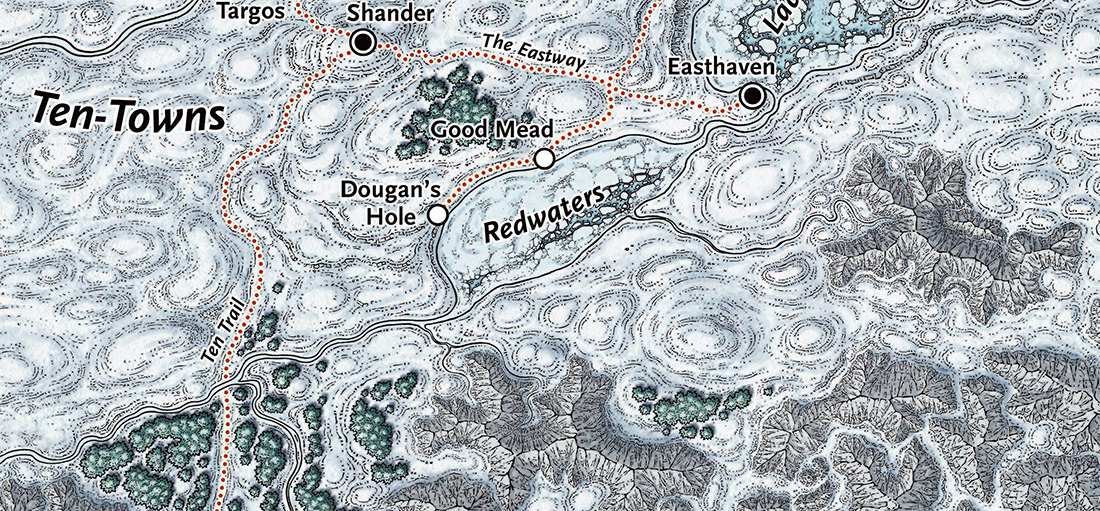

Auril the Frostmaiden has claimed Icewind Dale, laying her enchantment upon it: a terrible curse of perpetual winter. The denizens of Ten-Towns – ten settlements clustered around the lakes at the center of the Dale, nestled between the Spine of the World and the Great Glacier – grow increasingly desperate for a spring which never comes. When the PCs arrive in this gloom-riven land, they will discover that the cold of the wintry north has leeched into the hearts of men. Surrounded by darkness, can they be the flame that rekindles the light of hope?

As the campaign begins, the players are presented with an open world sandbox: They’re largely free to wander through Ten-Towns as they please, helping people and engaging with crises that present themselves in each of the settlements. A bonafide sandbox is unusual (if not unique) among official D&D campaigns, and the town-based structure used by Icewind Dale is intriguing and ripe with possibility.

Unfortunately, like several of the other official D&D campaigns I’ve seen, Rime of the Frostmaiden only flirts with being something innovative and unique before abruptly ripping off its mask and shouting, “Aha! Just kidding! I was a railroad the whole time!”

In this case, at least, the sandbox is at least fairly legitimate for as long as it lasts. But after just four or five levels, the whole thing abruptly collapses down into the linear plot. (Which is, itself, beset with problems.)

With that being said, Icewind Dale: Rime of the Frostmaiden is bursting with a ton of cool stuff. The covers are metaphorically strained with a bevy of good sandbox material, a handful of epic set-pieces, stunning artwork, and fifty pages of chilling new monsters (plus a thematic miscellanea of other useful elements). Before we go any further, I’m just going to say that I like it. The book is not without its shortcomings (we’ll get to those), but I liked it enough that I felt comfortable launching a campaign in the Icewind Dale sandbox without first making major alterations to the material. Which is, for me, fairly high praise indeed.

THE SANDBOX

One of the primary problems with Rime of the Frostmaiden is how poorly it explains its structure. This is particularly true of the sandbox, the explanation of which is both inadequate and filled with vague contradictions that further complicate comprehension. But this is, more or less, how it works:

There are two starting quests. An easy-to-miss feature here is that these quests are tonally distinct from each other — one is tracking a serial killer that ties into the darkness that has seeped into Icewind Dale; the other is a hunt for fanciful fairy creatures called chwingas. Both, however, thematically tie into the over-arching campaign: The Frostmaiden is a dark and feyish goddess, and the two starting quests reflect that from different angles. (The DM can also use this to dial in the tone they want for the campaign, by choosing or emphasizing one quest over the other.)

In any case, these starting quests are designed as light framing devices that will motivate the PCs to move from one town to another. Each town has an additional quest keyed to it and opportunities to pick up rumors about quests in other towns. So as the PCs journey around, they will collect additional quests and most likely begin doing those while continuing to work towards accomplishing their original quests.

The starting quests thus effectively provide a default action for the beginning of the campaign: If the players have any doubt about what they should be doing next, they can simply go to a new town and look for their starting quest item (the serial killer or the chwinga).

Once the PCs have accomplished a certain number of quests, they level up and effectively “unlock” an additional rumor table (which the book confusingly refers to as “tall tales,” despite the fact that they are completely reliable sources of information) that will begin pointing the PCs towards what I’m going to call the Chapter 2 quests (because that’s where they’re described in the book). These quests are, obviously, more difficult; they also tend to take the PCs further out into the wilderness around Ten-Towns.

Now, there are some caveats here.

First, Rime of the Frostmaiden instructs the DM to only use one of the starting quests. This can be an option for aesthetic reasons, but objectively speaking it’s almost certainly wrong: The structural function of the starting quests, as noted, is to provide a default action that will move the PCs through several towns. Both of the quests, however, can end essentially at random (i.e., the players choose the correct town, find the thing they’re looking for, and the quest ends). You want both quests on the table to provide redundancy. Having both quests in play will also deepen the default interaction with each community (because they need to look for multiple things).

Most importantly, however, giving the PCs two different quests to simultaneously pursue at the start of the campaign will immediately break the players of the expectation that they’re going to be doing a linear set of assigned tasks.

Most importantly, however, giving the PCs two different quests to simultaneously pursue at the start of the campaign will immediately break the players of the expectation that they’re going to be doing a linear set of assigned tasks.

The second caveat is that the way Icewind Dale handles rumors is mostly wrong. The advice in the book for using the rumor tables is radically inconsistent, and there are simply too many places where the DM is told to spoonfeed rumors to the PCs one at a time. This is more or less the exact opposite of what you should actually be doing.

See, in a sandbox campaign you want LOTS of rumors to be in play at any time. The essence of a sandbox campaign is that the players have the ability to choose or define what their next scenario is going to be. In order for that to work, the PCs need to be in an information-rich environment and rumors are, broadly speaking, how you accomplish that. If you spoonfeed them the rumors (i.e., scenario hooks) one at a time, you’re choking the life out of your sandbox. (See Juggling Scenario Hooks in a Sandbox for a longer discussion of this in detail.)

To be fair, there are other sections of the book that correctly tell you to be profligate with the rumors. But even some of this advice can go awry. For example, there’s one passage where it suggests that the GM should just randomly give players rumors out of the blue. (“Lo! From the heavens I give unto you… a rumor!”) The reality is that the acquisition of rumors should flow from the actions taken by the PCs.

(Which is also why the investigative action taken in each town related to the starting quests should, generally speaking, explicitly trigger the local rumor table.)

These are regrettable shortcomings in the book (particularly if one imagines it being used by a neophyte GM), but not seriously debilitating as you can, for the most part, simply ignore the bad instructions on how to use the material.

The third caveat, however, deals with the actual adventure material itself. While many of the sandbox adventures presented in Icewind Dale are well done, there are too many that miss the mark. (And some badly so.)

For example, consider the starting quest in which the PCs need to track down a serial killer named Sephek. The scenario hook for this quest is one of the worst I’ve ever read. It’s comically bad.

Hlin has taken it upon herself to investigate the recent murders because no one else – not even the Council of Speakers – can be bothered. Hlin is studying the characters closely, trying to decide if they’re worth her time. Ultimately, she takes the chance and draws them into conversation, asking them to help her take down her only suspect: a man named Sephek Kaltro. Here’s what she knows about Sephek and the victims:

“Sephek Kaltro works for a small traveling merchant company called Torg’s, owned and operated by a shady dwarf named Torrga Icevein. In other words, Sephek gets around. He’s charming. Makes friends easily. He’s also Torrga’s bodyguard, so I’m guessing he’s good with a blade.

“His victims come from the only three towns that sacrifice people to the Frostmaiden on nights of the new moon. This is what passes for civilized behavior in Icewind Dale. Maybe the victims found a way to keep their names out of the drawings and Sephek found out they were cheating, so he killed them. Maybe, just maybe, Sephek is doing the Frostmaiden’s work.

“I followed Torg’s for a tenday as it moved from town to town. Quite the devious little enterprise, but that’s not my concern. What struck me is how comfortable Sephek Kaltro looked in this weather. No coat, no scarf, no gloves. It was like the cold couldn’t touch him. Kiss of the Frostmaiden, indeed.

“I will pay you a hundred gold pieces to apprehend Sephek Kaltro, ascertain his guilt, and deal with him, preferably without involving the authorities. When the job is done, return to me to collect your money.”

“Hello. Yes. I would like to pay you 100 gold pieces to kill this random person because he’s a serial killer… Well. Maybe. Who knows, really? I have no actual evidence he’s a killer. Hell, I don’t even know if he was actually in the same towns where the killings happened. But maybe.. just maybe, the killer is working for the Frostmaiden. Or maybe not. But if the killer IS working for the Frostmaiden, then MAYBE he would be immune to the cold. And this guy doesn’t wear a coat. So… yeah. Definitely the killer.”

That’s pretty dumb. But then it gets worse:

Quest-Giver: I followed Torg’s caravan for ten days.

PCs: So where is it now?

Quest-Giver: No idea.

The quest-giver followed the caravan for ten days, became convinced someone in the caravan was the killer, and then… left and went to a completely different town? So they could sit in a tavern and stare at strangers until randomly deciding which ones they would ask to go kill someone on their laughable say-so?

The crazy thing is that the quest-giver is completely right: The Frostmaiden is sending Sephek to kill people who bribe officials to take their names off the lottery list.

But… only three of the Ten-Towns even do the human sacrifice thing. If the Frostmaiden wants to kill people for not being available as sacrifices, why isn’t Sephek targeting the OTHER seven towns?

There are a number of similar head-scratchers strewn about Rime of the Frostmaiden, but there’s also a fair number of scenarios that are just badly designed.

For example, in the town of Bremen there’s some sort of murderous creature in the lake that’s attacking the local fishing boats. The PCs are supposed to grab a boat, head out onto the lake, and deal with the creature. (It’s an awakened plesiosaurus.) Here’s how the scenario works:

- Get in the boat.

- Roll on a random table of events until the plesiosaurus shows up.

The structure itself is obviously lackluster, but it’s made worse because (a) none of the results on the table are actually interesting and (b) they simply repeat until you roll the magic numbers on the d20 that end the misery.

Here are the actual rolls I made while simulating how this scenario would play out:

- Knucklehead trout hits you in the head.

- Knucklehead trout hits you in the head.

- Knucklehead trout hits you in the head.

- Nothing happens.

- Targos fishing boat shows up, then leaves.

- Nothing happens.

- Nothing happens.

- Nothing happens.

- Targos fishing boat shows up, then leaves.

- Plesiosaurus shows up.

It’s here! Finally!

… but then there’s a 1 in 3 chance that it just leaves before the PCs can interact with it! Which is, in fact, what I rolled. So then:

- Nothing happens.

- Knucklehead trout hits you in the head.

- Nothing happens.

- Nothing happens.

- Plesiosaurus comes back!

(It should be noted that each of these checks takes an hour, so the party also presumably went back to town and slept somewhere in there.)

Imagine running this at the table!

And yes, obviously, any DM worth their salt isn’t going to actually do this. But that just raises the question of why it was written this way in the first place, doesn’t it?

And then there’s Tali, the quest-giver. They’re a raging asshole.

Before the quest they say: “Can you go out on the lake and take notes on a dangerous beast that’s killing people?”

Then after the quest they say: “Oh! You’re back? In payment, here’s a potion that makes dangerous beasts friendly so that they won’t kill you.”

(I acknowledge that the potion wouldn’t work because the plesiosaurus has been awakened, but THEY don’t know that.)

To be clear, there are many quests that don’t have problems like this. (The book has more than twenty of these sandbox quests.) But there are, frankly, too many that do — like the dwarves who offer to pay the PCs more to retrieve a shipment of iron than the iron is worth; or the bad guys who captured a castle so they could live there and immediately dumped corpses into the water supply; or the one where all the NPCs are baffled about how they can find the bad guys, so they take the PCs to the tracks that the bad guys left in the snow and scratch their heads until one of the PCs says, “Maybe we could… follow the tracks?”

Speaking of tracks, it turns out that A LOT of the quest hooks in Icewind Dale are based around following tracks. Fail the Wisdom (Survival) check to follow the tracks? Guess you fail the quest! Sucks to be you! (And it’s frequently worse than this because the designers are actively sabotaging the already fragile structure. For example, there’s one quest where the PCs can fail to successfully follow the required tracks because they did so at the wrong time of day. And another where they follow the tracks of some thieves half way to their goal, but then the tracks automatically blow away in the wind, forcing the PCs to make blind Wisdom (Survival) checks to search the hills for… well, they don’t actually know WHAT they’re looking for, but if they find anything it will DEFINITELY be where the thieves are, right?) This is sort of okay in a sandbox like Rime of the Frostmaiden because you don’t need to succeed at every quest, but it’s still not great scenario design… particularly if you’re doing it over and over and over again.

Most of the material that’s compromised like this is, ultimately, salvageable. But you will need to put in the work to salvage it.

TRANSITION TO LINEAR

Let’s talk about the dragon in the room.

There comes a point in the campaign where the PCs have tracked down Sunblight, the duergar fortress in the mountains at the southern end of the Dale. As they approach the fortress, the chardalyn dragon that the duergar have been constructing out of magical, evil crystals flies out of the top of the fortress and begins winging towards Ten-Towns.

This is an incredibly epic, awesome moment.

It is also the point where the Icewind Dale sandbox begins collapsing into a linear scenario. This is, in my opinion, a bad decision. It seems to kick in at exactly the moment where, in my experience, the most interesting emergent gameplay in a sandbox will start appearing. In other words, stuff is just going to start getting awesome when the campaign abruptly says, “Eh. Fuck it. Let’s do something else.”

But beyond that, it’s just poorly done.

The intention is that the PCs have a choice: They can finish climbing up to Sunblight and assault the fortress OR they can climb down the mountain and race back to Ten-Towns to save it from the dragon.

Except the choice doesn’t actually work because the PCs have no way of understanding the stakes: It’s extremely unlikely that they’ll know what the dragon is going to do. “Dragon flying away from fortress” doesn’t auto-translate to “it’s going to destroy Ten-Towns.” I’d argue it’s far easier to read that as a signal to “hit the fortress fast before it gets back.” So there’s an opportunity for a cool choice here, but it’s a missed one.

But let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that the players do understand the choice: There’s a dragon flying to Ten-Towns and they have to catch it!

… except they can’t. It turns out the choice to chase it or not is irrelevant. If you use the travel times listed for the PCs and the dragon in the book, the decision to raid Sunblight is incredibly unlikely to have any impact on the outcome in Ten-Towns. And, in fact, the overwhelmingly likely outcome in Ten-Towns is that all ten towns will be destroyed except for Bryn Shander and maybe Targos. (Despite this, the book gives no guidance at all for what the post-apocalyptic Ten-Towns is going to look like.)

So the choice doesn’t work. But whether the PCs assault Sunblight first or not (and we’ll come back to Sunblight in a moment), when they come back down the mountain they find a woman waiting for them with enough dog sleds for all of them. She wants them to help her do a job and she offers them a lift back to Ten-Towns.

First: This entire setup is just inherently awkward in its execution. The players decide to head back to town and an NPC pops up in the middle of the wilderness to say, “Hey! Need a lift?”

It’s just silly.

Second: The entire back half of the book absolutely requires that the PCs hitch a lift and work with this NPC. (The book tells you this explicitly multiple times. As far as I can tell, it’s not wrong.) This is an incredibly weak structure to hang an entire campaign on!

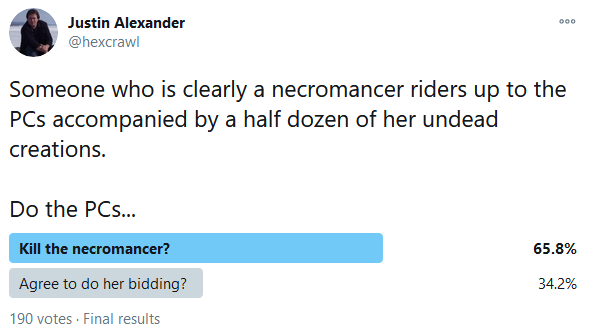

But it’s actually worse than that, because this NPC is clearly a necromancer: She’s got undead minions hanging out with her and everything. That’s a problem, because I think it’s overwhelmingly likely that the PCs are going to kill her without a second thought.

I was interested to see what other people thought of this, so I ran a poll on Twitter. 190 people voted on the most likely action the PCs would take, and two-thirds said she was toast… along with the rest of the campaign.

It doesn’t help that even if the PCs do talk to her, she makes it clear in her pitch that she’s a member of the Arcane Brotherhood… who have been repeatedly established in the first half of the campaign as unrepentant bad guys who betray everyone who works for them.

And, again, the PCs have to agree to work with the necromancer ex machina or the rest of the campaign can’t happen. Here’s how that works:

- The necromancer gives the PCs a ride back to Ten-Towns.

- After they deal with the chardalyn dragon, she tells them that she has a cool job for them, but they’re going to have to level up first.

- Once the PCs have leveled up, she leads them to Auril’s Abode, where they have to steal a lorebook.

- The lorebook has a spell which will let them access the lost city of Ythryn.

- The necromancer leads them to the location of Ythryn and casts the spell.

In short, once the PCs choose to go to Sunblight they trigger a sharp transition from the sandbox to a linear sequence of set pieces:

- Destruction’s Light (chasing the chardalyn dragon, which we’ve already discussed)

- Sunblight Fortress

- Auril’s Abode

- The Lost City of Ythryn

For the rest of this review, we’ll be looking at each of these set-pieces in detail.