The thing I value most about the Old School Renaissance – and the reason I enjoyed exploring the ur-game of OD&D – is that a lot of valuable and experimental mechanics and game structures were functionally abandoned as the hobby and industry kind of dashed headlong towards a post-AD&D / post-Dragonlance homogenization.

So when I’m struggling with something like urbancrawling I find that it can be very useful to dip back into the primordial pool and poke around a bit to see if anything useful pops out.

KEEP ON THE BORDERLANDS

It’s interesting to note that the AD&D Dungeon Master’s Guide doesn’t actually include guidelines for urban adventures: Dungeon adventures, wilderness adventures, aerial adventures, waterborne adventures, underwater adventures, and even planar adventures all get coverage. Urban adventures? Nope.

It’s interesting to note that the AD&D Dungeon Master’s Guide doesn’t actually include guidelines for urban adventures: Dungeon adventures, wilderness adventures, aerial adventures, waterborne adventures, underwater adventures, and even planar adventures all get coverage. Urban adventures? Nope.

I believe this is because Gygax primarily saw cities as the hub around which adventures were based: You came back to the city to get supplies and hirelings. You left the city in order to have adventures.

Gygax’s handling of the Keep in Keep on the Borderlands seems to largely confirm this. Five specific points are given under “DM Notes About the Keep”:

I. Specific responses to PCs who break the law.

II. “Floor plans might be useful… exceptionally so in places frequented by adventurers.”

III. Rumors can be gained by talking to people at the Keep. (Example: “Talking with the Taverner might reveal either rumor #18 or #19; he will give the true rumor if his reaction is good.”)

IV. How to enter the Inner Bailey of the Keep and get a special mission from the Castellan.

V. After the adventure material in the module has been used up, you can “continue to center the action of your campaign around the Keep by making it the base for further adventures you devise”. Examples given include leading a war party to fight bandits, becoming traders operating out of the Keep, or exploring the wilderness to find additional adventures in the surrounding area.

(What I love about that fifth point is how casually Gygax drops the idea of three radically different game structures as potential avenues for developing the campaign. It’s very suggestive to me of how different the early GMs were in their approach to the game, compared to later “sequential dungeons” or “follow the plot” styles.)

In other words, the Keep is treated as a place for PCs to shop and as a place to gather information that will point them towards adventure.

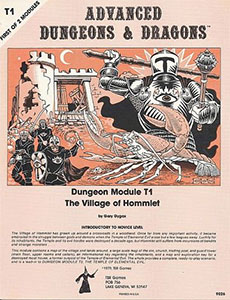

THE VILLAGE OF HOMMLET

T1 The Village of Hommlet, also by written by Gygax, was published around the same time that B2 Keep on the Borderlands was published and it shows a consistent methodology: Every building is keyed. The places “frequented by adventurers” are given floorplans. Rumors are keyed to specific individuals (replacing the generic rumor table). Basically, there are only two significant departures.

First, no specific response scenario is given for PCs breaking the law. This, however, seems to flow as a natural consequence of the lack of a central legal authority in Hommlet.

First, no specific response scenario is given for PCs breaking the law. This, however, seems to flow as a natural consequence of the lack of a central legal authority in Hommlet.

Second, there is a seemingly odd desire to itemize the valuable contents of every single commoner’s hut.

In combination, however, this actually makes sense: Instead of legal response scenarios, a lot of attention is given to alliances and friendships. So you get entries like, “He has 20 gold ingots (50 g.p. value each) hidden away in a secret hollow under the stone wall in front. He has become quite friendly with the magic-user, Burne.” The clear implication, at least to my eyes, is that if you mess with this guy or steal his shit, Burne’s going to come looking for you. (Whereas if you mess with his neighbor, who is a member of the Church of St. Cuthburt, you’ll be dealing with the Church.)

The underlying assumption here (and in a lot of early city modules) seems to be that some significant percentage of PCs are going to be murderhobos: B2 deals with that by specifying centralized legal repercussions. T1 assumes that the PCs will succeed in looting a house or two (and therefore specifies the loot), but also lays out a comprehensive social network that’s going to come looking for their blood.

This is mostly a digression, but it is interesting to note that having these sorts of explicit or semi-explicit structures in place for dealing with murderhobos is an essentially universal aspect in all of the early city modules I’m looking at.

THE FIRST FANTASY CAMPAIGN

Let’s turn our attention from Gygax and instead focus it upon Dave Arneson. Although not published until 1977, the First Fantasy Campaign “attempted to show the development and growth of his campaign as it was originally conceived”.

First, an important note: “By the end of the Fourth year of continuous play Blackmoor covered hundreds of square miles, had a dozen castles, and three separate Judges as my own involvement decreased due to other circumstances. But by then, it was more than able to run itself as a Fantasy campaign and keep more than a hundred people and a dozen Judges as busy then as they are today.”

Even with my experience running an open table supporting 30-40 players, the sheer scale of what the Blackmoor campaign was like in this timeframe is really difficult for me to wrap my head around. And we need to keep in mind its unusual needs and demands as we try to unravel what the city-based game structures of the campaign were.

We’ll start with this: Over the course of its first two years, Blackmoor “grew from a single Castle to include, first, several adjacent Castles (with the forces of Evil lying just off the edge of the world) to an entire Northern Province(s) of the Castle and Crusade Society’s Great Kingdom. As it expanded, each area (Castle’s first and then Provincial Counties) was given a pre-set Army. Later, the players were to organize their own forces based on experience and goodies procured enroute to their Greatness.”

We’ll start with this: Over the course of its first two years, Blackmoor “grew from a single Castle to include, first, several adjacent Castles (with the forces of Evil lying just off the edge of the world) to an entire Northern Province(s) of the Castle and Crusade Society’s Great Kingdom. As it expanded, each area (Castle’s first and then Provincial Counties) was given a pre-set Army. Later, the players were to organize their own forces based on experience and goodies procured enroute to their Greatness.”

In other words, the early dungeon-based portion of the game was designed to prepare characters for establishing Castles which would be used to raise Armies in order to participate in wargames. “The entire 3rd Year of the Blackmoor Campaign was to be part of a Great War between the Good Guys and the Bad Guys.”

So one of the primary uses for a city in Arneson’s campaign was to supply the Army.

In terms of how the Town of Blackmoor was actually run at the table, however, we are regrettably only given a half page of information.

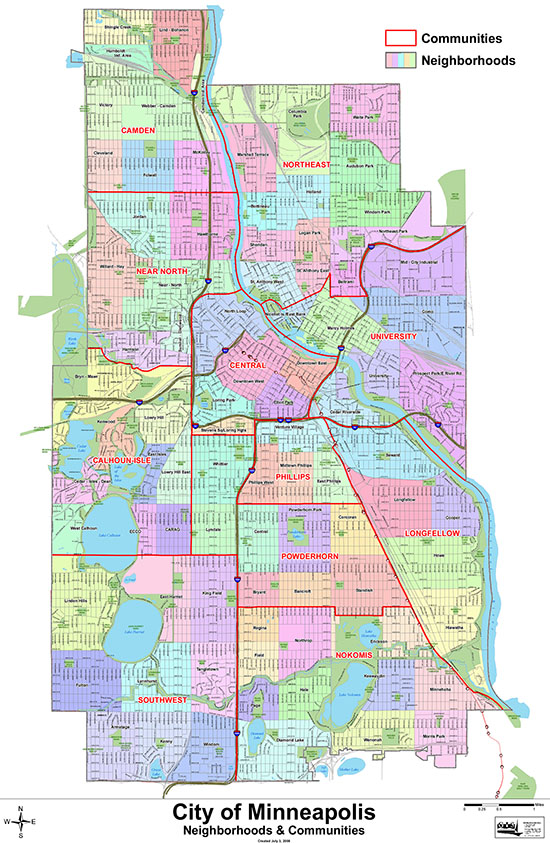

“This map shows Blackmoor Castle, the town, and immediate area. All those areas named in the first years of play are labeled. Some names were later changed by the players so that Troll Bridge became known as Mello’s Bridge … Also the East Gate became known as Gerri’s Gate (named after Gertrude the Dragon who was killed there by the Baddies.”

The impression I immediately take from this is that the city was highly responsive and could be radically transformed by the actions of the players. This is further confirmed in the next paragraph:

“Buildings 1, 5, 23, 40, Town Inn, Comeback Inn, and Merchant Warehouses are owned or lived in by Minions of the Merchant (run by Dan Nicholson, these quickly became the local Mafia and spread to several areas of the campaign). Buildings 13, 15, 20, 21, 24, 27, 35, 39 were those of the followers of the Great Svenny and the secret society set up by Mello the Hobbit and “Bill” (sort of a counter to the Merchant’s Mafia).”

The overall image is one of powerful, influential organizations being established by the PCs. This is awesome stuff and it really gets my blood pumping. It’s definitely something to keep an eye on for the future (in much the same way that kingdom-building sits atop the hexcrawl structure, this type of Great Society play would naturally sit atop a proper urbancrawl structure), but in terms of the urbancrawl structure itself it is, unfortunately, not terribly informative. Therefore, I’m going to lay Arneson aside (at least for the moment).