I’ve been thinking about jump travel in Mothership. Here’s a quick summary, as described in the core rulebooks:

- Jump points are rated from Jump-1 to Jump-9.

- Utilizing a jump point requires a jump drive of equal to higher rating.

- For the crew of the ship, the jump always takes 2d10 days.

- Jumps usually seem to take the same amount of time for the rest of the universe, but each jump carries the risk of an unusual time dilation: Ships might disappear for months or even years instead of days.

- The longer/higher rated the jump, the more dangerous and severe the time dilation appears to be. It’s possible that some of the Jump-9 deep space exploration vehicles that have gone missing will reappear a thousand years in the future.

The rulebooks, however, leave these time dilation effects up to the GM’s discretion. I thought it might be useful to instead resolve the mechanically.

TIME DILATION

When a ship performs a jump, roll 1d10 per Jump rating (e.g., if a ship is making a Jump-3, roll 3d10).

For each 1 rolled on a d10, the actual trip duration increases by one step:

- days

- weeks

- months

- years

- decades

- centuries

If you’re making a standard Jump-1, you have a minimal risk of the trip taking 2d10 weeks instead of 2d10 days. If you attempt a Jump-3, on the other hand, there is a 1-in-1000 risk that you’ll roll three 1’s and return 2d10 years later.

Note: This does not change the subjective time experienced by the ship. For the crew, a jump trip seems to take 2d10 days, regardless of how much time passes in the wider universe.

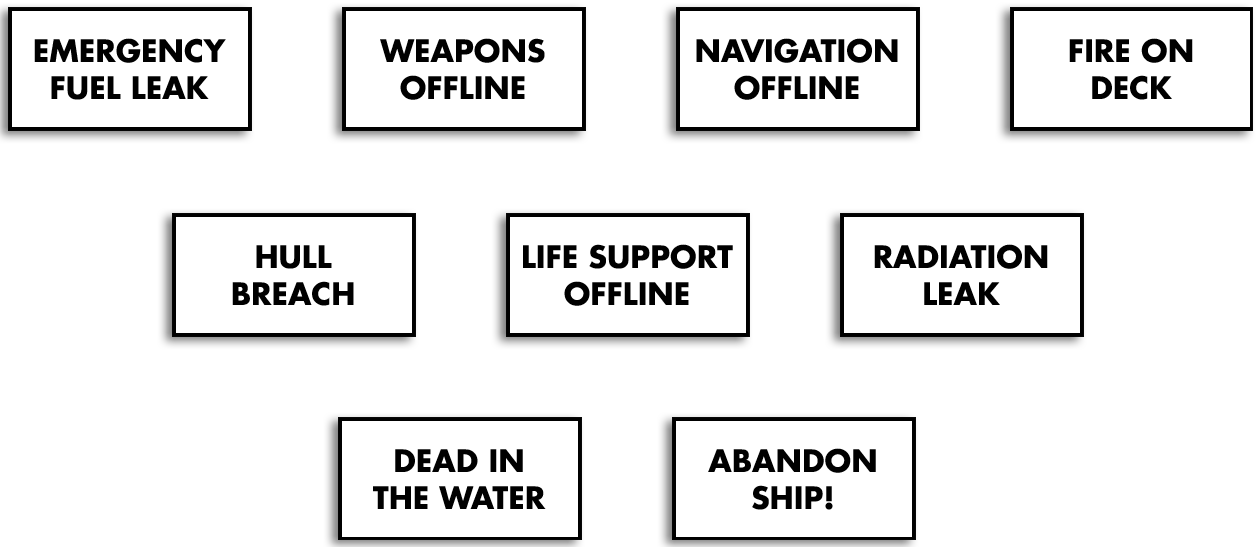

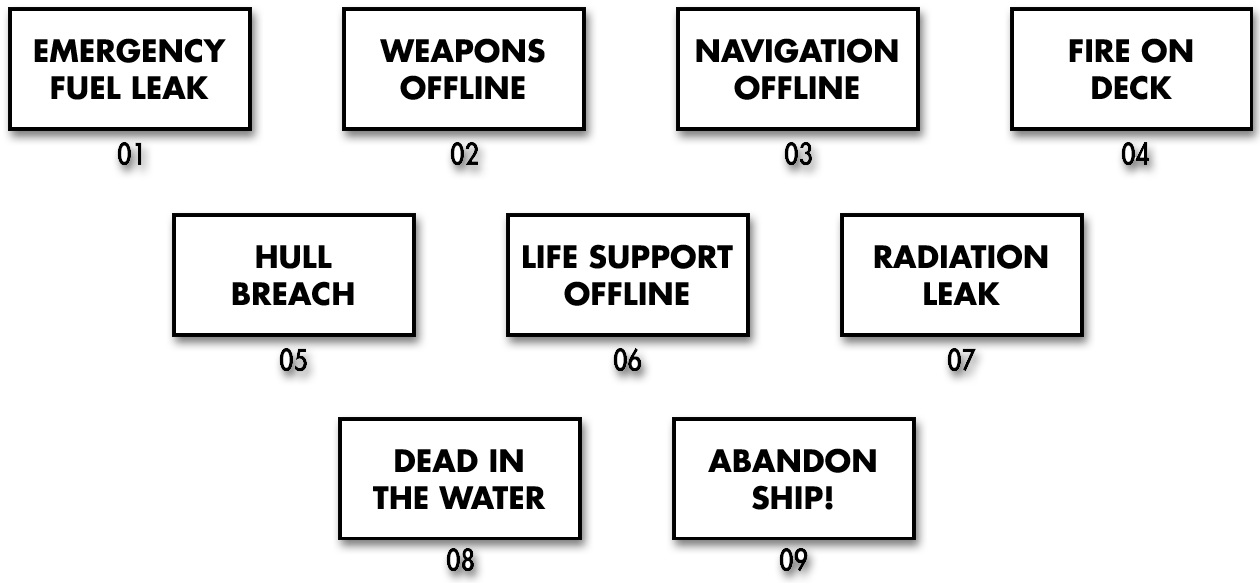

Other Chaotic Effects: At the GM’s discretion, each 1 rolled on the time dilation check instead triggers a different chaotic effect. Examples might include:

- a crew member is replaced by a completely different person

- time dilation is inverted (the trip takes minutes or seconds instead of days) or reversed (they arrive before they left)

- subjective time experienced by the crew is dilated instead

- strange hallucinations or manifestations

- crew is unexpected awoken from cryosleep during the voyage

- the ship arrives in the wrong place

ASTRONAVIGATION

Calculating a jump requires an Intellect (Hyperspace) check. This check is made with [+} if the astronavigator remains awake during the jump, monitoring the astronavigation computers.

Success: You made it!

Critical Success: Roll one fewer d10 when making the time dilation check for the jump. For a Jump-1 trade route, roll 2d10 and only have the ship experience time dilation if both dice roll a 1.

Failure: Something goes wrong! The GM chooses one:

- Double the number of dice rolled for the time dilation check.

- The ship arrives in the wrong place. (1 in 10 chance you arrive back where you started after 4d10 days, having traversed a Calabi-Ricci spacetime loop.)

- The ship is damaged by jump turbulence, roll a Repair (SBT, p. 39).

Critical Failure: You could have killed us all! All three consequences of Failure happen simultaneously.

TRADE ROUTES

According to the Shipbreaker’s Toolkit, “regular Jump-1 trade routes seem to wear down the chaotic effects” of jump travel. Navigational calculations become more precise with each additional jump that’s recorded along a route, and ships traveling through the jump point can effectively wear a “groove” into spacetime.

At the GM’s discretion, ships jumping along a route which has been “worn” by regular travel reduce the number of d10s rolled for the time dilation check by one. For a Jump-1 trade route, roll 2d10 and only have the ship experience time dilation if both dice roll a 1.

UNCHARTED JUMPS

Most interstellar travel happens along charted jump routes: Jump points that have well-plotted navigational solutions (even if they shift slightly due to stellar drift) and are known to be stable.

These are not the only jump points in space, however. Once you’re away from planets, asteroids, and stations, it turns out there are many unstable points in the fabric of space which are constantly being created, destroyed, and shifting according to complex spacetime geometries.

The GM determines the base Jump rating of the uncharted route. (This can usually default to the total value of all Jump-ratings along the known path from the current system to the destination system. For example, if you could normally get to the other system through a known Jump-1 route, the base Jump rating for an uncharted route would also be Jump-1. If you would normally need to make a Jump-1 followed by a Jump-3, then the base Jump rating for the route would be Jump-4.)

Plotting the uncharted jump requires an Intellect (Hyperspace) check. This includes identifying the location of the jump point you need to use, which you will then need to travel to (as shown on the table below). If you’re in the Inner System or in orbit around a planet, increase the time required by one step. (Weeks become months.)

Success: Add 1d2 to the base Jump rating. This is the Jump rating of the uncharted route, which is then resolved normally.

Critical Success: -1 to the base Jump rating (minimum 1). In addition, roll 1d10. On a roll of 1, the jump path you’ve discovered is a new stable route. (Depending on the value of the route, selling the location of this new jump point might be worth thousands or millions of credits.)

Failure: Add 1d5 to the required jump rating. If you roll 5, roll again and add the result to the jump rating. If the result is 10 or higher, you have been unable to find any jump points leading to your desired destination.

Critical Failure: You thought you could get from here to there via a safe jump, but you were very wrong. Your Astronavigation check automatically fails. In addition, determine the jump rating as per a Failure, but you attempted the jump no matter what the result is. If the result was higher than the rating of your Jump drive, your ship suffers 1d2 MDMG and emerges from hyperspace in a completely random and unexpected location. (This is a good way to end up adrift in interstellar space.)