ship, possibly by using dotted lines:

Or, for a simpler and more flexible solution, we could assume that the ship has sufficient structural complexity that secret routes can always be found: With a sufficiently high skill check, a character can either find a short cut (which reduces the amount of time it takes to get from one location to another) or a stealth path (which makes it possible to reach areas of the ship that have been blocked off in one way or another).

To this, let’s add a wrinkle: If effort is taken, certain locations can be secured. For example, in Aliens the last of the survivors attempt to seal up a portion of the colony so that they can survive long enough for a rescue ship to arrive. Of course, the aliens still managed to find a way in, so let’s make that an opposed check: If your effort to find a stealth a path into my area is better than my check to seal the area, then you’ve found something that I forgot.

Control of the Ship: For a simple structure, we could simply equate control of the ship with control of the bridge. But if wanted a more dynamic scenario, we could make it so that individual systems can be taken offline or supersede the bridge’s control from other locations in the ship. (For example, you might be able to gain navigational control from the engine room; knock communications off-line by getting to the receiver room; turn off life support from environmental control; or access the automatic security systems from the security center.)

Node Effects: On a similar note, we might want to define some specific game structures for special nodes. For example, if you can access the communications array and send a distress signal, what effect will that have?

Is gaining control of the automatic security systems something that can be automatically achieved in the security center? Does it require an opposed skill check? A complex skill check? If so, how much time do those checks take? (Would it give enough time for the bad guys to physically lay siege to the security center?) Do you have to do it compartment by compartment? Do we run the whole thing as a massive hacker-vs-hacker battle in virtual reality?

Do I prep the armory by simply having an inventory of available supplies? Or do we code something similar to a wealth check to see if a particular piece of desired equipment is available?

Random Encounters: Finally, I’m always a big fan of using random encounters to simulate the activity in complex environments. Whether it’s panicked pockets of prostrate passengers or roving hijacker enforcement teams, a well-seeded random encounter table can add unexpected twists and delightful chaos to the scenario.

OTHER SCENARIO STRUCTURES

Here are some other potential scenario structures for a “Between the Stars” campaign.

Bomb Onboard: Touchstones might include stuff like Die Hard With a Vengeance and Law Abiding Citizen. The actual mystery of identifying the bomber can probably use a standard mystery scenario structure, but what about the process of finding (and possibly defusing) bombs before they explode? What effect do bombs have on ship systems?

Plague: The Babylon 5 episode “Confessions and Lamentations” is a particularly poignant look at disease scenarios on spacecraft. “Genesis” from Star Trek: The Next Generation was a particularly stupid one. (On the other hand, TNG’s “Identity Crisis” shows the breadth of potential within the general idea.)

Lost in Space: Touchstones would include… well… Lost in Space. (Also, Poul Anderon’s Tau Zero.)

Collision in Space: Here you could probably lift some of the same structures for systems damage from the “Bomb Onboard” scenario structure to model collision damage.

Mutiny: We could probably lift large chunks from our “Hijacking” scenario structure

Smuggling: Both with the PCs engaging in smuggling and with NPC smugglers trying to use their ships to achieve their own aims.

If you’re feeling up for it, grab one of these and give it the same treatment we gave hijackings: Post it here in the comments or toss a link down there to wherever you do post it.

When I designed The Lost Hunt for Fantasy Flight Games, I launched the scenario by having an elven village attacked by a kehtal (a servitor of the demon gods of Keht). The idea was pretty simple: The PCs could then follow the trail of this murderous creature, which would lead them to the interdimensional rift in which the demon gods were imprisoned.

When I designed The Lost Hunt for Fantasy Flight Games, I launched the scenario by having an elven village attacked by a kehtal (a servitor of the demon gods of Keht). The idea was pretty simple: The PCs could then follow the trail of this murderous creature, which would lead them to the interdimensional rift in which the demon gods were imprisoned.