SESSION 36B: THE MADNESS OF MAHDOTH

January 24th, 2009

The 19th Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

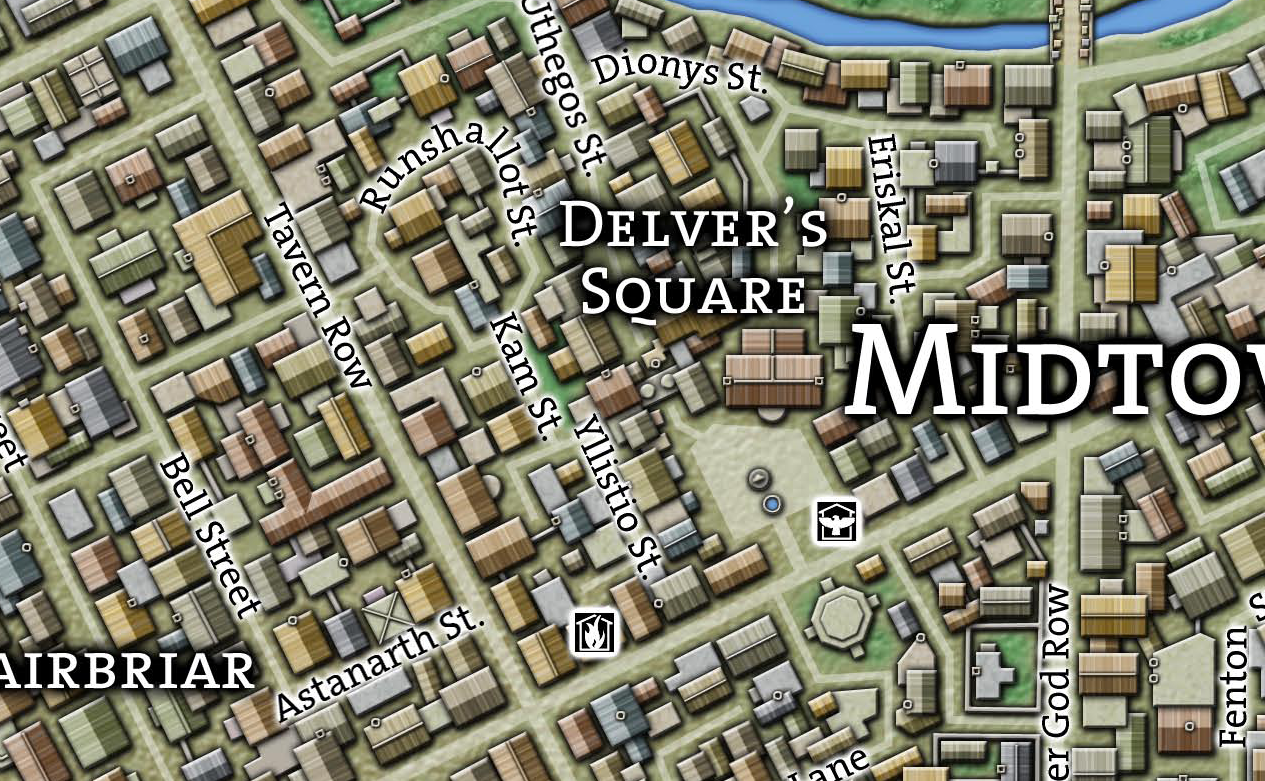

Leaving Castle Shard, they headed down into South Market. There they found Mahdoth’s Asylum – a small, rather nondescript building on Childseye Street.

They were greeted in the small, rather dingy offices of the asylum by a plain-faced, brown-haired man who introduced himself as Danneth Sonnell.

“Ah… I believe you sent me a letter, sir,” Ranthir said with a slight smile.

“And you are, sir?”

“Master Ranthir.”

“Ah, of course. Yes. I am glad that you have come.”

Danneth led them down a back stair into a basement of remarkable size. Not only its scope, but the stonework of its construction was quite out of keeping with the plain wooden construction above. (It had almost certainly been repurposed from some older structure.) They were taken through several rooms and then into a long hall lined with iron-doored cells.

Halfway down this hall a figure suddenly threw himself against the bars of the nearest door: “Please! Get them out of here! Get them out! They’re driving me mad!”

Danneth quickly crossed to the door and shut the outer shutter, but not before they had recognized the prisoner as the dwarf who had been summoning fell creatures during Tavan Zith’s escapade through Oldtown.

At the end of the hall they turned into another, similarly lined with cells. Danneth led them to one of the doors along this hall, removed a large ring of keys from his belt, and unlocked it.

“What exactly do you want us to do?” Tee asked.

“I honestly don’t know,” Danneth said. “When he is not asking for Master Ranthir he simply raves.”

“What’s his name?”

“Tabaen Farsong, an elf of House Erthuo.”

They exchanged glances and shrugs. None of them recognized the name.

Danneth opened the door. Crouched against the far side of the cell, feebly pawing at the wall and murmuring inarticulately under his breath, was a scrawny figure dressed in shabby clothes. As the inmate looked up they saw that it was another of Tavan Zith’s victims: The elf who had been driven mad during the ordeal.

Tabaen’s eyes seemed drawn to Ranthir’s, locking his gaze upon the mage. He said in a desperate, sibilant whisper: “A key. A noble key. You know the door. The key is the hand which will open the door. You have to get it. You have to get in to keep them out. A key which is a hand and a staff which is a knife. Many dangers. So many evils!”

The words poured out of his mouth, but as soon as they were done the elf’s eyes emptied of thought and he sank back against the wall.

Danneth rushed to his side and quickly examined him. “There’s no response.”

“He’s comatose?” Dominic asked.

Danneth nodded.

“I’m sorry,” Ranthir said, sincerely abashed.

Danneth shook his head. “I don’t know. This might be for the best. At least his mind is at rest.”

“They’re here master!”

The sudden cry had come from the far end of the hall. Looking that way they saw a dark-haired halfling peering around the corner.

There was a moment of puzzlement and then, floating into view from around the corner, came a beholder.

“What’s happening here?” The beholder’s voice was gruff and impatient. “Who are you? What are you doing here?”

“We were summoned,” Tee said brashly. “Who are you?”

“My name is Mahdoth. This is my asylum. You are not welcome here.”

Danneth emerged from the cell.

“Master, I—“

“I told you that there were to be no visitors here.”

Danneth fell silent.

Mahdoth turned to the rest of them. “Leave. Now.”

Tee walked up to him. “You’re being very rude. We were asked to be here.”

Mahdoth glowered down at her with his large eye. “Danneth should not have brought you here.”

“That’s between you and him.”

“Zairic, show them out.”

The obsequious halfling scuttled forward and escorted them out of the complex. As they walked down the street away from Mahdoth’s, they chatted briefly about the encounter.

“Do you think he was hiding something?” Ranthir asked.

“I’m sure of it,” Tee said. “On one of his eye-stalks he was wearing a bone ring.”

THE ALL-KEY AND THE CODEX

When they returned to the mansion on Nibeck Street, they found Elestra waiting for them. they ran through the now familiar checklist of unanswered questions and tasks left uncompleted. But this time their conversation returned to the strange, obsidian box that Ranthir had found in his rooms upon awaking for the first time at the Ghostly Minstrel.

“I really want to know what’s in there,” Tee said.

“Maybe it’s a magic box. Maybe our memories are trapped inside,” Ranthir said, only half-joking. “We just open the box and we get our memories back.”

But wishing the box open wouldn’t make it happen…

… unless they’d been over-looking the solution.

“What about the key from Pythoness House?” Tor asked. “The one that can open any lock?”

“Would that work?” Tee asked. “There were no moving parts in the lock.”

Ranthir shrugged. “I don’t know. It might.”

And so, quite unexpectedly, they turned towards the Hammersong Vaults. There Tee removed the golden key from her lockbox (immediately feeling the heavy weight of its soul-wearying effect) and Ranthir retrieved the obsidian box from his. They returned with both of them to the Banewarrens and rendezvoused with Elestra. They quickly explained their plan to her.

“That might be why we were looking for they key in the first place!” Elestra exclaimed.

“Here goes nothing,” Tee said. She slipped the key into the feature-less lock of the obsidian box.

It turned effortlessly.

Tee felt the strength of her soul pulled through the key and into the lock. In the same instant, a thin sliver of light spread along the box’s impenetrable seam. A moment later the lid popped open with a burst of stale air.

FLASHBACKS

In that moment, Tee found her vision turned inward: There was an echoing, thundering crash… and she found herself stepping through a wall of broken stone and shattered shards of adamantine. Beyond it, in a small vault of sorts, there stood only two columns of stone. And atop each column was a solid block of obsidian, gleaming with a faint iridescence. And a voice spoke: “At last! The secrets of the Stonemages!”

Ranthir found himself sitting in an inn’s common room, hunched over a table. A fire roared a few feet away. He was speaking to an older man, with white hair and a well-trimmed beard. “I’ve found it. It’s being carried by a northern barbarian and an elven girl.”

Dominic and Elestra once again found themselves standing before the door of shadows upon the cliff-wall of the Northern Pass.

And, Agnarr, too found his thoughts cast back to the interior of a black coach. Tee was sitting there, fingering her necklace thoughtfully while gazing out over the landscape of green hills rolling past the carriage window.

WITHIN THE BROKEN BOX

The visions – as vivid as they were – lasted for only a moment and then they found themselves once more huddled around the box.

Lying within the box there was a small codex with pages of thick vellum and covers of banded, blackened adamantine.

With an air of exhaustion, Tee pulled the key out of the box. Ranthir eagerly scooped up the book. As he flipped through the book (discovering it to be written entirely in dwarven), Agnarr was playing with the lid of the box – opening and closing it, only to find that it could not be resealed.

None among them were familiar with dwarven characters, but Ranthir was hardly going to let that stand in their way now: With a wave of his hand he began to translate the text…

CODEX OF THE SHARD

(written in Dwarven)

A study of the Great Crystal, recovered from the ruins of Ibbok Turren in the 943rd Year of the Great Thane.

These are the first words in a small codex with pages of thick vellum and covers of banded, blackened adamantine. The rest of the book is dedicated to a meticulous study of a small crystalline jewel. It is written in several distinct hands.

The jewel registers with an overwhelming magical aura, thwarting more mundane efforts at identifying its properties… while simultaneously deepening the evident curiosity of the writers.

- Various efforts aimed at creating “elemental sympathies”, “energetic repercussions”, and “lesser effect echoes” meet with failure. But dozens of pages are dedicated to each experiment.

- The experimenters then turn their attentions to divination magicks. These meet with unexpected reactions. Weaker divination spells seem more powerful in the presence of the crystal, but reveal nothing of the crystal itself – the term “reflection” is often used to describe the failure, although even the writer seems hazy on what exactly that means.

- When more powerful divination spells are attempted, the casters are apparently driven mad. Despite this, the effort is attempted three times.

- The third caster is referred to by name: Sulaemesh. Like the others Sulaemesh is driven mad, but apparently his madness takes the form of scrawling or screaming the same phrases over and over again: “The Tower of the Dragon. The Lake of Silt and Ash. The City Fractured. The Stone Broken. The Net of Black Iron. The End of All Dreams.”

- At this point, it appears that the writers stop studying the crystal directly and focus their attention on trying to decipher the Vision of Sulaemesh. Many elaborate theories are concocted, but it is clear that they are mostly leading to frustration.

A period of several years appears to pass with little or no activity in the Codex. Then there is a new entry in a fresh hand, beginning with:

The crystal matches, in all respects, the properties of the dreaming shard.

The next several pages are a collation of research apparently drawn from several different sources. The dreaming shard is one small sliver of a much larger artifact known as the Dreaming Stone. The Dreaming Stone is described as “the source of all dreams” and “the resonance of the Dreaming”, among other descriptive titles.

The tone of the next several entries is one of excited discovery. But then things take a darker turn: There is a reference to “an area of great concern” and then several pages have been ripped out of the Codex. Other pages have been completely blotted out, leaving only vague references to a “Great Crypt” and “—if the shard were to awaken—“

The last few pages of the Codex are intact. They describe the design of an impenetrable box, which the writers hope will “seal both the shard and its dangerous knowledge from the waiting world”. Two boxes are created – one for the shard and one for the Codex.

Running the Campaign: Secrets of the All-Key – Campaign Journal: Session 36C

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index