Go to Part 1

It is surprisingly easy to mess up the resolution of group actions. (In no small part because so many games include group resolution mechanics that are flawed. Or don’t offer a group resolution mechanic at all.)

The primary problem is skewed probabilities. The classic example of this is a group of five PCs trying to sneak past a guard. The GM looks at the standard mechanics for this sort of thing and, with logic seemingly on their side, has each PC make a Stealth test.

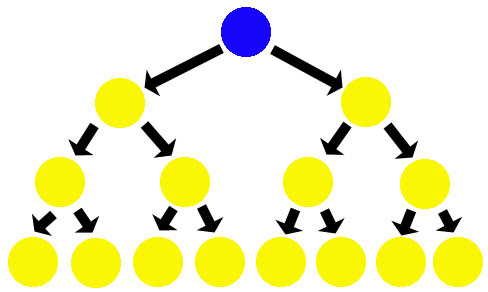

Say that these PCs are pretty good at stealth, so they each have a 70% chance of passing the test. “Since they’re all pretty good at this,” the GM thinks, “they’ll have a pretty good chance of sneaking past this guy.” But, in reality, they don’t. Because the failure of any single character is a de facto failure for the entire group, they now only have a 17% chance of successfully sneaking past the guard.

This categorical error happens because our brains do not intuitively grasp probabilities. So we set up a stack of “pretty good odds” and fail to realize that, collectively, a string of uninterrupted successes is still incredibly unlikely to happen.

This gets even worse if five PCs are trying to sneak past a group of five NPCs. In 3rd Edition D&D, for example, this effectively becomes a check in which the PCs are rolling 5d20 and keeping the lowest result while the NPCs are rolling 5d20 and keeping the highest result. The average roll of 5d20-keep-lowest is 3. The average of 5d20-keep-highest is 17. That 14 point differential means that it’s virtually impossible for a party of characters to sneak past a group of evenly matched opponents.

(The odds are actually even worse than that in 3rd Edition, because virtually all stealth attempts will require both a Move Silently and a Hide check.)

The argument can certainly be made that this is realistic in some sense: A large group should have a tougher time sneaking past a sentry than one guy and more eyes means more people who can spot you. But I would argue that the probability skew is large enough that it creates results which are both unrealistic and undesirable.

In the case of stealth, for example, the effects of the skew are obvious: Since it’s virtually impossible for them to succeed, group stealth attempts quickly drop out of the game. When stealth is called for, it takes the form of a sole scout pushing out ahead of the rest of the group. And when the scout becomes too fragile to survive when the check finally fails, stealth stops being a part of the game altogether.

THE FOUR TYPES OF GROUP ACTION

When dealing with a group action, the first thing a GM must determine is what type of group action they’re dealing with. In general, I find this breaks down into four categories:

(a) Everybody is performing individually and succeeds or fails individually.

(b) Everyone is attempting the same task, but as long as one of them succeeds it’ll be fine.

(c) Everyone is working together to accomplish a single action collectively.

(d) Everyone is working together / assisting each other, but everyone still needs to accomplish the action (i.e. succeed).

Consider a Climb check, for example:

- Everyone starts climbing the wall independently.

- Bob tries to climb up and grab the idol. Then Nancy does. (Or maybe they’re both trying at the same time, but as long as one of them gets the idol, the idol has been gotten.)

- People lower a rope and help pull someone up. (Limited by the number of additional people you think pulling on the rope will meaningfully help.)

- Everyone is belayed together and assisting each other in scaling the mountain.

Or a Stealth check:

- Each person tries to sneak past a guard one at a time.

- Everyone simultaneously tries to infiltrate the room with The Button in it from radically different directions, so that even if one of them gets discovered (i.e. fails the check) the others are unaffected by it. (This is somewhat contrived, but I can’t actually think of a non-contrived example of a Stealth check where members of the group can fail as long as one member succeeds.)

- Steve distracts the guard by showing him a nudie mag while Gwen sneaks past him.

- Aragorn leads the hobbits through the dark wood, working to keep the whole group concealed from the roving Nazgul.

TYPE 1: SIMULTANEOUS INDIVIDUAL ACTION

Everybody is performing individually and succeeds or fails individually.

The first type is not, in fact, a group action. It is many simultaneously individual actions which, although they are identical to each other, are each seeking to accomplish a separate goal.

When resolving “group” actions of this type, use the normal process you use for resolving individual actions.

Here’s a relatively clear cut example: The group needs to make six porcelain dishes. There are six PCs, so each of them makes a Craft check in order to make a single porcelain dish. If they all succeed, then each of them has separately created a porcelain dish and, as a result, they have created a total of six porcelain dishes.

Despite these types of actions not actually being a group action at all, this is the form of group action resolution that most GMs seem to default to. I think this is a combination of most systems (notably those most GMs start out with) not featuring any explicit mechanics for other types of group actions, and the fact that it’s also frequently the easiest resolution method. (It’s really easy to simply say, “Everybody give me an Athletics test.” And it’s also really easy to use the resolution mechanics for individual actions because those are, generally speaking, the simplest mechanics and the default mechanics in any roleplaying game.)

Basically my whole point here is that rather than defaulting to this form of resolution, I think most GMs would benefit from thinking of this as the last resort when it comes to resolving group actions. In other words, make sure that it’s not a group action before defaulting back to simultaneous-individual resolution.

But if you’re looking for a general rule of thumb on when it’s “okay” to use Type 1 resolution, look at any situation where the failure of one character doesn’t cause the other characters to ALSO fail. Thus, it’s okay for everyone to climb up a wall separately, because one character falling behind the rest doesn’t mean that those who succeed are automatically held back. (Although the consequences may nonetheless be dire.)

TYPE 2: INDEPENDENT GROUP EFFORT

Everyone is attempting the same task, but only one of them needs to succeed.

Use this type of group action when the characters are all aimed at accomplishing a single goal, but are each acting completely separately in their efforts to achieve that goal.

When resolving an independent group effort, you’ll actually still use the normal process for resolving individual actions. But as long as at least one of the individual actions succeeds, the attempt is successful.

You can also think of this as “best result counts”.

To use our previous example: The group needs one porcelain dish. Each of the six PCs makes a Craft check in order to make a single porcelain dish. As long as at least one of them succeeds on the check (i.e., makes a dish), the group will have the one dish that they need. If the quality of the dish matters, the dish they’ll use will be the best one they made (i.e., the one with the highest check result).

The disadvantage of this method is that it actually causes probability to skew in the other direction. It’s the situation you end up with where everybody in the group says, “I search the hall for traps” (either simultaneously or sequentially), greatly increasing their odds of success.

Once again, it can be argued that this probability skew is realistic. (More eyes on a problem makes it more likely that someone will spot the solution.) And I, personally, tend to have much less of a problem with this sort of skew because (a) success rarely causes the gameplay experience to flatten (due to dropped strategies) and (b) I think it’s actually very difficult for a GM to err too much on the side of the PCs succeeding.

However, when it’s necessary or desired, this skew can be counteracted by having consequences — or the risk of consequences — for participating. This often takes the form of something bad happening on a failed check; or on a failed check with a sufficiently bad margin of success. (Are you sure you want to search the hall when a poor check means potentially triggered a trap? The materials for making a porcelain dish are expensive, so does it make sense to have Sally — who’s terrible at the Craft check — participate in the group pottery session?)

One thing to consider is the possibility for a sufficiently large margin of success by one character participating in the independent group effort to negate (or ameliorate) the consequences of failure for another member of the group. (For example, Elyssa fails her Search test by 5, but Raasti succeeds on his by 10, so he reaches over and snatches her back mere moments before she bumbles into the tripwire.)

TYPE 3: COLLABORATIVE ACTION

Everyone is working together to accomplish a single action.

For example, when multiple characters are working together to fix a car. Or build a gravity gun. Or research an obscure topic at Miskatonic University.

The distinction here is that there is one thing the group is attempting to achieve, and they are all contributing to that single attempt. Mechanically speaking, there are a couple of broadly applicable approaches.

Assistance: One character is “taking point” on the attempt. (This is generally whoever the most skilled character is at whatever the primary task is, but not necessarily depending on circumstance.) The other characters who are assisting the point man grant a bonus to the point man’s test. This assistance may require a successful skill test in its own right, which may or may not be the same skill test that the point man is making (and may or may not be made at the same difficulty).

The form of this bonus can vary. 3rd Edition D&D, for example, hard codes this as the Aid Another action and grants a +2 bonus. In a dice pool system you might grant the point man a bonus die. The Cypher System has several different bonuses depending on the relative skill levels of the characters involved and the type of help being given.

Collective Margin of Success: An alternative method is to look at the total margin of success generated by the entire group and compare that against a target number. (This is very common in dice pool systems where you count successes, since it’s just as easy to count successes from multiple sources as it is to count them from a single source.) This approach can be quicker (since all of the skill tests can be resolved simultaneously), and can also be particularly appropriate in scenarios where there’s no convenient “point man”. The disadvantage is that the target numbers from these collaborative actions tend to be out of sync with the target numbers for individual actions, which lacks elegance and can cause some headaches when it comes to consistency.

With either approach, there may be practical limits on how many characters can simultaneously assist in a specific attempt. (You can only squeeze so many people under the hood of a hotrod.)

TYPE 4: PIGGYBACKING

Everyone is assisting each other in a task where all need to simultaneously succeed.

The distinction between Type 4 and Type 1 can be something of a gray area: Everyone climbing a wall separately is clearly a Type 1. But if the team is working together, employing belaying techniques, and the like, at what point does it become Type 4?

In my opinion, when in doubt, default to Type 4. I don’t always do a great job of this myself, but for all the reasons discussed above I think it’s the better way to go.

In my opinion, when in doubt, default to Type 4. I don’t always do a great job of this myself, but for all the reasons discussed above I think it’s the better way to go.

Basic Version: One character takes point on the attempt and everyone else “piggybacks” on their success or failure. (If they succeed, everyone succeeds. If they fail, everyone fails.)

In GUMSHOE, the point character suffers a penalty based on the number of characters that are piggybacking. However, piggybacking characters can spend a single point from a skill pool (usually, but not always, the same skill pool as the point character’s test) to negate their penalty.

When I adapted piggybacking to the D20 system, the piggybacking characters needed to succeed on a skill test at one-half the normal DC of the test. The point character could reduce the DC of the piggybacking test for their allies by increasing the difficulty of their own test.

Simple Variant: Have every character participating make a skill test. If at least half of the group succeeds, the entire group succeeds.

Complex Variant: Everyone who succeeds on the test grants a bonus to those who would have otherwise failed. If the collective bonus from those succeeding is enough to bump all the failures up to successes, the attempt succeeds.

FINAL THOUGHTS

I’ve jotted down several different options for resolving the various group actions. For any system you’re running, however, you generally only need one for each type of group action. In some cases, of course, the system itself may come prepackaged with a mechanic for doing that. If you find yourself needing to add a mechanical structure for one of the types, you should hopefully find it relatively easy to take one of the options presented and find a way to use it in the system you’re using.

Practical experience has taught me that, generally speaking, the GM should make the determination of whether or not a group check is appropriate and what mechanic should be used for resolving it. For example, when I first introduced piggybacking mechanics into my D&D games, I left it up to the players to determine whether or not a particular attempt at Stealth would be a “normal check” or a “piggybacking check”. The problem was that players fairly consistently went with the default method of resolution, and they would also consistently rebel the minute the point character failed their test and would want to default back to individual tests.

So I recommend that, in practice, you treat group checks just like any other ruling: Determine how the action should be resolved and declare that to the PCs.

“Okay, this will be a piggyback check. Who’s taking point?”

In my opinion, when in doubt, default to Type 4. I don’t always do a great job of this myself, but for all the reasons discussed above I think it’s the better way to go.

In my opinion, when in doubt, default to Type 4. I don’t always do a great job of this myself, but for all the reasons discussed above I think it’s the better way to go.