Last week I talked about the early history of religion in D&D, and how this discordant mélange of influences eventually led to a weirdly incoherent metaphysics in which:

- Gods are arranged into pantheons, a word literally derived from the Greek name for a temple which worshipped all gods, and yet…

- People (including the clergy) almost universally choose just ONE god to worship because…

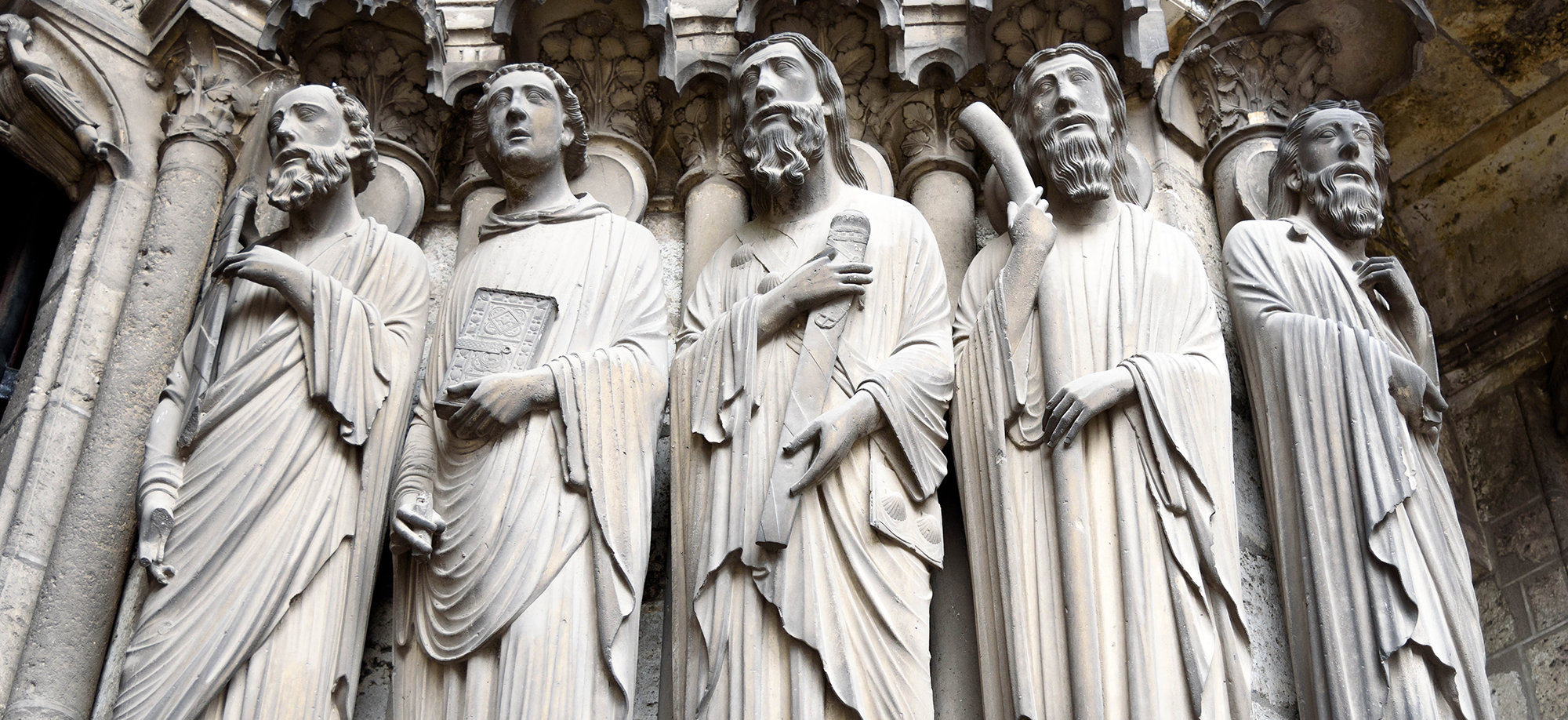

- Every civilized god gets slotted into a church based on monotheistic Christian rites, architecture, and organization. (With “evil” gods being slightly more likely to get primitive fanes and the like.)

As we look across the vast landscape of roleplaying games in the modern world, of course, we can see that any number of efforts have been made, many based on real world mythologies, to break fantasy religions out of this box. But if we’re being honest with ourselves, we can also see that D&D’s religions, by default, remain heavily influenced by contemporary Christianity (probably because that’s most of the audience’s only practical exposure to religion): Monotheistic religious practices awkwardly grafted onto a pantheistic mythology.

And this tends to bleed over into other fantasy religions and our own worldbuilding.

FAITH & BELIEF

Here’s a common, yet also complicated, example of this: In a world where gods obviously and observably exist, why do we talk about people believing or having faith in their god? If you have proof that your god exists, you don’t need to believe in them!

In large part, this paradox exists because it’s how we think about God in contemporary Christian society: We think of the divine as something you have to “believe” in, and that way of thinking just kind of elides naturally into the fantasy world. (Often without any close examination.)

But this is also why I keep talking about contemporary Christian society. Because it turns out that this is not inherently how people think about gods in the real world; the idea that the existence of God is something you need to have irrational belief in is a way of thinking that developed over time. In fact, our very understanding of the words “belief” and “faith” have been shaped by that evolution of thought.

If you look at the etymology of “belief” (from Old French) and “faith” (from Old English), you’ll discover both words originally meant basically the exact same thing: To trust someone; to have confidence in them; to be loyal to them. (The last could perhaps better be understood as a mutual exchange: You trust them, they trust you, neither of you would betray that mutual trust, and therefore you are loyal to each other; i.e., you share or keep faith with each other — a phrase which survives into modern usage while maintaining the older sense of the word.)

The meaning of the word first bled from people into ideas: To have faith or belief in a particular idea meant that you trusted it; you believed it to be true. But just writing the word “believed” is misleading to a modern sensibility, because the meaning was still fundamentally rational: You believed something was true because you had evidence for it.

What caused the meanings of the words to glide into the irrational was, in fact, their application to God. People had faith in God the same way they might have faith in their feudal lord. And obviously the Church wanted them to believe in the ideas that the Church taught them. And so “faith” and “belief” became deeply tied to the worship of God.

(“Worship” itself was a word which originally meant one who was worthy of honor, glory, renown, respect, etc. The noun was turned into a verb – i.e., to worship was to give honor, glory, renown, respect, etc. to the worshipped – and then applied to God, who was obviously worthy of those things. You can see the remnant of the original sense of “worship” in honorifics like Your Worship.)

As time passed, however, European thought became more rational – in fact, the words “rational” and “irrational” were invented, along with concordant understanding that something could only be rationally thought of as true if you had evidence that it was true.

The trick, of course, was that there was no rational evidence for the existence of God.

It took centuries, but eventually this idea became so strongly enmeshed in European thought that it was actually reflected back into the Church and inverted: Sure, there was no rational evidence for God’s existence. But you still needed to believe in God; you still needed to have faith that God’s word and his love for you were true.

At that point, through religion, “faith” and “belief” were deeply connected to something which could only be irrationally accepted as truth. Give it another century or so and these words come shooting out the other side; they’re now applied to other irrational truths that must be believed without evidence and their modern sense. In the case of “belief” the meaning remains mixed (it can apply to both rational and irrational conclusions), but when it comes to “faith” the transformation is more or less complete.

FAITH IN A WORLD OF FANTASY

So one way of understanding how the relationship between worshipers and their gods would work in a world where gods actually exist is to basically turn back the clock on our understanding of the word “faith.”

In a fantasy world, to have faith in a god doesn’t mean that you believe the god exists: It means that you are keeping faith with them. (And I think, furthermore, that it’s worth the effort to truly grok the way in which “faith” described a two-sided relationship: Not just to trust someone, but for them to also trust you. For you to be able to count on each other.)

Once you’ve made this fundamental realignment, it’s interesting to see the impact it can have on other aspects of religious thought.

For example, consider the divine right of kings. In the real world, without any actual evidence of God’s existence, a king’s position as king was essentially “evidence” that God must want them to be king. (Otherwise, of course, they wouldn’t be king.) But the whole thing gets turned on its head if gods exist and are literally endorsing temporal rulers.

- Why would a god do that? It more or less turns “god” into just another tier on the feudal hierarchy: Counts swear to dukes; dukes to kings; kings to gods. And what are the feudal duties of a god to their kings?

- How can this be compatible with multiple gods being worshipped in a kingdom? Perhaps this is the function of a pantheon? It’s more or less a committee of gods who collectively agree who’s going to be king?

- What does this do to the concept of succession? Feels like the god(s) might endorse anybody to be the next king, not just the last king’s eldest son. Does this concept “trickle down,” so that you don’t really have any inherited nobility?

- What does this mean for the hierarchy of the church? In the real world there could be a struggle between the Holy Roman Emperors and the Popes because both could argue that they were the one with divine right, but if you can literally just dial up your god and ask him that sort of thing falls apart (and, assuming your gods are, in fact, endorsing kings, the division between temporal and religious power structures seems likely to collapse or never exist in the first place).

And so forth.

On the other hand, the concept of keeping faith with someone doesn’t necessarily require a one-true-way. You can be friends with Susan in a way that’s different from being friends with Debbie, and it might be the same way with gods. (Particularly if your gods are sufficiently ineffable.) Thus, for example, in my D&D campaign world both the Imperial Church and the Reformists worship the same Nine Gods in different ways… and the Nine Gods grant spells to all of them.

CODA: ATHEISTS

On thing I rather dislike is when “atheists” show up in a fantasy world where gods verifiably exist. An atheist is someone who rejects the existence of gods because there’s no rational evidence that gods exist: If you live in a world where there IS rational evidence that gods exist and you refuse to believe that they do, that doesn’t make you an atheist. It makes you a crazy person.

In some cases, the mythology of the world is that it’s not that “atheists” don’t believe that the gods physically exist; it’s just that they don’t believe that the gods are anything other than really powerful people and/or they simply don’t pledge themselves to any god (they refuse to keep faith with any of them). But even this is a perversion of what the word “atheist” actually means and what atheists actually believe. If you want characters who reject the idea that gods are worthy of worship or faith in your fantasy world with verifiable gods, I’d recommend using a term like “heretic” or perhaps inventing a new term like “godless.”

This led to the gallows scaffold itself becoming a sign of freedom and independence. Communities, wanting to celebrate these liberties, would place the gallows in a prominent place where it could be widely viewed. This often meant the top of a hill. Thus the Puig de lees Forques (Hill of the Gallows) or the Tossal del Penjat (Hill of the Hanged Man).

This led to the gallows scaffold itself becoming a sign of freedom and independence. Communities, wanting to celebrate these liberties, would place the gallows in a prominent place where it could be widely viewed. This often meant the top of a hill. Thus the Puig de lees Forques (Hill of the Gallows) or the Tossal del Penjat (Hill of the Hanged Man).