I have previously read (and reviewed) two other products from Guardians of Order: Big Eyes, Small Mouth (the first generic anime RPG) and Big Robots, Cool Starships (a vehicle construction system for BESM). I approached each of these books with a certain degree of doubt: Anime is capable of anything, so isn’t a generic anime game just another anime game? A simple vehicle construction system? Isn’t that an oxymoron? In each case, not only did the doubts vanish, but the books proved themselves worthy of lavish praise.

I have previously read (and reviewed) two other products from Guardians of Order: Big Eyes, Small Mouth (the first generic anime RPG) and Big Robots, Cool Starships (a vehicle construction system for BESM). I approached each of these books with a certain degree of doubt: Anime is capable of anything, so isn’t a generic anime game just another anime game? A simple vehicle construction system? Isn’t that an oxymoron? In each case, not only did the doubts vanish, but the books proved themselves worthy of lavish praise.

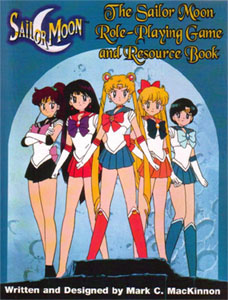

The Sailor Moon Role-Playing Game and Resource Book (henceforth the Sailor Moon RPG) was no exception when it came to doubts. I had no worries about the game itself (which uses a specially modified version of the TriStat engine used in Big Eyes, Small Mouth), but with the source material: Even if I was impressed with how well Guardians of Order had translated the Sailor Moon television series into game terms (and that was no sure thing, licensed products are devilishly hard to do properly), quite frankly, I didn’t really think the material itself was going to do anything for me. I’m not a rabid Sailor Moon hater – quite the opposite, I mildly enjoyed the handful of syndicated episodes I saw (although, per usual, I have issues with the American translation, dubbing, and censorship), but it simply didn’t seem the type of thing which was going to send me dancing through the streets singing its praise.

Well, I’m not dancing, but I’ll tell you right up front that Guardians of Order has successfully pulled the rug out from under my expectations once again.

THE RULES

The Sailor Moon RPG uses a customized version of the TriStat System, Guardians of Order’s house system originally used in its generic form in Big Eyes, Small Mouth. In my review of BESM (found elsewhere on RPGNet), I have given a comprehensive overview of the basic TriStat mechanics. Therefore, for the Sailor Moon RPG I am just going to briefly go over how those rules have been customized. Anyone curious in any specifics which I don’t mention here can, of course, take a look at my review of BESM.

Starting at the top of character creation: One of my minor problems (and they were all minor) with BESM was that stat generation defaulted to a random state (2d6+10 points which are distributed among the three stats), with the non-random options isolated at the back of the book. The Sailor Moon RPG not only corrects this problem, but goes one step better. Two methods are presented by which the GM can determine stat points: In Method A the GM gives everyone the exact same number of stat points. In Method B every character is given a static number of stat points, which is then modified by a random roll.

What seems to be missing are the options for unbalanced character creation – so that some characters will have more stat points than others. This option is given for the generation of attributes, so its oversight in stat assignation is odd. On the other hand, since there are attributes which modify the basic stats, you can get the same result through indirect means.

The character attribute system itself is a proto sub-attribute system. I describe it that way, because by the time I read the Sailor Moon RPG I had already read Big Robots, Cool Starships which develops and refines the mechanic in order to create a phenomenal vehicle construction system (reviewed elsewhere on RPGNet).

In the Sailor Moon RPG the sub-attribute system is used to specifically model the special powers of the Sailor Scouts (known as Sailor “Senshi” or “Knights” in the original Japanese) as well as the special powers of their Negaverse (or “Dark”) foes. Specifically you spend some of your Character Points to purchase either the Senshi/Knight Powers attribute or the Negaverse/Dark Powers attribute. For each level of these attributes you purchase, you get 10 Power Points in order to buy the sub-attributes which you are given access to (such as “Item of Power” or “Mind Control”).

And that about does it as far as customization goes.

This customization process works quite well with the TriStat system – which, due to its simplicity, take no more than half a dozen pages or so to explain (plus the particular attributes, many of which are specialized to the Sailor Moon universe). As a result you end up with a complete, stand-alone game which is also 100% compatible with other TriStat products. If you bought the Sailor Moon RPG first, for example, you could go out and buy Big Eyes, Small Mouth and use the attributes there to expand the scope and depth of your game. When GOF releases their licensed Dominion Tank Police game, you’ll be able to do crossovers easily. And so on. Nothing extra is required to play, but everything becomes an addition to your game.

THE RESOURCE BOOK

The other interesting thing about this book is that it is presented as the Sailor Moon Role-Playing Game and Resource Book. What’s this “Resource Book” stuff?

Well, this is not just a game – a large portion of the book is dedicated to being a general resource guide for fans of the Sailor Moon television show. So you get some general background on Japan (including the particulars of how their school system functions); a guide to the places seen in the Sailor Moon TV show; a Sailor Moon timeline; a “travel guide” to the Negaverse, the Moon Kingdom, the Planet of Makaiju, Crystal Tokyo, and Nemesis the Dark Moon; a character guide to all the major and minor characters; an overview to the mythological references made in the series; an episode guide complete with summaries; a bibliography of Sailor Moon’s creator (Naoko Takeuchi); a guide to Japanese pronunciation (and a minor glossary of some major terms relating to Sailor Moon); a guide to the meaning of the character’s names; a reference to the Sailor Senshi attacks (and translations of them); a yoma/cardian/droid list; a guide to on-line Sailor Moon resources; translations of the opening songs; and a credit list for the creative personalities behind the show.

As you’ve probably already noticed, a large amount of that stuff is fairly typical of what you’d see in any RPG – setting information. So why call it a “Resource Book”? Because by calling it a resource book, Mark MacKinnon is able to get the book into places where an RPG could never go. People who would never see (and would never consider buying) such a roleplaying game, will see (and perhaps even buy) this book. Recent reports seem to be bearing the theory out.

And that’s great. The young females who are the primary (but not only) audience for Sailor Moon are precisely the demographic to which RPG’s have never appealed. Indeed, I can’t think of any better property which could be developed than Sailor Moon which would both appeal to these new fans, and also have some potential of attracting established roleplayers. Nor is there any system better built than the TriStat System to function as an introduction to roleplaying. Anyone with young daughters or nieces who they would like to get interested in roleplaying could probably do no wrong in giving them a copy of this book as a birthday or Christmas present.

THE SETTING

If you’re anything like me, you’ve probably been reading this review with a bit of a jaundiced eye. Sure, the system is nice. Sure, the presentation is superb. Sure, the game functions great as an introduction for new players. But play a bunch of pubescent girls who run around in skimpy outfits?

A digression is called for.

One of my favorite RPGs is Amber, a game based on the series of popular fantasy novels by Roger Zelazny. Although I find its system to be tremendously innovative, what draws me back to the game time and time again is the setting. For whatever reason the basic Amber canon, as described by Zelazny, functions only as a starting point for a host of variation. I, for example, have played in a variation where Amber was completely destroyed, and another where the entire Court was replaced with alternates (King Oberon became Queen Titania, Dworkin the ancient man became Rozel the young female, the players assumed the roles of a brand new set of children, and so on). Some have theorized that this was brought about because of the unreliability of the narrator in the original Amber books (was he really telling the truth? or was his version merely a plot to accomplish something else?); others point to the basic necessity of any licensed property to modify the canon in order to leave a place for the PCs to participate; and some have pointed to Wujcik’s decision to model multiple interpretations of the major characters in the main rulebook. In my opinion all of that had something to do with it, but when you boil it all away, Zelazny based his world on strong mythological archetypes. Those archetypes are extremely resiliant to massive amounts of change, and indeed, have been subject to thousands of alterations over the course of human history. It is little surprise, therefore, that Amber not only stands up under such change, but thrives under it.

In any case, the world of Amber has been twisted and distorted in any number of interesting and original ways. It’s fan community is a vibrant thing in which ideas are swapped and every conceivable alteration and possibility is considered, adapted, and used in various combinations.

I bring all of this up because I see the same potential in the Sailor Moon RPG, with the same type of groundwork being laid (almost certainly unintentionally) by Mark MacKinnon as was laid by Eric Wujcik. The basic mythological themes of Naoko Takeuchi’s characters and plots, combined with the need to modify the canon for a roleplaying game, leads inexorably to the great potential found in variating the Sailor Moon Universe. I have already considered several interesting possibilities (including one in which the Sailor Moon manga and anime series are a set of propaganda films distributed by the evil Sailor Senshi, while the truth is that the Negaverse is fighting to protect our world from their machinations and eventual domination).

As for “playing young girls in skimpy outfits” being a problem for you, the method of your salvation is built right into the game. Rules for creating Knight characters (such as the Tuxedo Mask from the series) are built right into the system. I immediately began pondering the possibility of a campaign where all the PCs are Knights, while the Sailor Senshi were relegated to fulfilling roles similar to that of Tuxedo Mask.

A COUPLE OF BAD THINGS

I came across two things in the Sailor Moon RPG which are regrettable:

First, many of the attributes discuss and use Energy Points to one degree or another. The only problem here is that you don’t find out what “Energy Points” are until Step Six of Character Creation (because its a Derived Stat), while the Attributes are discussed in Step Four of Character Creation.

Second, the Sailor Moon RPG suffers from what I’ve begun to call the “Guardians of Order Index Problem” – in which every entry in the index has exactly one reference. For example, according to the index, Sailor Moon is only mentioned once in the entire book (the reference is to her character sheet write-up). There is actually one exception to this: Each episode of the Sailor Moon TV show ends with a segment called “Sailor Moon Says” in which a little moral is provided for the day’s story. MacKinnnon used these to great effect throughout the book as boxed text, often finding very appropriate ones which complemented what the main text was discussing. In the index all four of these are mentioned.

CONCLUSION

I highly recommend the Sailor Moon RPG for five reasons:

First, the “Resource Book” portion of the title should be considered anything but tacked on. It is the first such resource book published for Sailor Moon in the States, and it is a wonderful resource. Any fan of the Sailor Moon TV show would definitely enjoy the book just for its reference purposes.

Second, it acts as a wonderful (if previously unmentioned) showcase for Sailor Moon art. The text is liberally sprinkled with highly appropriate selections from the manga and anime, including a full color section of pin-ups.

Third, the Sailor Moon RPG acts as a showcase for the enduring strength of the TriStat system. It’s sub-attribute system, as well as the host of new attributes introduced for the Scouts and Negaverse powers, would be useful in quite a few BESM games.

Fourth, I think that the Sailor Moon universe has tremendous flexibility and potential. The Japanese have far more respect for their children’s media tastes than American cartoon makers typically do, and as a result Sailor Moon benefits greatly from an unexpected depth of character and unique mythology. As a result, campaigns set both within and without the “canon” the series have a surprisingly huge amount of rich source material to draw from.

Fifth, and finally, the Sailor Moon RPG acts as an excellent introductory volume for roleplaying – particularly for young girls and fans of the Sailor Moon anime and manga. I have a cousin who, when she gets a couple of years older, will probably be getting a set of Sailor Moon tapes, some Sailor Moon manga, and a copy of this book. I’ll corrupt her yet.

For some this book will just be silly; but for many it will hit the nail right on the head. In short, I can’t say “every roleplayer will enjoy this book”. However, I think every roleplayer who has a broad palate should at least give the book a try… particularly if anything in this review has caught your interest.

Style: 5

Substance: 4

Author: Mark C. MacKinnon

Company/Publisher: Guardians of Order

Cost: $25.00

Page Count: 209

ISBN: 0-9682431-1-8

Originally Posted: 1999/08/16

This really was a groundbreaking RPG and the “Resource Book” approach was, according to all reports and evidence, highly effective at reaching out to new players. It was one of the few instances where I feel a small RPG company was actually really, really successful at reaching outside of the existing hobby.

Unfortunately, within a few short years the internet had grown to a point where “Resource Books” were irrelevant: Online resources and wikis wholly replaced them. It’s probably not wholly coincidental that Guardians of Order didn’t last very long after that. As I said in my review for BESM, I miss ’em. They came close to nailing something really special, but in the end they missed it.

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.

The Complete Book of Yoma: Volume 1 is the seventh Guardians of Order book I’ve reviewed for RPGNet (Big Eyes, Small Mouth; Big Robots, Cool Starships; The Sailor Moon Roleplaying Game and Resource Book; and the three Sailor Moon Character Diaries being the others). I continue to be impressed with their efforts, as the company steadily makes it way closer and closer to a hallowed inclusion on my “buy everything these guys do” list. The Complete Book of Yoma is a resource almost any GM of the Sailor Moon roleplaying game should make an effort to get their hands on.

The Complete Book of Yoma: Volume 1 is the seventh Guardians of Order book I’ve reviewed for RPGNet (Big Eyes, Small Mouth; Big Robots, Cool Starships; The Sailor Moon Roleplaying Game and Resource Book; and the three Sailor Moon Character Diaries being the others). I continue to be impressed with their efforts, as the company steadily makes it way closer and closer to a hallowed inclusion on my “buy everything these guys do” list. The Complete Book of Yoma is a resource almost any GM of the Sailor Moon roleplaying game should make an effort to get their hands on.