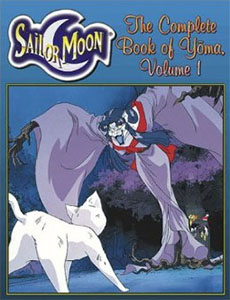

Tagline: A resource almost any GM of Sailor Moon should make every effort to get their hands on.

The Complete Book of Yoma: Volume 1 is the seventh Guardians of Order book I’ve reviewed for RPGNet (Big Eyes, Small Mouth; Big Robots, Cool Starships; The Sailor Moon Roleplaying Game and Resource Book; and the three Sailor Moon Character Diaries being the others). I continue to be impressed with their efforts, as the company steadily makes it way closer and closer to a hallowed inclusion on my “buy everything these guys do” list. The Complete Book of Yoma is a resource almost any GM of the Sailor Moon roleplaying game should make an effort to get their hands on.

The Complete Book of Yoma: Volume 1 is the seventh Guardians of Order book I’ve reviewed for RPGNet (Big Eyes, Small Mouth; Big Robots, Cool Starships; The Sailor Moon Roleplaying Game and Resource Book; and the three Sailor Moon Character Diaries being the others). I continue to be impressed with their efforts, as the company steadily makes it way closer and closer to a hallowed inclusion on my “buy everything these guys do” list. The Complete Book of Yoma is a resource almost any GM of the Sailor Moon roleplaying game should make an effort to get their hands on.

WHAT’S IN THIS BOOK?

The Complete Book of Yoma basically has four primary features (in my mind, anyway):

COLOR SECTION: Let’s start with the glitz and the flash: In the center of the book you’ll find an eight page, full-color section printed on glossy paper. This section, like the plentiful use of art throughout the rest of the book, illustrates (yet again) the huge advantage which Guardians of Order has here: After all, if you’ve got a couple hundred animation stills to choose from, you can (and they do) provide four or five pictures of every single monster in the book without a second thought … because you’re not stuck having to pay the artists.

YOMA: The core of the book, of course, are the yoma themselves. I discuss these in a bit more detail below. (For those of you wondering, at this point, what the hell a “yoma” is, the answer can be found there.)

HOW TO USE YOMA: The first section of the book deals with how to handle the yoma in your campaign. A solid resource, it succinctly sums up the basic foundation on which these creatures exist – summarizing the standard formulas of the television show (and how to break them to make a better roleplaying campaign); who controls yoma and how; where yoma come from; general cosmology… the whole nine yards. The best part of this section, in my opinion, are the charts which statistically break down the yoma – by who controls them, what attacks destroyed them on the TV series, their type, and their gender.

RANDOM YOMA: This is actually a part of the first section of the book, but I’m spinning it off into its own section because I really liked it. Basically, Lindsey Ginou realizes that the yoma can be broadly classified in various ways (for example, there are the yoma who “charm people”). Thus you can, effectively, chart these – and once you’ve got the charts you might as well throw in some probability tables and get yourself some randomized yoma. The resulting charts can be used to actually randomly generate a yoma – or you can use the charts as a quick reference for designing your own basic yoma packages.

THE YOMA

Anyone with even a minimal amount of exposure to Sailor Moon will know that the basic structure of any given episode is simple: Sailor Moon and the Sailor Scouts face down a nasty magical creature. They are nearly defeated, but in the end they find the yoma’s weakness and defeat it. There’s also an arc structure to each season of the show (for example, during the entire course of the first season the Sailor Scouts are facing off against Queen Beryl.

So what’s a yoma? “Yoma” translates, roughly, in to English as “monster”. The Complete Book of Yoma: Volume 1 assembles and presents every single monster which the Sailor Scouts face down during the first two seasons of the show. (This includes the Cardians and the Droids, who are not, strictly speaking, yoma. But that’s just a technical distinction, and not all that important.)

Each yoma is given a full page description, and are arranged in the order they appear in the television series (thus the yoma from episode one appears first; the yoma from episode two appears second; and so forth).

Each yoma is described with: Their English and Japanese names, the name of the episode(s) they appeared in (English, Japanese, and translated Japanese), their type (defined in the introductory material), their master (who sent them), who defeated them in the show, and their final fate on the show.

Additionally, more lengthy passages are given describing their physical appearance, the significant events of their appearance(s), various points of interest, and (of course) their actual stats.

In case you missed it: With this information you (of course) get a standard monster manual entry for every yoma, but you also get a strategy section on how they can be defeated, and also adventure hooks on how to design a story around them.

A great deal of care has gone into constructing the yoma so that they behave exactly as they do in the television series. Using the rules of the Sailor Moon roleplaying game and the stats as they are provided, you can recreate the events of the television series exactly as they appeared on the screen. Guaranteed. Nothing is more frustrating than picking up a licensed RPG only to discover that you can’t create characters who can do the same things the characters the license is based on. No such problem here.

CONCLUSION

Having read this book, I really can’t imagine running a Sailor Moon campaign without it. At the end of the day it does precisely what every supplement should do: It helps you run the game, without being absolutely necessary.

In other words: Sure, you can run Sailor Moon without owning this book. There is absolutely nothing here that you cannot create yourself using the core rulebook. But The Complete Book of Yoma makes you ask a simple question:

Why would you want to?

And that’s why you should buy it.

Style: 4

Substance: 4

Author: Lindsey Ginou

Company/Publisher: Guardians of Order

Cost: $17.95

Page Count: 90

ISBN: 1-894525-00-0

Originally Posted: 2000/04/06

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.