Go to Part 1

The creative and evolving process of restocking a megadungeon is something I discuss at length in (Re-)Running the Megadungeon. I’m not going to rehash that material here, and if you’re unfamiliar with that earlier essay you might want to take a few minutes to peruse it.

As I’ve mentioned in the past, I find that the process of restocking a dungeon is as much art as science: You want to look at the context of how events are evolving within the dungeon — the actions the PCs have taken, the responses NPCs have to those actions, and so forth — in order to determine how the dungeon will evolve over time.

With that being said, I often find it rewarding to incorporate random procedural content generation. It can prompt me to pursue unusual creative directions and force me out of my comfort zone. It can also “force” me to put in the work when it can sometimes be easier to default to “nothing happens”. For example, at the beginning of every session in my OD&D Thracian Hexcrawl I would check every dungeon lair that had been previously cleared out by the PCs with a 1 in 8 chance that it had been repopulated. This “forced” me to revisit areas that I might otherwise have left fallow.

For Castle Blackmoor I could have easily just used my standard procedures for megadungeons: A kind of instinctual “feel” for each section of the dungeon, combined with on-demand procedural content generation checks or creative inspiration for restocking each section. (I, personally, draw a distinction between game mechanics and procedural content generators: Although they can be superficially similar, I think their function in the game is quite different. One way that this manifests in my campaigns is that I consider mechanical results binding; they can’t — and shouldn’t! — be fudged. Procedural content generators, on the other hand, exist to prompt creativity and, because they’re not mechanics, they’re not mechanically binding. But I digress.) Since my design goals for Castle Blackmoor were explicitly about exploring an alternative to my typical megadungeon procedures, however, I thought it made sense to take a closer look at the restocking methods I would use with the dungeon.

As far as I know, however, Arneson never explained his restocking procedures. (If he even had a formal procedure.) So there’s nothing explicit for us to base our restocking techniques on. What we can do, however, is look at how a restocking procedure could be created to capitalize on the tools provided by the Arnesonian procedures we’re using.

Here are three approaches that I developed.

EMPTY ROOMS METHOD

The first option would be to simply rerun the original stocking procedure between sessions: Check each empty room to see if it now contains an encounter. If so, generate the encounter.

The problem with this method, even if it is limited only to the room that the PCs passed through during the previous session, is that it will, statistically speaking, usually lead to the generation of more creatures than the PCs are eliminating. The dungeon will slowly turn into an overcrowded tenement.

GLENDOWER TEMPLATE METHOD

An alternative would be to use your original dungeon key as a Glendower template during restocking: Check each empty room which has a protection point budget to see if it has been reinhabited. If it has, respend the original protection point budget and check to see if the room has treasure.

This method has the advantage of simplicity. It also eliminates bookkeeping during the session: You don’t need to keep track of exactly which areas the PCs have “tapped” in their explorations, you can simply check the key after the fact to see which areas have been depopulated.

A potential disadvantage of this method is that it can result in the dungeon becoming predictable: The same rooms will always be where monsters live, and the other rooms will never be filled.

Under the logic that your Glendower template was designed to present an interesting tactical challenge regardless of how its budget is “filled”, however, this might actually be viewed as a feature. Any predictability of the dungeon will also be undercut by your wandering monster checks. It’s not like there will be any place in the dungeon where the PCs will be “safe”; it’s more like there are certain areas of the dungeon which make for good lairs, and those are the areas that monsters keep moving back into.

QUADRANT CHECKS

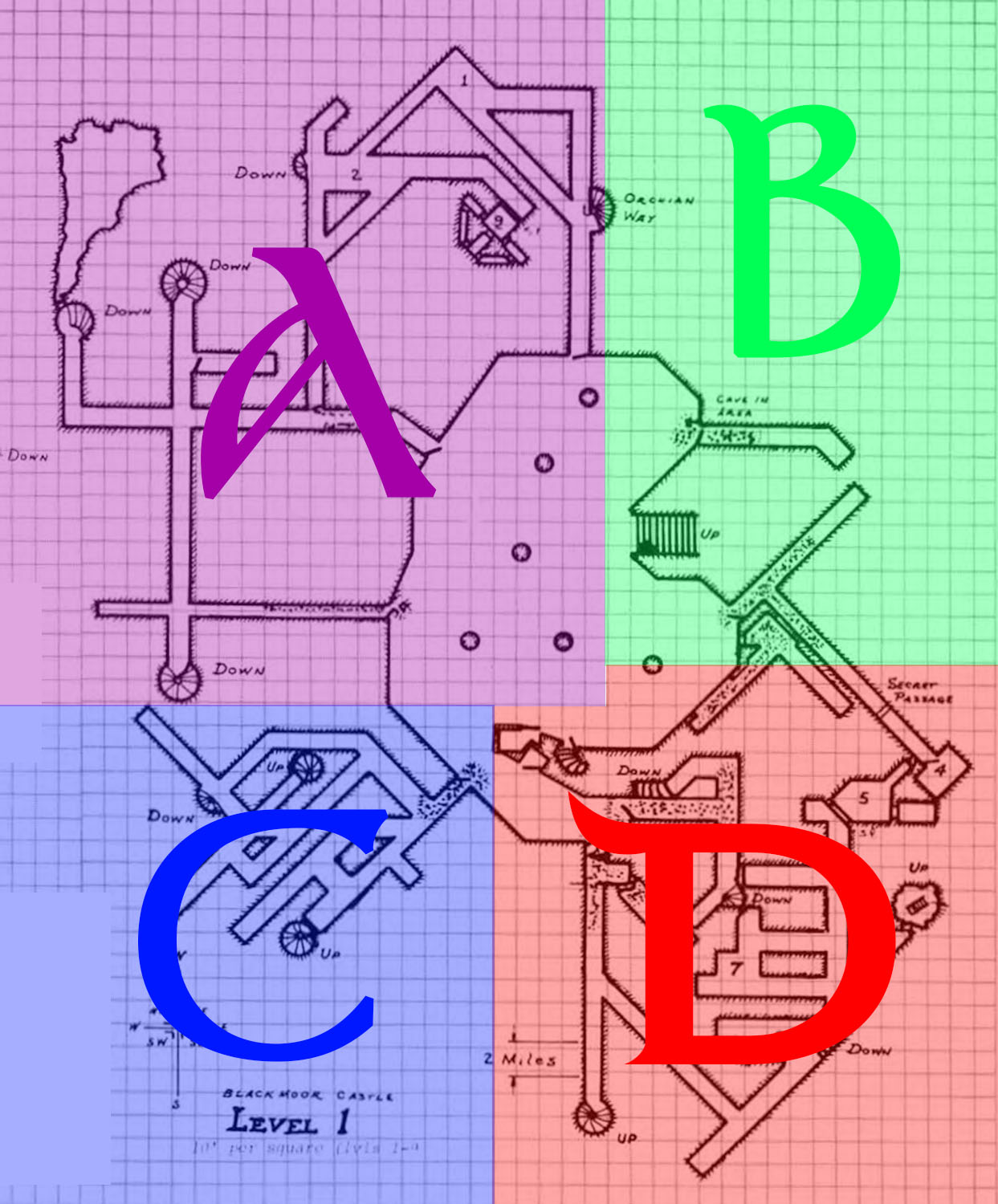

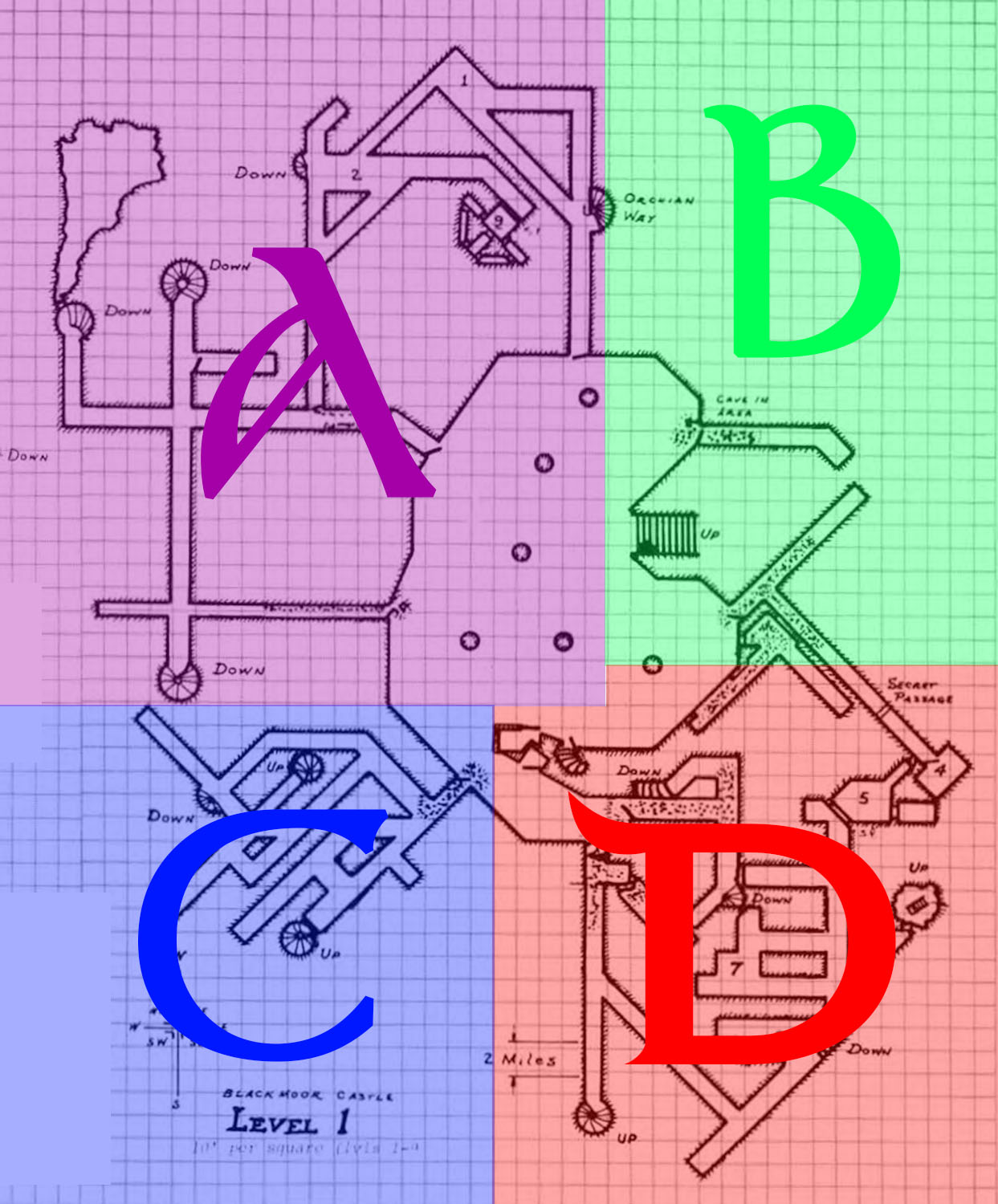

When Arneson adapted the Blackmoor dungeons for convention play in the late ’70s, he instituted a quadrant-based system of wandering monsters: He divided the map for each dungeon level into a quadrant and pregenerated a random encounter for that quadrant. (“Players rolling a wandering monster in Quadrant A will have encountered Sir Fang!”) It’s an effective system for pushing specific, prepackaged content into play in a convention setting, but it’s not a system I was particularly interested in exploring.

For the purposes of restocking, though, this concept of “dungeon quadrants” interests me. It can be somewhat crude, but it also mirrors my own “sector” understanding of a dungeon complex. (These are the Tombs, this is Columned Row, these are the Worg training facilities, this set of rooms ‘belongs’ together, as does this one over here, etc.) If you wanted more detail, you could block out specific sectors. Quadrants, however, give you a simple one-size-fits-all approach that can be quickly slapped down onto any level of the dungeon.

You’ll still want to use common sense, of course: In the map above, for example, you can see how I’ve tweaked the borders of each quadrant on Level 1 to follow natural divisions in the dungeon corridors.

Here’s the procedure I’ll be experimenting with:

- For each quadrant that the PCs entered during the previous session, there is a 1 in 6 chance that it will be restocked.

- For each restocked quadrant, check each uninhabited room (using the normal stocking procedures) to see if it is now inhabited.

- Check ALL rooms in the quadrant for treasure, although rooms that were currently inhabited only have a 1 in 20 chance of generating new treasure.

Note that this procedure can add new encounters even to areas that the PCs haven’t previously depleted. This is intentional, and a likely explanation would be creatures reinforcing their ranks in response to the armed thugs rampaging around their homes.

It’s quite possible that, after a little playtesting, you may want to tweak the odds listed here. As I write this, I haven’t actually had much chance to put these into practice yet. (I suspect 1 in 8 for the quadrant test might be a better fit. And the 1 in 20 chance for adding treasure to currently inhabited areas might be too low, but I’d rather be conservative with the money spigot.)

Next: Special Interest Experience