TURN BACK THE CLOCK

Turn Back the Clock by Kyle Tam is a thinly disguised roman a clef of Arthur C. Clarke’s and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001. The PCs receive a distress call sent from a ship thought lost for centuries: Mankind’s first expedition to Jupiter. It’s been knocked loose in time by the presence of the Star Child Flux Child. The original crew is experiencing Annihilation-like transformations, and if the PCs aren’t careful, they’ll similarly become lost in space and time.

Conceptually this seems really interesting. Unfortunately, it’s the execution that kills this one.

First, imagine adapting 2001: A Space Odyssey, but you aren’t really sure how to do that, so the structure of your adventure is just punching the Flux Child in the head until it’s “felled,” freeing you from the ship. But, also, that’s basically impossible because the Flux Child does 5d100 damage, has 20 maximum Wounds, and you forgot to include a Health score.

Second, I frequently found the text confusing. For example, “the crew is not technically in danger,” but they were currently fusing with the furniture and/or have pieces of their bodies falling off, plus they will shortly cease to be sentient. Hmm. I feel like I have a radically definition of “danger” than the author here.

Finally, there are more fundamental design problems here. For example, a core structure of the adventure is, “The longer you spend onboard the Charon, the more of yourself you lose. Each day, make a Sanity save or else roll on the [Distortion Table].” But the adventure is keyed as a pointcrawl with three briefly described areas.

This is a problem I frequently see in published adventures. I’ve discussed a similar problem in Running Background Adventures: There’s simply not enough narrative material to fill the time necessary to trigger this structure.

“Clarke’s Star Child does body horror” is a cool concept. But, sadly, there’s nothing on the page in Turn Back the Clock that I would actually use in bringing that concept to the table. This is a disappointing miss for me.

GRADE: F

The PCs are hired to pick up a secretive shipment from an automated shuttle. The only problem? An experimental combat drone – the Synthetic Predator 1st Design, 3rd Revision (or SP-1D3R) – has stowed away on the shuttle to escape the facility where it was being tested. Desperate for energy, it begins draining the power systems on the PCs’ ship.

This is another good concept with shaky execution.

Designer Nikolaj Gedionsen describes the adventure as “a claustrophobic game of cat-and-mouse aboard a failing ship where an intelligent machine predator turns the crew’s familiar home against them.” Which sounds great, but immediately runs face-first into a ship map that’s entirely linear. It’s hard to play cat-and-mouse on a balance beam.

The Plea also frequently relies on overriding or ignoring the core rules of Mothership. In my experience, this sort of thing doesn’t work because the players get frustrated at the bullshit “threat” that’s being arbitrarily thrust upon them.

The adventure includes its own mechanical superstructure in the form of a Power Drain system (modeling and tracking the SP-1D3R taking over and depleting the ship’s systems), but I have a difficult time believing it was ever playtested. The core of the system boils down to:

- Start with 12 Power.

- -1 Power when the drone connects to a system.

- If the PCs power down a section, it can’t be Power Drained and also save 1 Power per turn.

The math just fundamentally doesn’t math here. Nonetheless, I’ve done several dry runs of the system using various interpretations of what it might have meant (did you mean -1 Power per turn? can the drone be attached to multiple systems simultaneously?) and it just doesn’t work.

All of these issues, I think, explains why a significant chunk of this adventure is a section called “The Vibe.” Ultimately, that’s a pretty good summary of The Plea: It’s a concept running almost entirely on vibes.

GRADE: D

TESSERACT

Pyry Qvick’s Tesseract initially threw me for a loop because (a) it’s called Tesseract (a cube extended into fourth-dimensional space in the same that a square is extended to become a cube in three-dimensional space) and (b) it features a bunch of non-Euclidean cube-shaped rooms. So my brain kept trying to make the adventure work as an actual tesseract… but it isn’t.

Which is OK. I mention this only in the hope it might help you avoid the same pitfall and get straight to appreciating just how cool this adventure is.

Which is OK. I mention this only in the hope it might help you avoid the same pitfall and get straight to appreciating just how cool this adventure is.

Things kick off in Tesseract like this:

Your ship passes a massive metallic cube. After a moment, your ship passes by a massive metallic cube. Again and again. Your navigation shows no progress made.

On the cube’s surface, a hatch opens.

Crawling inside the cube, you discover a dozen of the aforementioned cube-shaped rooms, all arranged on a map that makes it easy for you to run as the GM, but devilishly complex for the players to unravel. (If they ever do.)

The rooms themselves are consistently themed, but each one is varied and intriguing. In addition to the navigational puzzle of the non-Euclidean map, exploring the cube is also deeply satisfying because the rooms present an interconnected mystery that allows the players to slowly piece together what’s happening here (and, hopefully, undo it). This is very much the adventure that Turn Black the Clock wanted to be, but dropped the ball on.

Season to taste with the creepy cube-droids which infest the place.

The net result is a creepy, well-designed adventure I am sure will leave your players disoriented, paranoid, and thrilled.

GRADE: B-

Rather than the trifold modules we’ve been reviewing, Dead Weight by Norgad is a twelve-page micro-adventure.

The PCs are crewing a cargo ship when an alien artifact in one of the ship’s holds activates, causing all dead bodies in the area to rapidly accelerate towards. It starts with all the meat in the ship’s galley, which rips through the crew currently eating dinner. The dead bodies of the crew, of course, are added to the mass of meat and bone, which rip through the hull of the ship, causing lockdown and atmospheric pressure doors to trigger throughout the ship.

As the investigation and emergency repairs begin, a crew member mortally injured in the initial incident dies, inflicting more damage… and that’s when corpses start arriving from outside the ship. Can the PCs figure out what’s going on and jettison the artifact before the asteroid the artifact was taken from arrives and annihilates the ship?

The concept of Dead Weight is elegant in its horrific simplicity. The execution is simply beautiful.

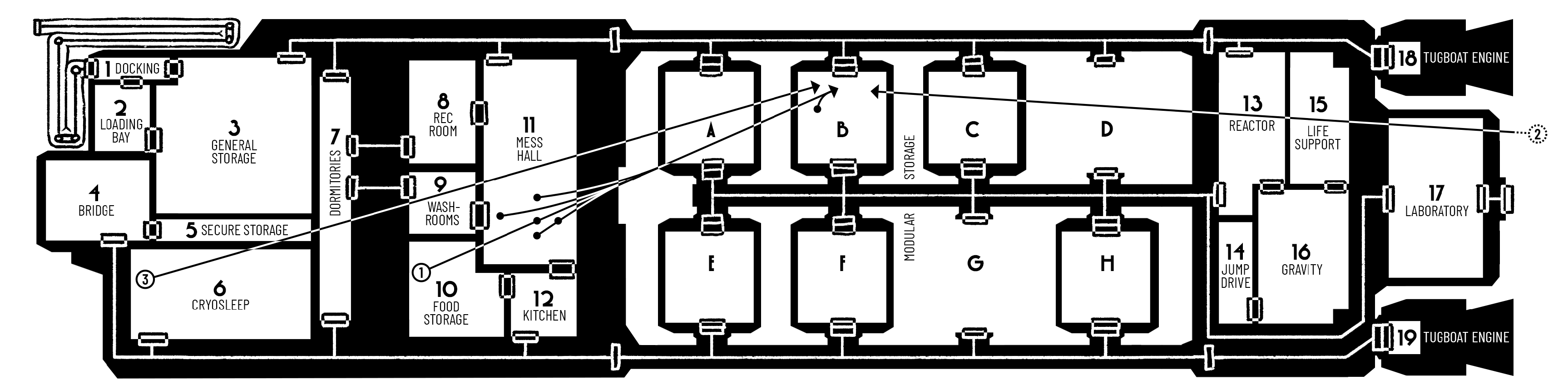

Just look at this map:

Each of the vectors here show the trajectory of damage from the scripted meat projectiles, and you can see how simple it would be to draw your own vectors and immediately understand the resulting damage as events play out at the table. This map is simply fantastic as both a reference and a structure of play, and Norgad has also included player handouts (without the GM-only info) that you can print out for the players.

The ship key itself is equally polished: Nested descriptions make it easy to master the adventure, while creating satisfying layers of investigation for the PCs. Clearly delineated post-incident shifts in the room descriptions make it a breeze to keep the potentially complicated continuity and dynamic environments of the adventure crystal clear in play.

I have only one quibble with the whole package: It’s not immediately apparent why the adventure track ends with the asteroid 98-Gobstopper crashing into the ships. Careful reading suggests that the asteroid – composed of “banded layers of oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, carbon, calcium, and phosphorus, with some other trace elements” – is actually the compacted remains of the countless dead attracted by the artifact at the asteroid’s core. But it would have been friendlier to the GM to just spell that out.

This quibble, of course, scarcely detracts from the whole package. Dead Weight went straight into my open table rotation. I adore it.

Note: When you run your own session of Dead Weight, I recommend taking the time to frame up and play through more of the back story that sets up the First Projectile incident. These events are well detailed in the text of the module, but I think it will work better if the players actually experience those events for themselves and then see the payoff.

GRADE: B+

Your review of Tesseract is entirely positive, why only a B- then?

Presumably because it isn’t actually a tesseract.

Yeah, and your glowing review of Dead Weight only earned a B+. What does it take to get an A?

Mostly I think it’s important to normalize the idea that something can be Good (or even Very Good) without being Excellent (A) or the One of the Best Things to Ever Exist (A+).

Check out the Guide to Grades.

Broadly, I’ve found it’s fairly difficult for trifold adventures or one-page dungeons to get A grades. This isn’t like a conscious choice on my part, but I think it’s quite difficult for such a short adventure to deliver the value I’d associate with an A or A+ experience.

As a teacher, I’m all in favor of avoiding grade inflation.

Also: naming your spaceship after the ferryman of the dead seems like a really bad idea. Almost as bad as naming it the Icarus.