Go to Part 1

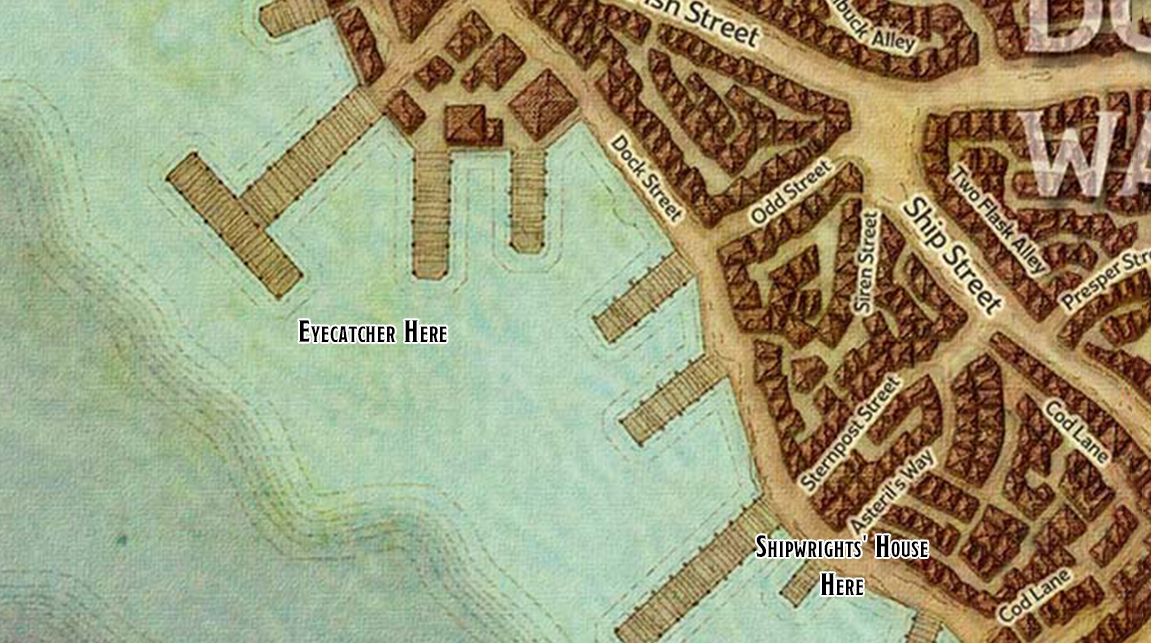

Edana and Theren took the stairs down from the orlop deck to the upper hold of the Eyecatcher. As they rounded the corner to head down to the lower hold where they knew Captain Zord’s quarters were, however, a giant spider dropped down from the ceiling and landed directly on top of Theren’s invisible back.

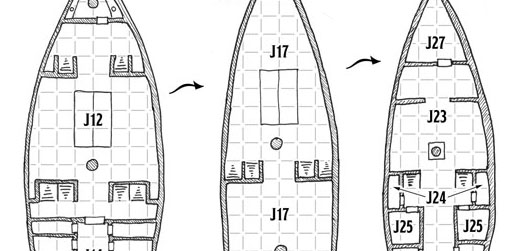

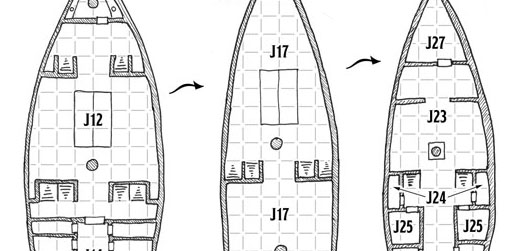

I didn’t see this one coming, either. Running the Eyecatcher from an adversary roster, I saw that there were four giant spiders in Area J17. Flipping open the Monster Manual to the giant spider stat block, I was surprised to discover that 5th Edition had replaced the spider’s tremorsense from previous editions with blindsight.

Cutting here, with the spider on Theren and their stealthy infiltration of the Eyecatcher at risk, is a solid cliffhanger cut. But it also gives me a chance to regroup slightly and quickly review some rules while multitasking the other scene.

Captain Zord rode his polar bear into the midst of the crowd. “The Sea Maiden Faire has arrived!” He twirled a baton high into the air and had the bear catch in his mouth. Behind him, a giant dragon float began a low swoop over the gathered crowd.

“The baton is a little much, don’t you think?” Kittisoth said with scorn.

“What do you mean he’s behind the automatons?” Renaer asked.

And then the whole story poured out: How Captain Zord was selling nimblewrights constructed by the technomancers of Luskan and that the nimblewrights had been outfitted with clairvoyant crystals which would allow Zord to spy on anyone who owned a nimblewright using a specially attuned crystal ball.

Renaer grabbed her hand and began pulling her through the crowd. “Come on!”

Kittisoth grinned. “I’ll bet you knew something like this would happen when you asked me here tonight.”

“It’s always exciting with you, my dear!”

Meanwhile, back on the Eyecatcher, Theren and Edana had managed to fight the spiders off long enough to run down the stairs and into Zord’s cabin, slamming the door shut behind them. The heavy scent of lavender hung thick in the air as the spiders slammed into the door behind them.

The lavender here is a very clever bit of keyed foreshadowing that’s built into Dragon Heist. You’ll see how it pays off in a little bit, and it’s one of the many places in the campaign where Perkins, Haeck, Introcaso, Lee, and Sernett show an excellent attention to detail that truly elevates the material.

Leaving the fair behind them (as Zord, with another wave of his baton, sent a volley of fireworks into the sky), Renaer led Kitti up to a staff-wielding woman in the crowd.

“Kitti, this is Vajra. Vajra, Kitti. Tell her what you told me.”

And the story spilled out again.

This event is being driven from character action, but it’s still taking place within the party planning structure: Vajra is on the guest list. A PC has had an interaction with her. So I put a checkmark next to her name.

As Kitti finished, Vajra furrowed her brow with thought. “If they’re keyed to a crystal ball, do you know where the crystal ball is located?”

“On their ship.”

At this point Edana’s player says, “Dammit, Kitti.”

“Well, I’m already this far in, right?” Kitti’s player says.

When the other players at the table not only start commenting on the action, but having sharp emotional reactions to it, you know things are working well. It may not be immediately obvious, but this is also the payoff from establishing crossovers between the scenes: Edana’s player can immediately see how this thing Kitti is doing is going to eventually snapback and impact her.

“And do you know who currently owns nimblewrights?”

“Oh,” Kittisoth said. “So many people.” And she began to list them: Nobles. Major guilds. Prominent citizens. Vajra’s eyes narrowed.

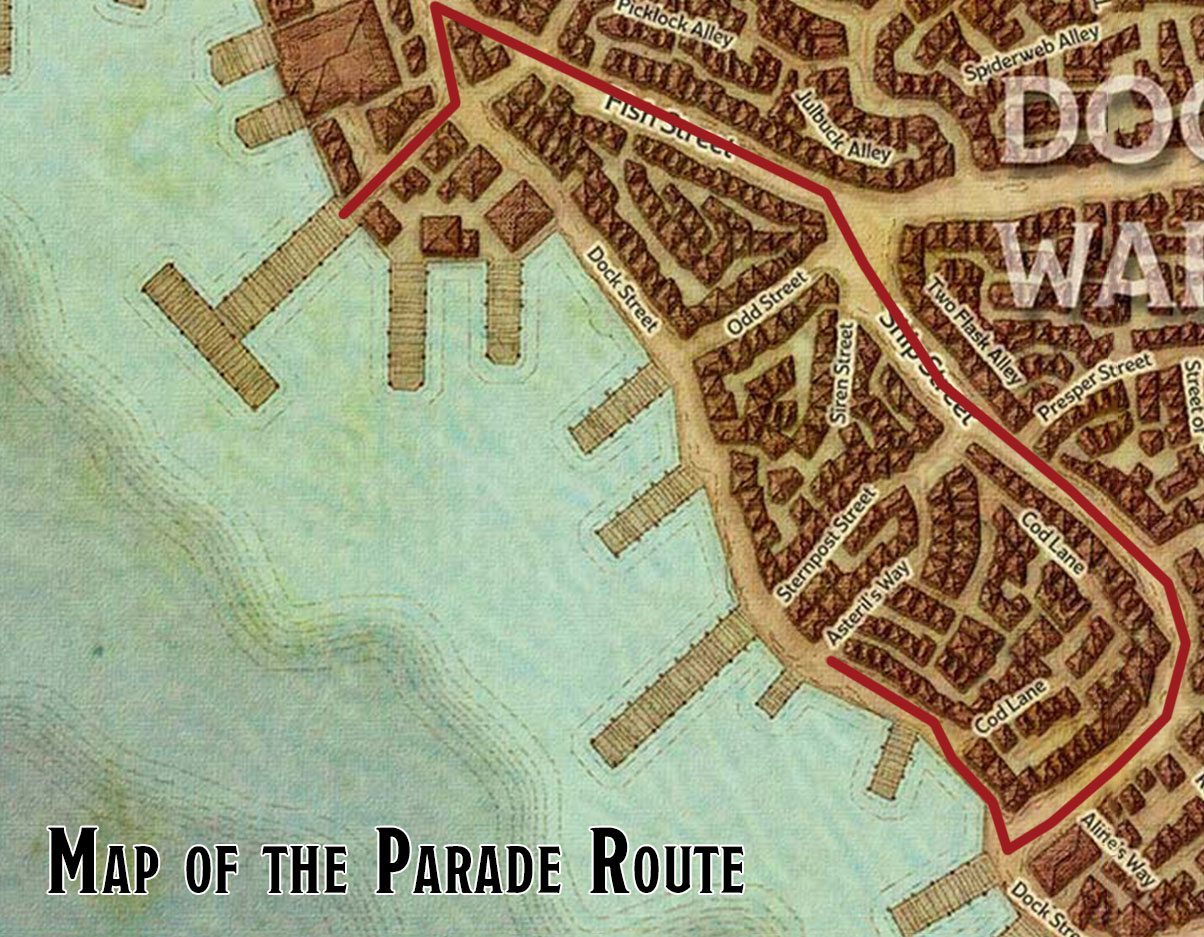

But before they could continue, a man with greased-back hair that tufts up around his ears mounted the stairs of the mansion. As the final volley of fireworks died away, he threw up his hands and announced loudly, “The carnival shall remain here throughout the evening! But for now, it is time for the Grand Promenade to begin!”

Once again I’m actively playing the party structure: I’m looking at my main event list and triggering the next event in sequence.

How do I know the time has come for this to happen? Mostly it’s just dramatic instinct. It felt like enough stuff had happened on the front lawn of the mansion and that it was time for a shift in scenery. From a practical standpoint, it also allowed Vajra to say:

“All right. I need to take my place in this. You get back on Renaer’s arm—” Renaer took Kitti’s arm. “We’ll meet up inside. I need to figure out the damage of… whatever this is.”

Following rules of social etiquette that Kitti didn’t understand, guests began going up the stairs and into the mansion in order of precedence. One of the first was a silver-haired elf in a scintillating blue dress that sparkled with living starlight. Kitti gave a low whistle.

“That’s Laeral Silverhand,” Renaer said. “Open Lord of Waterdeep.”

“Why didn’t you ask her?” Kitti asked.

“She intimidates me.”

“Oh. I get that,” Kitti said. “Yeah.”

And then, surprisingly early in the proceedings, Renaer was pulling her forward, up the grand stairs, and into the cavernous grand ballroom beyond, where the Grand Promenade was circling like a whirlpool into an endless spiral.

At this point I already know what Vajra is going to do, so I’m taking the opportunity of the Grand Promenade to establish who Laeral Silverhand is. That lets the next beat land in the arc that Kittisoth has abruptly transcribed more effectively than if I had waited to introduce Laeral. You can actually see that a bit with the introduction of Vajra: The player doesn’t know she’s the Blackstaff, so her introduction by Renaer doesn’t carry that weight of identity. But now I’ve set it up so that when Kitti actually meets Laeral, both player and character will get the full impact of it.

One thing to note here is that I have NOT put checkmarks next to Laeral’s name. Although Kittisoth has seen her, she hasn’t actually had a meaningful social interaction with her. So she’s still on my To Do list.

While Theren moved a heavy dresser in front of the door to stop the spiders – and anyone else the spiders attracted – from getting in, Edana started looting Zord’s cabin of its valuables.

As she transitioned to scooping up any paperwork that looked useful, Theren whipped back the fur rug on the floor and revealed a hatch they had suspected lay there. Ripping it open, they looked down a short airlock towards a second hatch.

They’d found their entrance to the submersible.

Back at Shipwright’s House, the portly man with the greased hair had mounted a stage at the far end of the room. It turned out that he was Rubino Caswell, the guildmaster. He began giving an. Incredibly. Boring. Speech.

“You have to do this every year?” Kittisoth asked.

As Rubino spoke, however, an incredibly beautiful woman in a dress of yellow silk glided over to Kittisoth and leaned down to whisper in her ear. “Is this a good place to talk about an ‘explosive’ matter?”

Kittisoth glanced at her. “No. I don’t think so.”

“Then come with your comrades — your other comrades — to our villa tomorrow morning for a more… discrete discussion.”

And the woman glided away.

Renaer leaned in. “What was that all about?”

“She seems to know something about our investigation into the explosion that killed Dalakhar,” Kitti said.

Renaer frowned. “Be careful around the Cassalanters,” he warned her. That was useful. Kittisoth wouldn’t have had a clue who the woman was otherwise.

This is somewhat unusual: With Rubino’s Speech and the Cassalanters’ Approach, I am very rapidly triggering events from the main event track. Much more rapidly than I normally would. (Generally speaking, you’ll trigger an event and then let all kinds of social eddies and currents spin out from that before shaking up the status quo again with the next event.)

Why?

Because Kitti has initiated a sequence of actions here which I know is going to yank her completely off the main event track I had designed for the evening. I wasn’t entirely certain how the next scene would end, but it was quite possible it would derail the party entirely. The Cassalanters’ Approach was included as an essential hook that would come one way or another (even if Kitti had skipped the party entirely, the Cassalanters would have sought the group out through some other channel), so I wanted to drop that invitation now before the next scene took place and I potentially lost the opportunity.

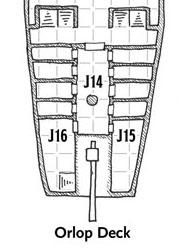

Meanwhile, Theren and Edana clambered down through the airlock and into the submersible. Passing by the engine room carried them out to a main passageway: At the far end of it they could see that the front of the ship opened up into a sort of bulbous, multi-level control room. The walls of the control room were large, globular windows looking out into the blackwaters of Waterdeep Harbor.

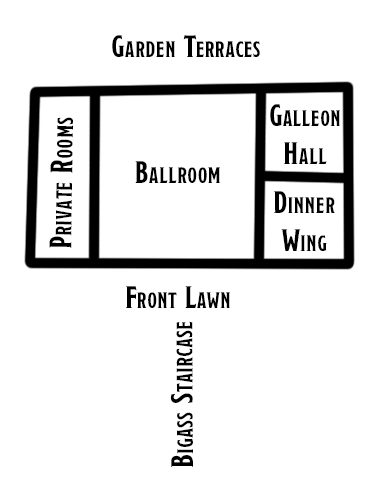

CUT TO: Rubino was finally finishing his speech and the crowd was beginning to form little social clusters that either drifted through the ballroom or made their way back out towards the carnival displays that the Sea Maidens Faire had rapidly erected. Renaer and Kittisoth made their way through a bramble of social introductions, trying to figure out where Vajra had gotten to. They eventually spotted her opening the door to a small, private room off to one side of the ball room.

Nothing too fancy here: The same way that we’ve been looking at our guest list and main event list, I’m now looking at the zones I’ve sketched out on my location map and picking one for the next scene.

They rushed over to Vajra and through the door. Kitti was looking back over her shoulder, scanning the crowd as she entered. As Vajra shut the door behind them, she turned around and–

Standing right in front of her was Laeral Silverhand.

Oh no.

The, “Oh no,” of course, was actually spoken out loud by Kitti’s player at the table. A character’s inner monologue becoming manifest through a player’s meta-commentary on what’s happening can be really great.

“All right,” Laeral said. “What is this all about?”

And Kitti’s player said, “I tell her the thing about the thing that I’ve been telling everybody all night with my big fucking mouth.”

As she finished, Laeral said, “Bring me Captain Zord. Right. Now.” And her eyes sparked with tiny shards of blue lightning.

“Oh. Oh no,” Kittisoth babbled. “I don’t think that’s such a good idea right now, is it?”

Laeral smiled as her guard hurried out of the room. “I promise you we will not make too much of a scene.”

CUT TO: Theren and Edana cautiously made their way down the passageway and looked down into the lower level of the control room. Several gnome tinkerers were at work there, apparently overseen in their work by… a dark elf. That was no good. They cautiously backed up.

The motivation for the cut to Theren and Edana here is probably pretty obvious: The appearance of Laeral had cranked the stakes way up. Reading the room, it was clear that everyone was completely on tenterhooks waiting to see what would happen. So you cut away. You let them live in that moment for a bit.

Laeral took a seat on the far side of the room. “So who is this, Renaer?”

“I’m not really anybody,” Kittisoth demurred.

“I doubt that’s true,” Laeral said with a smirk, looking at the way Renaer’s hand was resting on Kitti’s arm.

“I’m sorry,” Kitti said. “I don’t know what to say. You’re very intimidating.”

Laeral smiled and took Kitti’s hand. “It’s all right. Everything is going to be fine. We appreciate all the hard work you’ve been doing on behalf of Waterdeep. Please, step over here for just a moment.” She reached out into midair and her hand disappeared into some sort of dimensional pocket; a moment later she drew back a decanter of brandy.

“What’s our play here?” Vajra asked while Laeral poured.

“I like shock and awe,” Laeral said. “We’re going to talk to ‘Captain Zord’ and find out exactly what game he’s playing here.”

The handle turned and the door began to open–

CUT TO:

The table literally shrieked in frustration here. Yeah. That’s when you’re doing it right. You can’t force this sort of thing and you don’t want to overplay your hand, but when the anticipation is building sharp, quick cuts will heighten it even further, so that when the moment arrives it lands with even more power.

Faced with several doors, Theren and Edana picked one at random.

At this point I asked, “Exactly how do you open the door?” This prompted them to detail with great care and specificity exactly what precautions they were taking.

This was actually irrelevant for this particular door, but it would have been relevant for any other door they had picked in that passageway. (They got very lucky with their random pick. It would be the last luck they would have for awhile.) By asking them the question regardless I (a) remove metagame anticipation if I need to ask the question for future doors (“he already asked and it wasn’t relevant, so we know this is just a routine question he asks”) and (b) build a moment of suspense that pays off even if there isn’t an ambush on the other side of the door.

As they very gently eased open the door… the scent of lavender washed over them.

And here’s the lavender scent pay-off. The players take a great deal of satisfaction in the simple act of concluding that this room must also belong to Zord.

The crystal ball was sitting on a padded cushion of black velvet on a pedestal in the middle of the cabin. They scooped it up and dropped it into their sack.

CUT BACK TO: The door opened.

Captain Zord, flanked by the two watchmen, entered the room. The watchmen remained outside, closing the door behind him.

Zord swept the hat from his head and bowed deep. “Milady Silverhand, how may I be of assistance to you?”

Laeral gave a silent hand signal to Vajra. Vajra pointed her staff at him. There was a brief purple pulse from the end of the staff and Zord’s disguise spell melted away, revealing a dark elf.

At this point, my plan was to dramatically reveal Jarlaxle’s picture. But I actually fumbled retrieving the picture and wasn’t able to cleanly display it.

That was all right, though, because the lore-steeped players at my table had gotten ahead of me and did the work for me: “It’s Jarlaxle,” says one of them. “Oh no!” cries another. A third has dim memories of the Drizzt novels she read in her youth stirred up at the name.

This is pure RPG as an audience: None of the characters know who Jarlaxle is, so this is all firewalled away. But as players, they are all on the edge of their seats and completely engaged and BAM one last amazing revelation has them amped up about as high as they can possibly go.

Laeral spoke. “Jarlaxle. What do you think you’re doing?”

Jarlaxle’s eyes widened in mock innocence. “Milady, whatever do you mean?”

“Crystal balls. Nimblewrights. Explain yourself.”

“I see.” Jarlaxle was taken aback. He clearly wasn’t used to it. His eyes darted around the room, quickly taking in who was standing there. “Well… milady… as I have written to you often — and I am so glad that you have granted me an audience this evening! — my interests are simply to gain your support in seeing Luskan given its proper place in the Lords’ Alliance.”

“Do you really think that spying on me and—”

“Ah! I never spied on you! You did not receive an invitation to purchase a nimblewright, and I have taken special efforts to keep them away from you,” Jarlaxle said. “They were merely employed as an information-gathering service. And I can assure you that if any information I had obtained were to indicate a threat to Waterdeep, I would have surely—”

Laeral raised her hand to cut him off. “Jarlaxle, your tongue is as nimble and sweet as I remember. But I am not to be gulled.”

“I was attempting to gain blackmail material to further my cause as the Lord of Luskan,” Jarlaxle said plainly. “As any Lord of a City-State of the Sword Coast has an obligation to do. You yourself, I believe, employed similar tactics with your husband Khelben Arunsun on many an occasion.”

Talking to yourself as the GM is really hard to do, but having distinct characters with clear, conflicting objectives helps a lot. And when you can pull it off well it’s worth it. This moment got an audible, “Ooooo…” from the table as Jarlaxle scored a palpable hit, which was a good indication that it was time to…

CUT TO: Theren and Edana weren’t certain they could make it back through the Eyecatcher and escape. There was no telling what sort of alarm had been raised by the giant spiders they’d left behind.

They decided that their best option was to disconnect the submersible from the Eyecatcher and then swim out of the airlock. They decided that they might as well try to sink the submersible, as well, having no idea what mischief Captain Zord and the Luskans meant to use it for.

But when they opened the hatches, they discovered there was an energy field preventing the ship from flooding. “The only way this is going to work,” Theren said, “is to disable this field from the control room.”

So they snuck back down the hall together. Edana used a mage hand to reach out, grasp the lever, and—

CUT TO:

“Do you know what we do with traitorous captains in the Pirate Isles?” Kittisoth asked the room.

“I don’t,” Laeral said. “What do you do in the Pirate Isles?”

“We tie ‘em to the main mast and wait for the vultures to feast,” Kitti said.

Jarlaxle glowered at her.

“There’s interesting,” Laersal said. “I think he owns a vulture.”

“He owns a lot of sad animals,” Kittisoth said. “Just like himself. I’m sorry. I’m just sharing information. I know you’ve got this well in hand, milady.”

“I like this one, Renaer,” Laeral said. “You should keep her.”

“You can’t call me a traitor!” Jarlaxle protested. “I am not a citizen of Waterdeep. I’m a Luskan patriot.”

“I’m sorry,” Kittisoth said. “The women are talking.”

Another cool thing about this kind of scene-juggling is that it doesn’t just give you, as the GM, a chance to gather your thoughts: It also gives your players a chance to think about what their next course of action (or clever turn of phrase) will be.

Jarlaxle opened his mouth to respond, but then got a distracted look. “What are you doing, Laeral? My ships are under attack!”

Note here that Jarlaxle is basically anticipating something that hasn’t actually happened yet to the other group: He’s responding to the events that play out after Edana pulls that lever. This is a more advanced crossover technique, where you effectively foreshadow what’s going to happen to the other scene before they actually see it for themselves.

Edana pulled the lever.

Water came gushing down the passage behind them. Edana and Theren both grabbed handholds on the walls. As the water ripped into them, Edana kept her grip, but Theren couldn’t. The deluge swept him down the hall, over the railing, and slammed him down onto the deck of the control room, amidst the gnomes and the drow.

With the water still pouring down from above, Theren tried to swim out. But one of the gnomes either heard him or saw his invisible outline in the water. “Someone’s here!”

The drow waved his hand and everything in the control room was suddenly limned with the dancing green flames of faerie fire… including Theren. He surged to his feet to make a run for it, but one of the gnomes lowered his hand and—

After rolling so well all evening, the dice really turned on Theren here. After failing multiple checks to not get gushed into the control room, he now rolled a natural 1 on his saving throw vs. the burning hands spell and then I rolled max damage on 3d6. He only had 16 hit points left and so—

—the flames washed over his chest, blasting him off his feet. Blackness gripped his vision as he splashed back into the water, unconscious and at the mercy of the drow.

And that’s when I called it for the night. Always leave ’em wanting more.

and several others I had already planned on introducing in the near future (Vajra, the Cassalanters). The only new character was the guildmaster.

and several others I had already planned on introducing in the near future (Vajra, the Cassalanters). The only new character was the guildmaster.