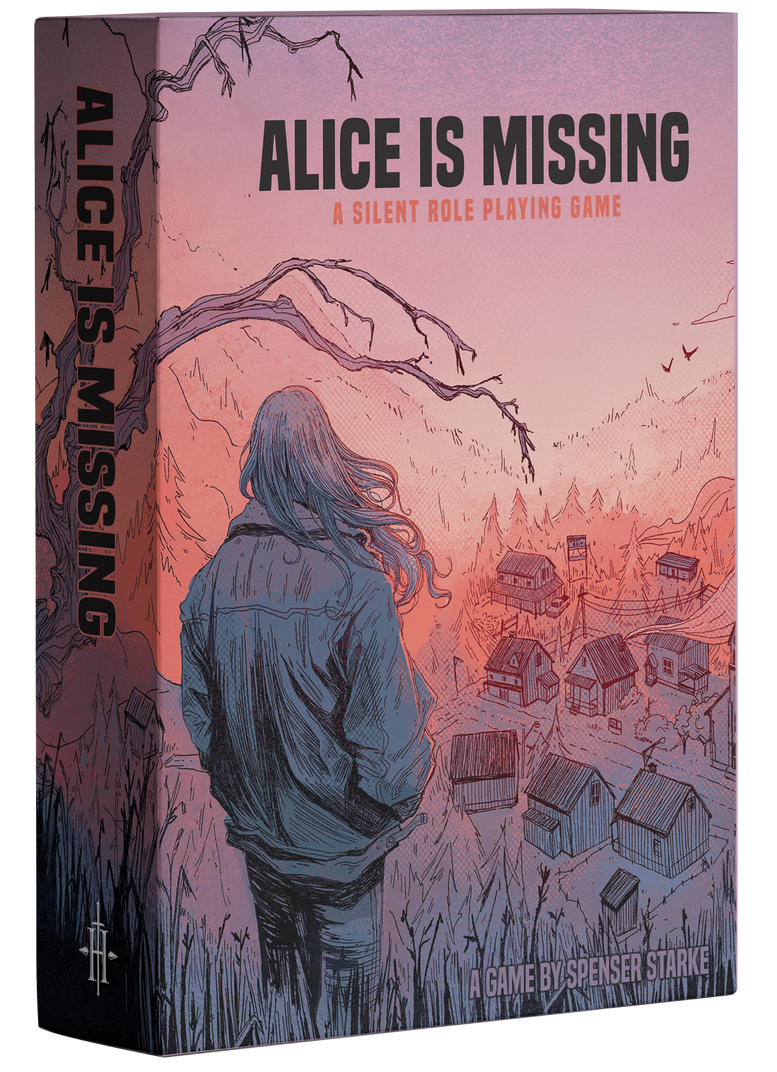

Alice is Missing is a stunningly beautiful storytelling game that delivers an utterly unique and unforgettable experience. I’ve played it twice, with different groups, and each game was profound. Every player was deeply affected, and several texted the group the next morning to say that they’d dreamed about the events of the game.

The premise of Alice is Missing is in the title: A high school student named Alice has gone missing, and the players will take on the roles of her friends as they try to figure out what happened while dealing with the emotional trauma of her disappearance.

The central conceit of the game is this: You don’t talk. Instead, all of your interactions — all of your roleplaying — takes place via text messaging.

HOW IT WORKS

You can play with three to five players and you’ll start by each selecting one of the five broad, archetypal characters provided. These are quickly fleshed out with Drives, which provide Motives (a key personality trait) and two Relationships, which you’ll assign to two different player characters. It’s a fairly quick process that creates a remarkably broad dynamic of play while keeping the structure of play focused.

Now the Facilitator will start a group text message with all participants by sending a text with their character name in it. All the other players reply by sending their character name, at which point everyone should create a contact for that number (if they don’t have one already) and change its name to the character’s name.

At this point play begins: The Facilitator will open an Alice is Missing video which provides both a soundtrack and a 90-minute timer. From this point forward, no one speaks: The Facilitator will send a message initiating the game, and then everyone will spend the next hour and a half texting.

The core mechanic of the game revolves around Clue cards. These are synced to the timer — so, for example, there’s an 80 minute clue card, a 70 minute clue card, and so forth. There are three different cards for each time interval, and these can be freely intermixed, resulting in thousands of potential game states.

Each Clue card contains a prompt for the player who draws it:

- Reveal a Suspect card. This person shows up at your door acting suspicious. What weird question about Alice do they keep asking you?

- Reveal a Location card. You dig up some weird or unexpected history about this location. What do you learn about this place that would make it the perfect spot to hide?

The player creates the answer to this question and introduces it into the group chat, pushing the narrative of the game forward.

As you can see from these examples, the game also includes Suspect cards and Location cards. These help shape the mystery of Alice’s disappearance, and a number of clever mechanics are used to make sure that the narrative in the back half of the game evolves logically and naturally from the foundation laid down in the first half of the game, even as it’s ultimately being guided by the player’s creativity.

Finally, the game provides a deck of Searching cards which are more flexible: Whenever a PC decides to go somewhere without being prompted by a Clue card, they should draw a card from the Searching deck to reveal what they discover there. (Examples include “a drop of blood in the fresh snow” and “a loaded firearm.”)

SOME GRIT IN THE GEARS

Overall, Alice is Missing does an excellent job of walking a new player through the rules. The rulebook is actually split into two parts: The first is an in-depth explanation of the rules, and the second is a Facilitator’s Guide which walks the Facilitator (most likely the game’s owner) through the exact steps they should take to explain the rules to the other players (including short scripts they should read at every step).

This is crucial to the game’s success, because if everyone at the table isn’t completely onboard with the rules, the central conceit of silent gameplay won’t work and the game will fall apart. Spenser Starke, the designer, deserves major kudos not just for a great game, but for making sure the presentation of the game was everything it needed to be.

With that being said, there are a few places where grit gets into the gears, and I’m going to point them out so that when you play Alice is Missing you can hopefully benefit from my experience and avoid them.

First, the game comes in a lovely box that suggests completeness. Unfortunately, the box is missing components. There are no character sheets, for example, and there’s also supposed to be a stack of missing person posters that isn’t in the box. These are all easily downloadable from the publisher’s website (at least for now), but these aren’t just optional supplements: The rulebook will tell you to, for example, select a missing person poster, and you won’t be able to. (So make sure you track these down ahead of time and print them out.)

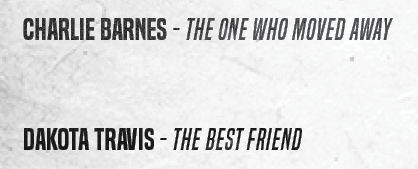

Speaking of the character sheets, they’re too small. For example:

In the half-inch by three-inch space between “Charlie Barnes” and “Dakota Travis,”you’re supposed to write down their physical description, favorite class, home life, etc. plus the answer to their Background question plus more… You can’t do it. The character sheet should have been designed as a full-page sheet and probably also double-sided to work properly.

After everyone picks their characters, they’re encouraged to specify their character’s pronouns. This is great in principle, but Alice is Missing completely flubs the execution by constantly referring to the characters by predetermined pronouns (and even baking this into the mechanics). Points for trying, but beaucoup negative points for failing. (A close edit of the rulebook to remove predetermined pronouns and, most especially, removing gendered identities from the character roles would be the minimum required to fix this. Ideally, I’d also want all the character names to be gender neutral.)

On a similar note, every character has a Secret. These are listed on the character cards, and so when the Facilitator is instructed to lay the character cards out in front of the players and have them select which characters they want to play, all of the players are going to read every single character’s Secret. The Facilitator’s script then almost immediately says, “Do not share your Secret — it should come out in play.”

This is not actually a problem: The players are not their characters, and what the rulebook means is that the answer to your Secret prompt question should not be included in your character introduction, but instead revealed during play. But every single group I’ve played this with has immediately gone, “Wait. Did we screw up? I read the Secrets!” It’s a very minor thing, but it’s a consistent irritation and it’s probably worth thinking about how you want to tweak that particular point of presentation to sidestep it.

My final critique of Alice is Missing is more significant: The rulebook sets things up so that the Facilitator is always playing the character of Charlie Barnes.

I can understand why they’ve done this. (It allows them to script specific examples into the scripts in the Facilitator’s Guide.) But it makes for a really bad experience if you’re the one who owns the game and is, therefore, always the Facilitator introducing new players to it. Fortunately, it’s pretty easy to fix this and let the Facilitator play any of the characters. (But it will require some edits to the guide and its procedures.)

WHAT MAKES IT BRILLIANT

I took the time to highlight all these little minor bits of grit in the gears of Alice is Missing because you’ll want to know about them when you play the game.

And you will want to play this game.

Because it’s brilliant.

The mechanics are elegant, easily grasped, and expertly tuned by Starke to effortlessly guide almost any group to a powerful story which is nevertheless unique every time. It’s a true exemplar of storytelling game design.

The novelty of the experience certainly helps to make it memorable, but the true brilliance of Alice is Missing is more than that. It’s a game that effortlessly immerses you in your character: The experience of play — focused through your text messaging app — is seamlessly identical to the character’s own experience.

You know how the world can sometimes sort of drop away when you get focused on your phone? Starke leverages that fugue state — everything else drops away, and the only thing you’re truly experiencing is the world of the text messages. A world where you’re not talking to your friends; you’re talking to Charlie and Dakota and Julia. (This is why it’s so important to change your contact names before playing.)

In addition, the text-based medium automatically leads the player to create the game world through a creative closure which is nigh-indistinguishable from the closure you perform every day in the real world. When Julia, for example, texts you to say, “There’s someone outside my window!” you immediately imagine that scene in exactly the same way you would if one of your actual friends texted that to you.

The power of that in a roleplaying experience really can’t be underestimated.

Either of these two things — the near-flawless mechanical design or the novel genius of the text-based roleplaying — would make the game worth checking out.

The two together?

Alice is Missing is one of the best storytelling games ever made.

Grade: A+

Designer: Spenser Starke

Publisher: Hunters Entertainment / Renegade Game Studios

Cost: $21.99

Page Count: 48

Card Count: 72