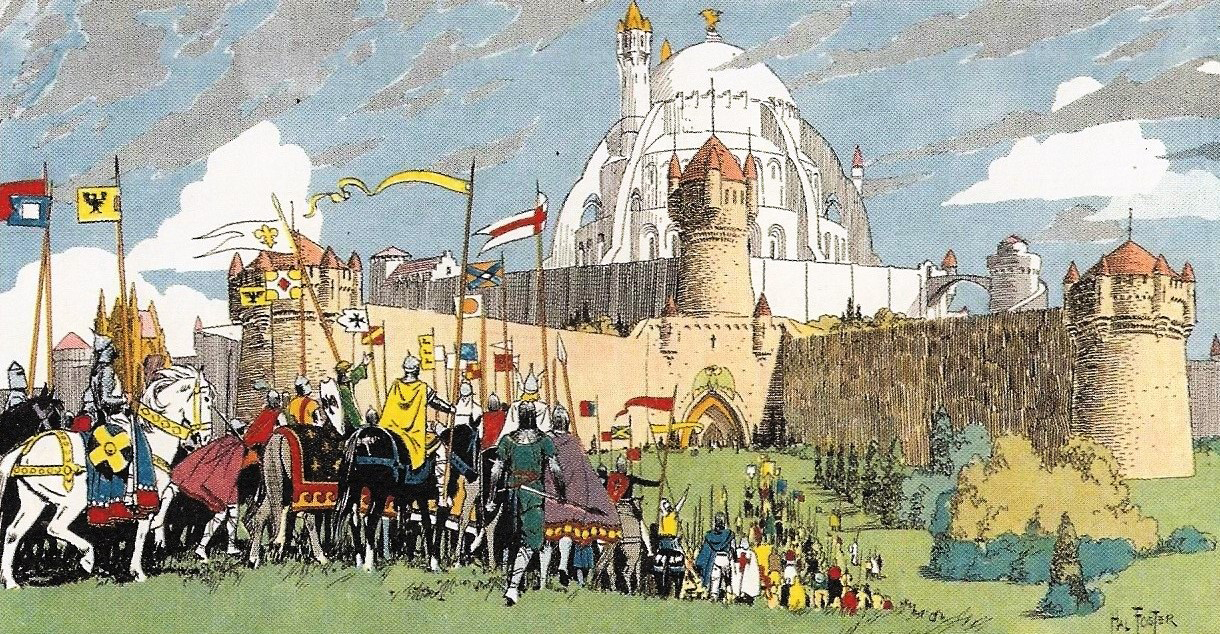

Hal Foster’s groundbreaking Prince Valiant was adapted into the first “storytelling game” by Greg Stafford back in the ’80s. Many of you likely grew up with its much diminished legacy in the Sunday comic strips of your youth, but Foster’s original strips (as you can see below) was a beautiful, atmospheric, mythic-real take on the Arthurian legend. Stafford’s game sought to capture this universe with an elegant ruleset and incredibly simple character creation mechanics, and it’s recently been republished by Nocturnal Media.

The game is divided into two parts. The Basic Game, although the first to bear the title of “storytelling game”, is very much a traditional RPG. What made it particularly innovative at the time, however, was that it eschewed simulation-focused complexity and instead stripped things down to a simple, narrative-focused mechanic.

In the Advanced Game, Stafford introduces a structure by which players can, in mid-session, become Storytellers, running the group through short episodes before returning control of the session to the Chief Storyteller. Meta-currency rewards are given in exchange for taking on these GMing duties, creating not only one of the first STGs but also an early troupe-style game.

Thirty years later, Prince Valiant is no longer innovative. (Quite the opposite: The industry has been following its lead and looting its corpse.) But it remains an elegant and accessible game that, although its parts have been parceled out, still provides a unique playing experience that’s not really been duplicated anywhere else.

This is actually a great time to get into Prince Valiant: In addition to Nocturnal Media reprinting the RPG, Fantagraphcs has been publishing a freshly remastered reprint series of Foster’s original comic. This new edition has been scanned from the original syndicate proofs, restoring Foster’s stunningly beautiful art and subtle storytelling.

Inspired by both, I’m currently laying down a bunch of material for bringing Prince Valiant to my gaming table. This includes assembling one of my system cheat sheets for the game. For those unfamiliar with these cheat sheets, they seek to summarize all of the rules for the game — from basic action resolution to advanced options. It’s a great way to get a grip on a new system and, of course, it makes it easier to introduce the game to new players and run the system as a Game Master.

WHAT’S NOT INCLUDED

These cheat sheets are not designed to be a quick start packet: They’re designed to be a comprehensive reference for someone who has read the rulebook and will probably prove woefully inadequate if you try to learn the game from them. (On the other hand, they can definitely assist experienced players who are teaching the game to new players.)

The cheat sheets also don’t include what I refer to as “character option chunks” (for reasons discussed here). In other words, you won’t find the rules for character creation here.

HOW I USE THEM

I generally keep a copy of my system cheat sheets behind my GM screen for quick reference and I also place a half dozen copies in the center of the table for the players to grab as needed. The information included is meant to be as comprehensive as possible; although rulebooks are also available, my goal is to minimize the amount of time people spend referencing the rulebook: Prince Valiant is one of those games which freely mix rules with philosophical discussions of how the rules can be used to best effect. The cheat sheets can’t duplicate that utility, but instead seek to pull the rules out for easy reference.

The organization of information onto each page of the cheat sheet should, hopefully, be fairly intuitive.

Page 1: Core Mechanics & Combat. Most of the game is right here.

Page 2: Skills. I went with slightly longer skill descriptions than I usually do for these cheat sheets because we found that the divisions between skills were finely defined (which makes sense given the relatively narrow focus of the game on knights and courtly life) and also not completely intuitive (because Stafford has, very cleverly, adopted a medieval understanding of philosophy in the division of knowledge and skill).

Page 3: All the Modifiers. All of them.

Page 4: Special Effects & Fame. I’ve tried to appropriately emphasize the degree to which the Fame Award values are very much median guidelines that it’s expected the GM will vary from. (Review the appropriate sections of the rulebook as necessary.)

Page 5: Advanced Storytelling. I initially played with the idea of putting all of the Advanced rules on a single sheet, but ultimately decided that I was likely to include Advanced Skills (and character creation) even in campaigns that didn’t use all of the Advanced Storytelling rules. (Partly due to the exigencies of the new open table format I’m experimenting with using Prince Valiant as its foundation.)

MAKING A GM SCREEN

As with my other cheat sheets, the Prince Valiant sheets can also be used in conjunction with a modular, landscape-oriented GM screen (like the ones you can buy here or here).

If you have the modular four panel screen, like I do, then this is quite simple: The “Advanced Storytelling” sheet is a nice reference, but you don’t need to be able to access its information in a single glance. So you can just insert the other four sheets and you’re good to go.

PLAY PRINCE VALIANT!