IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

As Dominic finished, his eyes blazed with silver light. Rehobath was entranced. “It is the mark… It’s hard to believe that one of the Chosen should have come to me.”

This meeting between Dominic and Rehobath is a major turning point in the campaign.

Looking back on this moment now, it’s hard for me to imagine a version of In the Shadow of the Spire in which this doesn’t happen. But the truth is that if I ran this campaign another fifty times, the chances of this – or anything like it – happening again are basically nonexistent. Like “The Tale of Itarek,” this moment, and everything that comes from it, is the result of completely unanticipated player decisions building one atop another.

(If I actually did run this campaign again, of course, I might choose to restructure it to make including this material more likely. This is not out of the question. For example, the Severn Valley scenario I designed for Eternal Lies was similarly the unplanned result of very specific and relatively unlikely decisions made by the PCs. When I ran the campaign a second time, however, I added specific clues to make it more likely that the PCs would end up going there.)

So let’s take a moment to talk about how we got here. I think you’ll find it interesting, at least in part, because it also demonstrates how a number of different techniques I’ve discussed here at the Alexandrian can combine together in actual play.

Unlike most of these Running the Campaign essays, this one will contain SPOILERS for upcoming installments of the campaign journal. So you may want to skip it if you’d rather be surprised.

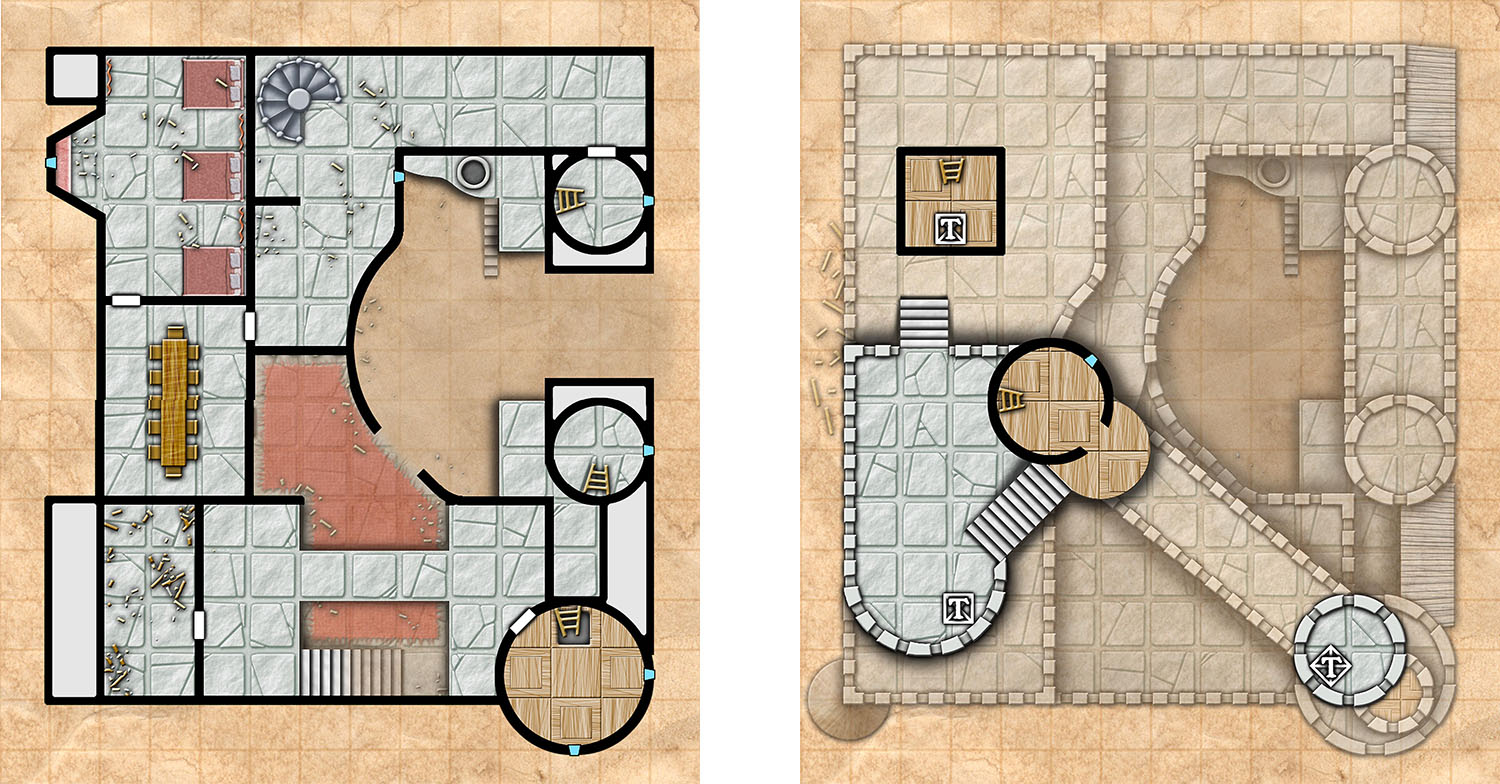

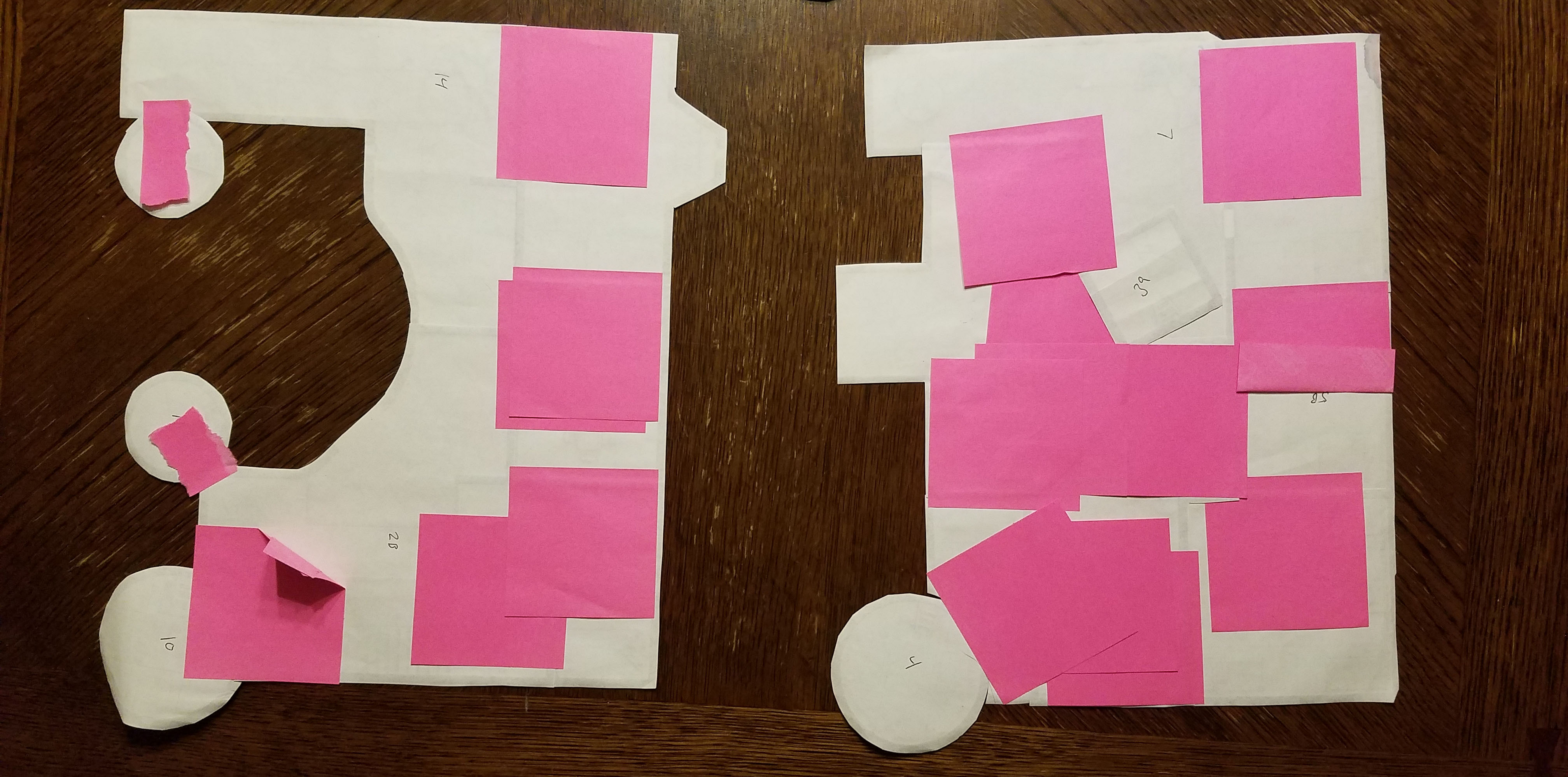

STAGE 1: ACTUAL PREP

In terms of actual prep (i.e., things I planned as the DM), there are basically two points of origin.

First, Dominic’s eyes. These were included in the campaign as one of the clues to the metaplot mystery of what had happened to them during the period of amnesia immediately preceding the beginning of the campaign. The notes describing the eyes were quite brief:

- If Dominic praises Vehthyl while wearing or holding the mithril holy symbol he woke with, his eyes become glowing silver globes with the following effects: +2 to Spot checks, detect magic, can be active for up to 15 minutes per level per day.

- A Knowledge (religion) check (DC 22) reveals that this is one of Vehthyl’s signs – it is a mark of the god’s chosen, indicating that they have taken the first step on the path to sainthood.

Second, Rehobath and his relationship with the Imperial Church. This gets a little more complicated.

Rehobath is based on Monte Cook’s Rehoboth. In the original Ptolus setting, Rehoboth Ylestos was the Emperor of the Church. When the Empire fell, Rehoboth fled to Ptolus, where his son Kirian Ylestos was the Prince of the Church, and “declared himself secular Emperor as well as the head of the Church of Lothian and set up his own Imperial court in the Holy Palace.”

Because I was transplanting Ptolus into my own campaign world, I had to figure out how to adapt that to fit with the gods, religions, and politics of the Five Empires. This went through several iterations, some of which were quite convoluted. (At one point, Rehoboth was theoretically being held in religious asylum and seclusion by his son, but the two of them were secretly working together as a nefarious conspiracy.) But at the time the campaign started it had settled into a more basic form:

- Rehobath (note the subtle name change, which I’m definitely claiming was deliberate and not a typo that iteratively asserted itself into all of my campaign notes) had once been the Gold Fatar of the Inner Cathedral of Athor. In the political wrangling around the appointment of the last Novarch (the head of the Imperial Church), he was effectively demoted to being the Silver Fatar of the Outer Cathedral of Athor in Ptolus.

- Aggrieved in his new position, Rehobath gathered power and eventually declared himself both the Novarch-in-Exile and Holy Emperor, claiming divine right of rule over both the Imperial Church and the Empire of Seyrun.

- Kirian Ylestos (who was no longer Rehobath’s son) had been sent by the Imperial Church to replace the heretic Rehobath as the rightful Silver Fatar of the Outer Church of Athor. He was successful in ousting Rehobath, who took up residence in the “Holy Palace” in the Nobles’ District.

Shortly after the campaign started, however, I realized that I’d made a mistake: It would be far more interesting to rewind the timeline and include all of that political finagling as backdrop events that would play out as current events in the Ptolus newssheets while the PCs went about their adventures.

So, at this point, Rehobath was still the Silver Fatar of the Outer Cathedral, although he was actively scheming to declare himself Novarch-in-Exile.

STAGE 2: PLAYER INTEREST

Once Dominic discovered that his eyes glowed silver whenever he praised Vehthyl, he became interested in figuring out why. Although it seems fairly obvious in retrospect, I had not anticipated that his interest would take the form of seeking out local Vehthylian religious experts.

I’ve previously discussed the method I used to respond to his interest in “An Interstice of Factions,” so you can check that out at length. But what it boils down to is that I gave him four different options:

When Dominic headed across the bridge into the Temple District, he made gentle inquiries into the worship of Vehthyl and discovered four options: First, the Order of the Silver God. Second, the Temple of the Clockwork God. Third, the Temple of the Ebon Hand. And, finally, an itinerant minotaur priest named Shibata.

This list was largely prepped by simply going through my notes and seeing which religious organizations and individuals in Ptolus were associated with Vehthyl. Although the Order of the Silver God (part of the Imperial Church) is included in this list, you might notice that Rehobath and his politics still aren’t present.

STAGE 3: UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

At Harvesttime, Dominic chose to speak with Shibata. He got some guidance and insight into what it means to be Chosen by one of the Nine Gods and what the religious mystery of Vehthyl was, but he ultimately wasn’t satisfied with the answers he got. So after mulling things over for a bit, in Session 14 he decided to seek more guidance at the Temple of the Clockwork God.

This actually came a bit out of left field for me as a GM: After seeking out Shibata, I hadn’t realized that Dominic was still thinking about looking for more answers, so I had never given any meaningful thought to what would happen if he went to the Temple of the Clockwork God. So I stalled:

The priest shook his head. “Why this should be or what your purpose is, I cannot say. And the wisest among us are not here. We would like to wait for their return and then pray for the guidance of Vehthyl. Can you return to us? Let us say in five days time, upon the ninth of Kadal?”

Basically, the five days of in-game time would give me some time to prep content that would meaningfully reward Dominic for pursuing this avenue of investigation. I knew that the Temple of the Clockwork God and another organization known as the Shuul were loosely aligned and that both of them venerated the Iron Angels. The Iron Angels are basically ancient fantasy mecha that were somehow related to the Lithuin Titans, and various ruined Iron Angels had been recovered in archaeological digs in recent years. (This is because Cook had used the name “Iron Angel” to refer to neutral outsiders related to the Iron God, but my setting already used that name for the ancient constructs and rather than giving the Iron Angels revered by the Shuul a new name, I decided it would be more interesting to have them simply revere my existing Iron Angels.) I knew that the Shuul had been reconstructing one of these Angels, and they and the Temple of the Clockwork God were interested in figuring out how to revive it (basically bringing what they perceived as a dead god back to life). I decided that Maeda, the head priestess of the Temple of the Clockwork God, would perceive the coming of the Chosen of Vehthyl as a sign that the time for reviving the Iron God had come.

I hadn’t done much more than put together a few fragmentary notes to this effect, however, when, as I discussed in Session 19, the group’s actions unexpectedly caused them to raid the Shuul’s headquarters. Given the timeline involved, it made sense that Maeda’s communications with Savane, the head of the Shuul, would be there and the PCs discovered it:

Brother Savane—

Brother Tannock has brought me strange news. A man bearing the Mark of Vehthyl has come to our temple. He is to return to us on the 9th of Kadal, at which time I shall see for myself. But if the Chosen of Vehthyl has come to us, then the hour has arrived. Can the Iron Angel be made ready?

Maeda

When I wrote the note, however, I hadn’t anticipated that the PCs would interpret it in the worst light possible. I thought it would be kind of a cool, enigmatic reference to the “Iron Angel” and then, when Dominic met with Maeda, there’d be a payoff when Maeda revealed what the Iron Angels were. (“Make it a mystery” is a technique described in Random GM Tips: Getting Players to Care.)

Instead, the note scared them: The Temple of the Clockwork God were conspiring with the Shuul and clearly had some sort of nefarious agenda where Dominic was concerned. Dominic resolved to skip his appointment with the Temple and was left figuring out where he wanted to turn next for answers.

STAGE 4: UNANTICIPATED CHOICE

At this point you might anticipate that Dominic would choose between one of the two remaining options he had found at Harvesttime: The Order of the Silver God or the Temple of the Ebon Hand.

Instead, he did something completely unanticipated: They had been briefly introduced to Rehobath during the Harvesttime celebrations at Castle Shard, and they made the decision to reach out to him directly as the local head of the Imperial Church.

So… what happens?

Well, I look at what I know about Rehobath and his agenda. And then I think about what he would do if the Chosen of Vehthyl basically fell into his lap.

The result, of course, is that the PCs are going to be thrust directly into the middle of Rehobath declaring himself the True Novarch of the Imperial Church.

And then things get even crazier.