DISCUSSING

In the Shadow of the Spire – Session 27B: Sights of Venom

Ranthir used his more powerful spell of clairvoyance to peer into the room… and there, standing in the midst of wrecked furniture and miscellaneous debris, he saw two massive, insectoid creatures.

At the sight, he blanched.

As he watched, one of the creatures reached out with its sharp talon and literally drilled the still-drafting curtain into the wall, pinning it in place.

In our last installment of Running the Campaign, we talked about what happens when the PCs miss clues. That actually continues into this section of the session: The project site (i.e., the apartment building controlled by cultists) had been prepped using status quo design. That meant that everything inside the building was basically held in a state of plausible stasis up until the point that the PCs interacted with it.

Once Ranthir cast his clairvoyance spells, therefore, and peeked inside, that status quo was disrupted and events started playing out. One of those events was the argument between members of the Ebon Hand and the Brotherhood of Venom. My anticipation had been that some very important information would get dropped during this conversation (i.e., clues), but because Ranthir was (a) using a spell which only granted sight, not sound; and (b) he couldn’t read lips worth a damn, most of that information was forever lost.

(Well, until the PCs gained it in a different way. Three Clue Rule and all that.)

As you’ll see in future sessions, the decision here to briefly engage the project site (setting events in motion) and then almost immediately withdrawing (“Let’s get out of here.”) had a significant impact on how subsequent events would play out.

But there was also something else the PCs did here that I didn’t expect:

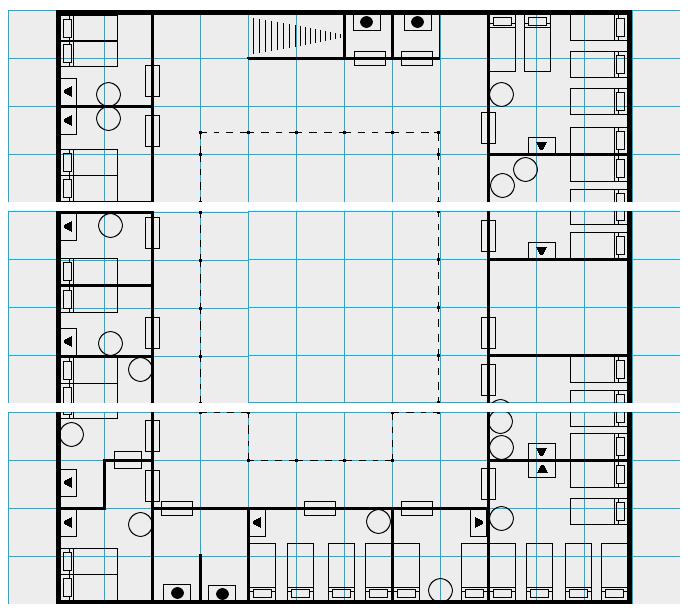

The apartment building being used by the cultists was one of several similar buildings lining Crossing Street. Since Ranthir would only be able to target two specific locations with his spells, they decided to scout out the other buildings to get a better sense of what the layout might be like inside the cult’s building.

This tactic emerged because I have a giant, 8-foot-long map of Ptolus hanging on my wall during sessions, which meant that the players could see exactly what these buildings looked like:

But such a moment could easily arise in any number of ways. The key point here is that the PCs unexpectedly went into a building I had not anticipated them going into.

Now what?

This, of course, is exactly why so many video games nail the doors shut on all the buildings in town.

IN THIS CASE…

In this case, the players’ proposed reason for going into the building conveniently gave me the solution: They hypothesized that the neighboring apartment buildings, although slightly different in size, would have similar floorplans to the project site. I had floorplans for the project site, so it was relatively easy for me to just use those floorplans as the basis for some quick improvisation.

This exact scenario probably won’t crop up that often for you, but the general principle can be more broadly applied: Grab a floorplan you already have prepped — from the current session or perhaps from a previous session — and use it.

Just like these apartment buildings, the similarity of the buildings can be quite diegetic: The world is filled with structures built to a common floorplan.

MAKE IT UP

Obviously the easiest thing for me to say is, “Just make it up.”

Easy to say and great if it works. But improvisation takes practice and, honestly, no matter how much practice you get, there’ll still be times when you come up dry. That’s what the rest of this article is for.

But before we dive into that stuff, a quick word about making it up: Don’t feel like the whole building needs to spring full-blown from your brow like Athena doing Doric cosplay. You can build it up over time, describing only what the PCs need to know at any given moment. As play proceeds, a sketchy understanding of the building will start filling in with details.

A few thoughts on this:

- The first thing you’re likely to need is the exterior of the building. What’s the first thing that pops into you head when you think of the building? Describe that.

- If it’s a tactical situation, a key thing here will be entrances (do more than one) and windows.

- The second thing is to think about why the PCs are interested in the building: They’ll have probably already told you. (They’re looking for the CEO’s office. Or they’re trying to get to the roof. Or they want to hack the mainframe.) Roughly speaking, where is that stuff? First floor? Basement? Top floor?

- Once they pick an entrance, describe the lobby or front room or kitchen or whatever it is they see when they go through that door.

- Once again, think about where the exits are and start getting a sketchy feeling for where they might lead (with some thought for how they might connect to the PCs’ goals).

And then proceed along those lines.

But it also doesn’t have to be that complicated!

It’s very often true that you don’t actually need a floorplan at all.

For example, if the PCs have come here to meet with the CEO, you don’t need to know the whole building. In fact, you can probably just cut straight to a scene in the CEO’s office.

On the other hand, if you do need a floorplan and you need it right now (it’s a tactical situation, you’re playing with a VTT, etc.), then you can…

GOOGLE IT

Just hit up a search engine and type in whatever building type you’re looking for plus “blueprints” or “floorplans.”

This tends to work most reliably with modern buildings, but adding “fantasy” or “science fiction” to the search can often pull up what you need. (More reliably with the former than the latter.) These days if you add “RPG,” too, you’re likely to get a full-blown battlemap more often than not.

BUILD YOUR STOCK

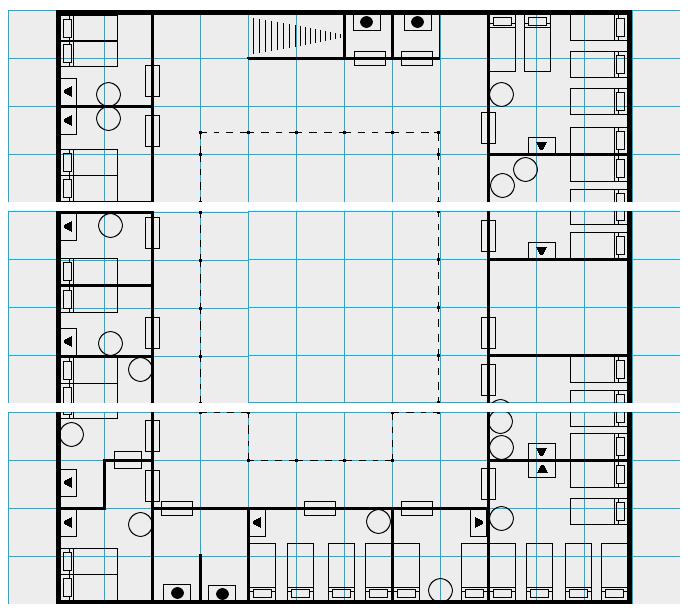

Instead of scrambling with image searches at the table, you can get ahead of the game by building up a supply of stock floorplans for common locations.

- 4 or 5 different houses

- 2 or 3 warehouses

- 3 or 4 offices buildings

- A shopping mall

That sort of thing.

You can make a big push to assemble this in a marathon prep session, but it’s also something you can slowly build up over time: When you prep an adventure with a house, for example, tuck the floorplan for that house into the accordion folder or computer directory where you’re keeping your generic stock of floorplans. Over time you’ll just sort of accrete what you need.

Either way, you’ll slowly develop a sense of exactly what type of floorplans you’re likely to need, and that knowledge can often transfer from one setting to another. (As can many of the floorplans, in fact. Particularly if they don’t need to be seen by the players.)

RANDOM FLOORPLANS

Another option is to use a random generator to create the floorplan you need on-the-fly.

If you poke around a bit, you can find a number of online generators, like this Random Inn Generator from Inkwell Ideas. Collect these links in your digital notes and you can get something like this with the press of a button:

Personally, I prefer a more generic generator that I can use with just dice-and-paper. You can find the tool I use in my article on Streetcrawling Tools. It provides enough of a scaffold that I can iterate the rest, but is generic enough that I generally only need the one tool. That way I don’t feel overwhelmed hunting for precisely the right tool if my stock of generic floorplans doesn’t have exactly what I’m looking for.

It’s sort of the multitool of, “Oh crap, my players just went into a random building!”

NEXT:

Campaign Journal: Session 27C – Running the Campaign: Playing to the Crowd

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index