Let’s talk about gods.

The history and treatment of religion in D&D is fascinating, and it’s had an enduring impact on the treatment of religion not only in roleplaying games in general, but in the fantasy genre as a whole.

Religion, of course, has always been a central part of the game. In the original 1974 edition of D&D, clerics were one of just three character classes (the other two being fighting-men and magic-users). But what, exactly, were these clerics and who/what did they worship? Gods are never explicitly mentioned and religion is only barely hinted at. In the rulebooks there are basically only two points of data.

First, the description of the cleric class, which is almost entirely dedicated to building strongholds at higher levels. Relevant quotes (with my comments in brackets):

- ‘When Clerics reach the top level (Patriarch) they may opt to build their own stronghold, and when doing so receive help from “above”. Thus, if they spend 100,000 Gold Pieces in castle construction, they may build a fortress of double that cost.’ [I don’t believe the intention is literally that the “above” will deliver cash money for the endeavor, but it could certainly be interpreted that way.]

- ‘Finally, “faithful” men will come to such a castle, being fanatically loyal, and they will serve at no cost.’ [Specific breakdowns of troop types are then given.]

- ‘Note that Clerics of 7th level and greater are either “Law” or “Chaos”, and there is a sharp distinction between them. If a Patriarch receiving the above benefits changes sides, all the benefits will be immediately removed!’

A quick contextual note here: Arneson’s original Blackmoor campaign featured a Good vs. Evil dynamic in which those were literally teams: There was Team Good and Team Evil, with PCs belonging to one or the other. Gygax, heavily influenced by Michael Moorcock and Poul Anderson, changed that to Law vs. Chaos, but with the same broad idea that these were more or less ideological alliances. (Which is why the early editions of the game had actual alignment languages.)

The interesting implication here is that the cleric’s alliance to a particular god is irrelevant, only their loyalty to the metaphysical alliance is significant. Furthermore, this alliance only becomes significant when a cleric achieves the rank of Patriarch. And even then, it’s not relevant to their supernatural abilities – which they keep even if they “change sides” – only to the loyalty of the men who have flocked to their service.

Which, if you’ve read Moorcock’s Elric stories, probably also makes sense: Elric had a specific patron of Chaos, but in general people served the Chaos Lords or the Lords of Law or were neutral in their strife. (Note that there are no neutral Patriarchs, strongly implying that there are no Neutral gods/lords.)

The only other source of information on religion in the original edition of the game are the level titles for Clerics, which were (in order):

- Acolyte

- Adept

- Village Priest

- Vicar

- Curate

- Bishop

- Lama

- Patriarch

- Patriarch, 9th Level

- Patriarch, 10th Level

You could hypothetically try to intuit some form of religious institution from this, but the reality is that Gygax — as he often did — simply cracked open a thesaurus and wrote down random entries with little care or concern. The list is clearly influenced by a Christian hierarchy, although whether that’s primarily due to the linguistic bias inherent in an English thesaurus’ selection of words or Gygax’s bias as a Jehovah’s Witness is debatable, but it’s probably the former since the list is pure nonsense. (A curate, for example, is subordinate to a vicar. And then, of course, there’s the abrupt shift to Buddhism before jumping to Eastern Orthodoxy for the ultimate rank of Patriarch.)

TANGENT: THAT OLD SCHOOL RELIGION

But, just for fun, let’s do it. Acolytes and adepts are basically apprentices who are dabbling in the arts of Law and Chaos.

Then you have village priests, vicars, and curates. These are clearly the local or lowest level of religious hierarchy. For the sake of argument:

- Priests are recognized with doctrinal and institutional authority. In a village, there may only be one such priest who oversees the local temple or shrine. (Some villages will be dedicated to Chaos; others to Law. Some might have competing shrines with separate priests dedicated to each. But we might also imagine some local priests who are better thought of as the ambassador between the community and both Law and Chaos; it is less that they “serve” the Lords, and instead that they are diplomatically engaged with them.)

- Vicars are still in charge of larger temples, overseeing at least one priest.

- Curates oversee multiple temples. (This might either be in a larger community that can support multiple shrines, or country curates that oversee temples across a small region.)

Now, in Christian churches a Bishop is someone in a position of authority over a large swath of territory. That’s not compatible with the D&D stronghold rules, though, so let’s instead extrapolate from their claim of apostolic succession (a direct lineage to the original Twelve Apostles): A bishop is someone who, like Elric, has a face-to-face relationship with the Lords of Law and/or Chaos.

(This is arguably not consistent with the mechanics: A 6th level Bishop does not yet have access to the commune spell. But I think a distinction can be drawn between someone who has become of sufficient interest that a Chaos Lord might appear to them for a chat and someone who has gained the puissance to contact the Chaos Lord for themselves – i.e., cast a commune spell.)

Here’s the key to understanding our old school religion, though: At the top of our hierarchy is the Patriarch, which literally means the head of the church. (Etymologically, the Patriarch is the one who rules the ‘family’ of the church.) We know mechanically that when someone becomes a Patriarch they “have control of a territory similar to the ‘Barony’ of fighters.” And we know that the Barony of the fighter is a territory containing 2-8 villages of from 100-400 inhabitants each.

What this means is that religion (or, at least, religious organization) is intensely local. There are no huge religious organizations with a central authority overseeing vast swaths of territory. (Or, if there are, they aren’t the religions that the PCs are part of.) Religion is still a patchwork of very small organizations (that almost certainly have some territorial overlap).

This brings us to the curiosity of the Lama, the stage through which a Bishop (who has opened some kind of personal relationship with a Lord or Lords) must pass in order to become a Patriarch. We also know that this is the point at which the cleric MUST choose to become loyal to either Chaos or Law exclusively.

The title of “Lama” comes from Tibetan Buddhism, but its use is thoroughly confused in English by inconsistent translation and mystic Orientalism. Broadly speaking, though, a lama can be thought of us the spiritual leader of a specific school of spiritual thought. We could therefore think of this progression as such:

- The cleric begins making personal contact with Lords of Chaos and/or Law.

- As they gain the ability to directly commune with these entities, they begin formalizing these relationships. This might be a spiritual synthesis of their religious belief or it might be a more realpolitik negotiated alliance with specific Lord(s).

- In this process, they have effectively created their own religious organization, culminating with the foundation of a religious center or stronghold: The appeal of their teaching, the strength of their spiritual power, and/or the support of the Lord itself causes followers to flock to them.

They have, thus, become a Patriarch — of which, as we’ve established, there are many, all struggling with each other.

One would not necessarily expect this state of affairs to persist: Periods of similarly turbulent religious revivalism in our own history have universally collapsed into one or two successful organizations that subsume or overwhelm the rest. So this might just be the short term reality of the world as it currently exists (perhaps because these Lords of Law and Chaos have only recently made contact with this plane of reality? or because the cosmos is in a liminal period of transition between Law and Chaos?) or it might only be true on the outskirts of civilization (where, conveniently, classic D&D-style adventures typically take place).

It might also reflect the internecine and tumultuous conflict of the Lords of Law and Chaos themselves. The ever-unsettled nature of the Lords reflects itself into the ebb and flow of earthly religions.

SO WHAT IS A CLERIC?

But I digress.

As I noted before, these level titles — and anything of interest we might intuit from them — are not really representative of anything meaningful in the actual worldbuilding of Arneson or Gygax.

So what was a cleric? What was religion at the dawn of D&D?

Specifically, Van Helsing from the Hammer Horror Dracula films.

This is pretty well documented: One of the PCs in Dave Arneson’s Blackmoor game was turned into a vampire and became an NPC antagonist. He was so incredibly dangerous that Mike Carr, one of Arneson’s players and later a TSR editor and designer, proposed the idea of creating a vampire hunter.

The primary focus of the OD&D cleric can actually be seen rather clearly in the fact that although they receive no spells at 1st level, they do receive the Turn Undead ability.

So although we may now think of a cleric primarily as worshippers and could scarcely imagine creating a cleric without picking a specific god for them to worship, the reality is that the original clerics were primarily hunters of the undead drenched in Christian imagery (there are no holy symbols in OD&D, only wooden and silver crosses) who didn’t actually need to make a decision about their religious affiliation until 8th level (which was more or less the endgame of D&D at that point).

RELIGION THEREAFTER

Supplement I: Greyhawk is the first time D&D mentions specific gods. Specifically, magic-users get access to the 9th level gate spell: “Employment of this spell opens a cosmic portal and allows an ultra-powerful being (such as Odin, Crom, Set, Cthulhu, the Shining One, a demi-god, or whatever) to come to this plane.”

Note: Although the Shining One here is sometimes identified as Pelor, I’m near certain that

it’s actually Satan/Lucifer. There are some semi-convoluted Biblical debates about this, but the key thing is that this title is endorsed in a number of Jehovah’s Witness commentaries on the Bible… and Gygax was a Jehovah’s Witness who led Bible study classes.By contrast, I’m not 100% sure when Pelor gained “the Shining One” as one of his apellatives, but I don’t think it’s until the ‘90s.Edit: Geoffrey McKinney, in the comments below, identifies the source of the Shining One as A. Meritt’s The Moon Pool. That is almost certainly correct. Note that The Moon Pool appears in AD&D’s Appendix N.

The other thing that happens in Supplement I: Greyhawk is the arrival of paladins as a sub-class of fighting-men. This further strengthens the Christian basis of religious character classes in D&D, because paladins are just straight-up Charlemagnic holy knights.

Supplement II: Blackmoor briefly discusses a “great struggle of the gods to control the planet,” including the fact that “mermen were created by the Great Gods of Neutrality and Law while the Gods of Chaos bent their will to create the Sahuagin.” (This material would have likely been written by Steve Marsh, or possibly by Tim Kask based on material from Steve Marsh.)

Note: Marsh has cited the inspiration of the sahuagin as being “an old Justice League of America animated show.” I’ve seen people point to “The Invasion of the Hydronoids,” a season two episode of The All-New Super Friends as Marsh’s inspiration, but the date is wrong. (The episode premiered in 1977, after Supplement II was published.) I’m guessing it was actually “The Watermen,” a season 1 episode from the original Superfriends series that would have aired in 1973.

Supplement III: Eldritch Wizardry introduces the Orcus, the Demon Prince. Also notable for our discussion because his rod “causes death (or annihilation) to any creature, save those of like  status (other Princes, High Devils, Saints, Godlings, etc.).” There is also the Throne of the Gods, “crafted by an ancient race in honor of their gods.”

status (other Princes, High Devils, Saints, Godlings, etc.).” There is also the Throne of the Gods, “crafted by an ancient race in honor of their gods.”

In these references we can begin seeing more influence seeping into the game from sword-and-sorcery authors like Robert E. Howard and Fritz Leiber, where a patchwork panoply of mythological and fictional deities are sort of bouncing around.

What’s interesting to me is how the overwhelming Christian influence of both the player-facing character classes and, of course, the players themselves collide with this vaguely invoked pagan pantheism. You can see a rather clear example of the weird gestalt that results a couple years later in T1 The Village of Hommlet. The village church — the Church of St. Cuthbert — is straight-up Christian in its conception and organization: It’s shaped like a cross and named after an actual Christian saint (or possibly a lesser god who is named after a Christian saint).

This is basically not atypical of how D&D religions tend to work by default down unto today: Churches and religions following Christian models (cross-shaped cathedrals filled with priests and bishops), but with a non-Christian god slotted in for Jesus.

SUPPLEMENT IV

Obviously our discussion of religion in OD&D cannot be complete without talking about the elephant in the room — Supplement IV: Gods, Demi-Gods & Heroes by Robert Kuntz & James Ward.

This is a really odd book. It consists almost entirely of stat blocks and short descriptions for a panoply of real and fictional pantheons, fleshed out with a few mythological artifacts and a handful of mortal heroes. There’s no real explanation of what you’re supposed to actually do with any of this stuff. It just kind of… exists.

In the foreword to the book, there are three things that Tim Kask, TSR’s Publications Editor, want you to know:

- He loathed working on Supplement II: Blackmoor. (I cannot express how bizarre it is that the first paragraph of this book is literally dedicated to trashing another book that the company had published the year before.)

- This is the last D&D supplement that will ever be published. “Well, here it is: the last D&D supplement. (…) We’ve told you just about everything we can. From now on, when circumstances aren’t covered somewhere in the books, wing it as best you can.” He later returns to this theme at the end of the foreword to say that everyone should buy TSR’s magazines. “Just don’t wait with baited breath for another supplement after this one. May you always make your saving throw.”

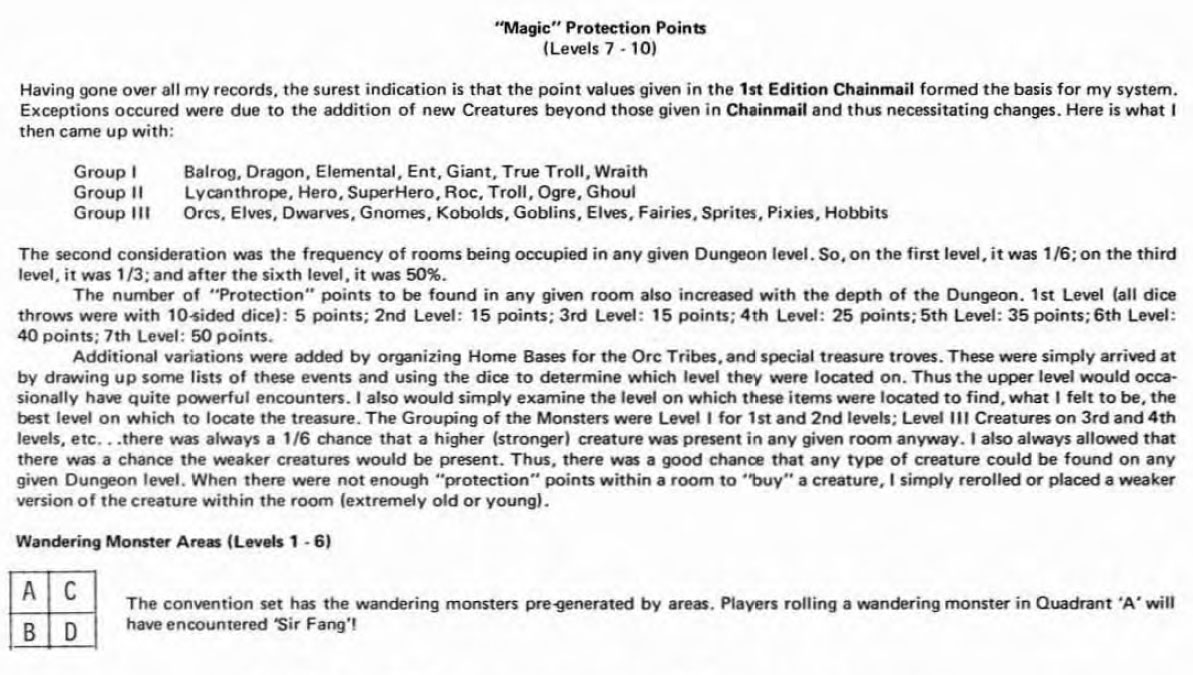

- “This volume is something else, also: our last attempt to reach the ‘Monty Hall’ DM’s. Perhaps now some of the ‘giveaway’ campaigns will look as foolish as they truly are. This is our last attempt to delineate the absurdity of 40+ level characters. When Odin, the All-Father has only(?) 300 hit points, who can take a 44th level Lord seriously?”

Of course, after reading this imprecation against overpowered characters, you will immediately turn the page to a book dedicated almost entirely to giving you combat stats for gods so that you can kill them.

Four years later when this concept was revisited for the hardcover Deities & Demigods supplement, editor Lawrence Schick was quick to say that the obvious purpose of these stat blocks was NOT in fact the purpose of these stat blocks:

But what exactly is it? Let’s see, it has a nice cover — open it up, inside there are lots of pictures next to sets of stacked statistics… it must be just like the MONSTER MANUAL! There, that was easy. Now that we know what it is, we know what to do with it, right?

Wrong.

DDG (for short) may resemble MONSTER MANUAL, and in fact does include some monsters. However, the purpose of this book is not to provide adversaries for players’ characters. The information listed herein is primarily for the Dungeon Master’s use in creating, intensifying or expanding his or her campaign.

Of course, the “Explanatory Notes” on the exact same page tell you that the gods’ Armor Classes are “a measure of how difficult it is to hit” them and their Hit Points “indicate the amount of damage a creature can withstand before being killed.” So… take it with a grain of salt.

Gary Gygax, in his foreword to the book, is more explicit about what the book is for:

In general, deities are presented in pantheons. You can select which ones, combinations, or parts of pantheons best suit your campaign. Players knowing which gods are “real” in the campaign world are able to intelligently choose to serve one (or more) suitable to the character’s alignment, profession, and even goals.

In this, Gygax makes explicit something that was only implicit in the organization of Supplement IV: That gods organize themselves into pantheons. This might initially seem like a, “No kidding,” statement, but it’s rather likely you’re only thinking that because D&D so heavily popularized this concept.

In sword & sorcery fiction like Howard and Leiber, various cultures — just like in our own world’s history — had collections of gods that they worshipped. But these associations were usually implied to be the result of the people worshipping them rather than because the gods themselves had stratified social circles. And, as a result, gods might be found in several different “pantheons” (i.e., worshipped in various locations that had overlapping sets of gods that they worshipped).

There were certainly exceptions to this: The handling of the Asgardian gods in Kirby’s Thor comics, for example. Or the divisive war between Moorcock’s Chaos Lords and Lords of Law. It just wasn’t the presumed default.

This de facto introduction of the pantheon more or less completes the weirdly incoherent metaphysics of D&D religion, in which:

- Gods are arranged into pantheons, a word literally derived from the Greek word for a temple which worshipped all gods, and yet…

- People (including the clergy) almost universally choose just ONE god to worship because…

- Every civilized god gets slotted into a church based on monotheistic Christian rites, architecture, and organization. (“Evil” gods are slightly more likely to get primitive fanes and the like.)