When I was first asked to return to my alma mater to direct a play as part of their 2008-2009 season, I started reading plays. And reading plays. And reading plays.

When I was first asked to return to my alma mater to direct a play as part of their 2008-2009 season, I started reading plays. And reading plays. And reading plays.

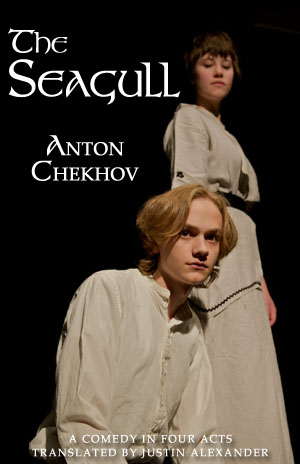

And the play I kept coming back to was The Seagull.

It was a play I had periodically considered producing on my own for several years. It was also an appropriate fit for the technical goals of the program (providing an installed set piece along with period props and costumes). And, given its history with Stanislavski’s acting methods, it was a perfect match with the acting workshops that were being planned as part of the rehearasal process.

So I stopped reading plays and I started reading translations. And reading translations. And reading translations. And reading translations.

This proved to be a much more frustrating process because I wasn’t finding a suitable translation. As a general rule, the translations I read fell into two broad categories:

First, there were the literal and accurate translations. These featured dialog which was as faithful as possible to the original meaning of Chekhov’s Russian. Unfortunately, these were mostly written by Russian scholars, not playwrights. As a result, the English was also stilted and unnatural — lacking the true rhythms of natural speech.

Second, there were the colloquial translations. These sought to make the language flow naturally. (Many of them were written by actual playwrights.) Unfortunately, they tended to achieve this effect by only roughly summarizing or even re-writing Chekhov’s lines.

In the end, I didn’t want to compromise in either direction: I wanted a faithful translation and I wanted natural language that wouldn’t impose an additional barrier to journeyman actors. Eventually I concluded that, if I couldn’t find it, then I would write it myself.

Of course, there was a slight hitch: I don’t actually speak or read Russian.

So I engaged in a process I lovingly refer to as “proxy translation”: I obtained as many different translations of the play as I could and started looking for the intersection. In the end, I worked from the original Russian text, a literal translation mediated through Google’s translation service, and more than fourteen other translations.

Many of the translations I was working from were proxy translations, as well. Some clearly labeled themselves such — like Tom Stoppard’s excellent rendition of the play — while others could be identified through the clearly traceable lineage of certain passages.

I first encountered the art of proxy translation while watching my mother collaborate with John Lewin on a version of Faust that was being workshopped by Garland Wright at the Guthrie Theater. (This project eventually evolved into a full adaptation of the Faust legend into an original play.)

(John Lewin, by the way, was a true master of the art. His proxy translation of Oedipus Rex — which, sadly, has never been published — remains the finest rendition of they play I have ever seen or read.)

It should be noted that proxy translations are sometimes referred to as “adaptations”. While I agree that such translations are distinctly different from those rendered directly from the mother tongue (hence my coining of the term “proxy translation”), I think the use of “adaptation” in this sense is poor terminology. “Adaptation”, in the context of playwrighting and screenwriting, is a term of art and its use here is usually a distortion of what’s actualy being done. Tennessee Williams adapted The Seagull when he re-wrote it as Trigorin’s Notebook. But that’s not what I was doing.

Perhaps the best way to explain the work I did is by example. Here’s a line from the play in the original Russian:

Вы, рутинеры, захватили первенство в искусстве и считаете законным и настоящим лишь то, что делаете вы сами, а остальное вы гнетете и душите! Не признаю я вас! Не признаю ни тебя, ни его!

Tom Stoppard translates this line as: “You hacks and mediocrities have grabbed all the best places for yourselves and you think the kind of art you do is the only kind that counts — anything else you stifle or stamp out. Well, I’m not taken in by any of you! — not by him and not by you either!”

On the other hand, Elisaveta Fen translates it as: “It’s conventional, hide-bound people like you who have grabbed the best places in the arts today, who regard as genuine and legitimate only what you do yourselves. Everything else you have to smother and suppress! I refuse to accept you at your own valuation! I refuse to accept you or him!”

So I look at these and twelve other translations like them, and then I look at my literal translation which reads (in somewhat broken English): “You routiniers have captured the championship positions in art and consider legitimate only that which you do yourself; everything else you yoke and supress! I do not recognize you! I recognize you nor him!”

In this literal translation, I notice two things: First, the odd word “routinier”. Second, the use of the word “yoke”.

So I start with the word “routinier”. I head over to a dictionary and find a definition: “A person who adheres to a routine; especially a competent but uninspired conductor.” The root of the word is clearly similar to that of “routine”, and with a little bit of research I find that similar words are popular expressions throughout continental Europe (particularly eastern Europe). In fact, the Russian word is “rutinier” — it’s literally the same word. But the word is, obviously, not popularly known in English. “Hack” is probably an adequate translation, but what it lacks is that particular sense that they are hacks specifically because they just keep repeating the same things over and over again.

Then I turn my attention to the phrase “yoke and suppress”. This phrase has been various translated as “crush and smother” (Frayn), “smother and suppress” (Fen), “stifle or stamp out” (Stoppard), “sit on and crush” (Hingley), and the like. But in all of these I feel that something is being lost from the sense of “yoke” — the idea of “chaining” or “tying up” other types of work is clear; but there’s also something terrible and evocative about the image of taking young, creative artists and yoking them to your own bankrupt artistic forms (like a great playwright forced to waste his talents on a trite sitcom).

It should also be noted that, although the word is literally translated as “yoke”, in Russian it does carry a specific connotation of “choking” — which is where words like “smother” are coming from in the other translations. The point here is that Chekhov has chosen a word with a rich meaning that simply has no clear analogue in English.

What I eventually rendered out of this conceptual gestalt was this line:

You slaves of routine have seized the premiere positions in the arts, and you only sanction what you do yourselves! Everything else you enslave or suppress! But I don’t acknowledge you! I don’t acknowledge you and I don’t acknowledge him!

The idea of “enslave” is not a precise fit for “yoke”, but it seems to capture the richer sense of Chekhov’s meaning. I lose some sense of the art being “choked”, but I think at least some of that sense of that destruction is still captured in the word “suppress”.

This use of the word “enslave” also resonates strongly with the phrase “slaves of routine”, which I’ve used earlier in the same passage in an effort to capture the meaning of “routinier”.(Before taking this route I actually attempted several versions of the line in which I just used the word “routinier” to achieve a completely literal and accurate translation. Unfortunately, no one had the slightest idea what Kostya was talking about.)

Now, take that same process, repeat it a few hundred times, and you end up with a script.

Of course, this is a rather extreme example featuring two difficult semantic puzzles that needed to be solved. Most of the time the process was the much easier one of simply trying to figure out how to get a particular passage to flow naturally and beautifully off of the tongue.

When I was first asked to return to my alma mater to direct a play as part of their 2008-2009 season, I started reading plays. And reading plays. And reading plays.

When I was first asked to return to my alma mater to direct a play as part of their 2008-2009 season, I started reading plays. And reading plays. And reading plays.