Location-based adventures are a staple of the GM’s art and form a kind of bedrock for scenario design. Even if a scenario isn’t primarily about ‘crawling a specific location, you’ll still find yourself frequently keying a map to describe wherever the action is taking place.

Which is why I find it fairly surprising that the location keys in published adventures are almost universally terrible.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE KEY

In 1974, the original edition of D&D included a “Sample Map” keyed with both numbers and letters. The description of the key, however, was instructional rather than practical. For example:

5. The combinations here are really vicious, and unless you’re out to get your players it is not suggested for actual use. Passage south “D” is a slanting corridor which will take them at least one level deeper, and if the slope is gentle even dwarves won’t recognize it. Room “E” is a transporter, two ways, to just about anywhere the referee likes, including the center of the earth or the moon. The passage south containing “F” is a one-way teleporter, and the poor dupes will never realize it unless a very large party (over 50’ in length) is entering it. (This is sure-fire fits for map makers among participants.)

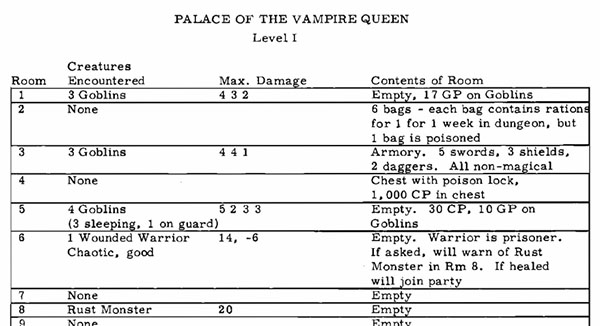

Skip ahead a couple of years to 1976, though, and we’ve reached Year One for published adventures: Arneson’s “Temple of the Frog” appeared in Supplement II: Blackmoor; Wee Warriors released Palace of the Vampire Queen; Metro Detroit Gamers released the original Lost Caverns of Tsojconth; and Judges Guild released Gen Con IX Dungeons and City-State of the Invinicible Overlord.

Palace of the Vampire Queen featured a completely tabular key that looked like this:

The Lost Caverns of Tsojconth, on the other hand, featured the Gygax “wall of text” key which would become a staple at TSR for the better part of a decade:

K. COPPER DRAGON: HP: 72. Neutral, intelligent, talking, has spells: DETECT MAGIC, READ MAGIC, CHARM PERSON, LOCATE OBJECT, INVISIBILITY, ESP, DISPEL MAGIC, HASTE, and WATER BREATHING. It is asleep but will waken in 3 melee rounds or if spoken to or attacked. It will bargain to allow the party to pass on to the east if given at least 5,000 GP in metal and/or gems/jewelry – deduct 1,000 GP for each magic item offered instead. It will tell the party nothing, but it will ask about the fire lizards. If the party has slain these creatures, the dragon will attack them. 30,000 CP, 1,000 GP, 36 100-GP gems, 42 500GP gems, 13 1,000-GP gems, 9 pieces of jewelry (9,7,7,6,5,4,,4,3,3 in 1,000’s each). A jeweled sword (quartz), non-magical, will be hated by party’s swords at first, value is 783 GP. An ivory tube with contact poison contains a scroll of 3 spells (MONSTER SUMMONING III, LIMITED WISH, SYMBOL). Several pieces of jewelry radiate magic (they have a magic mouth spell on them with a nearly impossible speak command) for a 10th piece of jewelry is a necklace of missiles (5), with each missile globe encased in an ivory block (which can be pried open along a hairline seam to reveal the missile).

In Gen Con IX Dungeons, meanwhile, Judges Guild was way ahead of the curve (as was so often the case). Bob Blake had recognized that a key with better organization would make it easier for DMs to run the adventure, and he introduced that organization by including a “DM Only” section in each key entry:

13. 30’ N-S, 30’ E-W. Enter by secret door in center of W Wall. There is a blackened firepit in the center of the room, and a barred opening into 10’x10’ opening in the center of the E Wall.

DM Only: The firepit contains nothing of value. The portcullis may be easily raised by pulling on a chain hanging from a small hole in the wall next to the portcullis. There is a secret door in the E Wall of the alcove.

Although not technically boxed text, this format was effectively accomplishing the same thing on a structural level. (Particularly interesting are the keys which feature two separate “DM Only” sections – one before the player section and detailing information necessary when entering the room and one after the player section detailing information on what investigating the room will reveal.)

Unfortunately, although Blake used this format through 1977, Judges Guild eventually abandoned it and also moved to “wall of text” keys.

In 1978, B1 In Search of the Unknown effectively created the idea of separating the key into distinct sections:

30. ACCESS ROOM. This room is devoid of detail or contents, giving access to the lower level of the stronghold by a descending stairway. This stairway leads down and directly into room 38 on the lower level.

Monster:

Treasure & Location:

Although this division superficially resembles later “adventure formatting guides” (which we’ll get to momentarily), it was actually an accidental by-product of In Search of the Unknown being designed as a training tool for beginning DMs: The adventure included prepared lists of monsters and treasures which the neophyte DM was supposed to assign to various rooms throughout the dungeon. (Which is why those sections are blank in the example above.)

THE ERA OF BOXED TEXT

In either 1979 or 1980, depending on how persnickety you want to get with definitions, boxed text — prewritten text designed to be read aloud by the GM — arrived for the first time in Lost Tamoachan: The Hidden Shrine of Lubaatum, a tournament module by Harold Johnson & Jeff R. Leason that was originally printed for the Origins game convention.

In the original version of the module, the text was not yet boxed, instead appearing between quotation marks:

But in 1980, TSR reissued the module as C1 The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan, placing the prewritten descriptions in a box for the first time:

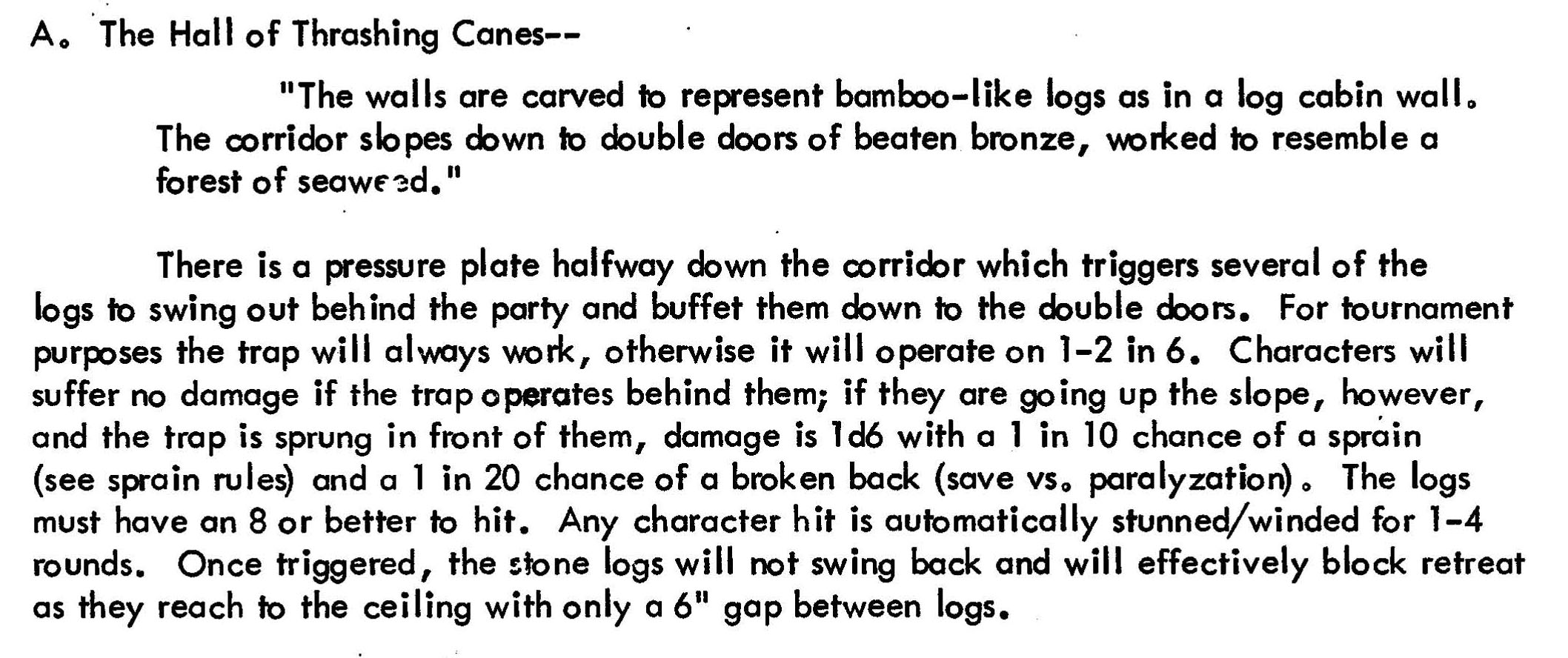

![2. The Hall of Thrashing Canes:

[BOXED TEXT] The sides of this corridor are carved to resemble walls of bamboo-like logs. The passage slopes down from a single door on its western leg, the lintel of which has been crafted to represent a stylized cavern entrance, to double doors of beaten bronze, worked to resemble a forest of seaweed. [END BOXED TEXT]

There is a pressure plate halfway down the hallway which triggers a trap. Several of the logs will swing out from either wall and buffet the party towards the double doors. For tournament play, the trap will always work. For campaign adventure, the trap will be triggered on a 1 or 2 in 6.](https://thealexandrian.net/images/20140519f.jpg)

Like Blake’s “DM Only” section from earlier in the decade, the boxed text clearly delineated the elements of a given area that should be immediately shared with any PC entering the area.

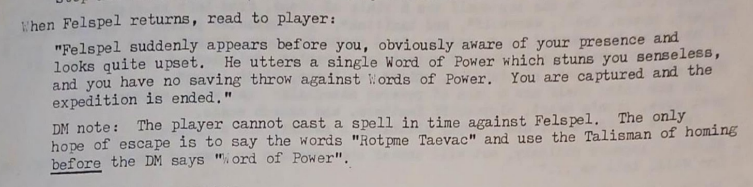

Later, of course, the role of boxed text would be expanded to include any sort of “read-aloud” text intended for the players, but its function as a narrative device is beyond the scope of location keying. In this context, however, an honorable mention should perhaps be given to Quest of the Fazzlewood, a 1978 “head-to-head” tournament module designed to be played with just one DM and one player. In addition to a lengthy introduction designed for the player to read, the finale of the adventure is presented with read-aloud text:

(photo from Explore: Beneath & Beyond)

The formatting is quite similar to the later Lost Tamoachan, and one could argue that this is, in fact, the first example of “boxed text” (albeit of the not-yet-boxed variety).

In any case, at this point, things basically settle down: When Dungeon #1 appeared in 1986, it still featured the familiar boxed text paired with a “wall of text” key for the DM. In 1988, monsters and NPCs in the magazine received a standardized stat block that gets clearly delineated from the text. But that basic format can still be seen in The Apocalypse Stone in 1999 (the very last adventure produced for 2nd Edition).

ADVENTURE FORMATTING GUIDES

When 3rd Edition arrived, however, an effort was made to introduce a new “standard format” for published adventure modules. First appearing in The Sunless Citadel, this format had the familiar boxed text and wall of text, but supplemented this with a specific set of bold-faced sections:

- Traps

- Creatures

- Tactics

- Development

- Treasure

Not all of these appeared in every location, but if they did appear then they appeared in that order and no other.

As noted above, this format recalls B1 In Search of the Unknown. There were also a handful of other examples between 1978 and 2000, most notably 1982’s I3 Pharaoh which featured headings for:

- Play

- Lore

- Monster

- Character

- Trap/Trick

- Treasure

Tracy and Laura Hickman, the authors of Pharaoh, also dedicated a full page to explaining what each section of their key was designed to accomplish. For example:

Play: This outlines the general sequence of events that may take place in the room. For example: “Players entering the room from the door must first encounter the Trap, which releases the Monster. Only by defeating the Monster can the Treasure be found.” Play explains the general order that the sections should be used. Additional size and dimension information about the area is also included here.

And that largely explains what the intended purpose of the standardized adventure format is: To break up the wall of text and clearly communicate to the DM where they should look for a given piece of information.

It’s a noble intention, but the problem with this specific approach to adventure writing is that it tends to encourage writers to “fill the format”. You probably don’t really need to tell a DM that the orcs attack people using their swords (since that’s the only weapon they have)… but the format says you should have a “Tactics” section, so you might as well write two or three paragraphs about it.

An even bigger problem, in my experience, is that of sequencing information: A room with an ogre standing in the middle of it should talk about the ogre first; a room with a goblin hiding behind a tapestry, on the other hand, shouldn’t lead off with the goblin.

This sort of one-size-fits-all formatting becomes both a straitjacket and an excess. And the culmination of this approach is the infamous “delve” format, which I’ve talked about extensively elsewhere.

The fundamental problem (which the delve format simply metastasizes) is that the rigid adventure format forces information to be presented out-of-sequence or breaks that information up in a way that doesn’t make sense during actual play. Instead of making the information easy to parse and reference, a rigid format ends up having the opposite effect.

THE ART OF THE KEY

Part 2: The Essential Key

Part 3: Hierarchy of Reference

Part 4: Adversary Rosters

The link to part 2 seems to be a trap, but I cannot find the boxed text to explain it.

Map Key writing is a form of writing. Stuff that became staples of D&D adventure writing has existed previously in experimental literature of the 1960’s. Among the famous forms was the choose your own adventure story, and random story – rolling a die or flipping a coin to see which page to read next, something akin to randomly stocking a dungeon. Of the literary experiments that did not survive, was the “novel in a box” – a box with 100 pages of text. You were supposed to toss it about randomly on your bed, put the pages together again, and read the story.

Of the greater concern is that adventure key writing works best with tactical, site based adventure – the map of the dungeon is the flowchart, along which the adventure story takes place; this model has been adopted with decreasing success, as a wilderness hex crawl, and it did not progress beyond that.

There are several reasons, why adventure writing did not evolve. First was that the actual game process that inspired D&D was a lot more involved and complex, and the white box rules were only a barest approximation. Essentially people played a table top miniature war game. Players felt affinity for the miniature figures that represented them. They started projecting personalities on them and engaging in the improvisational role-play, that was facilitated and adjudicated on the spot.

When the D&D rules were published, the product was a totally different game, that did not make a lot of sense unless you learned informally how to play. To make the matters worse, when AD&D came out, an example of the D&D game was written to illustrate the rules and the game play. That example was recycled in the WOTC edition. The problem with that was that the example did not come out of the real gaming experience, but was purpose written for the DMG, so the map, or the example was not real play. Same thing happened in the Moldway red box set, with a dramatic example of play and of the dungeon adventure design. Keep in mind, that I think that the two-page how to design a dungeon adventure section in that boxed set is the best piece of writing on the adventure design that I have to date! The problem is that these examples were not taken from real life games, but were written as fiction of how the game is supposed to be played, if you will. The real problem was that there were staff writers creating dungeon modules, and there were game mechanics for creating random dungeons up until the AD&D 1st edition. Subsequent editions of D&D relieved the DM of the burden of writing his or her own dungeon or other adventures. What remains is an illusion that a good adventure can be randomly generated. The truth is, when a commercial dungeon is written, it is carefully designed, written and play-tested by paid staff writers promoting the game; there is nothing random in these products. Naïve DM’s think that they can accomplish the same by following the random story generators in the rule books. James Maliszewski, did just that, and even though he had both imagination and an original vision, the random generated nature of his mega dungeon was what tuned off people the most.

I have banged my head against he wall trying to come up with ways to write adventures that would go beyond map keys and hex crawls, that would convey the right amount of detail and convey the full richness of true exploration, and I am still working on it. I have made some head way, it is extremely challenging, and I love rolling up random treasure and randomly stocking excess rooms with traps, monsters, and treasures, but it is a guilty pleasure.

@ Brooser Bear,

Some interesting insights and comments you have there.

*”The problem with that was that the example did not come out of the real gaming experience, but was purpose written for the DMG, so the map, or the example was not real play. Same thing happened in the Moldway red box set, with a dramatic example of play and of the dungeon adventure design.”

I bought and read through the Moldvay Basic a few months ago, and agree that it has a lot of good things to recommend it as a clear guide to learning to play and run adventures in D&D. It also addresses issues you need to deal with as a guide to making up your own simple gaming system.

Rereading the DMG pages 97-100, which lay out the sample “First Dungeon Adventure,” besides Gygax’s atrocious poseur-writing style, and his presentation of the players’ diction being unrealistic, what are your issues with it as being meaningfully divergent from an actual guide to play at the table? How would it have been improved? Sure, Gygax has the players tending to elaborate their logic for an offstage 3rd party reader, which they pretty much wouldn’t do in real life, but that doesn’t strike me as being a problem as a guide to play. I think that’s a stilted convention, but an acceptable way for the author to clue the reader in to the logic behind party marching order, etc. Actually, I think he created a pretty interesting introductory example of an adventure, here. And for all the hero-worship that guy gets, I’m not a fan of most of that man’s work, so that’s saying something.

*”Naïve DM’s think that they can accomplish the same by following the random story generators in the rule books. James Maliszewski, did just that…”

I remember back in the day trying to randomly generate maps and stock dungeons from the DMG, and being pretty disappointed. The maps were hopeless. Some blogs have mentioned that you can stock dungeons with the random tables, and it’s a challenge to figure out reasons for why the creatures you randomly rolled, are in the locations they are in. That might be true, I guess. I still think you’d have to ignore some of the rolls, to make it a non-funhouse experience, that has some kind of rational ecology to it. Even at 13 years old, I remember asking myself “Why aren’t all these monsters killing each other off, long before the PCs get into this dungeon? Why don’t the dragons come up from the 10th level and eat the nearest available easiest large source of meat, namely, all the goblins on 1st level?” A blast of fire, and it’s chicken mcnuggets, and an empty level of hallways and scorch marks.

No realism in that kind of set-up. To my mind, if you don’t have that realism, the experience diverges from day to day considerations too much, and you can’t draw on experience to make predictions leading to rational, meaningful decisions. Everything is just there because the dice randomly say they are, and nothing makes a bit of sense, or has any reasonable history.

There’s also the advice that you should only stock every 3rd room with some kind of encounter. That strikes me as being pretty high. If nothing else, that many living entities or traps would make lots of noise from fights, and alert each other, continuously. What were the rules on noise and closed doors, or distances combat was heard down a hallway? In real life, you can hear your neighbors fighting down a hallway, so I wonder how that translates into a stone-faced dungeon/castle environment.

Neal,

Random dungeon generation can make a lot of sense and work like a charm, if the DM understands the game and takes an additional step to write the tables, from which the dungeon is randomly generated. Any role playing game adventure is a story, like any other piece of prose. It needs players participation to complete it and it also needs to be narrated, that’s self obvious nonsense, but the next step is where a lot of confusion occurs: The Dungeon is several things all at once: It is the PLACE or a SITE, where adventure takes place; it is the SETTING, where the story takes place, it is the STORY, and it is the SCHEMATIC that makes the story accessible to play.

As a schematic, the dungeon is a flowchart for the adventure – Rooms contain Encounters which players must overcome, connected by corridors. And most people leave it at that. But consider representation of a village – each hut is a room, some ay have more than one, and there are no corridors. You get into wilderness exploration, representation to make for a realistic exploration and narrative becomes more complex yet. Now, let us say we have a troop of goblins. You can locate them in a bunch of rooms in a dungeon, but just the same, you can also locate them in a bunch of houses in a village they have overrun, coexisting with terrified peasants who wait on them hand and foot, the reluctant peasants hanging from trees in a nearby orchard, or maybe this is a goblin village with the indigent and the young running around, or maybe this is a goblin encampment, where each room is a tent or a dugout centered around a farmhouse. See, the schematic is the same, but the place is different in each one. In addition, as a setting, the dungeon must reveal itself to the players and in turn, the dungeon and the players must be a part of the same story. The Story part of the adventure design is addressed pretty well in Moldway red set, the Setting part is glanced over in the “Decide on the Special Monsters to be used”. In literature, the story is told by a narrator, who speaks through characters in the story. In role-playing games, the story is narrated by the DM or GM who speaks through Encounters, and everything that the DM acts out or describes, tells a story, THEREFORE all of the random tables used in the game must be designed by the DM to reflect his world a tell a story.

So, before you stock the dungeon with traps, monsters, and treasure, you must write the encounter tables, from which the random portion of the dungeon will be generated. And then, if the DM makes sense, his or her dungeon will make sense. For example, Let’s take the Goblin Encampment, as I had in my dungeon, there were Goblin Scouts/Foragers, with spears, bows, and leather armor – AC7, rulebook stuff. There were goblin troops with chain mail, shield and sword. There were dire wolves, and wolf riders. I decided that wolf riders would have to be really tough, extrapolating form what we know about wolves, they had to DOMINATE and control the DIRE WOLVES, in order to be able to mount them. So, more hit dice, lower AC due to high dexterity, goblin lances, wee bit less damage than human ones, swords, and bows they can shoot while mounted, in addition, there were hobgoblin bodyguards of the Goblin King, his retinue, and the elite plate mail armored and pole-arm armed Ghoul-Killers, who dealt with the Ghoul infestation in a part of their dungeon, plus the Goblins were bricking off parts of their dungeon for safety and so there were also Goblin laborers. See, hoe the narrative controls the encounter tables that will ultimately stock the dungeon and be the source for the random encounters. But that’s not all. You can have random loot tables, that can give players real insight if they take the time to search the body. These goblins are from some place else. Goblins who live in a rocky pine forest by the cold lake will have different loot than the goblins living in the wind-blown wastelands, dominated by a band of brigands and different from the band of goblins living in a river flood plain different from a band of goblins who serve an evil wizard. I have loot tables that I roll on when players decide to search the bodies, mostly things like socks and tin cups and eating knives, with some chance for a coin and a miniscule chance for an obscure magical item, it could be a +1 dagger, or a magic needle, where the tread never misses an eye of the needle, and there is a chance for the personal possessions that would tell a story: Marked playing cards, ear-rings of the brigands, lengths of rope to carry prized and rare firewood in the badlands, that can also be used for a garrote. Fishing hooks and line for the goblins living near the lake and the river. Waterproof oiled footwear for the ones living on the river, bags with pine nuts for the lake variety, sigil tattoos for the goblins serving the evil wizard. For other dungeons, you should sketch out a basic ecology before designing the encounter tables: Giant mushrooms live in the wet lower caverns. Cave crickets and Fire Beetles feed on them. Tiger beetles prey on the giant insects eating mushrooms. Throw in a Shrieker into the mix, and now you can have an encounter table that will make sense.

Of course, the play is limited by the lack of the imagination on part of the players and the DM’s. The dungeon is the underground labyrinth, the players come to town, go to tavern, buy their equipment, hear rumor about the dungeon, go to dungeon, open the door, kill the monster, take the treasure, go back out. Repeat. People try to overcome, but inevitably, they are limited by their imaginations. Playing caves of chaos in the Keep on the Borderlands with 12 players plus NPC’s, I wanted to build a stockade near the caves, or fortify a farmhouse instead of going back and forth. DM told me that it was impossible to do in a magical world, what humanity since before Ancient Rome did routinely. You create a sandbox, but unless you push the players to deal with it, they will not interact with the fantasy world (so you make them react by making the fantasy world interact with them).

Which brings us to the second question, how real life game differs from the fiction, written as examples of play. The real life interaction is more dysfunctional. There is more die rolling and record keeping and less interaction with the game world. Fantasy gaming is a social ritual, and both players, and the DM’s have their own reasons for playing the game, and the actual adventure takes the second stage to that, which satisfies their emotional needs.

Simply put, D&D is a group activity, like playing poker, like watching the ball game, like shooting pool. If you have a group and it takes up fantasy role playing, it will run better, than bringing together players not connected to each other to play D&D. D&D group will be more dysfunctional, than bringing people together to play chess or scrabble. A D&D group of artistes and intellectuals will tend to pack behavior, but the type A behavior and dominance will be uglier among the D&D players, than among the high school jocks or soldiers, where hierarchies and dominance are in the open and more accepted.

A domineering DM is a stereotype. A psychotic domineering DM is an amusing variation of it. Asocial and anti-social player is another stereotype. They hide their inadequacy under: “I am here to play D&D and not to hang out.”, which is generally a predictor of a poor player. A player with an inferiority complex who wants to build a super tank of a super character really exists. Just as there are rules lawyers, and munchkins, who can’t think outside the box. Passive aggression is common and I have seen a lot of passive aggressiveness and game playing from other areas of life. I have seen psychopathic players straight from juvie spring on an unprepared DM, they went through the motions of rolling up and equipping their characters, and went along long enough to get to the dungeon entrance, when they refused to go in, claiming that their characters are claustrophobic. DM was too inexperienced to handle the situation both, in game, and on the interpersonal level. When they joined my campaign, I quickly figured them out, and had them write a biographic essay describing their player character, they refused, since passing the buck and getting over on others was their thing, and I let them play fighter NPC’s, which they weren’t happy with. They didn’t come back. On the other side of the equation, I had a happy suburbanite, who was comfortable with the traditional D&D ritual. He got uncomfortable at the violence of the tactical combat when the riders caught the players flat-footed in the open, and then he got an adverse emotional reaction, as in he was threatened, by a foul mouthed shield maiden fanatic NPC. He saw a character sheet with a medieval drawing, and I explained to him that the NPC was based on a historical personage, he got weirded out and dropped from the game. Ultimately, there is a comfortable ritual of D&D with a tavern, and a treasure laden dungeon and the magic shop just around the corner, if you have 18 HP you can not get killed by a single arrow that does 1d6 damage. This world is typically limited by the DM’s imagination or lack of it and by lack of the narrative and DMing skills on part of the DM running the game. To this, each player brings his or her own idea of a player character, sometimes with excellent ideas and details, which almost never get integrated into the game world, and then, everyone tags along and works each on their own individual fantasy trip inside their own minds. It is up to the skill and the talent of the DM to overcome this inertia.

[…] trick was to use The Alexandrian’s “Art of the Key” stuff to re-parse the information in a readable fashion. Put […]