One of the key concepts of “(Re-)Running the Megadungeon” is that the goal of the adventure is not and cannot be to “clear the dungeon”. Such a goal would be as meaningless as a World War II game in which the goal was, “Kill all the Nazis.”

(I suppose, in a general sense, you actually could hold such a goal. It would be something like the ultimate instantiation of the hack ‘n slash campaign: There’s a dungeon over there. Go slash at it for awhile. The important thing, however, is that one cannot reasonably expect to achieve that goal. That’s just not going to hack it.)

The loss of this clear-cut goal is problematic because “clear the dungeon” has long since become the default tactical solution for virtually every scenario in D&D. Oh, it’s usually gussied up a bit. But you’d be surprised at how often everything boils down to “clear the dungeon”. For example:

- “The forces of chaos are marshaling for an assault on the last bastion of civilization?” “How do we stop it?” “Go to the Caves of Chaos and… clear the dungeon.” (B2 Keep on the Borderlands)

- “The corrupt mayor is planning to release the Yellow Sign and drive Freeport into madness!” “How do we stop it?” “Go to the Lighthouse and… clear the dungeon.” (Freeport Trilogy)

- “Slavers are kidnapping people off the streets!” “How do we stop them?” “Go to the slave pits and… clear the dungeon.” (Scourge of the Slave Lords)

- “The Giants are arming for war!” “How do we stop them?” “Go to their steading and… clear the dungeon.” (Against the Giants)

- “Kalarel is trying to summon something terrible from the Shadowfell!” “How do we stop him?” “Go to the Keep and… clear the dungeon.” (Keep on the Shadowfell)

There’s nothing terribly wrong with this formula, of course. As you can see, it can be easily mapped to any number of potential crises. It has the virtue of being easy to set-up (Bad Guys X are trying to do Bad Thing Y and they can be found at Bad Place Z). And the players generally know exactly what they’re supposed to be doing (“Wipe them out, all of them”).

However, it does have the rather unfortunate side-effect of inherently funneling everything through the combat system, drastically narrowing the range of potential gameplay. And when you attempt to apply this default formula to the megadungeon it creates two major problems:

First, it’s a grind. If your goal is to “wipe out all the bad guys” in a dungeon filled with bad guys, then the megadungeon boils down to a very simplistic dynamic: You go into the dungeon, empty as many rooms as possible, and then retreat. Then you go back and you do it again. And again. And again. And again.

Second, the formula is inherently designed to use up material, whereas your goal with the megadungeon is recycle, reuse, and remix material. And the more you restock the dungeon while your players are trying to destock it, the more of a grind the whole thing becomes.

SETTING A DEFAULT

Having set aside the default mode of “clear the dungeon”, what are we to replace it with?

It’s not unusual at this juncture for someone to say, “Exploration.” Go poke around in the corners of the dungeon because you’re curious about what might be hanging out down there.

It’s not a bad suggestion, per se. But in my experience, exploration for the sake of exploration can be rather aimless. It lacks the necessary specificity to function as the driving force behind a campaign. I suspect this is because it doesn’t provide a strong enough criteria for decision-making: If you’re standing at an intersection in the dungeon and your goal is merely “to explore”, does it really matter which way you go? Not really. You’ll be exploring whichever way you go.

But “exploration” remains a compelling concept. Is there a way we can make it a more clearly defined goal?

Gold.

Here I once again find myself looking back to the earliest versions of the game, when the default method of play was not “kill the monsters”, but instead “find the treasure” — i.e., exploration geared towards a more specific end. And, notably, a specific end which — unlike “kill the monsters” — doesn’t pre-suppose the tactical and strategic means of success. (“Kill the monsters” implies blasting them with spells and poking them with pointy bits of metal. “Find the treasure” might mean killing monsters… but it could also mean sneaking past them, negotiating with them, distracting them, hiring them, tricking them, trading with them, or any number of other possibilities.)

TREASURE HUNTING

“Find the treasure”, in its most generic form, may not be terribly compelling. But it is sufficient for reliably getting the PCs to the entrance of the dungeon (and universal enough that it provides little meaningful constriction in terms of the types of characters that can be created; of course, there’s also no reason why a player couldn’t find a more unique goal for their PC).

Before one simply writes off “find the treasure” as bland pablum, however, consider that in its more specific forms “find the treasure” has served as the basis for some of the great stories of our time (or any time): Raiders of the Lost Ark, The Maltese Falcon, The Hobbit, The Illiad, The Golden Fleece. They’re all stories about treasure-hunting.

And OD&D builds a method for building towards that specificity right into its rules for procedural content generation: Treasure maps.

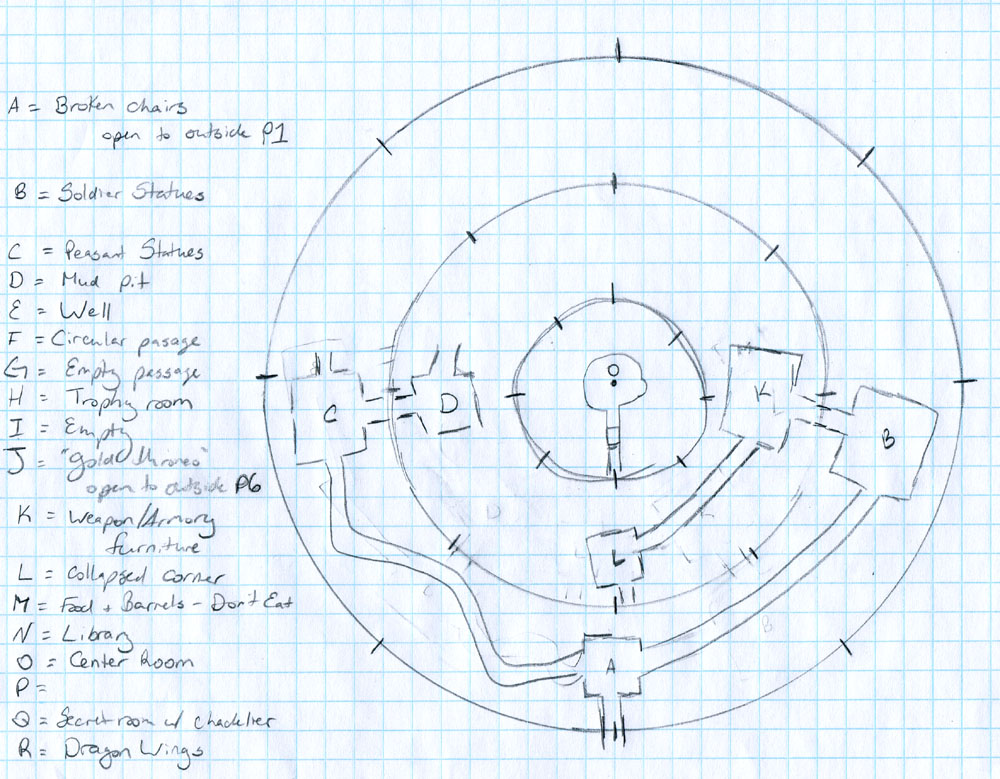

If you’re randomly generating treasure troves using the OD&D guidelines, then most intelligent foes will have a 10-15% chance of having one or more treasure maps. These can, of course, take many forms. (The Judges Guild Book of Treasure Maps supplements included everything from journal entries to scribbled notes to careful exemplars of cartography.) But the point is that a treasure map points you towards some specific treasure: You are no longer just poking around for gold in the general sense; you are specifically seeking for “the Tombe of Aerthering who is called DAMNED” (to take one example).

SPECIFIC DUNGEON GOALS

Moving beyond that, the point of setting a default goal (like “find the treasure”) is not to limit the game, but rather to provide a baseline to ensure that gaming happens. The point isn’t to say “you will go treasure-hunting”, but rather to say “if you can’t think of anything better to do, we’ll default to treasure-hunting”.

More generally, once you’ve used your default goal(s) to get the PCs into the dungeon complex, more specific goals will generally tend to accumulate on their own. In my Caverns of Thracia game, for example, a deep grudge quickly settled in against the minotaur who kept cropping up on an irregular basis. (He had killed or maimed more than a dozen PCs, so the grudge is probably understandable.) There were cheers at the table when he was finally cornered and killed in a recent session.

Have we arrived back at “killing the bad guy” as a viable megadungeon goal? Sure. (You didn’t think I was advocating for combat to be taken out of D&D, did you?) It’s not necessary to completely abandon the “there are bad guys, go get ’em” formula. But it may require a little more subtlety than that mail-order course on strategy from Palpatine University might suggest. “Wipe them out, all of them” might cut it if they’re the only guys in the neighborhood, but picking a fight with every humanoid tribe in the region because you want to put the cultists on level 4 out of commission probably isn’t a great idea.

Which begins to move us in the general direction of a more general precept: While it is necessary to maintain some sense of mystery regarding the depths of the megadungeon (as drawing back that veil of ignorance is one of the rewards for playing in a properly compelling megadungeon), it’s also important to foreshadow those depths by revealing certain details. These details, in turn, become goals for the PCs to achieve.

(The methods by which this foreshadowing can occur are essentially limitless: For example, the PCs may know that Black Donagal fled into the depths because they saw him do it. They may learn about the minotaur court by questioning a prisoner. They may find a map indicating the location of the Hall of Golden Maidens (if only they could identify one of the landmarks on their map). And so forth, not to mention divinations and magical visions.)

At this point, we can successfully return to the idea of “exploration” as a meaningful goal. Because while “exploring for the sake of exploring” is unfocused, exploring because you want to find the Tunnel of Black Rainbows is more than specific enough.

But we don’t have to stop there: The features of a megadungeon are people, places, and things. And all of these features can be foreshadowed and, thus, become goals. And out of people, places, and things every story in the history of the world has been told.

The default gets them playing. But once they start playing, there’s no limit to the things they can find or the goals they can discover.