Yesterday I posted a scenario for Numenera called “The Last Precept of the Seventh Mask“. The scenario features multiple religious sects fighting for control of the body of the Seventh Mask (a religious leader denoted by the strange, mask-like biotech growth which extrudes from their face). The basic idea is that the PCs will approach the camp of one of these sects, get hired to protect them on their journey to the aldeia of Embered Peaks, and then be forced to deal with the other factions in an orgy of violence and collusion and zealotry.

But when I ran the scenario? That’s not what happened.

THE STARSCRIPT CAVERN

The PCs in this campaign have been traveling around inside the Narthex. You don’t need to know much about the Narthex except that it’s bigger on the inside than the outside and that it teleports semi-randomly around the landscape of the Ninth World. (If you want to basically think of it as a TARDIS that doesn’t travel through time and can’t leave the planet its currently on, you wouldn’t be too far wrong. Except this particular TARDIS is populated by a group of religious zealots that the PCs have inadvertently ended up being in charge of. But I digress.)

For this particular scenario the Narthex was going to appear at a location they couldn’t predict. It was important, therefore, for the local resident expert to look at the starscape above their arrival point to figure out where they had ended up. When they emerged from the Narthex, they found themselves inside a giant cavern with walls covered in ancient runes that glowed with a faint silver light. The starscript writing described the Narthex as a holy relic, but whoever had worshiped the Narthex here was long dead and gone.

As they emerged from the cavern, however, to gaze up at the stars above, they saw the lights of a camp further down the side of the mountain.

RAVAGE BEAR DELIGHT

The camp itself was tucked out of sight behind some tall outcroppings of rock, but they could hear the distant sounds of the people who were resting down there.

The idea here should be pretty obvious: I expected them to go down to the camp. There they would meet the Bensal kokutai and Fassare would ask for their help in guarding the body of the Seventh Mask on its journey to Embered Peaks.

But that’s not what happened.

Instead, they decided to simply keep quiet, take their star readings, and retreat back to the Narthex.

So I checked my notes. What would happen next?

Well, a pack of six ravage bears was supposed to attack the Bensal kokutai encampment that night. So they did. The PCs heard the roar of the ravage bears (and identified them) as they rushed the camp.

Once again, the intention should be obvious: I expected the PCs to rush down to help the unknown campers. They could drive off the ravage bears and–

Nope.

The PCs had suffered a previous encounter with a pair of ravage bears and their bodies still bore the scars to prove it. Six of them? No, thank you. They rolled up their star charts and ran back to the Narthex with the screams of the ravage bears’ victims echoing in their ears.

IN THE MORNING’S LIGHT

The next morning the PCs came back out of the Narthex and went down to investigate the camp. The ravage bears had… well, ravaged it. Tents were shredded. Dismembered limbs and half-devoured bodies were strewn about. It was clear that several more bodies had been dragged away from the site.

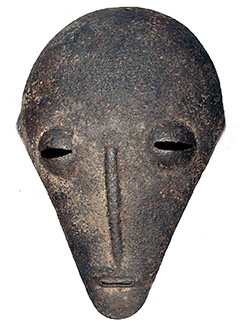

The only incongruous element was the bier of the Seventh Mask, which I decided had been left undisturbed by the ravage bears. Two of the PCs — Laevra and Sheera — were incredibly creeped out by this and the biotech, mask-like growth on the corpse’s face didn’t help matters much. While Laevra, the nano, examined the mask, another PC — Phyros, a clever jack who employs magnetism — decided it would be funny to program his morphable mask to look exactly like the biotech extrusion. Laevra and Sheera, for their part, were largely unamused.

Laevra eventually concluded that there was still living activity within the biotech of the mask. The group fell into a debate about whether or not they should cut it off the corpse: Laevra had curiosity on her side. Phyros, for all of his monkeying about with the morphable mask, was legitimately concerned that it might be infectious or dangerous.

While this debate continued, I decided to have a group of Caral kokutai show up on their flying platform. Since the Caral kokutai had been stalking the Bensal kokutai, this made sense. I also thought it might offer me an opportunity to re-hook the scenario: The Caral were just as interested in transporting the Seventh Mask to Embered Peaks. Like the Bensal kokutai, the Caral kokutai would also be concerned by the other factions in the area and could easily ask the PCs for help.

Of course, that’s not what happened.

APOTHEOITES

Remember that Phyros had made his morphable mask look just like the Seventh Mask?

Yeah.

As the energy platform of the Caral kokutai swept down into the grotto, their initial hostility towards finding the PCs standing in the midst of the carnage melted away into confusion as Phyros presented himself as the Eighth Mask. This story wasn’t completely plausible: Generally speaking, the Eighth Mask — as a reincarnation of the Seventh Mask — should have been no more than a babe. But with an extremely glib tongue, Phyros managed to sow enough confusion to convince the Caral kokutai scouts they should bring their leader, Moora, to him. (It helped that he was able to spin the gory deaths of the Bensal kokutai as being some sort of “righteous fury” directed upon heathen unbelievers.) Then, with a major effect on a final persuasion role, he convinced them that there were secret rites he needed to perform with the body of the Seventh Mask in secret. That meant that all of the Caral kokutai left, planning to return shortly with Moora.

So what were the “secret rites” that Phyros needed to perform?

Well, as it turned out, they entailed grabbing the body of the Seventh Mask and hightailing it back to the Narthex.

Entering the Narthex, it should be noted, means taking a liftshaft (i.e., elevator) down into a vast, extradimensional space. Exiting the liftshaft, you enter the Nave: A seemingly bottomless (and topless) shaft crisscrossed with gantries and catwalks.

As soon as the PCs reached the Nave in this particular case, they hauled the Seventh Mask’s corpse out of the lift, sliced the mask off its face (revealing a featureless face of fresh, baby-like flesh), pocketed the mask, and then dumped the corpse over the railing into the abyssal darkness below while resolving not to leave the Narthex again until it had jumped to a new location.

THE END

The best part? This is the third time that Phyros has ended up falsely presenting himself as a religious icon or deity. He’s not even doing it on purpose!

There are probably a lot of GMs who would look at this sequence of events as a failure of some sort. The PCs “wrecked the scenario”. My preparation was “ruined”.

But if you take a moment to look at how I actually prepped this scenario, you’ll note that I was never actually wedded to a particular outcome. Instead, as I described in Don’t Prep Plots, I created a kit with a number of tools:

- The starscript cavern

- The kokutai culture and their religious beliefs

- The corpse of the Seventh Mask

- The Bensal, Caral, and Gatha kokutai

- The chirogs

- The ravage bears

- The map of the local area

And while I would have liked to have gotten the Gatha kokutai and the chirogs involved, the reality is that most of those tools got used. Virtually none of them got used the way that I had expected, but the scenes that actually played out were really entertaining and insightful and memorable largely because they were unexpected. The table was filled with laughter and there were also some really meaningful questions asked about who they had become as individuals when they ran and left the Bensal to their fate.

Now, if I had invested a lot of time into carefully preparing schedules of ambushes for the road from the Bensal camp to Embered Peaks? Then I would have wasted a lot of time and had a lot of prep “ruined” by what happened. So I’m glad that I emphasized smart prep and trusted my instincts at the table to handle the rest.

face: A strange, mask-like biotech growth which extrudes into a faceless visage.

face: A strange, mask-like biotech growth which extrudes into a faceless visage.

prepping bangs can be a very flexible and effective way to prep. In

prepping bangs can be a very flexible and effective way to prep. In